William Blake of the Woolpack & Peacock

G. E. Bentley, Jr., (gbentley@chass.utoronto.ca) published Thomas Macklin (1752–1800), Picture-Publisher and Patron, Creator of the Macklin Bible (Mellen Press, 2016), with a section on Blake.

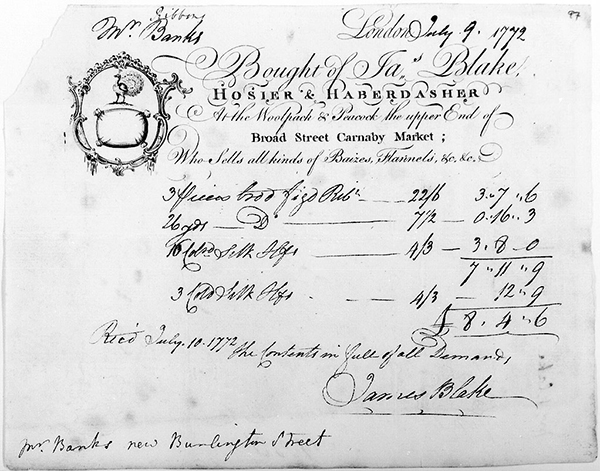

WilliamI should like to dedicate this note to Keri Davies, who tells me that the Joseph Banks invoice is dealt with on pp. 95-99 of David Jenkins-Handy, “Visual Culture and Visionary Satire: The Bodies Politic of William Blake,” Birmingham PhD, 2005. Blake was born in 1757 at the sign of the Woolpack & Peacock—or at least that was the name of his father’s haberdashery and hosiery shop at 28 Broad Street, Golden Square, in the year the poet was apprenticed, 1772. Probably there was a shop sign with an emblem of a peacock above a woolpack.

The shop title may be seen in the elegant engraved bill-head made out by James Blake, the poet’s father, to the prodigious botanist Joseph Banks. This is the only known evidence of the name of the shop.

| [Ribbons] | |||

| [M.r Banks] | London [July 9. 1772] | ||

| {emblem} | Bought of Ja.s Blake, | ||

| Hosier & Haberdasher | |||

| At the Woolpack & Peacock the upper End of | |||

| Broad Street Carnaby Market ; | |||

| Who Sells all kinds of Baizes, Flannels, &c. &c. | |||

| [3 Pieces brod figd (a) Ribn _ __ _ | 22/6 | 3..7 ..6 | |

| 26 yds ___ Do ____________ | 7½ | __ 0..16..3 | |

| 16 Colrd Silk Hfs (b) _________ | 4/3 | __ 3 . 8 ..0 | |

| 7 ..11 ..9 | |||

| 3 Cold Silk Hfs _ __ ___ | 4/3 | _ 12..9 | |

| £ 8 . 4..6 | |||

| Rec’d July. 10. 1772 the Contents in full of all Demands | |||

| James Blake | |||

| M.r Banks new Burlington Street] | |||

The portions in manuscript are given within square brackets.

(a). “figd” is “figured.”

(b). This hard-to-read word perhaps represents “Handkerchiefs.”

The Woolpack & Peacock was an uncommon name—at any rate I have found no other instance of its use—and it must have been memorable to the young poet. However, he did not make much use of the terms in his surviving writings. He does not use the word “woolpack” at all, and his references to peacocksThe Marriage of Heaven and Hell pl. 8, l. 2, Jerusalem pl. 98, l. 14, Vala p. 94, l. 51 (Night 7[b]), “Vision of the Last Judgment” (Notebook, p. 93). seem entirely conventional. Presumably the name of the shop derives from the elegance and pride of the peacock and the woolsack upon which the Lord Chancellor sits in Parliament. Banks may have chosen the shop in Broad Street at least in part because it was nearby; New Burlington Street, the address on the receipt, is just three rather circuitous streets from Broad Street.

The whole document is written in the same hand (note the formation of the capital letter “C”), though the additions to the bill of receipt and address are written a good deal more casually than the bill itself. The handwriting is the only surviving example of the handwriting of Blake’s father. It is quite distinct from that of William Blake.

