Christopher Rowland’s deeply scholarly account of William Blake’s relationship with the Bible marks Blake out as a theologian as well as a poet and artist. At the heart of the book is a fascination with biblical exegesis as an imaginative activity, and it is this that makes Rowland’s work a truly valuable contribution to Blake studies and to the growing body of critical literature that takes the relationship between literature and theology as its subject. Notwithstanding a strong literary interest, Rowland’s objectives are clearly theological. He writes, “Engagement with [Blake’s] work reshapes the way in which one reads the Bible, views and experiences the world, and for that matter, God” (1). By developing and nuancing our understanding of Blake’s sense of the way text participates in affective religion, he shows how reading Blake might perform such immense tasks. Rather than encouraging us to see text as simply the dead letter of Urizenic law, Rowland takes on one of the fundamental contraries in Blake’s art and tackles the idea of text as a living body, born again in each imaginative interpretation, and effective insofar as it is affective for the individual reader.

One of the most striking implications of Rowland’s approach is that Blake’s prowess as imaginative exegete provides a way into negotiating his own illustrated texts. In the final event, Rowland acknowledges that Blake makes little distinction between the Bible and other great works of literature, claiming,

For Blake, the words of the Bible were not those which somehow contained something peculiarly holy or special. Blake’s focus on the effect of text, whether the Bible, or his own allusive illuminated texts, suggests that texts are less an object to be explained than a stimulus to the exploration of the imaginative space that biblical texts may offer. … If [the Bible] worked as a text, to enable humans to change, then its role spoke for itself. (242)Rowland’s final leveling of the Bible with other great texts seems a remarkably brave theological position. If the Bible only “works” with an imaginative exegete such as Blake (who makes the text as much as he is made by it), then it is fairly redundant in the hands of a less privileged reader. God is made by man, and not the other way round. In one sense, this is another way of affirming Blake’s belief that imagination is the quintessential religious faculty. Without imagination, no text can live, and the Bible is a dead book. But it also means that Rowland breaks new ground in considering what this religious faculty of “imagination” might mean in exegetical terms.

It is not surprising that Rowland places considerable emphasis on exegetical disposition. An inner openness and resistance to Enlightenment thinking have long been recognized as definitive in Blake’s exaltation of the imagination. Rowland is broadly supportive of existing work on Blake and religion and is extremely generous in his allusions to other Blake scholars. Like Jon Mee in Dangerous Enthusiasm (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992), he emphasizes that Blake’s religious radicalism should be seen as part of a radical eighteenth-century millenarianism that bears comparison with that of Richard Brothers and has antecedents in the work of Jacob Boehme. Yet implicit in the detailed scholarly analysis that Rowland undertakes is the idea that disposition without education and understanding will not make for imaginative exegesis. The real strength of Rowland’s contribution lies in his profound knowledge of the biblical text and the years of theological study informing and directing his interpretations. In other words, it is evident on every page of this book that education forms part of imaginative exegesis. Rowland’s exegesis, like Blake’s, rests on close reading and the ability to unpack densely allusive verbal and visual textures. In this way Rowland makes a place for thought in the religion of the heart and in its enabling faculty of imagination.

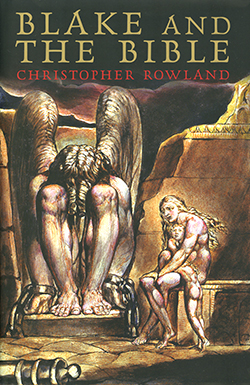

Rowland takes Blake’s set of engravings to the Book of Job as his only full commentary on a biblical text, and as the basis from which to draw out distinctive features of Blake’s exegesis. This works well, as it gives the reader a way into the enormous body of Blake’s work and allows Rowland a focus for his analysis, which naturally spreads to Blake’s other writings and illustrations. Chapters explore the biblical hermeneutics of Blake’s Job engravings, divine contraries, the meaning and importance of prophecy, Blake’s place in the history of radical biblical interpretation, Blake’s relationship with Jesus and Paul, and his interpretation of the Bible through images. The book is beautifully illustrated, and Rowland takes a holistic approach, bringing words, images, and historical context to bear on our understanding of Blake’s stature as biblical exegete. In the chapter on prophecy, for instance, he contextualizes Blake with examples of the prophetic enthusiasm of late eighteenth-century and early nineteenth-century Britain, as well as with examples of biblical prophets such as Ezekiel. He argues that Blake’s “distinctive contribution was brilliantly to encapsulate an aspect of biblical prophecy in his focus on the ‘minute particulars’ of contemporary life” (122). Rowland emphasizes the creative impetus of Blake’s obscure style, claiming that the problematic and often tenuous links between text and image mean that the pursuit of understanding needs to be creative (129). In other words, Blake’s prophetic style requires participatory involvement from the reader, making interpretation an imaginative act as opposed to passive reception of meaning. Style is therefore intrinsically connected to value, as the function of a prophetic text is to “rouze the faculties to act” (E 702, quoted on 130).

There can be no doubt that Rowland’s case for Blake as a brilliant biblical exegete is persuasive and timely. The complexity of Blake’s thought, the quality of his composite art, and the context in which he needs to be understood are all hugely enhanced by the wealth of theological learning and biblical knowledge that Rowland brings to this book. Yet one cannot help but feel that the theological and artistic conviction that motors the argument, and that finds itself reflected and shaped in numerous ways by Blake’s own poetic magnitude, does not allow for any consideration of the limits that, Blake felt, constrained his own craft.

Rowland identifies Los as the spirit of the prophetic imagination in Blake’s mythology. Los is where we must put our faith. But Blake revealed his dissatisfaction with the role of the prophet-artist as early as 1793. An early version of the Preludium to America a Prophecy ends:

The stern Bard ceas’d, asham’d of his own song; enrag’d he swungIn Night 5 of Vala, the prophetic Los binds the revolutionary Orc in the chains of Urizenic repression, and by the end of Vala the prophetic function is recognized as a distraction, a “delusive Phantom” (E 407). Blake was troublingly aware of the possibility that the sacred quality of imagination may not always be effective. The only lacuna in Rowland’s book is the fact that, in celebrating Blake’s triumph, it misses his sense of frustration.

His harp aloft sounding, then dash’d its shining frame against

A ruin’d pillar in glittring fragments; silent he turn’d away,

And wander’d down the vales of Kent in sick & drear lamentings. (E 52)