A Blake Riddle: The Diagonal Pencil Inscription

in An Island in the MoonThe contents of this article were for the most part originally published in the introduction to my critical edition and translation of Blake’s An Island in the Moon (Una isla en la luna [Madrid: Cátedra, 2014] 41-48). Line numbers and quotations from An Island here follow my edition. I am grateful to the late G. E. Bentley, Jr., and Alexander Gourlay for reading this paper and for their many helpful suggestions.

Fernando Castanedo (fernando.castanedo@uah.es) teaches at the Universidad de Alcalá, Madrid.

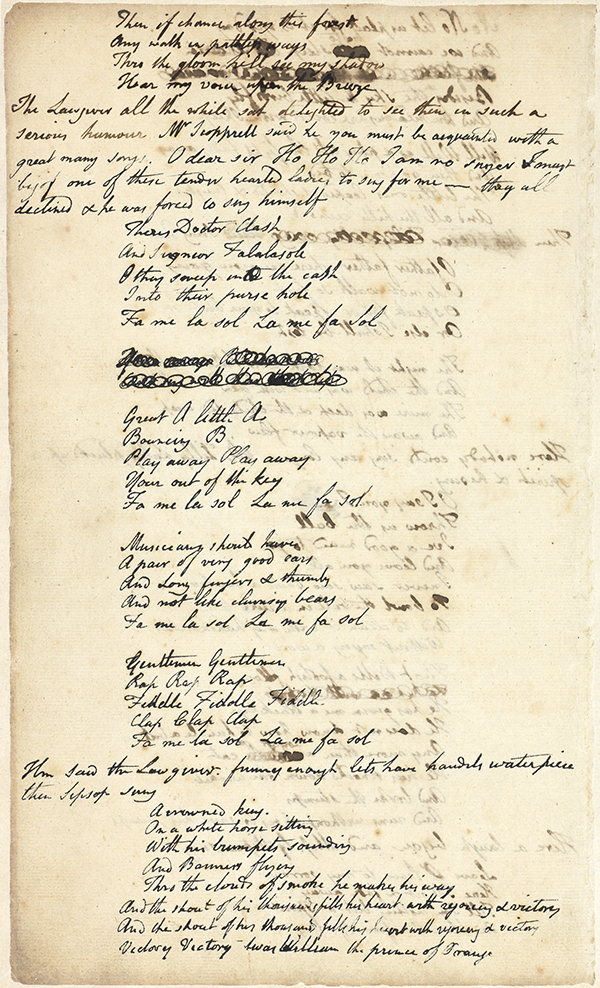

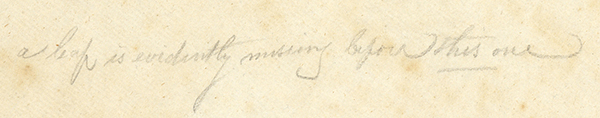

The text pages of William Blake’s manuscript An Island in the MoonThe holograph was given in 1905 to the Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge University by its owner, the painter Charles Fairfax Murray. As is well known, the title is not Blake’s, but was adapted by E. J. Ellis and W. B. Yeats from the opening words of the text (Edwin John Ellis and William Butler Yeats, eds., The Works of William Blake, Poetic, Symbolic, and Critical [London: Bernard Quaritch, 1893] 1: 187). end with a conspicuous diagonal pencil inscription: “a leaf is evidently missing before this one” (illus. 1).

While I was working on a critical edition and translation into Spanish of An Island,See note 1 above. This edition includes the diagonal pencil inscription as part of Blake’s original text. the style and content of the diagonal inscription caught my attention, and several questions arose. Who might have written it, and why anonymously? Whose authoritative voice could produce such a unanimously accepted annotation? Why had the unknown hand pronounced itself about this lacuna so confidently? Was it not somewhat bold, even for nineteenth-century standards, to qualify the absence of a leaf with “evidently”? When might this annotation have been produced? Does the handwriting bear absolutely no resemblance to Blake’s? Why did Blake leave folios 10 to 15 unused? To raise suspicions further, why do the stains on folio 9 recto seem to be mirroring quite precisely the lines on folio 8 verso and, moreover, on 8 recto? And, more generally, could the satirist who had named himself Quid the Cynic in An Island be playing a prank on his readers here, as he had done before in the text? These and other questions seemed to find reasonable answers when I considered the possibility that the line might have been written by Blake himself.

