A Copy of Blake’s Adam and Eve Asleep

Robert N. Essick has been collecting and writing about Blake for fifty years.

Martin Butlin has recently attributed to William Blake a previously unrecorded watercolor drawing of Adam and Eve Asleep based closely on the work of the same title in the series of Blake’s Paradise Lost designs commissioned by Thomas Butts in 1808.Butlin, “Blake’s Unfinished Series of Illustrations to Paradise Lost for John Linnell: An Addition,” Blake 51.1 (summer 2017). For the Butts version, see Butlin, The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake (New Haven: Yale UP, 1981) [hereafter cited as “Butlin” followed by catalogue entry number] 1: 385-86, no. 536.5. Butlin further claims that the newly discovered drawing is a fourth member of the John Linnell series of Paradise Lost designs of 1822 (Butlin no. 537), modeled on the Butts group. I first became aware of this work when a London art dealer kindly sent me a high-resolution JPEG image of it late in August 2016. My first reaction was that the drawing was both beautiful and unfinished, as I told the dealer in an e-mail. As I continued to study the work, I became increasingly disturbed by the weakness (or absence) of pen and ink outlining of forms and the awkward face of the rightmost angel. After e-mail discussions with a few fellow Blake enthusiasts, I concluded that the drawing is a copy of the Butts version by a hand other than Blake’s. This assessment is based on the digital image provided by the dealer; I have not seen the drawing itself.For a rationale for basing attributions on high-resolution digital images, see Essick, “Attribution and Reproduction: Death Pursuing the Soul through the Avenues of Life,” Blake 45.2 (fall 2011): 66-70.

The new version of Adam and Eve Asleep lacks the firm and determinate outlining of motifs in pen and ink typical of Blake’s drawings, including the Linnell group of Paradise Lost watercolors. The pen and ink outlines in Adam and Eve Asleep are rigid and studied, quite unlike Blake’s lively and assured lines. The absence of any outlining on many forms, such as the upper edge of Eve’s left thigh, led to my initial belief that the work was unfinished. Her leg is outlined in Blake’s typical fashion in the Butts design. The faces of the hovering angels are weak and unconvincing in the copy. The work is slavish—yet often inept—in its repetition of the motifs, their shading, and their positions, and lacks the types of variants that usually occur when the original artist is executing a new work based on an earlier model of his own making. For example, in Satan Watching the Endearments of Adam and Eve in the Linnell group (Butlin no. 537.1), the stars in the sky are differently positioned in comparison to its model in the Butts series (Butlin no. 536.4), three stars have been added over Satan’s legs, the sun on the horizon is differently configured, and there are a good many differences in coloring. A much larger halo surrounds Christ’s head in The Creation of Eve in the Linnell series (Butlin no. 537.2) than in its prototype (Butlin no. 536.8), and there are more tree trunks in the background of the Linnell example. Nothing like the great burst of light surrounding Christ in Michael Foretells the Crucifixion in the Linnell group (Butlin no. 537.3) appears in its model (Butlin no. 536.11).

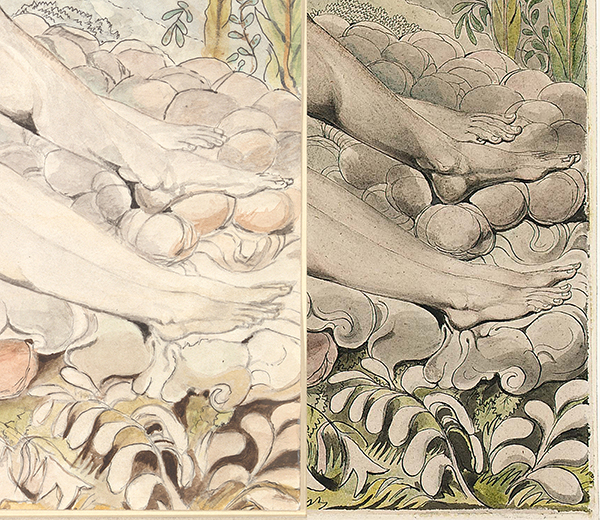

The areas where the newly discovered Adam and Eve Asleep varies from the Butts watercolor look like errors or oversights rather than purposeful revisions. Compared to the crisp outlining and careful shading of Eve’s feet in the Butts version, the rendering of her feet in the copy looks uncertain, haphazard, even amateurish. When a digital image of the Butts version is enlarged, the legs and feet of Adam and Eve retain their integrity; those in the copy become less defined and meaningful (see illus. 1).

