“Whatever Book is for / Vengeance for Sin & / Whatever Book is Against the / Forgiveness of Sins / is not of the Father but / of Satan the Accuser / & Father of Hell”: Blake entered this comment on a sketch in which he visualized the architecture of retribution in Dante’s circles of hell. His critique of Dante’s Inferno is an expanded denunciation of “the Religion of the Enemy & Avenger” in plate 52 of Jerusalem. A bas-relief that was once erroneously attributed to Michelangelo presents Ugolino as the most striking figure in Dante’s hell, the greatest example of the violent conditions and punishments of the damned. A sensational instance of survival cannibalism, featuring a parent starved to death and reduced to eating the dead bodies of his children, the case of Ugolino exceeds the power of verbal articulation, marks the limits of form, and thus provides a testing ground for sculpture and painting in Jonathan Richardson’s account of the Science of a Connoisseur (1719).The bas-relief, which is now attributed to Pierino da Vinci, is discussed as Michelangelo’s by Jonathan Richardson, A Discourse on the Dignity, Certainty, Pleasure and Advantage, of the Science of a Connoisseur (London: Churchill, 1719) 32-35, who saw it “in the hands of Mr. Trench, a Modest, Ingenious Painter, lately arriv’d from his long Studies in Italy” (32); on its purchase by Richard Boyle, third Earl of Burlington, and its acquisition by the Devonshire collection in 1764, see Charles Avery, Studies in Italian Sculpture (London: Pindar Press, 2001) 167-90, and <http://www.artscouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/download-file/pierino_expert.pdf>, accessed 8 January 2018. Sir Joshua Reynolds’s Ugolino was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1773 and engraved in mezzotint the following year. Blake chose Ugolino as his first subject from Dante in the 1780s; he returned to him in an emblem in For Children: The Gates of Paradise (1793). Later, Blake (perhaps influenced by William Hayley) singled Ugolino out as the iconic image for Dante’s power of invention in the profile portrait he painted as part of the series of heads of the poets for Hayley’s library (c. 1800–03).On Blake’s illustrations to Dante and the visual reception of Ugolino in the eighteenth century, see Ralph Pite, The Circle of Our Vision: Dante’s Presence in English Romantic Poetry (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994) 39-67; Morton D. Paley, The Traveller in the Evening (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003) 101-07, 145-46; Antonella Braida, Dante and the Romantics (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004) 12-26, 151-78.