In order to see where this hypothesis might lead, as a first step I consulted a curator in manuscript paper at the Instituto del Patrimonio Cultural de España on the stains on folio 9 recto. Simultaneously, I asked an expert in handwriting identification to compare the pencil inscription with the pen-and-ink text. Both provided valuable insights. Along with other arguments, such as the satirical vein in An Island, its emphasis on the topic of literary manipulations and forgeries, the six leaves that Blake left unused in the manuscript, and its well-documented indebtedness to Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, the hypothesis might affect and perhaps enrich our understanding of Blake’s 1786 text.This is the date I propose in “On Blinks and Kisses, Monkeys and Bears: Dating William Blake’s An Island in the Moon,” Huntington Library Quarterly 80.3 (autumn 2017): 437-52.

At this point a review of the basic facts about the manuscript is in order. At the time of its donation to the Fitzwilliam Museum, it consisted of eight sheets of paper, folded and cut to form sixteen folios (leaves)—that is, thirty-two pages. While folios 2 to 8 bear identical watermarks, and 9 to 15 the corresponding countermarks, folios 1 and 16 invert this pattern, with 1 bearing the countermark and 16 the watermark.All watermarks and countermarks are identical. The watermarks bear the royal arms of England and Scotland under the early Hanoverian kings, and the countermarks present a royal cipher: a crown above the initials GR, Georgius Rex (King George). See my “Watermarks in Blake’s An Island in the Moon,” forthcoming in Blake. Blake used folios 1 to 8, recto and verso, and almost half of 9 recto, to write the text in ink. Below this half the diagonal pencil line was inscribed. Apart from several sketches and handwriting proofs (some with backwards lettering, as for copperplate engraving) on 16 verso,Folio 16 verso is titled The Lamb Lying Down with the Lion and Other Drawings, from “An Island in the Moon” Manuscript and catalogued as no. 149 in Martin Butlin, The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake, 2 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981). the remaining pages were left blank—thus, folios 9 verso, 10-15 recto and verso, and 16 recto are all unused.

Given the clear, regular pairing of watermarks and countermarks (eight of each), most editors have reasonably assumed that if the break in logic between 8 verso and 9 recto was due to an expurgation of the manuscript, then at least one folded sheet of paper (two folios or leaves—that is, four pages) must have been removed. Folio 8 verso ends with a song by Sipsop, perhaps ironically celebrating a victorious William of Orange, and 9 recto begins with a non sequitur—“them Illuminating the Manuscript”—in what seems an interrupted discourse on a new printing method that will make Blake’s alter ego, Quid, rich.For a more detailed description of the manuscript, including the inks used therein and the different writing phases, see G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Books (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977) 221-24. According to Bentley, the pages “may have been removed because they reveal too directly or too inaccurately Blake’s secret method of Illuminated Printing” (223).

