William Blake’s Universe: An Interview

with David Bindman and Esther Chadwick

Luisa Calè (l.cale@bbk.ac.uk), Birkbeck, University of London, writes about practices of reading, viewing, and collecting in the Romantic period. She is completing a monograph entitled The Book Unbound: The Material Culture of Reading and Collecting, ca. 1750–1850, with chapters on Walpole, Blake, and Dickens, funded by the Leverhulme Trust. She is the exhibitions editor for Blake.

David Bindman is emeritus professor of the History of Art, University College London. He is the author of Blake as an Artist (Phaidon, 1977) and books on Hogarth and Roubiliac. In recent years he has worked on questions of art and race. He recently published “Race is Everything”: Art and Human Difference (Reaktion Books, 2023).

Esther Chadwick is lecturer in Art History at the Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Her book, The Radical Print: Art and Politics in Late Eighteenth-Century Britain, including a chapter on Blake, will be published by the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art in spring 2024.

In this interview, the curators David Bindman and Esther Chadwick discuss the upcoming exhibition William Blake’s Universe, which opens at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (23 February–19 May) and then moves to the Hamburger Kunsthalle (14 June–8 September). The interview has been very lightly edited for style.

Can you tell us about the original idea for this exhibition?

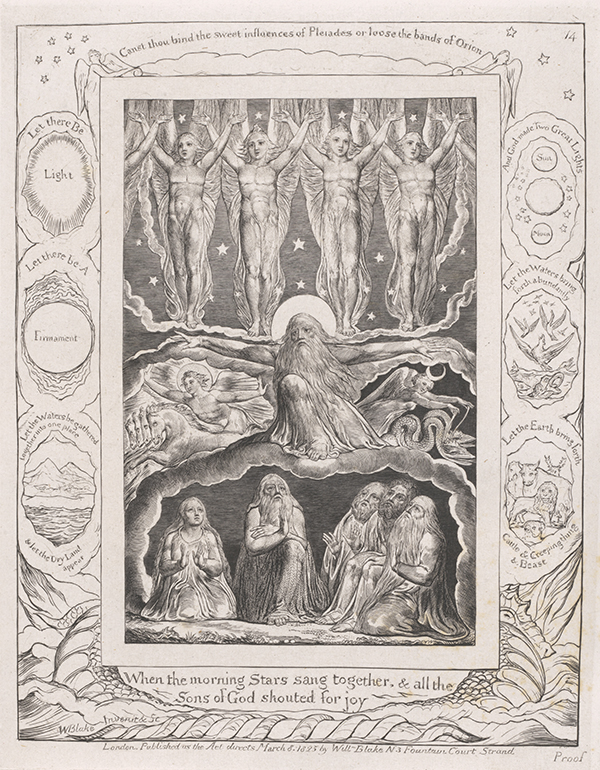

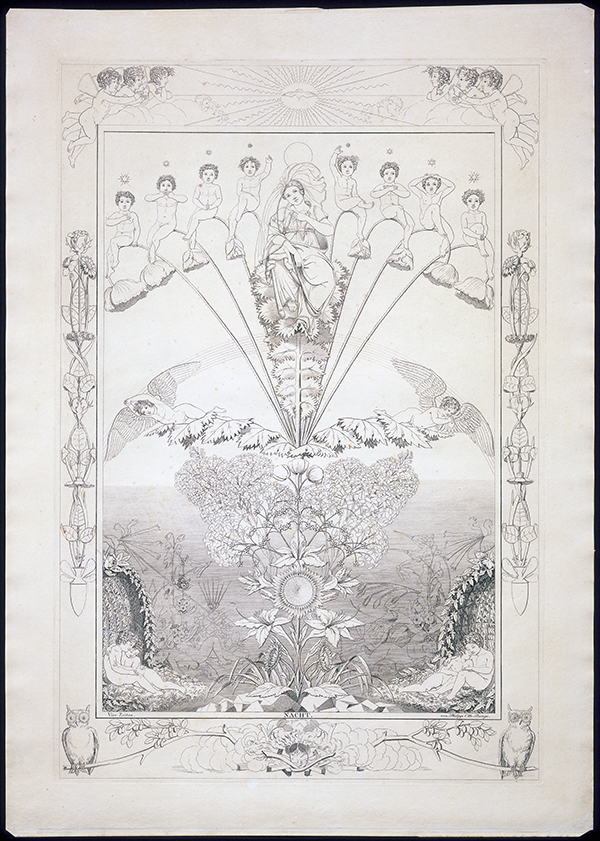

DB: The exhibition began originally as a response to Hamburg’s continuing interest in British art, which reached its high point in the 1970s with the Kunsthalle’s legendary director Werner Hofmann, who put on a series of exhibitions, Kunst um 1800, mainly on northern European art, in which he included Blake (1975), John Flaxman (1979), and Turner. At the time it was astonishingly prescient to include both Blake and Flaxman among the central artists of the Romantic era in Europe. As it happens, I was the curator of those two exhibitions, and it was an unforgettable experience. The Blake exhibition opened up the possibility of seeing Blake in a European context. Particularly intriguing was the comparison with Philipp Otto Runge, almost all of whose work is in the Kunsthalle.

