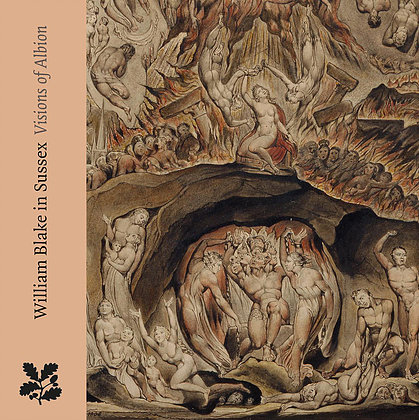

William Blake in Sussex: Visions of Albion. Petworth House (National Trust), 13 January–25 March 2018.

Andrew Loukes, ed. William Blake in Sussex: Visions of Albion. London: National Trust, in association with Paul Holberton Publishing, 2018. 120 pp. £16.50, paperback.

Luisa Calè (l.cale@bbk.ac.uk), Birkbeck, University of London, works on practices of reading, viewing, and collecting in the Romantic period. Her publications include Fuseli’s Milton Gallery: “Turning Readers into Spectators”; co-edited volumes on Dante on View: The Reception of Dante in the Visual and Performing Arts and Illustrations, Optics and Objects in Nineteenth-Century Literary and Visual Cultures; and special issues on “The Disorder of Things” (Eighteenth-Century Studies, 2011), “The Nineteenth-Century Digital Archive” (19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century, 2015), and “Literature and Sculpture at the Fin de Siècle” (Word and Image, 2018). Her current project, entitled The Book Unbound, explores practices of collecting and dismantling the book, with chapters on Walpole, Blake, and Dickens. She is also Blake’s exhibitions editor.

Landscape near Felpham (Tate, cat. no. 3, Butlin no. 368), a watercolor seascape with a boat in the bottom foreground and a ray of light illuminating William Blake’s cottage in the mid-distance, reflects Blake’s first impressions upon arrival in Felpham, Sussex, where he spent three years from 1800 to 1803: “Heaven opens here on all sides her golden Gates her windows are not obstructed by vapours.”Blake to John Flaxman, 21 September 1800, E 710, quoted in the catalogue by Hayley Flynn (64). In an earlier letter, he presented his imminent move “As the time … when Men shall again converse in Heaven & walk with Angels.”Blake to Flaxman, 12 September 1800, E 707. This promise of visionary conversation is borne out in a tail-vignette in Milton captioned “Blakes Cottage at Felpham,” featuring a scene of visitation with the virgin Ololon descending from the sky. The poem attributes the move to his prophetic character Los, so “that in three years I might write all these Visions” (Milton 36 [40].24, E 137). The importance of place is confirmed in Jerusalem: “In Felpham I heard and saw the Visions of Albion” (Jerusalem 34 [38].41, E 180). While analysis of the “Three years <Herculean> Labours at Felpham” (E 572) has focused on the composition of Milton and Jerusalem, a wider case about Blake’s visual corpus was made in William Blake in Sussex: Visions of Albion, the exhibition curated by Andrew Loukes at Petworth House from January to March 2018. It reconstructed the impact of Blake’s Felpham period by bringing together works composed in Sussex, those commissioned or acquired by the Countess and Earl of Egremont, and later works inspired by rural and maritime scenes experienced in Sussex.

