In the long, heat-filled days that compose a typical Spanish summer, an exhibition of William Blake’s work appeared in Madrid, the first in Spain since 1996. A collaboration between Spain’s La Caixa Foundation—also the organizers of the nation’s first showing of Blake in 1996—and Tate Britain, the exhibition presented Blake as a leading icon of British art, a rebel artist who inspired subsequent generations of artists.

The venue is an interesting starting point. La Caixa is essentially a savings bank, its logo designed by Joan Miró, which operates as a nonprofit bank among dozens of such banks in Spain, whose collective mission is to give back to communities by investing in public welfare projects including scientific, cultural, social, and research programs. The CaixaForum, a four-story converted electrical building with a mass of reddish-orange oxidized iron as its crown, is juxtaposed nicely with the greenery of Spain’s largest vertical garden, designed by French botanist Patrick Blanc, and is located in the center of Madrid, steps away from the Prado.

The exhibition displayed works by Blake ranging from engravings to watercolors to prints and temperas, covering the breadth of his artistic career. Over eighty works, mostly from the Tate’s collection, demonstrated his range in terms of size, method, and theme. According to the exhibition materials, the intent was to highlight Blake as “one of the most influential figures” in British cultural history, a visionary who anticipated the artistic movements that followed, namely the Pre-Raphaelite, neoromantic, and postmodern movements. The annotated journey through the artist’s creative vision ended with a review of his artistic legacy.

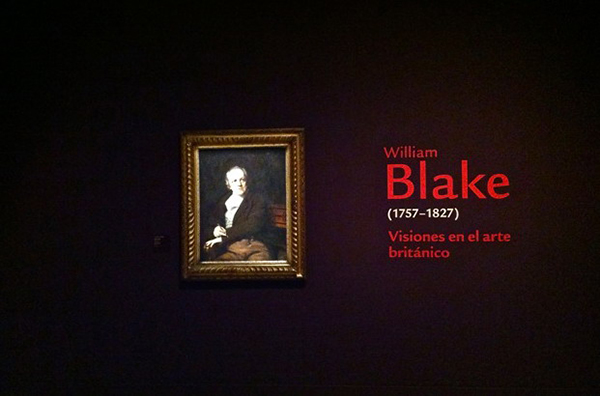

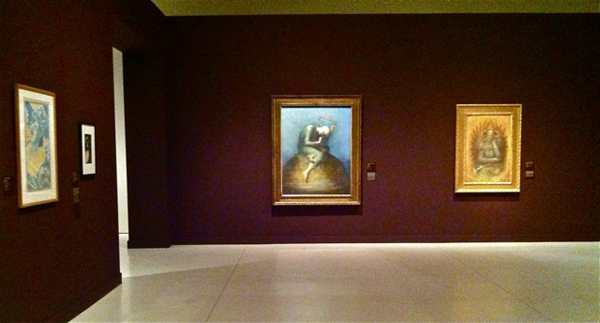

For me, the journey began with a primarily visual sensation: the color of the walls, a striking aubergine emblazoned with red-toned text for headlines, seemed to have been chosen to set off the textured whites and yellows in nearly all of Blake’s work exhibited. Visitors were greeted at the entrance by Thomas Phillips’s 1807 portrait of Blake hanging on the dark purple wall of the anteroom, and then moved through the exhibition’s twelve sections and subsections, labeled in both Spanish and English, all of which served to impress upon the viewer that Blake was a versatile artist who experimented widely with technique, medium, and theme. The exhibit was organized thematically rather than chronologically in order to articulate its premise that Blake stood apart from other artists of his time.

Sections highlighted his various methods and thematic concentrations. The first, emphasizing his early artistic life as an apprentice, was disappointing in that it featured only two pieces that were not engravings. However, these pieces served as a starting point for the assertion that Blake was, even in his early career after his time at the Royal Academy, unconventional in the production of ideas through his art. His Age Teaching Youth (c. 1785-90), a small meditative work where the humanized figures of experience and innocence sit side by side, was juxtaposed with the more conventional Oberon, Titania, and Puck with Fairies Dancing (c. 1786).

To illustrate further his imaginative and metaphorical approach, there was a focus on his self-created mythologies, which the exhibit declared his “most complex and original works,” in an area dedicated to Blake’s prophetic books. The human body, especially the body of Urizen, was the centerpiece of these works, in which soft, contoured lines delineated tormented poses and expressed radical representations of terror. The viewer was prompted to glean Blake’s political tendencies in this section. His Visions of the Daughters of Albion (1793), where we see both men and women enslaved, chained to immovable rock, was presented as a commentary on sexual freedom, gender roles, and equality.

