“Two Newly Discovered Advertisements”:

A Response to Wayne C. Ripley

Keri Davies (keri_davies@btinternet.com) is an independent scholar whose first contribution to Blake was in vol. 27, no. 1 (summer 1993). He has written on William Blake’s parents (particularly his mother’s links to the Moravian Church) and on the social and intellectual milieu of early Blake collectors and other friends and acquaintances of the painter-poet.

In a “Minute Particular” in a recent Blake, Wayne Ripley published two examples of newspaper classified advertising from which he derived new biographical data relating to the Blake family.Wayne C. Ripley, “Two Newly Discovered Advertisements Posted by William Blake’s Father,” Blake 51.1 (summer 2017). Of course, I accept that the two advertisements that he has discovered are of genuine interest, and he has my congratulations for finding them. But the house of cards he has chosen to erect on these slight foundations is entirely mistaken. It distresses me to say so, because I think Ripley and I are working on very similar projects.

To begin with the title, “Two Newly Discovered Advertisements Posted by William Blake’s Father”; these advertisements are clearly not posted by James Blake (1722–84) but placed with newspapers by third parties for whom James Blake is providing a mailbox service. The “other” William Blake, the specialist writing engraver William Staden Blake (c. 1748–1814), supplied a postal address for half a dozen clients or more, mainly selling or renting property. A quick search of historic newspapers online yields, for example, “ANNUITIES. WANTED, two ANNUITIES,”Times (Tuesday, 24 November 1789, and Thursday, 26 November 1789). “TO be LET, a FIRST FLOOR,”Times (Wednesday, 8 August 1798). “LODGINGS—WANTED,”Times (Saturday, 22 March 1800). and “APARTMENTS, UNFURNISHED | TO be LETT,”Morning Post (Thursday, 30 October 1800). all with the contact address Blake, ’Change Alley. The common use of private names and addresses as quasi-postes restantes is obvious to anyone who carries out such a search. Coincidentally, in the 1990s the last remaining Blake residence in London, 17 South Molton Street, supplied a mailbox service from its basement, with an entrance in South Molton Lane.

Advertisers in the London daily newspapers of the day fall into two major groups: first, corporate advertisers—auctioneers, booksellers, theatres, and such—who advertise frequently and from their own premises; second, private advertisers, who use coffeehouses, inns, private houses, and shops as mailing addresses. Most of these mailing addresses, in my experience, turn up just once or twice. That there are only two known instances of James Blake advertisements is normal for this market. A third, very small, group is represented by W. S. Blake, for whom providing a mailing address seems to have been a significant part of his business.

A typical example of one-off advertising is provided by yet another William Blake (fl. 1774–90), living just around the corner from James Blake and family: H A N T S. TO be Sold by Auction, by Mr. RUSSELL, in October next, if not disposed of by private Contract, The VALUABLE MANOURS of SWANWICK and FAIRTHORNE … containing together 1700 Acres, of the yearly Value of EIGHT HUNDRED POUNDS, most desirably and advantageously situate, adjoining the Turnpike Road from Portsmouth to Southampton, and also to the Rivers of Bursledon and Kirbridge, affording easy Conveyance for the annual Fall of Timber and Wood, and of which the Estate is plentifully stocked, well preserved, and in a regular Succession. Mr. Peter Barfoot, of Cardige Common, near Botley, and adjoining the Premisses, will show the same, and Particulars may be had of William Blake, Esq. Berwicke-Street, Soho; and of Mr. Russell, at Reigate, Surrey.St. James’s Chronicle: or, British Evening-Post (4-6 September 1787). The manors being sold were part of the estate of the third Duke of Portland (1738–1809), a leading Whig politician and twice prime minister, in 1783 and again from 1807 to 1809. This presumably is the “Blake, Wm. Berwick st. Gentleman” who voted in the 1774 Westminster election.A Correct Copy of the Poll, for Electing Two Representatives in Parliament, for the City and Liberty of Westminster. Taken Oct. 11, 1774, and the Fifteen Following Days (London: Printed and sold by Cox and Bigg, 1774) 68. On 12 October 1774 the poet’s father, “James Blake Broad St Carnaby Markt Hosier & Haberdasher,” voted for Earl Percy, son of the Duke of Northumberland, and Lord Clinton.For details of the Blake family’s voting, see G. E. Bentley, Jr., William Blake and His Circle: Publications and Discoveries from 1992 <http://library.vicu.utoronto.ca/collections/special_collections/bentley_blake_collection/blake_circle/2017/William_Blake_and_His_Circle.pdf> 2816. Mr. Blake of Berwick Street shared the Blake family’s Whiggish politics, and also voted for Percy and Clinton (and not for Lord Mountmorres, Lord Mahon, or Humphry Cotes).G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004) 841, lists “William Blake, Gentleman of Berwick Street,” as voting for the Whig candidates in 1774, 1784, 1788, and 1790. No biographical data can be determined from the advertisement other than some connection between Blake of Berwick Street and the vendor or auctioneer.

