Lord Tennyson’s Copy of Blake’s Illustrations of the Book of Job (1826)

Sibylle Erle (sibylle.erle@bishopg.ac.uk), FRSA, is senior lecturer in English at Bishop Grosseteste University Lincoln, author of Blake, Lavater and Physiognomy (Legenda, 2010), co-editor of Science, Technology and the Senses (special issue for RaVoN, 2008), and volume editor of Panoramas, 1787–1900: Texts and Contexts (5 vols., Pickering & Chatto, 2012). With Morton D. Paley she is now co-editing The Reception of Blake in Europe (Bloomsbury). She has co-curated the display Blake and Physiognomy (2010–11) at Tate Britain and devised an online exhibition of Tennyson’s copy of Blake’s Job for the Tennyson Research Centre (2013) <http://www.lincstothepast.com/exhibitions/tennyson/tennyson-blake-and-the-book-of-job>. Apart from reception, she is working on “character” in the romantic period.

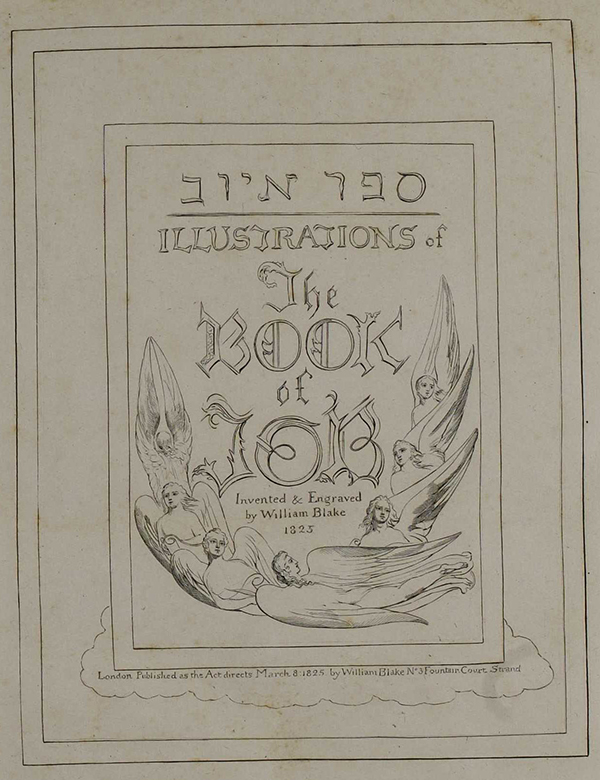

We now know not only that Alfred, Lord Tennyson, owned a copy of William Blake’s Illustrations of the Book of Job, but also that it had pride of place in his collection at Farringford on the Isle of Wight in the early 1860s. According to a list kept at the Tennyson Research Centre in Lincoln, he displayed it on his drawing-room table well before he received Alexander Gilchrist’s Life of Blake (1863) and well before the general Blake revival. His wife, Emily, recorded in her journal that Tennyson acquired Blake’s Job on 9 April 1856. It is one of the 215 published “Proof” copies (65 on French paper and 150 on India paper) printed in 1826 by James Lahee, since the word was erased after these copies had been printed. Tennyson’s copy is on India paper.The watermark J WHATMAN TURKEY MILL 1825 appears on pls. 4, 7, 8, 13, 18, and 21 (see Bentley, Blake Books p. 519, on the watermark).

