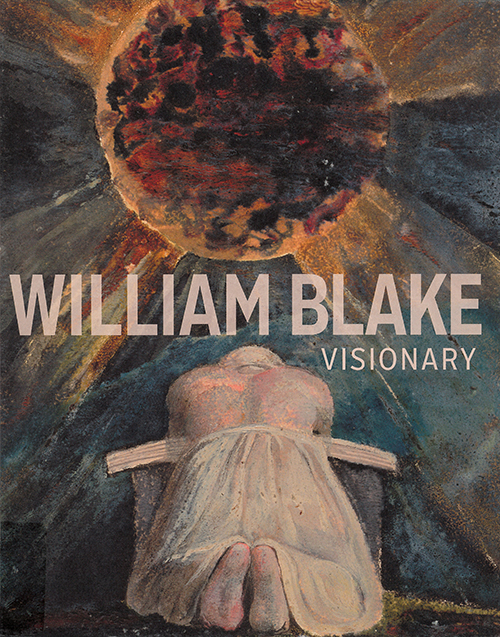

A figure seen from the back kneels at an altar before the glaring, darkened form of a numinous planet. As a frontispiece this image marks the entrance to The Song of Los, and now it also leads us into William Blake: Visionary, the stunning catalogue of the Getty exhibition that was due to open from 21 July to 11 October 2020, but has been postponed to fall 2023 because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The back cover fulfills the allusion to the book as a prophetic space with another Rückenfigur: the heroic naked form of Milton, hand upraised, whether to close the catalogue or carve its way through the binding, tracing a reverse infernal route through the back. The preliminary pages guiding our first steps into the Getty Blake start with the Three Maries—a detail from The Entombment, a watercolor from the Tate’s Robertson bequest—followed by the title page, superimposed on the mysterious chicken-headed figure brooding over the setting sun in Jerusalem plate 78. This interleaving of pagan and Christian images shapes the syncretic imaginary of Blake’s visionary worlds. Splendid full-page illustrations mark the partitions of this handsome book: a detail from Laocoön faces the foreword, The Night of Enitharmon’s Joy, or Hecate, the acknowledgments, the star hitting William’s left foot the introduction, and plate 25 of Jerusalem Edina Adam’s essay on “William Blake’s ‘Bounding Outline’: On the Sources of Artistic Originality,” while the frontispiece to Jerusalem opens the door to Matthew Hargraves’s essay, “America’s Blake.” Hargraves’s argument is illustrated with some of the arresting acquisitions by American collectors, beginning with an impression of Nebuchadnezzar, bought by Henry Adams from Francis Turner Palgrave and now in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and The Virgin Hushing the Young John the Baptist, acquired by Edward William Hooper.

The Getty exhibition results from a collaboration with Tate Britain, which suggests a traveling exhibition adapting the 2019–20 Blake retrospective for an American public. Yet a comparison between their respective Blakes reveals different local dynamics. While the Tate’s Blake roots the poet’s work within its London neighborhoods and communities, the Getty exhibition aims to bring “the artist and his works to a wider US audience” (11). Timothy Potts, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum, indicates that apart from displays at the Huntington supplemented by the collection of Robert N. Essick, this is the first loan exhibition of Blake’s works on the West Coast since 1936, when a selection from Lessing J. Rosenwald’s collection was exhibited by Alice Millard at the Little Museum of La Miniatura, her Pasadena home designed by Frank Lloyd Wright (7). The Getty catalogue is dedicated to Essick, the team’s “Blake helpline” through “deep, dark, and often mysterious waters” (9).

Hargraves’s essay reconstructs “America’s Blake” with a fascinating account of Bostonian acquisitions, from Adams in contact with Richard Monckton Milnes and Palgrave in London in the 1860s to an alternative, transcendentalist route of appreciation that dates back to the correspondence of Anne Gilchrist, who brought Blakes on her move to Concord and Boston in 1878. The mediation of book dealer Bernard Quaritch enabled Hooper, the treasurer of Harvard, to acquire Jerusalem copy D. In 1880 the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston exhibited Blakes loaned from Gilchrist, together with recent American purchases: Horace Scudder’s Job, Hooper’s The Virgin Hushing the Young John the Baptist, and Adams’s Nebuchadnezzar. In 1891 the museum held a second exhibition, showcasing its own recently acquired watercolors—the first institutional Blake acquisitions by an American collection—alongside loans from some of the contributors in 1880 and other private collectors.Museum of Fine Arts, Print Department, “Introductory Note,” Exhibition of Books, Water Colors, Engravings, Etc. by William Blake, 7 February–15 March 1891 (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1891) iii. This Bostonian context is also relevant to the trajectory of the greatest Blake collector, the Harvard graduate and Unitarian banker William Augustus White, who started collecting rare books in the 1880s, first focusing on Renaissance emblem books. Between 1890 and 1908 he acquired nineteen copies of Blake’s illuminated books, as well as the series illustrating Milton’s L’Allegro and Il Penseroso and the 537 watercolors drawn around the pages of first and second editions of Edward Young’s Night Thoughts.Robert N. Essick, “Collecting Blake,” Blake in Our Time: Essays in Honour of G. E. Bentley Jr, ed. Karen Mulhallen (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010) 19-34, on 23. At this point, Hargraves’s account enters territory carefully charted by Essick on the collecting of White and Pierpont Morgan in New York, Henry Huntington in California, Chicago-born Rosenwald in Philadelphia, and Yale graduate Paul Mellon.