Petworth’s art collection was formed in three key phases in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth centuries. Algernon Percy, tenth Earl of Northumberland (1602–68), collected Titian and was an important patron for Anthony van Dyck and Peter Lely. In the mid-1700s Charles Wyndham, second Earl of Egremont (1710–63), focused on Netherlandish paintings: Bosch, Cuyp, Hobbema, Rembrandt, and David Teniers’s Archduke Leopold’s Gallery.Christopher Hussey, “The Petworth Collection of Pictures. I,” Country Life (5 December 1925): 899-903; St. John Gore, “Old Masters at Petworth,” Studies in the History of Art 25 (1989): 121-31. George O’Brien Wyndham, third Earl of Egremont (1751–1837), added to this nucleus of Old Masters one of the most significant collections of modern paintings. Alongside portraits and landscapes, he collected narrative subjects from British history and literature, including Boydell Shakespeare Gallery paintings such as Kauffmann’s Diomed and Cressida, Northcote’s Murder of the Princes in the Tower, Reynolds’s Macbeth and the Witches and Death of Cardinal Beaufort, and Romney’s Shakespeare Nursed by Tragedy and Comedy, as well as Fuseli’s Macbeth, Banquo and the Witches, which was painted for the rival Shakespeare Gallery planned by James Woodmason.Christopher Hussey, “The Petworth Collection of Pictures. II,” Country Life (12 December 1925): 936-39; Rosie Dias, Exhibiting Englishness: John Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery and the Formation of a National Aesthetic (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013) 221. While the second earl had collected classical sculpture through Gavin Hamilton in Rome, the third acquired John Flaxman’s sculptural group of St. Michael Overcoming Satan. He is best known, however, as a patron of J. M. W. Turner.Martin Butlin, Mollie Luther, and Ian Warrell, Turner at Petworth (London: Tate Gallery, 1989); for an account of the third earl, see 105-23. His earliest Turner was Ships Bearing Up for Anchorage, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1802 in the middle of Blake’s Felpham period; Turner’s Petworth landscapes found their place below Holbein’s portrait of Henry VIII in the carved dining room in the late 1820s and 30s.Butlin et al., Turner at Petworth 18, 24-25, and fig. 16 on p. 116. While Turner would find in Petworth a second home, there is no record of Blake’s visiting during his time in Sussex.

In his catalogue essay, “‘Under a fortunate star’: The Petworth Blakes in Context,” Loukes reconstructs how the artist entered Petworth. The three Blakes hanging in the collection came through a different route, thanks to the patronage of Elizabeth Ilive, Countess of Egremont (1769–1822), whose portrait hangs in the main gallery (fig. 22 in the catalogue). She commissioned Satan Calling Up His Legions (1800–05, cat. no. 20, Butlin no. 662) and The Vision of the Last Judgment (1808, cat. no. 22, Butlin no. 642) when she was estranged from her husband. The Vision of the Last Judgment offers a gendered vision of the afterlife embodied in a feminine collective body. Blake’s composition arranges the bodies of the dead around a central opening that alludes to female genitalia, while groupings of the elect ascending to heaven in clusters of parents and children amount to a “glorification of family life.” According to Loukes, the “Figure crownd with Stars & the Moon beneath her feet with six infants around her”Blake to Ozias Humphry, 18 January 1808, E 553, quoted by Loukes (60). rising among the just, whom Blake presents as an allegory of the church, alludes to his patron, the countess, with her six surviving children, while the artist makes his own appearance as the figure bent at his work to the right. While the countess’s two Blakes were probably transferred to Petworth after her death in 1822, a third painting, The Characters in Spenser’s “Faerie Queene” (1825, cat. no. 28, Butlin no. 811), was purchased by the earl from Blake’s widow.Loukes 53. These works formed the nucleus of the exhibition, which was richly supplemented by correspondence from the Petworth archive.

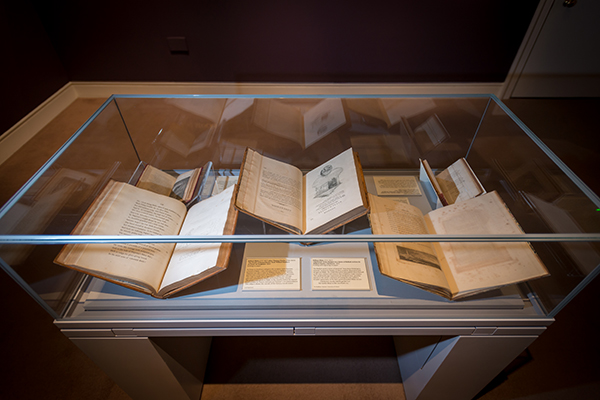

Landscape near Felpham hung next to Thomas Phillips’s 1807 portrait of Blake to introduce the exhibition, which was held in the servants’ quarters gallery situated opposite the main house, a long room divided into sections roughly corresponding to the walls. The first, “Under a fortunate star,” used Blake’s wording from the letter to Ozias Humphry in January 1808, in which he describes his design of the Last Judgment for the countess (E 552).This letter, reproduced in the catalogue (no. 23), documents the deletion of the word “Countess,” substituted by “Earl” in a different hand, suggesting that it was acquired by the earl together with The Characters in Spenser’s “Faerie Queene” from Blake’s widow. This section centered on the apocalyptic works in the Petworth collection. Lord Egremont’s copy of Robert Blair’s The Grave (1808, cat. no. 26) was open to the engraved portrait of Blake after Phillips reproduced as the frontispiece, while the awakening of the dead encircles the facing title page. This image echoes Michelangelesque groupings in The Vision of the Last Judgment and The Fall of Man (1807, V&A, cat. no. 24, Butlin no. 641), which were hung together.

