A Sketch by Robert Blake Revealed

Robert N. Essick (professor emeritus, University of California, Riverside) and Jenijoy La Belle (professor emerita, California Institute of Technology) have been collecting and writing about Blake for fifty years.

William Blake instructed his beloved youngest brother, Robert (1762–87), in drawing and engraving in the early and mid-1780s. According to Gilchrist, who had “come across” a few of Robert’s “tentative essays” as a draughtsman, “some are in pencil, some in pen and ink …. They unmistakably show the beginner—not to say the child—in art; are naïf and archaic-looking; rude, faltering, often puerile or absurd in drawing; but are characterized by Blake-like feeling and intention, having in short a strong family likeness to his brother’s work” (1: 57). Robert’s extant drawings are listed, and most are reproduced, in Martin Butlin’s catalogue of William Blake’s paintings and drawings. These include Blake’s Notebook, first used by Robert and containing six drawings attributable to him, Robert’s sketchbook of sixty pages, and nine separate leaves of drawings and sketches.Butlin nos. 201.1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 10 (William Blake’s Notebook, British Library), R1 (Robert’s sketchbook, Huntington Library), R2-4, 6-11 (separate leaves, various owners). Butlin no. R5, The Descent of the Holy Spirit (?), has been untraced since 1903 or 1914. Since the publication of Butlin’s catalogue in 1981, one further work has come to light, a pencil sketch of a deathbed scene on the verso of An Invocation (?) (see illus. 2 for the recto).See Essick, “Blake in the Marketplace, 1992” 151 (illus. 9). According to the William Blake Archive, some of the sketches on the last leaf (Butlin no. 149) of Blake’s Island in the Moon manuscript might be attributable to Robert. See <http://www.blakearchive.org/exist/blake/archive/editornotes.xq?objectid=bb74.1.ms.18>. To this modest inventory we can now add one further sketch.

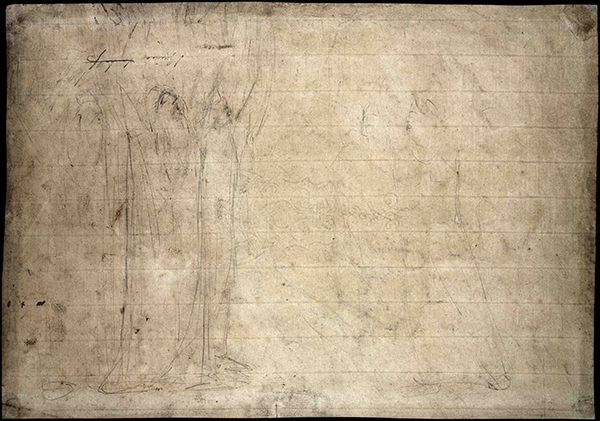

At a 2013 Sotheby’s auction, Robert Essick acquired Joseph Ordering Simeon to Be Bound, a preliminary watercolor by William Blake for the finished work he exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1785.Butlin nos. 156 (finished watercolor, Fitzwilliam Museum), 158 (preliminary watercolor, Essick collection). See Essick, “Blake in the Marketplace, 2013,” illus. 8-9 and their captions. The drawing was firmly affixed along its margins to an acidic mat. Mark Watters, a skilled paper conservator, removed the work from its backing in the summer of 2014 and thereby revealed on its verso a barely visible pencil sketch of figures (illus. 1).

The next figure to the left is represented by the vague outline of a face, apparently turned three-quarters to the left. His body, like his companion’s, may face forward, with a few lines indicating his lowered right arm at his right side, bent slightly at the elbow. This may be an alternative, but quickly abandoned, position for the figure to the right, whose face is at the same level within the composition.

A few lines just left of the right edge of the leaf, particularly in the lower right corner, may be human limbs barely defined. With a little effort, it is possible to see (or imagine) a face in left profile just below and to the left of the top right corner. There may be an eye, a blunt nose, and a downward-curving mouth indicated by a single line. This face, if we are not simply assembling it ourselves from stains and a single pencil line, appears unrelated in size and position to the two heads to the left.