The copy was, in fact, a present from Benjamin Jowett (1817–93), the Regius Professor of Greek at Oxford and a long-term friend of the Tennysons. Jowett had been introduced in 1852 in Twickenham, where Tennyson was living at the time: “He [Tennyson] came, and the poet and ‘philosopher’ were charmed with each other” (Abbott and Campbell 1: 198). After Tennyson moved to Farringford, he regularly invited Jowett to stay with him and his family over Christmas. Jowett would visit during the year as well, but stay in lodgings nearby (Abbott and Campbell 1: 339). Since he took an interest in the controversies about the Bible, Jowett had gone to Germany in the 1840s and familiarized himself with higher criticism, which laid the foundation for his The Epistles of St. Paul (1855). He acquired his copy of Job (possibly from John Linnell) before February 1845, when he is known to have shown it in Oxford to the poet and critic Francis Turner Palgrave (1824–97), who summarized his impressions in a letter to his mother: “I have seen nothing so extraordinary for a long time. Some [engravings], as of Job in misery and of the Morning Stars singing for joy, are beautiful, some, as of a man tormented by dreams and The Vision of the Night, are most awful” (quoted in Bryant 138). It was most likely this, his own copy, that Jowett decided to give to Tennyson. Jowett was attacked and persecuted because his analysis in The Epistles of St. Paul’s use of the Greek language and literary devices was considered to be heretical by his Oxford colleagues. In the introduction to his reading of the First Epistle to the Thessalonians, he outlines his radically new approach: There is a growth in the Epistles of St. Paul, it is true; but it is the growth of Christian life, not of intellectual progress,—the growth not of reflection, but of spiritual experience, enlarging as the world widens before the Apostle’s eyes, … with the changes in the Apostle’s own life, or the circumstances of his converts. (1: 3) To deny differences of thought and character in different persons, or in the same person at different times, or to deny the still greater differences of ages and states of society, renders the Scripture unmeaning, and, by depriving us of all rule of interpretation, enables us to substitute for its historical and grammatical sense any other that we please. (1: 14) Jowett may have identified with Job, who was deserted and criticized by his friends, and may have presented Blake’s Job to Tennyson as a gift of comfort because Tennyson had many hostile reviews of Maud (1855).Jowett seems to have finished his “On the Interpretation of Scripture” (1860), in which he expounds higher criticism, during a visit to the Isle of Wight. Charles LaPorte, in drawing attention to Jowett’s astute comments elsewhere on Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, notes: “It is supremely unlikely that Jowett could have missed the resemblance of the Arthurian legends to the scriptures. … By The Idylls’s practical inception in February of 1856, Tennyson had already begun to theorize and even aestheticize textual fragmentation of the sort discussed by Jowett as ‘the great historical aspect of religion’” (81).

From 1863, the year in which Gilchrist’s two-volume biography was published, interest in Blake as well as his works was rekindled. In July Anne Gilchrist sent Tennyson a copy of the Life of Blake, explaining in the accompanying letter that she was fulfilling a wish of her late husband’s:I was given permission to include this letter (letter 6802) by the Tennyson Research Centre, Lincolnshire County Council.

Earls Colne

Halstead, Essex

July 4th 1863

Dear Sir,

It was an often expressed intention of my dear Husband’s when engaged on the accompanying “Life of Blake” to send you a copy; both in token of his own feelings of earnest admiration & gratitude towards you and also not without a hope that his book might, were it only for the subject’s value, win some share of your interest & sympathy. And now that you see under what mournful circumstances the work at last issues forth perhaps this fact of its coming to you from a hand that can never again be stretched out with a gift, will deepen the interest with which you read & make you cherish a kindness for the memory of the beloved author.