An inspired curatorial choice placed the line engraving of “Chaucers Canterbury Pilgrims” (cat. no. 30) at a right angle to the watercolor of The Characters in Spenser’s “Faerie Queene.”

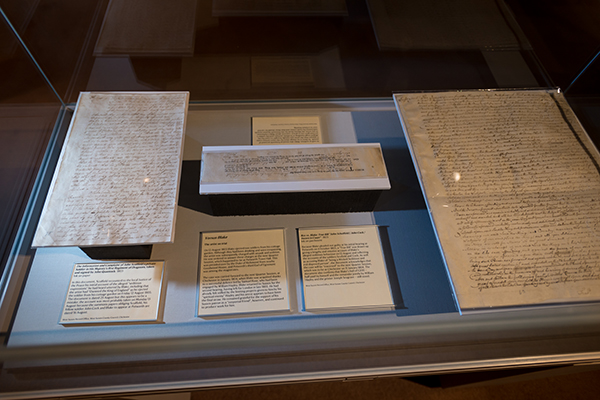

Next to Satan, a section was dedicated to relief etchings from Milton and Jerusalem under the title “Arrows of desire,” a quotation from the “Jerusalem” hymn in Milton, which encouraged viewers to situate “Englands pleasant pastures” in the land of Sussex, asking them to consider “Jerusalem builded here” (E 95). Plates from Milton also included Blake’s representation of the Felpham cottage as a site of celestial inspiration and Milton’s hitting Blake’s left foot (Milton pls. 2, 29, 36 [Bentley numbering], cat. nos. 31a-c). By contrast, the selection from Jerusalem registered the more negative spectral forms haunting the late prophetic writings. The appearance of “Hand” (Jerusalem pl. 26, cat. no. 32a) alludes to the Hunt brothers and the Examiner because of their negative review of the 1809 exhibition. “One stood forth from the Divine Family” (Jerusalem pl. 37 [Bentley numbering], cat. no. 32b) is read as Los’s attempt to rescue Albion. The plate is framed by two vignettes in which Blake explores the iconography of the recumbent figure. In the head-vignette he represents Albion in the attitude of the body of Christ as depicted in Renaissance pietàs and deposition scenes. Albion’s dangling head and arm may also recall those of the sensational female sleeper in Fuseli’s The Nightmare (1781). The catalogue entry follows Martin Myrone in identifying Fuseli’s depiction of demonic oppression as a source for the bat-shaped spectre hovering over the more static, shrouded figure of Jerusalem in the tail-vignette.Martin Myrone, Gothic Nightmares: Fuseli, Blake and the Romantic Imagination (London: Tate, 2006) 50. The entry also suggests that the theme may “have been further incited by [Blake’s] recent engraving after Maria Flaxman’s design of Serena’s bedside for Hayley’s Triumphs of Temper in 1803” (cat. no. 12). Blake’s revisionary reading of the Felpham period presents Hayley as a “spiritual enemy,” positioned as “Hyle” next to “Skofeld” (Jerusalem pl. 51, cat. no. 33), a reference to Blake’s altercation with Private John Scofield, which led to the trial for sedition documented in the vitrine opposite (cat. no. 15). This corner brilliantly mediated the transition from Blake’s infernal Miltonic views to the Virgilian pastorals on display in the next section, “On the banks of the ocean.”

“None can know the Spiritual Acts of my three years Slumber on the banks of the Ocean” (E 728), Blake wrote to Butts on 25 April 1803, “unless he has seen them in the Spirit or unless he should read My long Poem ….” The same marine coordinate returns as a starting point for visionary work in the opening of his address “To the Public” in Jerusalem: “After my three years slumber on the banks of the Ocean, I again display my Giant forms to the Public” (Jerusalem pl. 3, E 145). While in the letter the spiritual acts compensate for and exceed the world of paintings in London, which he failed to see during the three years he spent in Sussex, the section entitled “On the banks of the ocean” (later pastoral and marine subjects) used Blake’s phrase as a cue to explore the influence of Sussex on his landscape painting.