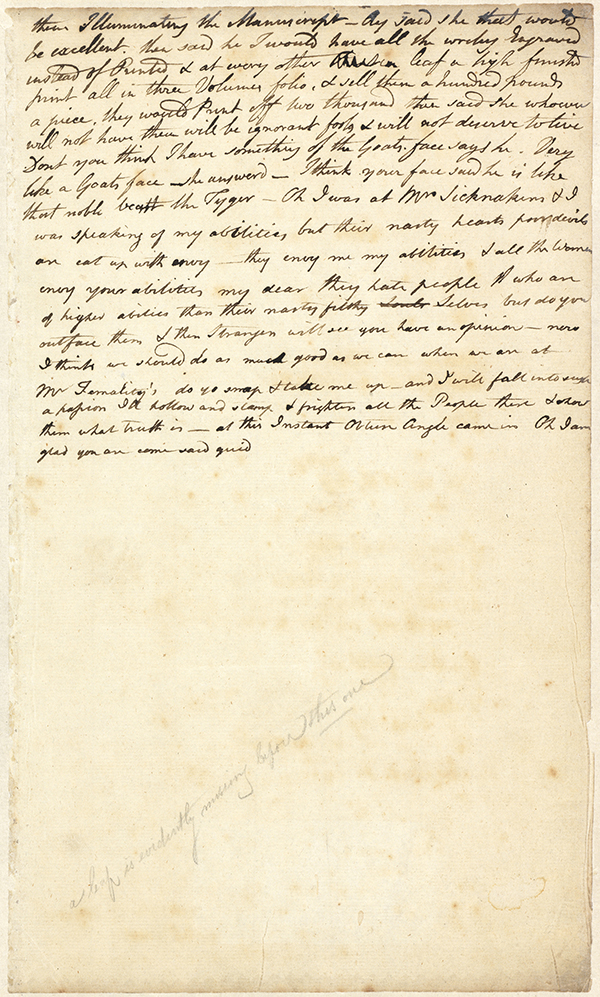

In his 1987 edition, Michael Phillips reported that he had examined folios 8 verso and 9 recto for traces of inks from the leaves that would have been lost from the center of the manuscript, with no success.Phillips 99. After proceeding likewise, I arrived at the same conclusion. Other stains could be perceived, however, on both 8 verso and 9 recto (see illus. 2 and 3).Palmer Brown already hinted at the offset on 9 recto in the early 1950s: “Am I deceived by shadows in the photograph, or is there a faint offset of some sort visible on the leaf in question, both above and below so much of the pencil notation as reads ‘A leaf is evidently’?” (letter to L. A. Holder, 13 August 1951, p. 3; correspondence in the administrative file pertaining to An Island, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge). According to paper expert María del Carmen Hidalgo Brinquis, those on 8 verso “resulted from the use of a rather porous paper and iron gall ink (especially in the deletions).”Correspondence, 14 March 2014. Thus, these stains were quite obviously produced by Blake’s writing on the other side of the same folio, 8 recto.

As for those on 9 recto, they appear to be mirroring the lines in folio 8, both verso and, more surprisingly, perhaps recto.

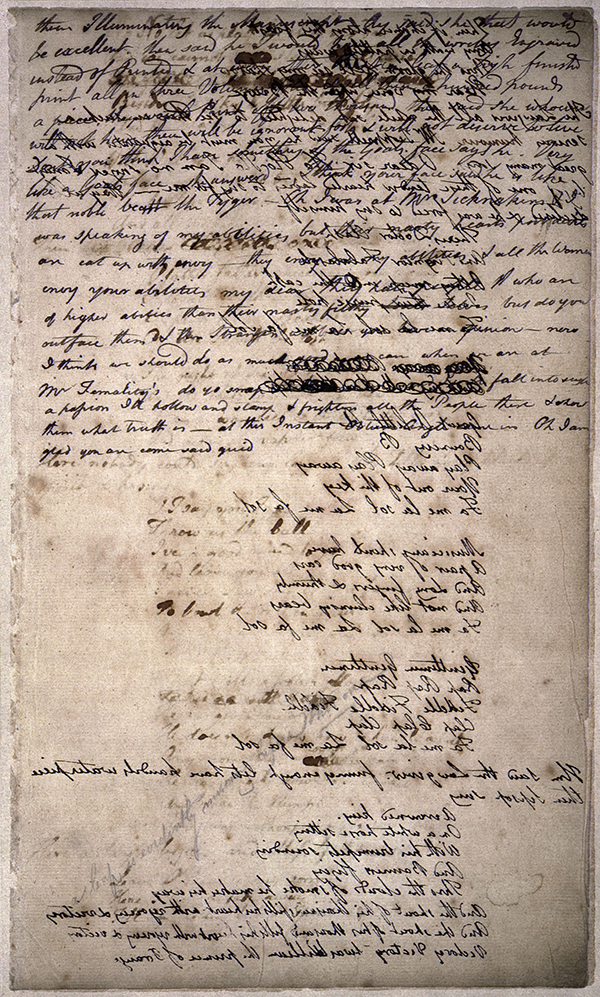

Could it be that the inks in folio 8 found their way onto a page facing it, even if at the time of writing there were two leaves between them? It might be interesting to consider one instance from each page. Line 26 in 8 recto begins with a somewhat blotched capital T, “To bowl the ball …,” which apparently has a matching stain in 9 recto. As for 8 verso, the heavily inked deletions of lines 15 and 16 seem to have a corresponding stain in 9 recto, also between lines 15 and 16. In order to determine the source of these stains—to confirm or disprove that they match the distribution of lines in folio 8, and whether they thus derive from contact with this leaf—folios 8 verso and 9 recto were digitally superimposed (illus. 4).