Right: Adam and Eve Asleep (Butlin no. 536.5), detail of Adam’s and Eve’s feet. Image courtesy of the William Blake Archive. © 2017 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Accession number 90.102.

See enlargement.

The overall tonality of the Linnell group is consistently richer, deeper, and more vibrant than the source images in the Butts set. Blake’s palette had changed between 1808 and 1822. In contrast, the newly discovered Adam and Eve Asleep imitates the much paler coloring of the Butts version. Even if it is now slightly faded due to overexposure to light, it could never have had the palette of the Linnell drawings. If placed side by side with the Linnell set, Adam and Eve Asleep leaps out as an anomaly in color, outlining, and brushwork. The manner in which shading on figures is rendered is completely different: small strokes with a relatively dry brush in the Linnell watercolors, broader strokes with a wetter brush in Adam and Eve Asleep. The procedure lends volume to rounded forms in the drawings for Linnell; similar motifs in Adam and Eve Asleep remain more two dimensional. All three designs for Linnell are on laid paper, whereas Adam and Eve Asleep is on wove.I am grateful to Joseph Viscomi for this information about the Linnell group. If the work had been executed as the fourth member of the group, one would expect it to be on the same type of paper. Placing the newly discovered drawing in the context of the 1822 Paradise Lost watercolors weakens the case for attributing the former to Blake.

In the absence of provenance information, one must ask how Adam and Eve Asleep became detached from its companions if once part of the Linnell set. His acquisition of the three Paradise Lost watercolors is certain; they remained in the family until their sale in the great Linnell auction at Christie’s in 1918. Only the three drawings are listed in Linnell’s collection in William Michael Rossetti’s 1863 catalogue of Blake’s pictures.In Alexander Gilchrist, Life of William Blake (London: Macmillan, 1863) 2: 212, nos. 91-93. I have not been able to find any record of Linnell or his heirs selling individual Blake watercolors prior to 1918.

I hesitate to propose an attribution for the copy of Adam and Eve Asleep with any assurance. John Linnell might seem an obvious possibility. In 1821 he “traced outlines” of the Butts series of Blake’s Job watercolors, subsequently finished by Blake to create the Linnell set (Butlin no. 551). Linnell may have had access to the Butts series of Paradise Lost illustrations when Blake was copying three of its designs for him in 1822. But why would Linnell copy one of the Paradise Lost watercolors when he had commissioned Blake to prepare at least three? If he had desired a version of Adam and Eve Asleep, he could have added it to Blake’s assignment. We know that Linnell’s children copied some of Blake’s pictures, but they were either too young to produce this watercolor in 1822 (the eldest, Hannah, was born in 1818) or not yet born. A better candidate is Thomas Butts, Jr. (1788–1862). He no doubt had access to the Butts series before his father’s death in 1845, inherited the watercolors at that point, and sold Adam and Eve Asleep in 1853. In 1806 Blake began to give lessons in etching and engraving to the younger Butts, who apparently had some artistic interests and abilities.G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale UP, 2004) 222-23. The most important product of those lessons is an etched and engraved copy of Blake’s wash drawing Christ Trampling Down Satan.Butlin no. 526. For the engraving, see Essick, The Separate Plates of William Blake: A Catalogue (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1983) 214-19. Christ’s profile in the print is poorly executed. The copy of Adam and Eve Asleep shows generally similar, albeit less severe, problems in imitating the angels’ faces in Blake’s original.