The tension between Blake’s transnational appeal and impulses to preserve British masterpieces for the nation is captured through an evocative quotation from an article by Robert Ross in the Burlington Magazine in 1909. Ross elegantly undermines impulses to preserve Blake for the nation through a counterfactual comparison of his widow, Catherine Blake, to the goddess Isis trying to recover and piece together the fragments of Osiris, thereby underlining the absurdity of an impossible task that goes against the spirit of Blake’s “scattered identity”: “No one would have resented more than he the attempts of any national Art-Collections Fund to stay the tide of his Prophetic Books ebbing to America.”Robert Ross, “A Recent Criticism of Blake,” Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 16.80 (November 1909): 84-87, on 84. In other words, Ross’s intervention harnesses Blake to the transnational position of the art dealer in a discussion about national art policies among dealers, private collectors, and those who advocated a concerted national effort in the pages of the journal, whose editorial board included founders of the National Art Collections Fund, established six months after the journal itself in 1903.On the National Art Collections Fund, see Helen Rees Leahy, “‘For Connoisseurs’: The Burlington Magazine 1903–11,” Art History and Its Institutions: Foundations of a Discipline, ed. Elizabeth Mansfield (London: Routledge, 2002) 231-45, on 240-45; and Barbara Pezzini, “The Burlington Magazine, The Burlington Gazette, and The Connoisseur: The Art Periodical and the Market for Old Master Paintings in Edwardian London,” Visual Resources 29.3 (2013): 154-83, on 164-66. Contrast Ross’s argument to the proposal to levy a sales tax on art purchases “with the view of placing our national purchasing powers on an equality with our national prestige” in order to curb the power of American and German buyers (“The National Art-Collections Fund,” Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 10.45 [December 1906]: 141). An editorial published four months before Ross’s intervention supported the king’s suggestion “of a reserve fund, for the immediate purchase of indispensable works of art if they should ever come into the market,” and dismissed “any scheme of registration and restriction after the Italian fashion” (“A Purchase Fund for Works of Art,” Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 15.76 [July 1909]: 201-02, on 201). In 1917 Ross was appointed London adviser to the Felton Bequest at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne. When the Linnell collection came up for sale at Christie’s in 1918, he partnered with the National Art Collections Fund in the purchase of Blake’s Dante watercolors. Arguably, this partnership prevented an American bid to buy the entire set.Hargraves 32; on Ross’s appointment and dealings with the National Art Collections Fund, see Irena Zdanowicz, “Introduction: The Melbourne Blakes—Their Acquisition and Critical Fortunes in Australia,” Martin Butlin and Ted Gott, William Blake in the Collection of the National Gallery of Victoria (Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 1989) 10-19, including Ross’s letter to the National Gallery of Victoria, 30 June 1918, on 11-12. Hargraves also details the nationalist impulse animating American collecting, evident in the 1939 exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which was curated by Elizabeth Mongan, the keeper of the Rosenwald Collection: “No loans were invited from Europe, one object of the exhibition being to show what a great wealth of Blake material is now in America.”Henry P. McIlhenny, “Note of Acknowledgment,” William Blake, 1757–1827: A Descriptive Catalogue of an Exhibition of the Works of William Blake Selected from Collections in the United States (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1939) xix, quoted in Hargraves 33. This ambition was crystallized in Rosenwald’s bequest to the nation, distributed between the Library of Congress and the National Gallery of Art between 1941 and 1943.The collection was housed at Alverthorpe, Rosenwald’s estate in Jenkintown, Pennsylvania, until his death in 1979.

Hargraves’s account also pays attention to the women who shaped ways of reading and collecting Blake in America, from the transcendentalist route associated with Anne Gilchrist and Hooper’s mother, the poet Ellen Sturgis, to Julia Atterbury Thorne, whose collection was gifted to the Morgan Library in 1973, and the psychoanalytical interests of Mary Conover Mellon, who introduced Paul Mellon to the work of Carl Jung. He traces the Mellons’ turn to collecting to their acquaintance with Jung through repeated visits to Switzerland between 1938 and 1940, and shared interests with Jung in Blake, alchemical books, and collective archetypes, before they bought their first Blake in 1941.Hargraves 33; for a more extensive discussion of this point, see Hargraves, “William Blake and Paul Mellon: The Life of the Mind,” Public Domain Review (7 October 2014), <https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/william-blake-and-paul-mellon-the-life-of-the-mind>, accessed 3 May 2021.