In view of this test, the paper curator confirmed that the stains in 9 recto proceed from contact with folio 8, both recto and verso. According to her, 8 verso and 9 recto must have been facing each other for a very long period of time, and the offset would most probably have appeared “a short time after the writing took place, through pressured contact if the manuscript remained in a humid place.”Correspondence, 12 March 2014. Finally, this outcome would have been less likely to occur had there been two leaves between them at the time when Blake was writing An Island.In 1951 Palmer Brown contacted paper expert Herbert C. Schultz, who was of the same opinion: “Exceptional pressure and moisture in the presence of susceptible ink fairly soon after writing could produce offset in a few days or weeks, while under contrary conditions no offset would occur over centuries” (P. Brown to L. A. Holder, 13 August 1951, p. 3; correspondence in the administrative file pertaining to An Island, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge). Alexander Gourlay, on the other hand, pointed out to me that “an offset could occur at any time that the pages were in contact, even long after the writing occurred, if a component of the ink was sufficiently diffusible or hygroscopic or the paper became even slightly humidified for even a few minutes” (correspondence, 10 August 2016).

Thus, given that no traces of inks from previously extracted leaves have been found, and considering how stains and writing match in the digital overlay of these two folios, would it seem reasonable to conclude that the removed pages might never have existed? Additionally, there is the oddity that what was expunged would have been one folded sheet (two folios) precisely in the center of the quire. Did the contents that Blake—or the expurgator—wish to remove happen to be just there by chance? These and other objections inevitably arose after each fresh speculation on the possible contents of the missing leaves.

However, if Blake had written the pencil inscription in accordance with the satirical vein of An Island, both the break in logic between folios 8 and 9 and the mysterious leaves in between might be accounted for. The next step was to analyze the hand that produced the inscription, comparing it to Blake’s own. As is well known, the question of Blake’s script is a difficult and vexed one. In Alexander Gourlay’s words, “Identifying Blake’s handwriting … is very hard … because [his] hand is so protean—he had a very distinctive casual hand but he also had a huge repertoire of more formal hands.”Correspondence, 31 October 2014. The text of An Island would be an instance of his casual writing, whereas the inscription might perhaps be closer to one of his formal scripts—if it is indeed his.

An additional problem derives from the fact that the inscription seems to have been written forcibly, given the tilt of the line. This in turn may have resulted in a distortion of the letters and, as a consequence, of the annotator’s handwriting, according to calligrapher José Javier Simón. Be this as it may, the calligrapher proceeded to compare the inscription with the text, analyzing the samples in the following table.All images in the table and in the following paragraph are © Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. In the left-hand column are cropped words from the pencil inscription, and, to the right, words written in ink from An Island.

| WORDS | DIAGONAL PENCIL INSCRIPTION | AN ISLAND IN THE MOON (text in ink) |

|---|---|---|

| a |  |  9 recto, line 3 9 recto, line 3 4 recto, line 35 4 recto, line 35 |

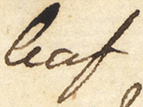

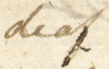

| leaf |  |  9 recto, line 3 9 recto, line 3 6 verso, line 1, “deaf” 6 verso, line 1, “deaf” 3 recto, line 10, “if” 3 recto, line 10, “if” |

| is |  |  5 recto, end of line 1 5 recto, end of line 1 5 recto, line 3 5 recto, line 3 |

| evidently* |  |  4 verso, line 1, “devils” 4 verso, line 1, “devils” 5 recto, line 33, “Lightly” 5 recto, line 33, “Lightly” 6 recto, line 39, “lightly” 6 recto, line 39, “lightly” 1 verso, line 5, “Indeed” 1 verso, line 5, “Indeed” 2 recto, line 23, “adorn’d” 2 recto, line 23, “adorn’d” |

| missing* |  |  2 verso, line 37, “ministers” 2 verso, line 37, “ministers” 2 verso, line 6, “sing” 2 verso, line 6, “sing” 8 verso, line 8, “sing” 8 verso, line 8, “sing” 3 recto, line 30, “assembly” 3 recto, line 30, “assembly” |

| before |  |  2 recto, line 38 2 recto, line 38 4 recto, line 41 4 recto, line 41 |

| this |  |  1 recto, line 18 1 recto, line 18 1 recto, line 19 1 recto, line 19 |

| one |  |  4 verso, line 21 4 verso, line 21 8 verso, line 8 8 verso, line 8 |

| * An asterisk indicates that the word in the inscription does not appear in the text of An Island. | ||