I am dear Sir,

Yours very faithfully & reverently

Annie Gilchrist

Both volumes of the Life contain plates and illustrations from Blake’s works, and there are small designs or sketches at the beginnings or ends of the chapters (especially in volume 1). Volume 2 has a foldout leaf with a schematic sketch of “Chaucers Canterbury Pilgrims” as well as the characters’ heads beneath. At the end are illustrations from Job and Songs. We can be certain that Tennyson read the book—all the pages of the first volume are cut, and so are most of the second volume’s, which means that he at least skipped through William Michael Rossetti’s catalogue. All his life Tennyson felt uneasy about the value attributed to illustrations, and his relationship with his publishers, especially Edward Moxon, was strained in the late 1850s because of disagreements about designs commissioned for his poetry. As Lorraine Janzen Kooistra has argued, by the 1860s Tennyson’s poetry was swept up in “the craze for Christmas gift books” (9). His very successful two-volume Poems (1842) had, by the time he received Blake’s Job, gone through ten editions; Moxon published the first illustrated edition in 1857 on his own initiative. This edition, the Moxon Tennyson, did not meet with Tennyson’s approval. There is no need to expand on why Blake was able to integrate image and text as he wished. Tennyson, however, was expected to accept whatever the illustrator added in terms of style and symbolism. From his point of view, the illustrations were an unnecessary distraction. I think that Anne Gilchrist’s gift showed Tennyson how much the Rossettis had put their stamp on the biography when helping her to complete it, since the extent of their help is credited by Anne in her preface (1: v-vi).

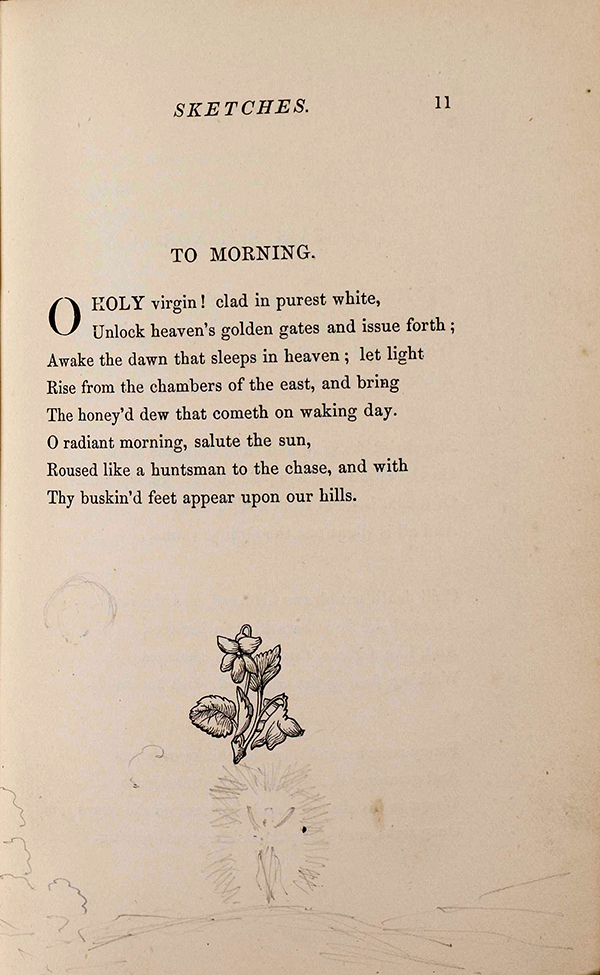

Further evidence for Tennyson’s interest in Blake is his copy of Poetical Sketches (1868), edited by Richard Herne Shepherd and published by Basil Montagu Pickering, the first edition to be published since the original printing of 1783.Poetical Sketches was the companion piece to Pickering’s Songs of Innocence and [of] Experience (1866), also edited by Shepherd; Songs was first published in typescript by Pickering’s father, William Pickering, in 1839 with the Swedenborgian James J. G. Wilkinson as editor. Shepherd’s two small volumes were later combined and published as The Poems of William Blake, Comprising Songs of Innocence and of Experience Together with Poetical Sketches and Some Copyright Poems Not in Any Other Edition (1874). Shepherd compares Blake to Tennyson in footnotes to the poems and concludes the preface: “We need make no elaborate apology for the less happy efforts of a poet who in his best things has hardly fallen short of the large utterance of the Elizabethan dramatists, the pastoral simplicity of Wordsworth, the subtlety and fire of Shelley, and the lyrical tenderness of Tennyson” (xiii-xiv). Tennyson’s copy contains little sketches and doodles on endpapers and one or two pages (see illus. 1). Most importantly, Tennyson added a design to the half-title that echoes Blake’s design for the title page of Job (see illus. 2).