The social ambition of the bill-head is more than might have been associated with the firm that sold goods wholesale to the parish workhouse. On the other hand, it seems quite appropriate for a firm selling fancy “figd Ribn” and silk handkerchiefs to the munificent Banks. Good evidence of the stock of an ambitious hosier and haberdasher is contained in an advertisement for the valuable ſtock in trade of Mrs. FRANCES JEWSON, ſole trader and millener, a bankrupt, at her houſe, No. 1, Biſhopſgate-ſtreet, [in the City. The stock included] … 1000 yards of Mecklin lace … 3000 yards of … laces; 7300 yards ditto edgings and joinings; 32,000 yards of plain and figured ribbons, … 1100 yards of ſattin luteſtring, gauze, muſlin, lawns, crape and Iriſh; 1500 yards of modes, ſarſenets and Perſians.Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser 22 Sept. 1772, for the sale of her stock by Thomas Ridgeway and Joseph Merryman. The advertisement was pointed out by Keri Davies.

The dimensions of a “piece” of cloth depend upon the material of which it is made. For muslin it was 14 ells (17.5 yards) long, for Irish linen 25 yards, for calico 28 yards, for cotton cloth 24-47 yards long by 28″ to 40″ wide, and for Hanoverian linen 128 yards.Oxford English Dictionary, “piece” sense 4a. At any rate, the quantity Banks bought was enormous. I take it that he ordered three “pieces” of broad figured ribbon the size in which it was manufactured, perhaps 36 yards, and 26 yards of tailored ribbon. The sum was enormous, the equivalent of six weeks of goods sold by James Blake, father and son, to the St. James Parish Workhouse and Schoolhouse in 1782–84 (£8.3.19).Bentley, Blake Records, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004) 36. The receipts are known only from the parish records. No other example of this bill-head, or indeed any James Blake bill-head, is known.

Perhaps William Blake was in the shop when the purchase was made—his own apprenticeship indentures were dated four weeks later, 4 August 1772. If Banks himself came, William probably did not himself wait upon such a distinguished gentleman unless his father happened not to be in the shop. If William was the salesman, he probably remembered Banks as vividly as he did Oliver Goldsmith, who may have been in Basire’s shop the same year.Bentley, Blake Records 16.

The dates of the bill (9 July 1772) and of the receipt (10 July) and Banks’s address suggest that the goods were delivered and paid for the day after they were ordered. This quantity of cloth could scarcely be carried by one man. It would have required a cart. Delivery of the goods was a heavy responsibility, requiring both strength to handle them and firmness of character to receive such a large sum of money. James Blake had four eligible sons: James (age 19), William (14), John (12), and Robert (9). James was serving his apprenticeship as a needlemaker in Southwark, and John and Robert were surely too young for such a responsibility. It seems likely that William delivered the goods and collected the money, perhaps supported by his younger brothers.

Banks had planned to accompany Captain Cook on his second circumnavigation of the world, and these fancy goods would have been appropriate as gifts to the friendly women of the South Pacific. The erotic possibilities of South Pacific voyaging were of course known to Blake. His picture of The Goats (?1799) depicts an incident in the voyage of the ship Duff to the Marquesas. Seven girls clad only in vine leaves swam out to the ship, where “some goats on board the missionary ship stripped them [the vines] off presently.”Blake, Descriptive Catalogue (1809) p. 52.

Cook wrote to Banks on 2 June 1772, I understand “I am not to have your company” because there was not room enough for Banks’s entourage of fifteen persons.Historical Records of New South Wales, vol. 1, part 1, Cook, 1762–1780, [ed. F. M. Bladen] (Sydney: Charles Potter, 1893) 357. It is puzzling that Banks was buying figured ribbons as late as 9 July. Instead of sailing to the South Pacific, Banks sailed to Iceland. One wonders what became of those twenty-six yards of figured ribbon. They were scarcely appropriate for the ice storms of Mount Hecla.Winter “Is driv’n yelling to his caves beneath mount Hecla” in “To Winter” from Poetical Sketches (1783).