Ripley first cites an advertisement in the Daily Advertiser of 23 and 24 April 1773: WANTED for a small Family, within a few Miles of London, a Maid-Servant for a Place of all Work, that can get up Linnen well, milk a Cow, and make Butter. Apply at Mr. Blake’s, Haberdasher, the End of Broad-Street, next Carnaby-Market. I do not dispute that “Mr. Blake” was James Blake, the father of William Blake, whose shop was located at 28 Broad Street, but I entirely disagree with Ripley, who seems to think that Broad Street fits the description of being “within a few Miles of London.” Broad Street is shown as well within the built-up area of the metropolis even on John Rocque’s map of London of 1746.On the development of Broad Street and environs, see “Marshall Street Area,” Survey of London, vols. 31 and 32, St. James Westminster, Part 2, ed. F. H. W. Sheppard (London: London County Council, 1963) 196-208, or British History Online <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols31-2/pt2/pp196-208>. It was within what was already termed the West End of London. Ripley stresses that the Blakes lived “outside the square mile of the City of London,” but Broad Street was no more than a mile and a quarter from Temple Bar, the western entrance to the City on Fleet Street. The advertisement makes no mention of the City, and there is no justification to narrow down in this way what is just “London” in the advertisement. The classified ad was placed by someone “within a few Miles” of London. To my mind this means somewhere like Hounslow, say, or Twickenham. It’s unlikely that Broad Street, just over a mile from the City, would have been described as within a few miles of London. This first advertisement cannot possibly refer to the Blake family’s personal circumstances.

What I find even more unacceptable is Ripley’s further assertion that “the advertisement provides evidence that the Blakes owned a cow, which they or a servant milked.” There was no common land nearby to graze cattle—the only open space was the parish burying-ground—so where did the Blakes keep their cow? In the backyard? The yard usually led to the privy and was where the washing hung to dry; it would with difficulty accommodate a cow. Or did the Blakes keep a cow in the cellar? The architectural historian Anthony Quiney describes the basement or cellar as originally “the main workrooms for the servants. There were usually at least two rooms, a kitchen and a scullery, and perhaps a number of smaller rooms for storing food, drink, crockery, cutlery and cooking implements.”Anthony Quiney, House and Home: A History of the Small English House (London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1986) 82. It was also often where a servant would sleep—the very servant that Ripley thinks the Blakes are advertising for. (The same applied later, at William Blake’s Lambeth home.)See Michael Phillips, “Reconstructing William Blake’s Lost Studio: No. 13 Hercules Buildings, Lambeth,” British Art Journal 2.1 (summer 2000): 43-48; Phillips, “No. 13 Hercules Buildings, Lambeth: William Blake’s Printmaking Workshop and Etching-Painting Studio Recovered,” British Art Journal 5.1 (spring/summer 2004): 13-21. Indeed, if Horwood’s Plan of London (1792–99) is to be trusted, and it purports to show every individual dwelling, then 28 Broad Street, the corner house on the junction with Marshall Street, did not even have a backyard.Access to Horwood’s map at high magnification is provided by <http://www.romanticlondon.org/explore-horwoods-plan>.