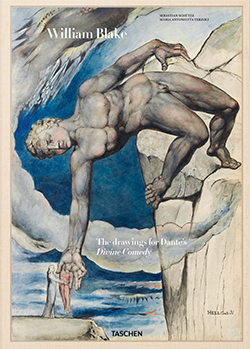

Scenes from hell occupy 72 out of the 102 designs Blake dedicated to Dante’s Commedia between 1824 and 1827. Alexander Gilchrist mentions that at the age of sixty Blake started to learn Italian in order to read Dante, which makes sense given Blake’s claim, in his marginalia to Henry Boyd’s translation of the Inferno, that “Men are hired to Run down Men of Genius under the Mask of Translators” (E 634). However, when Henry Crabb Robinson visited him in 1825, “he was making designs, or engraving …. Cary’s Dante was before him.”Alexander Gilchrist, Life of William Blake, “Pictor Ignotus,” 2 vols. (London: Macmillan, 1863) 1: 342. These were Blake’s last works, commissioned by John Linnell and left unfinished when he died. When Linnell’s collection was sold in 1918, the National Art-Collections Fund had the drawings photographed and reproduced in collotype on hand-laid paper before they were dispersed among seven collections: the Ashmolean Museum, the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, the British Museum, the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard, the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, the Royal Institution of Cornwall, and the Tate. Reproductions of the Dante watercolors were published by Albert Roe in 1953, Milton Klonsky in 1980, Corrado Gizzi in 1983, and David Bindman in 2000. Building on their work, a clothbound edition published by Taschen to mark the 750th anniversary of Dante’s birth reproduces and catalogues the drawings in codex format, with fourteen foldouts the size of the originals. The catalogue presents each plate by identifying, quoting, and translating three lines from the relevant canto and providing a generic title to sum up the subject matter, followed by indications of medium, size, and location, and a paragraph that summarizes the relevant moment in Dante’s plot, opposite a full-page or double-page-spread illustration.William Blake, Illustrations to the Divine Comedy of Dante (London: National Art-Collections Fund, 1922) follows the titles and order established in Gilchrist’s Life of Blake while correcting some discrepancies in the sale catalogue of Linnell’s collection (Christie’s, 15 March 1918). The National Art-Collections Fund sequence was followed by Albert S. Roe, Blake’s Illustrations to the Divine Comedy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1953) and Martin Butlin, The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake, 2 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981) 1: 555. Milton Klonsky’s Blake’s Dante: The Complete Illustrations to the Divine Comedy (New York: Harmony Books, 1980) rearranges the plates that were not assigned to cantos in the 1922 portfolio and places plate 100 (Male Figure Reclining) between cantos 13 and 14, plate 101 (Diagram of Hell-Circles) between cantos 10 and 12, and plate 102 (erroneously titled Female Figures Attacked by Serpents) second among the thieves sequence in canto 24. This is the sequence adopted by Corrado Gizzi in Blake e Dante (Milan: G. Mazzotta, 1983), catalogue of the exhibition held at Torre de’ Passeri, 10 September–31 October 1983. In William Blake, La divina commedia, ed. David Bindman (Paris: Bibliothèque de l’image, 2000), the thieves illustration appears in the same sequence as in Klonsky’s and Gizzi’s volumes, but Bindman does not include the plates numbered 100 and 101 in the 1922 portfolio. Klonsky reproduces relevant excerpts from J. A. Carlyle, Thomas Okey, and P. H. Wicksteed’s 1899–1901 translation, occasionally corrected with Dorothy L. Sayers’s 1949 translation; Gizzi and Bindman provide short explanations of the scenes, as does the Taschen catalogue.

The volume includes preliminary essays by the Italianist Maria Antonietta Terzoli on “Dante’s Afterworld between Classical Myth and Christian Theology” and the art historian Sebastian Schütze on Dante and Blake as masters of “visibile parlare.” The visual reception of Dante in a range of media is documented by reproductions of miniatures, initial letters, and other illustrations from fifteenth-century illuminated manuscripts, portraits of Dante from the Duomo in Florence and in Orvieto, and the topology of hell and other illustrations by Sandro Botticelli, John Flaxman, Eugène Delacroix, and Gustave Doré. From Federico Zuccari’s Dante historiato (1585–88) the volume reproduces Dante and Virgil looking at scenes of humility carved in “quaintest sculpture”Henry Francis Cary, The Vision; or Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise, 2nd ed. (London: Taylor and Hessey, 1819) 2: 86 (canto 10, line 29). in Purgatorio 10. Zuccari’s drawing translates the “stor[ies] graven on the rock” from marble bas-relief to a bidimensional composition that recalls cycles of frescoes in Renaissance palaces. These examples of “visible speaking” precede Dante’s reflections on pride, fame, and his grasp of a medieval genealogy of art, in which miniaturists are being obscured by the coming of Giotto (Purgatorio 11.73-108). Reproducing Zuccari’s representation of these scenes invites the reader to think about how the power of Dante’s invention can be translated across media for different aesthetic cultures and how these transformations are captured on paper, though no connection is made to Blake’s own illustration of the same passage. The iconography of the Commedia is also documented with sculptures, such as J.-B. Carpeaux’s Ugolino and His Children (1857–61) and Auguste Rodin’s The Gates of Hell (1880–1917); the latter elegantly marks the transition between the critical apparatus and the catalogue of Blake’s illustrations.