One of the big claims about the elemental imagination associated with Sussex has to do with the discovery of the sea. While Blake had represented the sea before, the exhibition brought together a corpus of seascapes shaped by empirical observation. The catalogue entry points out the “convincing rendition of wave formations” in The Spirit of God Moved upon the Face of the Waters (Abbot Hall Art Gallery, cat. no. 36, Butlin no. 690), a drawing variously related to the creation of water (Genesis 1.2) and the flood (Genesis 7.19-24), while the rainbow at the top-left corner unconvincingly suggests the covenant. Powerful waves also appear in the enigmatic Arlington Court painting (1821, cat. no. 37, Butlin no. 803), which was initially thought to be a “typical Old Testament scene,” then linked to the Odyssey and seen to be representing one or both of Odysseus’s landings on Phaeacia and Ithaca and expressing a conflict between the divine inspiration associated with the sea and the material world of classical or scientific thought associated with the land and the pagan depiction of the sun.James Lees-Milne, Diaries 1946–1949 (London: Murray, 1996) 405; Kathleen Raine, “The Sea of Time and Space,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 20.3/4 (1957): 318-37; David Bindman, Blake as an Artist (Oxford: Phaidon, 1977) 207-08. Discovered in 1949, the painting is known as The Sea of Time and Space, an expression that appears in a letter to Butts of 10 January 1803 (E 724), in the fourth Night of The Four Zoas (E 337), and three times in Milton (15 [17].39, 46, E 110; 34 [38].25, E 134), showing how the elemental world of the sea resurfaces in Blake’s prophetic imagination. Another seascape selected for the exhibition, The Angel Marking Dante with the Sevenfold “P” (1824–27, Royal Cornwall Museum, Truro, cat. no. 38, Butlin no. 812.79), represents Dante at the entrance of Mount Purgatory (Purgatorio 9.101-05). Almost all Blake’s Purgatorio illustrations set the mountain against a marine landscape,The sea also features in Blake’s illustrations to Purgatorio 1.120-28, 2.53-117, 4.16-65, 4.42-47, 5.22-62, 9.64-101, 9.101-05, 10.25-92, 10.106-27, 12.14-64, 13.20-117, 27.6-19, 27.34-42, and 27.85-109 (Butlin nos. 812.70, 72, 73, 74, 75, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, and 86). The textual references follow William Blake, La Divina Commedia, ed. David Bindman (Paris: Bibliothèque de l’image, 2000). but what makes this illustration stand out is Dante’s abject kneeling while the angel of God inscribes his brow with seven Ps, which stand for “peccata” (sins) (Purgatorio 9.112). According to the catalogue entry, this posture might reflect “Blake’s experience of William Hayley’s patronage at Felpham.” Blake registered his dislike for Dante’s architecture of retribution in a diagram of the nine circles of hell (Butlin no. 812.101). In Dante’s Purgatorio forgiveness is the outcome of a hard-won ascent to make up for the enduring weight of sin. The posture of subjection to a higher power might carry personal associations with the humiliations of social inequality and patronage. While painting the illustrations for Purgatorio, Blake might have thought of Hayley because Dante’s was among the heads of the poets that Hayley had commissioned Blake to paint for his library in Felpham. A further connection to Felpham is provided by a missed purchase. The Dante illustrations—Blake’s last great work, dated 1824–27 and left unfinished at his death—were commissioned by John Linnell, who offered them to the third Earl of Egremont. The earl declined and bought two sets of Blake’s line-engraved Illustrations of the Book of Job (1823–26, cat. no. 25) instead.

Hayley’s patronage, discussed by Mark Crosby in “‘Three years Herculean Labours at Felpham’: Blake’s Sussex Experience,” is central to the Sussex period and associated with many of the works on view, from allegorical references in Milton and Jerusalem to the big tempera portraits of the poets commissioned for his library—represented by the heads of Spenser and Milton on loan from the Manchester Art Gallery (cat. nos. 6 and 7)—and the spectacular, evanescent Urizenic form of Winter, painted in tempera on pine as part of a chimney decoration scheme for the Reverend John Johnson, a cousin of William Cowper (cat. no. 20). These were on view in a section entitled “Many admirable things.”