It’s highly unlikely that cows would be kept in a prosperous built-up area like St. James’s Parish; the parish was one of the first areas of London “to rid itself of the unpleasant environmental consequences of urban cowkeeping.”P. J. Atkins, “The Retail Milk Trade in London, c. 1790–1914,” Economic History Review ns 33.4 (November 1980): 522-37 (537). Cows were kept in backyards or cellars in slum districts, where former family homes were now in overcrowded multiple occupation. The Blakes did not live in a slum. One should also note that James Blake had a contract with St. James’s for the supply of haberdashery and hosiery to the workhouse and school.Stanley Gardner, Blake’s Innocence and Experience Retraced (London: Athlone Press; New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1986) 11. The parish overseers would not have taken kindly to cowkeeping by one of their contractors. And if the Blakes or one of their neighbors had kept a cow in cruel confinement in a cellar or yard, then surely there would have been a denunciatory couplet in “Auguries of Innocence.”

“Although there had been urban cowkeepers in London from an early date, their output was not significant in the late eighteenth century.” The milk supply came from “those producers who used the rich suburban pastures and meadows for grazing their cattle.”P. J. Atkins, “London’s Intra-Urban Milk Supply, circa 1790–1914,” “Change in the Town,” special issue, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 2.3 (1977): 383-99 (383). When Blake refers in Jerusalem to “the fields of Cows by Willans farm,” he is recalling a memorable sight from his childhood.The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman, newly rev. ed. (New York: Anchor-Random House, 1988) 172. The Willan family, ending with Thomas (1755–1828), were among the farmers who supplied the metropolis with milk; Thomas’s numerous herds of cattle comprised nearly one thousand cows.M. Brown, “‘The Fields of Cows by Willan’s Farm’: Thomas Willan of Marylebone, 1755–1828,” Westminster History Review 4 (2001): 1-5.See also Gordon E. Bannerman, Merchants and the Military in Eighteenth-Century Britain: British Army Contracts and Domestic Supply, 1739–1763 (London: Routledge, 2016). Bannerman’s chapter 6, “A Domestic Contractor: John Willan” (89-102), traces the complicated and confusing history of the Willan family as farmers and military contractors. The surveyor and agriculturist John Middleton (1751–1833) notes, “Mr. Willan’s farm, at Mary-le-bonne-park, containing upwards of 500 acres, is probably the largest in this county [Middlesex].”John Middleton, View of the Agriculture of Middlesex (London: Printed by B. Macmillan, 1798) 48. Willan’s lease expired in 1811 and the property reverted to the Crown, which used the land to create Regent’s Park.

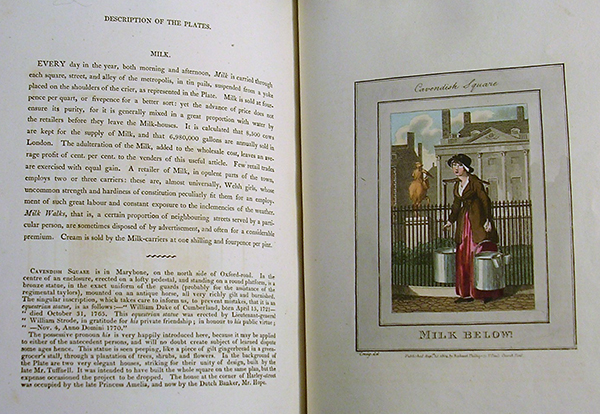

“Milk was less of a convenience food [in the late eighteenth century] than it is today, and contributed little to the average diet. Its purchase was either casual, in quantities small enough to prevent wastage caused by souring, or occasional, as part of the cream teas enjoyed by the frequenters of the pleasure gardens and resorts of peripheral London.”Atkins, “The Retail Milk Trade in London” 522. Milk was retailed round the streets of London by milkwomen, each carrying a pair of tubs holding 8 or 10 gallons (36 to 45 litres) altogether.E. H. Whetham, “The London Milk Trade, 1860–1900,” Economic History Review ns 17.2 (1964): 369-80 (369). It “was usually ladled by a measured dipper from a wide-mouthed churn into whatever containers the housewives provided.”Whetham 371. Each milkwoman had her own “walk,” a sequence of neighboring streets served by a particular person, which was “sometimes disposed of by advertisement, and often for a considerable premium.”Modern London; Being the History and Present State of the British Metropolis (London: Richard Phillips, 1804), text facing plate [43]: “MILK BELOW!—Cavendish Square.” The trade plates and their accompanying texts from this work also exist in digital form at <http://www.romanticlondon.org/ml1804-trades-map/#14/51.5114/-0.1156>. For example, from 1774: A Milk Walk to be sold. Enquire at the Fir Tree, in Church-Lane, Whitechapel; or at the King’s Arms Cellar, Southampton-Street, Strand.Daily Advertiser (Tuesday, 1 February 1774).