Schütze’s discussion of Blake’s sculptural prototypes—“Refigurations and archetypes”—is the most interesting critical contribution the volume makes to Blake studies. To translate Dante’s demons from words into images, Blake draws on sculptural prototypes, which substantiate the underground, demonic survival of classical forms. Just as Michelangelo had found in Dante the shapes of the damned, in Blake’s illustrations their compressed, contorted forms take on mannerist inflections through Michelangelo’s interpretation of classical sculptures. In the blasphemer Capaneus “writhen in proud scorn” (Inferno 14.47; Taschen plate 29; Butlin 812.27), Schütze identifies the Dying Gladiator. While this celebrated classical specimen could explain the contortion of Capaneus’s torso, the identification does not work for the arms and head of the demon. Morton Paley suggests “the reclining position of a Greek or Roman river god.”Paley, The Traveller in the Evening 133. Indeed, the headless fragment of the river god Ilissos from the Elgin Marbles offers a more immediate model for Capaneus’s torso, while the orientation of his head and limbs is closer to a monumental figure of the River Nile. Given that the annual flooding of the Nile was associated with the origin of religion, a theory that Henry Fuseli and Blake had illustrated for Erasmus Darwin’s The Botanic Garden, repurposing the form of the river god to embody the character of the blasphemous Capaneus is a powerful dialectical move. Trapping the giant into a form associated with an incipient “Net of Religion” is containment fit for a titanic energy that challenges hierarchies associated with imposing boundaries on the forces of nature. In the posture of the devil Barbariccia in the eighth circle (Inferno 21.120; Taschen plate 41; Butlin 812.39), Schütze sees the Torchbearer Ludovisi, an antique torso endowed with head and limbs by Alessandro Algardi in the early seventeenth century. This association heightens the grotesque dimension of the scene. In Dante’s demon Blake emphasizes bodily discontinuity: by exaggerating the muscular tone of the torso he declares the alterity of the arms. The classical building block fails to integrate the restored or reinvented limbs; the faulty suture disjoins the ancient from the modern in a degraded re-membering at a time when attention was focused on comparing classical copies and dissecting their restorations.

How the sculptural imagination shaped attempts to read and visualize Dante’s Commedia is a fascinating question. Seeing sculpture in the literary text is a practice that Blake encouraged, as Alexander Gourlay has observed.Alexander S. Gourlay, “‘Idolatry or Politics’: Blake’s Chaucer, the Gods of Priam, and the Powers of 1809,” Prophetic Character: Essays on William Blake in Honor of John E. Grant, ed. Gourlay (West Cornwall, CT: Locust Hill Press, 2002) 97-147. Writing about his painting Sir Jeffery Chaucer and the Nine and Twenty Pilgrims on Their Journey to Canterbury in A Descriptive Catalogue (1809), Blake invites his readers to “observe, that Chaucer makes every one of his characters perfect in his kind, every one is an Antique Statue; the image of a class, and not of an imperfect individual” (E 536). However, “these eternal principles or characters of human life” run the risk of alienation and idolatry, especially since the Greeks “have neglected to subdue the gods of Priam”: “when separated from man or humanity, who is Jesus the Saviour, the vine of eternity, they are thieves and rebels, they are destroyers.” Dante’s Inferno is the place to bring that denunciation full circle: what better way to illustrate what happens to the “human form divine” when it is separated from humanity and embodied in idols than “to incarnate and imbrute” its bright essence in the bestial forms of Dante’s demons, just as Milton’s Satan chose to take on animal forms?