The calligrapher’s authentication report concludes that there are “several similar features, many of them unique and concurrent to the same person’s handwriting.”Simón produced his twelve-page report (“Informe pericial caligráfico”) on 4 April 2014. Translations of the quoted excerpts are mine. Firstly, he points out how the “e”s in both instances of “leaf” share a blind eye:

|  |

“leaf” (pencil inscription) |  “leaf” (9 recto, line 3) |

“is” (pencil inscription) |  “is” (5 recto, end of line 1) |

|  |

“evidently” (pencil inscription) |  “devils” (4 verso, line 1) |

|  |

“evidently” (pencil inscription) |  “lightly” (6 recto, line 39) |

|  |

“missing” (pencil inscription) |  “ministers” (2 verso, line 37) |

|  |  |

“missing” (pencil inscription) |  “sing” (8 verso, line 8) |  “sing” (2 verso, line 6) |

|  |

“before” (pencil inscription) |  “before” (2 recto, line 38) |

In view of this analysis, the calligrapher concludes that “both samples of script share a common authorship.” If Blake wrote the diagonal pencil inscription, it is relevant to consider why he produced it. Two answers seem possible: he could have been warning future readers that his holograph was incomplete, in the knowledge that he himself had been the expunger, or he might have done so in order to persuade readers of the existence of a missing portion in the manuscript—a lacuna—for the sake of playing a fairly common satirical prank.

In the first case, one might speculate how and why the expungement occurred. Perhaps all too practically, Blake simply needed some paper and, finding none at hand, took the leaves from the center of the quire.According to Phillips, “Perhaps Blake used the missing sheet or sheets from the centre for a purpose that had gained precedence, as copy drafts for etching other Songs of Innocence; or perhaps they fell victim to a later, more restrained sensibility” (21). Another possibility is that in the autumn of 1803, while anguishing over his pending trial for treason after the brawl with the soldier John Schofield in Felpham, he decided to eliminate what could become incriminating evidence, should it fall into unfriendly hands.Schuchard conjectures that the expunged pages contained “some kind of political satire. Perhaps the higher stakes of the political game, engendered by Cagliostro’s revolutionary pronouncements, persuaded Blake to destroy those pages and abandon the zany but biting comedy” (59). I am not sure that Blake considered at any time the publication of the satire, especially in view of the many abstruse and domestic references therein (see, for instance, my “‘Mr Jacko’: Prince-Riding in Blake’s An Island in the Moon,” Notes and Queries 64.1 [March 2017]: 27-29). I therefore do not see why, at this early time (Schuchard suggests that he abandoned the piece in the spring of 1786), Blake might have decided to destroy any of its pages. Venturing into conjectures such as these could lead, however, to limitless plausible suppositions that, lacking further evidence, might bring us to different impasses in our understanding of the manuscript.

On the other hand, the possibility that he was playing a literary joke would be in tune with the genre of An Island and with its indebtedness to Tristram Shandy. The intensely satirical character of the manuscript has been consistently pointed out by Blake scholars, particularly Robert F. Gleckner and Eugene Kirk.See also England (note 4 above) and Nancy Bogen, “William Blake’s Island in the Moon Revisited,” Satire Newsletter 5 (1968): 110-17. Gleckner emphasizes the extent to which Tristram Shandy stands out among the many sources Blake drew from in An Island;As Gleckner notes, “Blake mentions Sterne in two letters (to Hayley, February 23 and May 4, 1804), the latter of which suggest [sic] a clear familiarity with the novel” (319). Also worthy of note is John M. Stedmond’s early contention that “although Sterne ‘is not a Blake … An Island in the Moon is in the Sterne tradition’” (Gleckner 325n20, quoting The Comic Art of Laurence Sterne [Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1967] 101n). For echoes of Sterne’s A Sentimental Journey in Blake, see G. E. Bentley, Jr., “Sterne and Blake,” Blake 2.4 (1 April 1969): 64-65. Kirk, on the other hand, learnedly records the presence of features in Blake’s text that are characteristic of the Menippean satire.

Among these, Kirk points out the skit-like, fragmentary scenes, where ridiculed individuals indulge in banal, though purportedly brilliant, conversation. Further traits are the presence of a cynic as main character (Quid), the mocking of knowledge, science, and of the holders thereof, and an abundance of wordplay and scatological humor. All these characteristics match the classical description of the genre. Most interestingly, Kirk notes how “the lacuna or desideratum, furnished at a place of great revelation in a text, was a characteristic Menippean ruse.” He recalls how humanists, in their satires, “would impersonate some philosophus praeclarus, have him just about to reveal a stupendous mystery of learning—the secret of the philosopher’s stone, for example—and then the page would be filled with asterisks, or be missing, or suffer some accident.” Thus, “it may well be that the ‘leaf or more’ identified as missing by Erdman was left out or taken out on purpose.”Kirk 209.