Middleton tells us that there were “about 8500 milch cows kept for the purpose of supplying the metropolis and its environs with milk,” each cow, on average, providing 9 quarts (more than 10 litres) a day.Middleton 333. A dairy cow thus produced much more milk than a family could have reasonably consumed. Small children were fed sops, bread soaked in milk. For everyone else milk was just a dash to color one’s tea. And how could the Blakes or any family keeping a cow dispose of the considerable surplus in the face of an entrenched street trade?

Looking again at that 1773 advertisement from the Daily Advertiser, there’s a very similar small ad in 1796 employing William Staden Blake’s address: WANTED, AS HOUSE-KEEPER and SUPERINTENDANT in a large Family, a middle-aged Widow Woman. She must have acquired, from her former situation in life, experience to conduct, with ability and address, every part of domestic arrangements; and her manners must be sufficiently polished to know how to receive and wait upon persons of the first distinction. The situation offered will be of the greatest respectability and most extensive confidence; of course very considerable talents will be looked for, and liberal terms given. Application to be made to Mr. Blake, Engraver, ’Change Alley, Cornhill.Morning Post (Monday, 29 February 1796). This may be what newspapers today would call a personal ad, but it’s in no way personal to W. S. Blake, nor was the advertisement quoted by Ripley personal to James Blake.

Ripley also cites an advertisement that appeared early in 1775 in two papers, the Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser on 18 January and the Public Advertiser on 31 January: A Middle aged Person is desirous to wait on a young Lady as Governess, understanding French and English, or to be with a Lady of Quality as Milliner, who is not inferior to any in that Talent, and whose Character can be as well recommended as her Abilities, by Persons of Quality. If this suits any Lady please to direct a Line to A. Z. at Mr. James Blake’s, Hosier, in Broad-street, Golden-square. As with the first advertisement, there is no reason to assume that it shines any light on the private life or circumstances of the Blake family. Indeed, the words “please to direct a Line to A. Z. at Mr. James Blake’s” tell us quite clearly that James Blake is offering a mailbox service. (Curiously, Ripley gives as his justification for assuming a Blake family connection with respect to this second advertisement that “there is no record of the shop’s receiving correspondence for other people,” thus ignoring the precedent set by the first advertisement he cites.)

Ripley provides us with a list of possible Blake relatives involved in the millinery or haberdashery trades. This may well prove useful some day, but is of no relevance here. He builds up a fantasy of Blake’s mother as a French-speaking milliner. As M. K. Schuchard and I have established, Catherine Wright Armitage Blake (1725–92) was a country girl from the little village of Walkeringham, Nottinghamshire.Keri Davies and Marsha Keith Schuchard, “Recovering the Lost Moravian History of William Blake’s Family,” Blake 38.1 (summer 2004): 36-43. I very much doubt if she had much opportunity to learn French there. And if not in her childhood, when? She came to London, married Thomas Armitage, and joined the Moravian congregation. After moving to London, Catherine was wife, mother, nurse (of a dying husband), active churchgoer, and shopkeeper. How would she have found the time to learn French, and to the level of fluency implied by the advertisement? Actually, the Moravians did hold language classes for their membership, but for them to learn German:

There shd be always somebody among us to learn German. Br Gottshalk will give the Brn every Day an Hour at 7 in ye Morning after ye Bible-Hour.

In general an Encouragement was giv’n to ye Brn and Srs to learn German.Moravian Church Archive and Library, London, C/36/11/3: Daily Helpers Conference Minute Book (14 February 1743–12 September 1743), n. pag. (“Monday Jul. 4th 1743”).

Catherine Armitage joined the Moravian congregation in 1750.