Scholarship on the reception of Dante offers ways of thinking about practices of reading and viewing in the long eighteenth century, indicating how the sculptural imagination acquired on the Grand Tour might have shaped attempts to read and visualize the Commedia. Nick Havely has pointed out that Dante was common Grand Tour reading for members of the Society of Dilettanti.Nick Havely, Dante’s British Public: Readers and Texts, from the Fourteenth Century to the Present (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014) 114-27. Among them was Charles Townley, whose collection in Park Street included the Discobolus, a statue that is mentioned in Hayley’s Essay on Sculpture (1800), which Blake illustrated with an engraved head of Pericles “from a Bust in the Possession of Charles Townley.” This textual evidence explains the demonic version of the Discobolus in The Serpent Attacking Vanni Fucci (Inferno 24.97-126; Taschen plate 51; Butlin 812.48). A cast of the Dying Gladiator was on view in the Antique Room of the Royal Academy, the Ilissos at the British Museum. Since Blake did not go on the Grand Tour, arguing for such sculptural allusions opens up questions about reproduction and dissemination. Through what material mediations did such sculptures come home to British readers? How did reproductive engravings and casts shape intermedial practices? Schütze does not trace the specific routes that might have brought classical sculpture to Blake’s attention. The historical trajectories, mediations, and inflections of classical sculpture offer lines of inquiry for Blake specialists to pursue.

Comparison with the original illustrations reveals the limits of the photographic reproductions. The difference is palpable in the case of the upside-down body of Nicholas III, the Simoniac pope punished in canto 19 of the Inferno, one of the most spectacular instances of Blake’s watercolor designs. In the Taschen edition the sculptural form of the pope can be detected from the strong boundary lines and some dark touches that bring into relief the musculature of the nude, whose texture would otherwise be dissolved in the color of the background (Taschen plate 36; Butlin 812.35). Blake’s evocation of forms half perceived among trees and rocks in other illustrations could encourage us to think that this scene also experiments with the disappearance of the sculptural body as a form that is half perceived and half imagined through the medium of hell. Yet this is not what happens to the Simoniac pope in the watercolor original in the Tate collection: his body is pitch dark. Blake’s choice of a vibrant, almost-fluorescent orange for the flames of hell responds to Dante’s focus on the heightened intensity of the flames to mark out a heightened punishment for the sinner placed in the highest position, the pope (Inferno 19.33). Yet the extraordinarily vibrant oranges and blues of the watercolor are muted in the photographic reproduction; they lose their pigment, as if the photography was overexposed. At the other end of the spectrum, in the rarefied atmosphere of the eighth sphere of paradise, Dante represents the blessed as flaming spheres; the pen can hardly keep up with the imagination, so vibrant is the image (Paradiso 24.11-12, 25-27). Blake opts for a very delicate blue wash for Dante’s sphere, pink for Beatrice’s, and violet for their intersection (Taschen plate 96; Butlin 812.93). In this case, too, the loss of pigmentation occurring in photographic reproduction could have been detected by collating the photograph with the original in the Ashmolean Museum, and amended through color correction.

In a letter to Linnell in July 1826, Blake refers to “My Book of Drawings from Dante” (E 778). Gilchrist also reports that Blake sketched his Dante illustrations “in a folio volume of a hundred pages, which Mr. Linnell had given him for the purpose.”Gilchrist 1: 332. Collecting specimens dispersed across the continents is, of course, one of the missions of the Blake Archive, which tries to reproduce the experience of size and scale. The Taschen edition has chosen to follow the original size for only a portion of the illustrations, which means emphasizing some at the expense of others. The compositions that have a vertical orientation are restricted to the format of the page, whereas those with a horizontal layout extend over a whole spread or open up as foldouts to the size of Blake’s originals. As a result, readers do not need to change the orientation of the book to look at compositions that have different layouts. The volume privileges alternate acts of reading and viewing by placing the textual apparatus against each illustration, whereas placing it at the back or in a separate volume would enhance the visual narrative of the series, encouraging a practice of seeing one image after the other without textual interruptions. The key virtue of the Taschen edition is to emphasize the book aesthetic of the illustrations through the format of the codex. The reader can peruse Blake’s Dante as an object to leaf through rather than as a series of individual drawings encountered in their isolation in the study room of an archive, as specimens hanging on a gallery wall, or as a digital gallery to scroll through.