While Blake complained about Hayley’s commissions as “meer drudgery of business” (E 724), the biblical watercolors displayed next to The Shipwreck were works painted during the Felpham period for Butts. Displayed under the title “On the stocks” was a selection from the biblical subjects Blake listed as such in a letter to Butts:Blake to Butts, 6 July 1803 (E 729). The Three Maries at the Sepulchre (1800–03, cat. no. 19, Butlin no. 503), The Sacrifice of Jephthah’s Daughter (1803, cat. no. 17, Butlin no. 452), The Angel of the Divine Presence Clothing Adam and Eve with Coats of Skins (1803, cat. no. 16, Butlin no. 436), and Ruth the Dutiful Daughter-in-Law (1803, cat. no. 18, Butlin no. 456). As Naomi Billingsley observes in her catalogue essay, “‘On the Stocks’: Biblical Watercolours from the Felpham Period,” these works can be read as pairs: the dynamic composition of the Maries and Ruth articulates the drama of choice and response, while the more controlled, centralized symmetries of The Sacrifice of Jephthah’s Daughter and The Angel of the Divine Presence, positioned in the middle of the wall, exemplify the oppressions of institutionalized religion in a postlapsarian world in which access to the divine presence is constrained by mediation and intercession, and the odd scale of Adam and Eve exemplifies a Human Form contained and “witherd up … / By laws of sacrifice for sin” (Jerusalem 27.53-54, E 173). David Bindman has pointed out that, unlike the biblical temperas Blake had produced for Butts in 1799–1800, the Felpham watercolors are remarkable for “an astonishing radiance, which flows outward from the holy figures to pervade the whole pictorial space …, a suffusing ethereal light, transcending modelling, but leaving every form distinct and whole.”Bindman, Blake as an Artist 137. Insight into this technical development comes from the correspondence with Butts, with whom Blake shared his thinking about art, having “now given two years to the intense study of those parts of the art which relate to light & shade & colour” (E 718), as well as his ambivalent feelings about miniature, portraiture, and Hayley’s pressures toward a branch of art that would provide a livelihood.Blake to Butts, 22 November 1802, E 718; see also Bindman’s chapter on “Felpham” in Blake as an Artist (134-39).

While earlier assessments of the Felpham period have focused on its significance as a site of inspiration for his late prophetic writings rather than his visual output,“While few works of art of any importance were produced at Felpham, Blake’s mind was never more active, and his spiritual development is amply charted in his letters” (Bindman, Blake as an Artist 134). this exhibition shed light on its lasting impact on Blake’s art. Underpinned by careful reconstruction of the networks of patronage that supported Blake’s work in the 1800s, William Blake in Sussex showcased the alternative art genres supported by Hayley and Butts during his Felpham stay and the apocalyptic works for the Countess of Egremont, while the mystical Arlington Court painting and later works associated with the new sense of landscape acquired in Sussex connected the Felpham period to the works of the 1820s. The transfer of Blakes to the Petworth collection took place at a time when that “House of Art,” as John Constable described it in 1834, had become an established landmark among the British galleries of art discussed in periodicals in the run-up to the opening of the National Gallery.Constable is quoted in Butlin et al., Turner at Petworth 105. Petworth in the 1820s is captured by Turner’s 1827 interiors, showing the recent acquisition of Flaxman’s St. Michael Overcoming Satan (1826) in the north gallery (Tate, Turner Bequest CCXLIV 13) as well as Macbeth and the Witches hanging at the center of the south wall of the square dining room (Tate, Turner Bequest CCXLIV 108). Signs of changing taste are evident in George Patmore’s assessment of Reynolds’s painting as an “execrable picture,” in contrast to his praise for Cuyp—see “British Galleries of Art.—No. VII. Lord Egremont’s Gallery at Petworth,” New Monthly Magazine vol. 8, no. 31 (January 1823): 162-69 (166). Hazlitt praised Petworth for “the finest Vandykes in the world”—see William Hazlitt, “Pictures at Wilton, Stourhead, &c.,” London Magazine 8 (October 1823): 357-60 (360). However, Blake’s outsider status was captured in inventories dating to 1835 and 1838, which situate his works “upstairs in the Old Library.” None is listed in Gustav Waagen’s celebration of the Petworth collection as “one of the finest in England” in Treasures of Art in Great Britain (1854).Gustav Waagen, Treasures of Art in Great Britain: Being an Account of the Chief Collections of Paintings, Drawings, Sculptures, Illuminated MSS., &c. &c., 3 vols. (London: Murray, 1854) 3: 31-43. When Anthony Blunt rehung the house for its public opening as part of the National Trust in 1953, Blake’s three paintings were relegated to the chapel passage; they joined the core Romantic collection in the north gallery only in the 1990s.Loukes 51.