By tradition Job has been listed under Tennyson’s Bibles and is shelved with oversized books. It has been counted toward his interest in commentary on the book of Job, of which there are three works in his library: Le livre de Job traduit de l’Hébreu par Ernest Renan (Paris: Michel Lévy Frères, 1859), A Commentary on the Book of Job with a translation by Samuel Cox (London: Kegan Paul, 1880), and Lectures on the Book of Job delivered in Westminster Abbey by George Granville Bradley (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1887). The copy of Le livre de Job has underlining throughout. Is it by Tennyson? Lectures on the Book of Job has long as well as short vertical lines in the margins, and the half-title is inscribed in Latin “Alfredo Tennyson / Baroni / Poeta Laureato / Viro Nobili Nobili Poeta” (“To Alfred Tennyson / Lord / Poet Laureate / Great Man Great Poet”). The book was presented by the author, Bradley, who was dean of Westminster and chaplain to Queen Victoria. In Cox’s Commentary Tennyson made a small pencil mark beneath the word “Goel” on page 232: “And the great truth he would fain have cut deep on a rock for ever is, that God is his Goel ” (231-32). To better find this page he earmarked it. Tennyson considered projects relating to the Bible and thought about writing his own version of the book of Job, but none of these ideas materialized (Tennyson 2: 52). He, however, thought of Blake’s Job not as an exegesis of an Old Testament book but as an illustrated book. According to one of the notebooks that contain lists and locations of the books at Farringford, he kept it on display with a number of other books.

Around 1855 Tennyson seems to have started cataloguing his library. Most of the lists bear dates, and they are in different hands, suggesting that Tennyson not only returned to this project over a period of years (the last notebook dates from 1887), but also recruited members of his family and friends to help with the task. It appears that he was moving his books around, but the list of illustrated books on the drawing-room table is unique because it is the only example of books’ being displayed on a table. It is also the last list in Tennyson’s hand, covering two pages and amended by Emily Tennyson (see illus. 3).

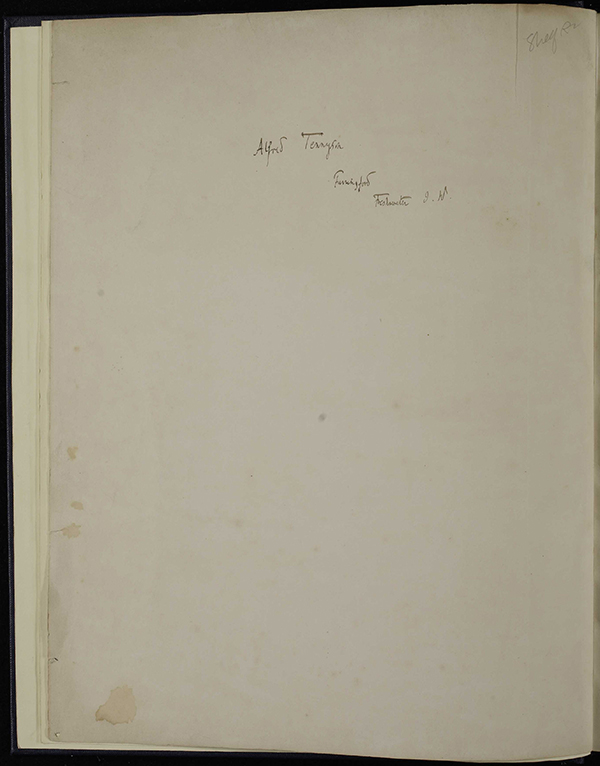

The original binding of Tennyson’s copy of Job is lost; the book is bound like an ordinary library copy in a dark-blue cloth cover. “Illustrations of the Book of Job Blake” is written in gold lettering on the spine. According to the binding repair records, it was rebound in 1979.I am grateful to Grace Timmins for finding this information for me. Job must have been rebound in the nineteenth century, to judge from the different kinds of paper used, but the conservation notes mention nothing of the old binding except “Retain inscription on front end paper.” The first and final leaves—the front and back endpapers—are new paper dating from the 1970s. Then there are two older-looking leaves that date back to the nineteenth century; the first, the flyleaf, is marbled on the recto and has Tennyson’s signature on the verso (see illus. 4).