EC: We felt that, by initiating a collaboration between the Fitzwilliam and the Hamburger Kunsthalle, there was an opportunity to pick up where Kunst um 1800 had left off. We were particularly intrigued by the possibilities of bringing Runge’s work to the UK, where Runge is not well known, and seeing what would happen when his work was placed in the same physical space as Blake’s. The two have often been linked in scholarship on the Romantic period, but rarely—if at all—exhibited together.

Was there an element of cultural diplomacy?

DB: Not at all in the present exhibition, but in 1975, after the entry of Britain into the European Union, the British Council had ample funds to promote British culture. Though it was never stated, I feel the choice of British artists in the series may well have been influenced by that fact. It is also the case that the idea for the present exhibition (whose original working title was Blake in Europe) came about partly as a reaction against the decision in 2016 to leave Europe.

EC: Working in collaboration with a German museum in the aftermath of the Brexit referendum seemed to give the project added significance. One could see Kunst um 1800 and Blake’s Universe as bracketing the UK’s membership of the EU, which is an interesting thought to ponder.

How is Blake redefined by the collaboration between the Hamburger Kunsthalle and the Fitzwilliam?

DB: The Fitzwilliam was the obvious partner, not only because of its superb Blake collection, but because it had only recently received the final tranche of the Geoffrey Keynes collection, including superb proof prints and the great Laocoön watercolour, which have very rarely been seen in public before. The Kunsthalle brings the definitive collection of Runge and works by Caspar David Friedrich, who are relatively little known in Britain. There is also the fascinating linkage between Blake and Runge through the journalist Henry Crabb Robinson, who essentially saw the former as possessed of the spirit of German Romanticism.

EC: Crabb Robinson’s essay on Blake appeared in the patriotic journal Vaterländisches Museum, published by Runge’s friend Friedrich Perthes, in 1811. Alas, this was too late for Runge, who had died the previous year. But what the essay shows is that contemporaries considered there to be an interest in and potential audience for Blake in Germany. This link helps us to draw out the ways in which themes of societal and spiritual regeneration, so central to Blake, were shared by other artists across Europe, and it enables Blake to be loosened from what has arguably been an overly monographic framework.

How is the exhibition structured?

DB & EC: The exhibition is divided into three parts, with an introductory section of portraits of the main artists involved. The first part is devoted to the past, Italy and antiquity, showing the common education in northern countries and Britain in the classical world; the second to the present, France and revolution, showing Blake and other artists reacting urgently to the political revolutions of their age; and the third to the future, the powerful spirituality and hope of redemption in England and Germany. This thematic presentation means we are not strictly chronological, but the final section, “The Future,” is really concerned with Blake’s work after 1800, at which point we highlight changes of emphases in his work and his varied connections to Jacob Böhme, Runge, Friedrich, and Samuel Palmer.

Does exposure to German material articulate a different kind of visionary art, compared to the millenarian public sphere discussed in Blake studies?

DB: There are obvious similarities and differences between Blake and Runge and other contemporaries. What Blake and Runge have in common is, firstly, an admiration of the seventeenth-century German mystic Jacob Böhme or Behmen, whose ideas were illustrated by the extraordinary interactive images of an eighteenth-century edition of his works, and, secondly, a deep desire to produce works that integrate all the arts in the service of Christian redemption. They are of slightly different generations (Runge died young in 1810), and they differ in their attitudes to nature; Runge was a pantheist and Blake was vocally opposed to pantheism. The ability to see the two artists side by side and in the company of Friedrich and Palmer should be a marvelous opportunity for reflection on their relationship.

EC: It’s also possible, thanks in particular to Böhme, to consider overlaps between these two spheres. Garnet Terry, the millenarian engraver to the Bank of England whose hieroglyphic print of “Daniel’s Great Image” (1793) will be on display in the central section of the exhibition, sold the works of Böhme from his bookshop in Paternoster Row, London, for example. Despite his official position at the bank, Terry easily counts as a member of London’s culture of “dangerous enthusiasm,” to borrow Jon Mee’s phrase. Runge and Friedrich have usually been framed in terms of the development of Romantic landscape painting. On the surface, that is where they most differ from Blake. Yet we’re keen to bring out the deeper commonalities, stemming from similarities in their artistic training at the royal academies in London and Copenhagen and their shared experiences of a war-torn Europe in the aftermath of the French Revolution.

Tate Britain’s William Blake exhibition in 2019–20 offered different modes of engagement with works in illuminated printing (bound books, unbound plates placed one beside the other along a wall, standing stations in the centre of the room to see both sides of pages printed recto-verso, book openings lying horizontally in glass vitrines). How will you present Blake’s books in a gallery setting?