Between Armitage’s death and her marriage to James Blake, she had sole responsibility for the shop. Millinery may be just froufrou to some, but it takes an apprenticeship to learn it. There are many small newspaper ads of this sort:

m i l l i n e r y.

WANTED an Apprentice to a Milliner, in a pleasant and airy Part of the Town. A Premium is expected.

Further Information may be had of Mr. Edwards, Linendraper, near the Pantheon, Oxford street.Public Advertiser (Thursday, 9 April 1772).

Philippe Ariès famously called England “the birthplace of privacy.”Roger Chartier, ed., A History of Private Life, vol. 3, “Passions of the Renaissance,” trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Philippe Ariès and Georges Duby, general eds.) (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989), “Introduction,” p. 5. The eighteenth century had a great urge to privacy. For instance, William Hayley (1745–1820) was outraged that the posthumous Letters (1811) of Anna Seward (1742–1809) made mention of Elizabeth, his first wife.National Library of Scotland, Department of Manuscripts, MS 3880, fol. 190 (letter from Hayley to Sir Walter Scott, “July 16 1811”), and MS 5317, fol. 51 (letter from Scott to Hayley, “Edinr 12 Decr [1811]”). The Private Letter-Books of Sir Walter Scott, ed. Wilfred Partington (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1930), reprints Hayley’s letter with some cuts. In Richard Gough’s decades-long correspondence with George Paton (1721–1807), Gough advises Paton of his change of address but does not think it appropriate to mention the occasion—his getting married.National Library of Scotland, Department of Manuscripts, Adv. MS 29.5.6(i), fol. 55 (12 August 1774, Gough to Paton). When Francis Douce’s wife, Isabella, died in 1830, Douce (1757–1834) was not well enough to attend her burial. Not one of his friends at the interment knew the deceased’s Christian name. Isabella’s female friends, by custom, did not attend funerals. She had to be buried as simply “Douce.”The Douce Legacy: An Exhibition to Commemorate the 150th Anniversary of the Bequest of Francis Douce (1757–1834) (Oxford: Bodleian Library, 1984) 10, citing the burial register of St. Pancras churchyard, 1830, no. 950 (London Metropolitan Archives). These are just a few examples establishing that eighteenth-century obsession with privacy, which would also apply to personal ads. Classified advertisements such as those cited are always concerned to retain privacy, never giving the advertiser’s private address.

We also see this obsession with family privacy constantly at work in eighteenth-century marriages. Blake’s mother was twice married clandestinely at the Rev. Alexander Keith’s notorious Mayfair Chapel (to Thomas Armitage in 1746 and to James Blake in 1752). James Gillray’s parents and the grandparents of Percy Bysshe Shelley were wed there too.Gillray carefully preserved his parents’ marriage certificate. See British Library, Department of Manuscripts, Add. MS 27337 (Gillray family papers, 1751–1830). Fol. 2, dated “December 22d. 1751,” is the certificate, complete with five-shilling stamp. The term “clandestine marriage” bore a specific meaning in the eighteenth century, denoting a marriage celebrated before an ordained clergyman of the Church of England but without banns or license or held outside canonical hours.Rebecca Probert, Marriage Law and Practice in the Long Eighteenth Century: A Reassessment (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009) 166. It doesn’t mean that such marriages were in any way hugger-mugger or clandestine in any wider sense, but they did offer complete privacy.

A French visitor to England in the late seventeenth century, Henri Misson, claimed confidently that “to proclaim Ban[n]s is a Thing no Body now cares to have done; very few are willing to have their Affairs declar’d to all the World in a publick Place, when for a Guinea they may do it Snug, and without Noise.”Henri Misson de Valbourg, M. Misson’s Memoirs and Observations in His Travels over England. With Some Account of Scotland and Ireland. Dispos’d in Alphabetical Order. Written Originally in French, and Translated by Mr. Ozell (London: Printed for D. Browne et al., 1719) 183. Ozell’s translation is of Mémoires et observations faites par un voyageur en Angleterre, published in 1698. Misson qualifies his generalization, adding, “What I shall say here therefore is ordinarily practis’d only among those of the Church of England, and among People of a middle Condition: To which we may add, that live in or near London.”Misson 349. By the mid-eighteenth century, the practice had become widespread. According to the churchwardens of Battersea, “the reason why our marriages are so few is because of the evil practice of marrying at the Fleet in a clandestine and scandalous manner.”Quoted by Probert 192. Clandestine marriages within the environs (the “Rules”) of the Fleet Prison were even more frequent than those at the Mayfair Chapel. Lawrence Stone offers the “reasonable guess” that clandestine marriages accounted for fifteen to twenty percent of marriages, albeit based solely on marriages in London.Lawrence Stone, Road to Divorce: England, 1530–1987 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990) 115. R. B. Outhwaite, using a slightly different definition, suggests that around a quarter of marriages were clandestine.R. B. Outhwaite, Clandestine Marriage in England, 1500–1850 (London: Hambledon Press, 1995) 49.