While it seems unlikely that Blake would have written a leaf that he intended to leave out, the possibility that he might have purposefully created this lacuna, precisely where a money-making printing method should be described, would not be out of keeping with the spirit of An Island.Among other instances of these lacunae in early modern texts, the self-styled “second narrator” in Cervantes’s Don Quixote could not continue recording the battle between the squire from Biscay and Don Quixote: “But the trouble with all this is that, at this exact point, at these exact words, the original author of this history left the battle suspended in mid-air, excusing himself on the grounds that he himself could not find anything more written on the subject of these exploits of Don Quixote than what has already been set down” (Don Quixote 1.1.8). Perhaps the most explicit instance of how much the narrator—or Blake—enjoys playing with his readers’ expectations is found at the end of chapter 4: “Then Mr Inflammable Gass ran & shovd his head into the fire & set his hair all in a flame & ran about the room—No No he did not I was only making a fool of you.”

This is not, however, the only whimsical resource that Blake might have borrowed from another playful satirical narrator, Tristram Shandy—or Sterne—as Gleckner notes.For Gleckner, Tristram Shandy is “the most neglected of the possible satiric sources (or inspirations) for Blake” (319). Prior to this, the first known commentator on An Island, W. M. Rossetti, mentioned it as “somewhat in the Shandean vein,” before confirming to Anne Gilchrist that he also thought it rubbish (see note 6 above). Five years after Gilchrist’s letter, Swinburne similarly described it as “a sort of satire on critics and ‘philosophers,’ [that] seems to emulate the style of Sterne in his intervals of lax and dull writing” (Algernon Charles Swinburne, William Blake: A Critical Essay [London: John Camden Hotten, 1868] 183n). Traits such as the odd punctuation and the constant use of dashes, the chapters of capriciously varying lengths,Compare Tristram Shandy volume 2, chapter 13, and volume 6, chapter 15, with An Island chapter 2. the non sequiturs and cross-conversations, and the sets of characters driven by their obsessions (for example, the Battle of Namur, the influences of names, whistling, and large noses in Tristram Shandy; antiquities, experiments, philosophy, and mathematics in An Island) are present in both works. Furthermore, at times Blake seems to be inspired quite literally by Sterne, as in the emulation of Tristram’s burlesque catalogues: Our knowledge physical, metaphysical, physiological, polemical, nautical, mathematical, ænigmatical, technical, biographical, romantical, chemical, and obstetrical, with fifty other branches of it, (most of ’em ending, as these do, in ical) …. (Tristram Shandy volume 1, chapter 21)All quotations are from The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, ed. Ian Campbell Ross (1983; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988). He was the God of Physic. Painting Perspective Geometry Geography Astronomy, Cookery, Chymistry [Conjunctives] Mechanics. Tactics Pathology Phraseology Theology Mythology Astrology Osteology. Somatology in short every art & science adorn’d him as beads round his neck. (An Island chapter 3)

Blake inserts yet another humorous list in chapter 5, this time with a considerable number of mocking neologisms and deformed spellings: “I think in the first place that Chatterton was clever at Fissic Follogy, Pistinology. Arsdology, Arography. Transmography Phizography. Hogamy HAtomy.” But perhaps for the riddle posed by the diagonal pencil inscription it is unnecessary to produce an exhaustive inventory of parallels. It might suffice to observe the shared characteristics of the two narrators—how, for example, both try to endear themselves to their readers by apostrophizing them amusingly: Therefore, my dear friend and companion, if you should think me somewhat sparing of my narrative on my first setting out,—bear with me,—and let me go on, and tell my story my own way:—or if I should seem now and then to trifle upon the road,—or should sometimes put on a fool’s cap with a bell to it, for a moment or two as we pass along,—don’t fly off,—but rather courteously give me credit for a little more wisdom than appears upon my outside;—and as we jogg on, either laugh with me, or at me, or in short, do any thing,—only keep your temper. (Tristram Shandy volume 1, chapter 6) If I have not presented you with every character in the piece call me [Ass * Arse] assBlake’s ass-arse pun (or his doubts as to which word he should use) is perhaps echoing the same wordplay in Tristram Shandy volume 8, chapter 32. — (An Island chapter 2) At the end of chapter 4, previously quoted, the narrator in An Island aspires to become intimate with his readers by playing on them the joke of recanting what he has just said (“No No he did not I was only making a fool of you”). A similar event, although in the opposite sense, takes place at the end of volume 3, chapter 3, in Sterne’s novel. Instead of a narrator who makes a retraction, here we have one who, having made a mistake in describing a character’s actions, is immediately corrected by a reader who rushes into the novel (much as the diagonal annotator sneaks into An Island) and discreetly amends Tristram with a rhetorical understatement: —my uncle Toby dismounted immediately. —I did not apprehend your uncle Toby was o’ horseback.— Likewise, this narratorial playfulness that blurs the line between what is within and without the imaginary space created by the text, purposely revealing its fictional nature, is to be found in An Island: So all the people in the book enterd into the room & they could not talk any more to the present purpose. (An Island chapter 5)