Most of the leaves have foxing, and there are stains on the leaves with the plates, though they appear a lot weaker on the interleaves. The biggest stain is at its most prominent on the bottom right-hand corner of the title page and the bottom left-hand corner of the facing leaf, becoming fainter as we leaf back to the flyleaf. It is on the recto of the leaf protecting plate 1 but not on the verso. There are also other smaller stains in numerous places, both on the leaves with the plates and the interleaved paper. The foxing does not generally appear in the same places on these two types of paper, suggesting that they aged at different speeds. The leaf with plate 15 has a tear in the lower right-hand corner.

Tennyson’s copy of Job was only rediscovered; during my visit to the Tennyson Research Centre with Diane Piccitto in the spring of 2012, Grace Timmins, the collections access officer, produced it when Diane asked if Tennyson owned any works by Blake.About a year later the Times Literary Supplement printed a short notice about Tennyson’s copy (no. 5753 [5 July 2013]: 3). As mentioned above, it is catalogued with his Bibles but shelved with oversized books.Its reference number is TRC/AT/538. The rediscovery of Job is important insofar as it constitutes further evidence for Tennyson’s interest in Blake and, in particular, Blake’s designs. The real discovery is that Tennyson chose to display it alongside other illustrated books in such a prominent place. This was news to scholars of both Blake and Tennyson, since little work has been done on Tennyson’s use of his books. That he had Job out for his visitors to see and touch suggests that he may have wanted to show it off and also to talk about Blake.

Bibliography

Abbott, Evelyn, and Lewis Campbell. The Life and Letters of Benjamin Jowett. 2 vols. London: John Murray, 1897.

Bentley, G. E., Jr. Blake Books. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977.

---. Blake Records. 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

---. The Stranger from Paradise: A Biography of William Blake. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001.

Bryant, Barbara, comp. “The Job Designs: A Documentary and Bibliographical Record.” William Blake’s Illustrations of the Book of Job. Ed. David Bindman. London: William Blake Trust, 1987. 103-47.

Butlin, Martin. The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake. 2 vols. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981.

Cormack, Malcolm, with an afterword by David Bindman. William Blake: Illustrations of the Book of Job. Richmond: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 1997.

Essick, Robert N. William Blake, Printmaker. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980.

Gilchrist, Alexander. Life of William Blake, “Pictor Ignotus.” 2 vols. London: Macmillan and Co., 1863.

Hoge, James O., ed. Lady Tennyson’s Journal. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1981.

Janzen Kooistra, Lorraine. Poetry, Pictures, and Popular Publishing: The Illustrated Gift Book and Victorian Visual Culture, 1855–1875. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2011.

Jowett, Benjamin. The Epistles of St. Paul to the Thessalonians, Galatians, Romans: with Critical Notes and Dissertations. 2 vols. London: John Murray, 1855.

LaPorte, Charles. Victorian Poets and the Changing Bible. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2011.

Lindberg, Bo. William Blake’s Illustrations to the Book of Job. Åbo: Åbo Akademi, 1973.

Raine, Kathleen. The Human Face of God: William Blake and the Book of Job. London: Thames and Hudson, 1982.

Rowland, Christopher. Blake and the Bible. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

Sung, Mei-Ying. William Blake and the Art of Engraving. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2009.

[Tennyson, Hallam.] Alfred Lord Tennyson: A Memoir. 2 vols. London: Macmillan and Co., 1897.

Wicksteed, Joseph H. Blake’s Vision of the Book of Job, with Reproductions of the Illustrations: A Study. 1910. New York: Haskell House Publishers, 1971.