It is worth making the point that a clandestine marriage was not necessarily a cheap option. Keith’s Mayfair Chapel charged one guinea until four p.m., and more thereafter. The Way to Mr. Keith’s Chapel is thro’ Piccadilly, by the End of St. James’s Street, and down Clarges Street, and turn on the Left Hand. The Marriages (together with a Licence on a Five Shilling Stamp, and Certificate) are carried on for a Guinea, as usual, any Time till Four in the Afternoon by another regular Clergyman, at Mr. Keith’s Little Chapel in May-Fair, near Hyde-Park-Corner, opposite the Great Chapel, and within Ten Yards of it. There is a Porch at the Door like a Country Church Porch.Penny London Post, or, the Morning Advertiser (19-22 August 1748). These same words recur as part of a repeated news item throughout August that year. Such marriages were rendered illegal by Lord Hardwicke’s Marriage Act of 1753 (“An Act for the Better Preventing of Clandestine Marriage,” 26 Geo. II. c. 33), which put a stop to the marriages at Mayfair; on 24 March 1754, the day before the Hardwicke Act came into force, sixty-one couples were married there. Outhwaite notes that Horace Walpole, outraged by Hardwicke’s Act, … [wrote] to Seymour Conway: “It is well that you are married. How would my lady A. have liked to be asked in a parish-church for three Sundays running? I really believe she would have worn her weeds forever, rather than have passed through so impudent a ceremony.” It is very reminiscent of Lydia Languish’s despair, at the collapse of her plans for elopement and a “Scotch parson,” that she might “perhaps be cried three times in a country-church and have an unmannerly fat clerk ask the consent of every butcher in the parish to join John Absolute and Lydia Languish, Spinster!”R. B. Outhwaite, “Age at Marriage in England from the Late Seventeenth to the Nineteenth Century,” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 23 (1973): 55-70 (65). The Lydia Languish reference is to R. B. Sheridan, The Rivals, act 5, scene 1.

In the longer run the Hardwicke Act may have boosted the tendency to marry by license.Outhwaite, Clandestine Marriage in England 48. William Blake and Catherine Sophia Boucher (1762–1831) got married by bishop’s license in Battersea on 18 August 1782. Like other couples in eighteenth-century marriages, they wanted no publicity from the calling of banns. That would have made what was a private family matter into something the neighbors could gossip about (and expect a cask of bridal ale to drink the health of the married couple).

To return to Ripley’s basic misunderstanding, I have already pointed out the large number of third-party advertisements involving W. S. Blake, and another, one off, for Blake of Berwick Street. Why should James Blake be the exception? Generally, advertisers avoided using their own names and addresses in personal ads, in part to avoid a queue of applicants outside their front doors, hence the innovation of the box number in the Daily Telegraph’s classified advertising in the latter half of the nineteenth century.Martin Conboy, Journalism: A Critical History (London: Sage, 2004) 121. Ripley’s error stems from disregarding the high value that the eighteenth century placed on privacy, as I have shown through examples both with the Blake family and within the Blake circle. If James Blake had wanted to place an advertisement relating to his own domestic circumstances, he would have placed it with another shop to maintain his family’s privacy. From a wider view, this means that there must be much that William Blake didn’t tell John Linnell and that Linnell didn’t tell Alexander Gilchrist. There is need for deeper delving into William Blake’s life and times, and, yes, that can mean careful searching of historic newspaper files.