DB & EC: There is no one way of showing the illuminated books, because some of them have been separately mounted, like America, Europe, and Jerusalem, and so will be on a wall. Working with the London-based, Hamburg-raised German designer Gitta Gschwendtner, we have devised concertina-like walls that allow the separate plates to be mounted vertically, while still retaining echoes of the book format. The Fitzwilliam copies of the illuminated books are very strongly coloured, so will have a big presence in this exhibition. Visions of the Daughters of Albion is still bound, so will be shown in a case.

Walter Benjamin contrasts the vertical format of painting with the horizontal experience of sheets of paper, books, and the acts of reading and writing.Walter Benjamin, “Painting and the Graphic Arts” (1917), trans. Rodney Livingstone, in Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media, ed. Michael W. Jennings, Brigid Doherty, and Thomas Y. Levin (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2008) 219. What considerations determine the choice to present works in horizontal or vertical displays? Is there an ethics of horizontality?

DB & EC: To be clear, curators do not necessarily have a choice, because of a museum’s conditions. The most problematic exhibits are select plates from Stedman’s Surinam, which is represented by one open volume, borrowed from Cambridge University Library, and framed illustrations of a racially offensive nature showing cruelty toward the enslaved, borrowed from the British Museum. These separate plates have to be framed (according to the rules of their lender) but still we have insisted that these objects be placed flat in a case. There is certainly an ethics of horizontality in play here. In the history of art, the vertical is associated with the honorific, and by taking these works off the wall we hope to signal a difference of approach. Still, one could argue that placing them within a display case produces problems of another nature, by making them into specimens for examination, for example. There are no easy answers. Perhaps the best way to deal with these works, short of not exhibiting them at all, is to concentrate on framing them properly through interpretative texts. Elsewhere in the exhibition, another compromise is the display of two Flaxman plaster models for church monuments, which for conservation and design reasons have to be mounted at an angle rather than placed fully vertically on a wall, as they would have been intended within a church context.

The exhibition will feature the same copy of Jerusalem that was displayed in Hamburg in 1975; what does it gain from the dialogue with German works?

DB & EC: We are showing a selection from the same coloured copy of Jerusalem that was shown in 1975 (on long-term loan to the Fitzwilliam from a private collection), with the addition of proof impressions of the frontispiece and plate 51 (“Vala, Hyle, and Skofeld”) from the Keynes bequest. The latter will be reunited with a closely related drawing from Hamburg, showing Vala, Hyle, and Skofeld plus an additional figure who is probably Hand, standing in for war and brutality. These Jerusalem selections will appear in the same room as engravings, painted fragments, and select preparatory drawings for Runge’s major project, the Times of Day, which he undertook from 1802 to 1810, the same period when Blake was at work on Jerusalem. We highlight shared themes of spiritual regeneration in these works, which may both be seen as the culmination of their makers’ vision for the role of art in redeeming humanity. For all their apparent differences (in style and format), both works are underpinned by an apocalyptic understanding of the world. The selection highlights the idea of Romantic nationalism, through Albion, and this is implicitly compared with the attitudes of Runge on the one hand, but also Palmer and Friedrich, examining the sacramental nature of nationalism in both England and Germany in the Napoleonic and post-Napoleonic period.

What are the implications of revisiting in 2024 the international field of art fleshed out in the Kunst um 1800 series? How does Blake’s European context in 2024 differ from the German Blake of 1975?

DB: The political landscape after Brexit is very different, but British academics are frankly appalled by its potential effects, which have been without exception negative. But it is also true that many of those who voted for it are full of regret. In 1975 the Kunst um 1800 exhibitions were not entirely unproblematic. One of Hofmann’s motives in setting up the exhibitions was to deal with Friedrich, who was then, thirty years after the end of the Second World War, still seriously tainted by his connections with German nationalism, so the range of the series was a way of taking him out of that context. This is no longer a problem, though Friedrich was undoubtedly an extreme nationalist. It will be really interesting to see the response in the UK to Runge’s art, which will be entirely new to almost everyone.

EC: There have been great strides in Blake scholarship since 1975, not least in understanding Blake in global as well as European contexts. But, as Jason Whittaker has discussed, Blake is still susceptible to comprehension in a narrowly nationalistic way, as the spokesperson for “Englands green & pleasant Land.” If Kunst um 1800 was inflected by concerns local to German politics in 1975, there is no escaping the new political landscape that informs our interest, in 2024, in the wider context of Romantic nationalism in which Blake can, at least partially, be situated. What I hope we show is that Blake’s words and images cannot be confined to any one ideological reading. By inviting dialogue with works by his German contemporaries (and by emphasizing how deeply he was informed by European art-historical and intellectual trends more broadly), we hope to open fresh avenues for thinking about the meanings of his work, both in the past and now.