Lacunae, when inserted as ruses in literary texts, work as lighthearted disrupters of the story. Sterne’s narrator includes a fair number of them in Tristram Shandy. These lacunae are graphically signaled with asterisks, and on one occasion some of the pages written by Tristram end up being used as curlers—papilliotes—by a Frenchwoman (volume 7, chapters 37-38). Whole chapters are simply left blank after the headings, although their contents are subsequently restored (volume 9, chapters 18-19). Of all the lacunae feigned by Sterne, the one that could possibly have been a direct source of inspiration for An Island’s diagonal pencil inscription is in volume 4, when the narrator jumps from chapter 23 to 25, and begins the latter:

—No doubt, Sir—there is a whole chapter wanting here—and a chasm of ten pagesAs Ross points out in a note (p. 569), Sterne’s playfulness with the peritextual elements in his novel went even further: “ten pages: In the first edition, only nine pages were in fact omitted, with the result that for the remainder of the fourth volume, the odd-numbered pages were on the verso of the leaf, the even numbers on the recto.” Blake’s indebtedness may perhaps be noted in the inconsistent numeration of An Island, if the pencil numbers scattered on some pages of the manuscript were indeed written by him (Eaves, Essick, and Viscomi consider them to be nonauthorial). made in the book by it—but the book-binder is neither a fool, or a knave, or a puppy—nor is the book a jot more imperfect, (at least upon that score)—but, on the contrary, the book is more perfect and complete by wanting the chapter, than having it, as I shall demonstrate to your reverences in this manner ….

But before I begin my demonstration, let me only tell you, that the chapter which I have torn out … was the description of my father’s, my uncle Toby’s, Trim’s and Obadiah’s setting out and journeying to the visitations at ****.

We’ll go in the coach, said my father ….

Thus Tristram proceeds to recount the contents of the “torn out” chapter 24. It seems likely that Blake would have admired here the paradox of incomplete perfection as presented by Tristram. Moreover, when compared to the classical English satirists of the eighteenth century, Sterne’s was a “dazzlingly unconventional imagination, the very kind Blake would certainly have been attracted to,” as Gleckner points out.Gleckner 321. However, if the inscription in An Island was indeed written by Blake, and if it was written with either this or another Sternian lacuna in mind, then there are at least two issues worth considering.

First, why would Blake have chosen to write his line diagonally, using a pencil instead of pen and ink and employing those rather awkward and exaggerated curlicues in, at least, “before” and “one”?Another two words might also be considered: “a” and “leaf.” According to the calligrapher, given the tilt of the inscription these curlicues would be rather unnatural marks in anyone’s handwriting. A probable answer, in due logic, is that he would have wanted to make it seem as if the inscription had not been produced by him, and thus proceeded to write it as unlike the rest of the document as possible: diagonally, in pencil,Another pencil inscription is transcribed by Eaves, Essick, and Viscomi (An Island in the Moon, object 14 [2010]). Blake wrote an “X” to the left of the initial line in the first known version of the “Nurse’s Song” from Songs of Innocence (chapter 11, folio 7 verso, line 33). As is well known, he had used these “mark[s] … of uneasiness” following Johann Caspar Lavater’s final advice in Aphorisms on Man (London: J. Johnson, 1788): “Set a mark to such [aphorisms] as left a sense of uneasiness with you” (for the use of these marks, see E 583). Thus, the “X” in An Island must have been written after the publication of Lavater’s volume, and, more interestingly, it gives us the image of the poet before his manuscript with a pencil in his hand. Could Blake have written the diagonal inscription at that sitting, with the same pencil? For the connection between this “X” in An Island and Blake’s “X” by some of Lavater’s sayings, compare the topics of childhood, play, calmness, and laughing in “Nurse’s Song” and in aphorisms 21, 54, and 226 (E 584, 585, and 588). and embellishing several words with flourishes, as opposed to the casual hand that he used in the rest of the manuscript. Considering that An Island has as one of its leitmotifs Chatterton and his Rowley fakes—alluded to in chapter 1, and explicitly mentioned in chapters 3, 5, and 7Thus Quid the Cynic—Blake’s alter ego—in chapter 7: “Chatterton never writ those poems. a parcel of fools going to Bristol—if I was to go Id find it out in a minute. but Ive found it out already—”—it would not be surprising that Blake decided to produce the (mocking) forgery of an alien inscription in his own manuscript.