The rightmost standing man in the group left of center faces up and to the right with his right arm slightly bent and extended vertically. A few lines suggest a raised left arm as well. His mouth may be open. A few lines above his head suggest a conical hat of some sort. The face of the next figure to the left is larger and more detailed, including an open mouth, a prominent nose, a right eye, and a full beard. He too faces up in right profile with both arms raised vertically. Clusters of lines just below the top edge of the leaf may include his hands along with some undefined motif to the left. The leftmost figure in this group of three is smaller, possibly because he is standing in the distance. His posture is difficult to determine, but there are slight indications of a face, with eyes, nose, and mouth, facing in three-quarter view to the right. He too has a long beard and either long hair or a hood or helmet over his head. A few sketchy lines above and to the left, close to the left edge of the leaf, may be the bent and raised arm of yet a fourth figure in this group. Between these more or less visible lines is the faint shadow of a head facing left. Far below, just left of the puddled hems of the gowns worn by the first and second figures from the right in this group, a few curving lines indicate something on the ground, perhaps a stone or the lower reaches of the figure (if indeed there is one) furthest left.

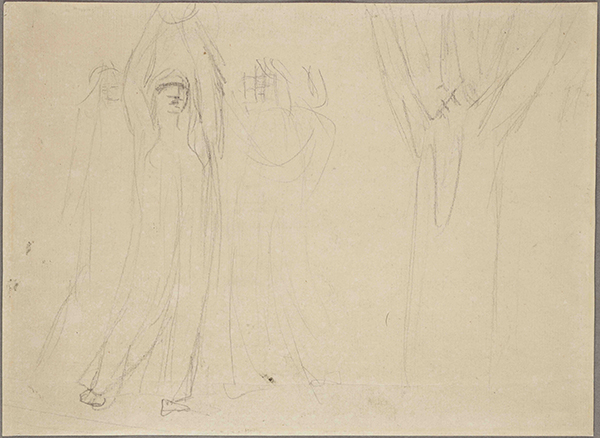

The attribution of the drawing to Robert Blake depends upon stylistic considerations, the expression of the figures’ postures, and the possible subject of the design. Gilchrist’s general comments, quoted above, on Robert’s achievements as an artist are all too readily confirmed by the newly uncovered work. The stiff and awkward strokes of his pencil are easily distinguished from his brother’s flowing, more assured lines, as demonstrated by the watercolor on the recto. A good touchstone for comparison is offered by Robert Blake’s An Invocation (?) (illus. 2).

The verso sketch (illus. 1) includes a pencil inscription upper left, upside down in relation to the sketch but properly oriented in accord with the recto watercolor. This reads “1 guinea for half”, with the last two words lined through.A few pencil lines below and to the left of “for half” might be the word “Lot”, oriented the same way as the sketch, but these lines may be part of the sketch and only look like a word by accident. This is a price, with a fifty percent discount offered but deleted, written by a dealer in the nineteenth century. Other drawings by Blake bear similar verso inscriptions, including a good many acquired by the dealer Joseph Hogarth, probably from Frederick Tatham, no later than the 1850s. Butlin’s provenance record for the preliminary watercolor of Joseph Ordering Simeon to Be Bound begins with “Alexander Macmillan by 1876.” The work may have been in Hogarth’s hands at an earlier date and possibly included among the seventy-eight drawings attributed to “W. Blake” in the 1854 auction of Hogarth’s stock.Southgate and Barrett, London, 7 June and seventeen following days, 1854. Several of the “Blake” lots contained multiple items, most not specified as to title or subject. The thirteen items in lot 1095 are described only as “W. Blake Historical Subjects.” Lot 5082 included “22” works attributed to Blake, of which only ten have been identified by Butlin. Tatham had inherited Blake’s stock of works that remained with his wife, Catherine, until her death in 1831.

We can confidently date the preliminary Joseph watercolor, the recto of illus. 1, to 1784–85 because of the 1785 exhibition of the finished version. We suspect that Robert drew both sketches illustrated here at around the same time: they are on the same laid paper with identical crown and fleur-de-lis watermarks. Which was executed first, the newly discovered drawing or William’s watercolor on the other side of the leaf? We cannot answer that question with any certainty. A light pencil sketch, abandoned by his brother early in its development and with one side untouched, could provide William with a support for a preliminary watercolor. It is equally possible, however, that Blake had no further use for the watercolor once he had produced the finished work for exhibition, and the leaf passed to Robert for his own uses. In either case, this shared piece of paper serves as an apt symbol of the close relationship between the brother artists.

Works Cited

Butlin, Martin. The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake. 2 vols. New Haven: Yale UP, 1981. Cited by catalogue entry number.

Essick, Robert N. “Blake in the Marketplace, 1992.” Blake 26.4 (spring 1993): 140-59.

———. “Blake in the Marketplace, 2013.” Blake 47.4 (spring 2014).

Gilchrist, Alexander. Life of William Blake, “Pictor Ignotus.” 2 vols. London: Macmillan, 1863.