In addition to introducing Blakean themes, there was also an emphasis on technique. An area featured his innovative use of tempera by employing the technique of defining lines and contours in black ink after applying layers of gum-based color, highlighting Blake’s belief that a work of art was all the more perfect “the more distinct, sharp, and wirey the bounding line.” Works exemplifying the variety of materials used by Blake, such as canvas atop cardboard, iron, or pine—the latter used for Winter (c. 1820-25), which is nearly completely white—were displayed alongside the spiritual portraits of contemporaries William Pitt and Lord Nelson. One of Blake’s more delightful, imaginative works, The Ghost of a Flea (c. 1819-20), was featured prominently. Crowds gathered around it, perhaps to read the lengthy label describing its origin as one of Blake’s magical visions, or perhaps to glimpse its fine detail despite its diminutive size.

In a slightly out-of-the-way area, next to a room of Blake’s unfinished series for the Divine Comedy (from the 1820s), images of pages from a copy of Songs of Innocence and of Experience were projected along with a digital “page turner” of his Notebook, so one could turn its many pages by swiping a screen. Each page included very detailed descriptions in both English and Spanish. The space underscored the interrelationship between writing and image, the realm in which Blake really shone, which was clear even in translation.

To prompt the link between Blake and artistic movements that followed, his tiny wood-block engravings for The Pastorals of Virgil (1821), featuring mainly pastoral scenes, were presented as antecedents to works of the group of acolytes who called themselves the Ancients, displayed in the same room. It was difficult to miss the nearly identical shepherd figures of Blake’s Thenot in the frontispiece for The Pastorals of Virgil and George Richmond’s “The Shepherd” (1827). The Ancients admired Blake’s visionary genius; however, theirs was a more nostalgic worldview akin to late romanticism and lacking the social-critical inference of Blake’s oeuvre.

In contrast, Blake and the Pre-Raphaelites shared similar visual and ideological interests. Visualizing mythology was one such parallel. For the Pre-Raphaelites, of course, this often meant the depiction of Arthurian myth. The more radical Pre-Raphaelites appreciated Blake’s visionary approach and his belief in the role of the artist as prophet-philosopher. Here, work by the movement’s great artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti—a “complete” artist like Blake—offered direct thematic ties to Blake with a Dante-inspired wood engraving, and also technical similarities of medium, the human form, and spatialization (How Sir Galahad, Sir Bors, and Sir Percival Were Fed with the Sanc Grael [1864]). Also mentioned was Rossetti’s involvement, along with Alexander Gilchrist, in Blake’s biography, which helped to establish Blake’s eminence in British art.

Radicalism being the link, pieces from the symbolists were shown to delineate again a more ideological connection with Blake. They were advocates of the prophetic role of the artist and viewed Blake as their ancestor. In the soft-colored, spiritually themed works of George Frederic Watts, the ink of Aubrey Beardsley, and a stark lithograph of Charles Shannon, among others, recurrent mythological themes and the prominence of lines were unmistakable.

Lastly, the exhibition pointed toward Blake’s legacy with examples from the twentieth-century neoromantic movement. Due to a lack of explanation, the connection to these artists was more tenuous, despite the display of a small-scale version of Eduardo Paolozzi’s sculpture Newton (1988) and the thematic parallels and dramatic reds of Cecil Collins’s The Fall of Lucifer (1933), which appeared to be a direct reworking of Blake’s work of the same name for the book of Job. Some of the works supplied here had closer connections to surrealism or expressionism than they did to Blake; take, for example, Collins’s The Poet (1941), with its triangular figures set in a Daliesque landscape. This was one of the weaknesses of the exhibit. The areas that stressed Blake’s influence on these movements could have been more extensive, if not more fully explained through direct comparisons or commentary. I found the connections to be vague, especially in the case of the neoromantics, whereas there were such rich descriptions in other areas of the exhibition. In addition, the digitalized image area, including Blake’s chronology, should have been located more prominently.

Late in the summer I corresponded with the exhibit’s coordinator, Eduardo Rostan Robledo, who works at the CaixaForum Barcelona; he reported that interest had been very high. When I visited the exhibit in its first week (the first of many visits) it was full of people and the din of whispers and admiration. In Spain, Blake has often been referred to as “el Goya inglés,” the English Goya, comparing him to the nation’s most revered painter of the romantic era. The comparison, of course, refers to the artists’ singular styles and sometimes subversive approach to their subjects. Spain already loves him. It verifies that, as the exhibition materials suggest, Blake’s prestige and legacy only increase with time. Blake, like Goya, whose paintings hang across the street at the Prado, deserves a prominent place in the realm of art. He endures, marking the canvases of later generations, much like the vermilion still glowing bright in his own work.