On the other hand, it is also worth considering how Blake might have intended to continue his satire. Perhaps following the example of Sterne’s volume 4, chapter 24, he would have completed the break in logic between folios 8 verso and 9 recto by including (after the inscription) the contents of the “leaf” that is “evidently missing.” This he might have done with a description of the new printing method—although this would be surprising—or with some explanation as to how Quid and Mrs. Nannicantipot seem now to be living together (in chapter 7, Quid lives with Suction, possibly Robert Blake). Alternatively, he might have recounted the scene at Mr. Femality’s, announced immediately before the annotation: “when we are at Mr Femality’s do yo snap & take me up—and I will fall into such a passion Ill hollow and stamp & frighten all the People there & show them what truth is” (An Island, folio 9 recto).

Given that An Island is a far looser and more fragmentary text than Tristram Shandy, to link folios 8 verso and 9 recto by accounting for the “missing” leaves would not have been difficult. All this is rather speculative, but there is an eloquent piece of material evidence: unless Blake had it in his mind to continue writing, or, at least, had not fully dismissed that possibility, it might be reasonable to expect that he would have used the six blank leaves of paper (folios 10-15). As Bentley observes, “His poverty and his frugality directed that when he had in hand redundant stocks of paper no longer useful for their original purpose, he should carefully use them for other purposes as well.”G. E. Bentley, Jr., “The Date of Blake’s Pickering Manuscript, or, The Way of a Poet with Paper,” Studies in Bibliography 19 (1966): 232-43 (243). By “redundant stock,” Bentley is very possibly referring to a larger quantity than half a dozen leaves. However, should Blake have decided to use these for other purposes, he would have had enough paper to produce a holograph of roughly the same size as the Ballads (Pickering) Manuscript,The six unused leaves in An Island are 30.8 x 18.3 cm., and the eleven leaves (twenty-two pages) in the Ballads Manuscript are 18.4 x 12.5 cm. By folding the six leaves from An Island Blake could have obtained a twenty-four-page notebook, 18.3 x 15.4 cm. without having to trim printed pages carefully from the unsold remains of his Designs to a Series of Ballads.

In sum, both the Menippean satire and Sterne’s influence on Blake suggest how the simulated expurgation of leaves in An Island might be accounted for. Moreover, it is perhaps a simple and reasonable conjunction of all the information presently at our disposal, and clearly in tune with the spirit of the work. However, it is unlikely that this article fully explains the ruse of the “missing” leaf/leaves of paper and the diagonal pencil inscription in the manuscript. There is the enigma, for instance, of how Blake intended to proceed after writing the paragraph and the annotation in folio 9 recto, and the time at which he wrote this page is also open to debate.

Perhaps the only certainty conveyed here is that, if the hypothesis is sound, An Island ought to be taken for an unfinished manuscript, but maybe not any longer for an incomplete or expunged one. In the future, editors might wish to return to a standard numbering of the manuscript (folios 1-16) and to include the inscription as authorial. Finally, I believe that this riddle does provide a sense of Blake’s early literary workings: his devotion to humor, the playful emulation of other authors, and how in An Island he might have wished to build a larger, less fragmentary variation on the typically brief skits of the Menippean satire. After all, as Northrop Frye suggests, satire often seems to be the “real medium” of a poet who belonged to “the race of Rabelais and Apuleius.”Northrop Frye, Fearful Symmetry (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1947) 193.