Edina Adam’s “William Blake’s ‘Bounding Outline’: On the Sources of Artistic Originality” expertly guides the reader through a formalist introduction to Blake’s corpus from the standpoint of artistic traditions, techniques, and materials. The curatorial imprint shapes the partitions of the book, with three of the six sections roughly divided according to different types of production, as printmaker, painter-illustrator, and the painter-poet of the illuminated books. Each is introduced with a splendid full-page illustration, captioned with a topical quotation. “The Professional Printmaker” is captured by the emblematic choice of a tearful, kneeling Job from “The Just Upright Man is laughed to scorn,” the plate numbered 10 of Illustrations of the Book of Job: “Engraving is the profession I was apprenticed to, & should never have attempted to live by any thing else If orders had not come in for my Designs & Paintings ….”Letter to the Reverend Trusler, 23 August 1799 (E 703). This section tracks the phases of Blake’s printmaking: his apprenticeship to James Basire, exemplified by a plate from Richard Gough’s Sepulchral Monuments in Great Britain (1796); his engraving after Hogarth’s The Beggar’s Opera for John Boydell; a series of etchings and engravings from the Essick collection—Blake’s engraving of Michelangelo after Henry Fuseli for Fuseli’s Lectures on Painting, his white-line etching of Deaths Door, compared to Schiavonetti’s version published in 1808, the Narcissa title page from Young’s Night Thoughts, and relief-etched and wood-engraved illustrations to Thornton’s The Pastorals of Virgil; and the Huntington’s Illustrations of the Book of Job. So far the section has traced different phases and printing techniques; the watercolor Dante illustrations at the end seem out of place. It might have made more sense to have arranged the watercolor and the engraving of The Pit of Disease: The Falsifiers on a page spread for ease of comparison, and to have placed the others in a section specifically devoted to watercolor, documenting illuminating remarks on the medium in Adam’s essay.

A reproduction of the Tate’s impression of the color print Nebuchadnezzar, above a quotation from another letter to Trusler, earlier in August 1799—“I find more & more that my Style of Designing is a Species by Itself”—marks the beginning of the section on “The Painter-Illustrator.” Julian Brooks rightly comments that “sometimes his [Blake’s] illustrations seem akin to adaptive theatrical performances of texts, or personal commentaries; often they are deeply spiritual meditations, intrigued explorations, or free associations” (67). At the Tate retrospective, this point was beautifully borne out by the wall dedicated to the biblical watercolors that Blake painted for Thomas Butts. This section of the book encompasses a broad range of biblical, Shakespearean, and Miltonic subjects in different media: watercolor, tempera, and the large color prints, but also Blake’s watercolor illustrations to his late illuminated manuscript of Genesis and a partly hand-colored impression of the etching/engraving of “Chaucers Canterbury Pilgrims.” The selection gives much to think through, though the logic of the sequence is hard to discern, since the plates are not arranged in chronological sequence, nor thematically.

A magnified detail of “The Tyger,” including the last two stanzas and the tail vignette, sets the terms of “The Painter-Poet,” along with words from Blake’s address To the Public: “If a method of Printing which combines the Painter and the Poet is a phenomenon worthy of public attention, provided that it exceeds in elegance all former methods, the Author is sure of his reward” (E 692). After a helpful and clear account of the relief-etching method, this section is divided between Songs—title page, “Laughing Song,” “The Sick Rose,” “The Fly” (Huntington), “The Tyger” (Yale Center for British Art), and “The Shepherd” (Essick collection)—and impressions from the Tate of the so-called Small Book of Designs copy B, a selection of plates reprinted from the illuminated books without the accompanying text. While Blake repurposed these plates with emblematic lines penned in as captions, the catalogue entries follow the Tate’s practice of referencing the illuminated books the designs were first composed for, obliterating their new identities as separate works in their own right.

The section devoted to “Blake’s Contemporaries” is introduced by a detail from John Flaxman’s ink, watercolor, and graphite drawing Alcestis and Admetus, captioned with words that Blake directed to Flaxman: “It is to you I owe All my present Happiness It is to you I owe perhaps the Principal Happiness of my life” (E 707). This arresting emblem invites the reader to make myriad connections. The “Friend & Companion from Eternity” (E 710) certainly was a key figure for Blake from the time of his first steps out of his apprenticeship with Basire, providing friends, patrons, and commissions. The introductory text could have fleshed out how important Flaxman and his network were for Blake, from the Mathews, who helped publish Poetical Sketches, to George Romney and William Hayley, who was the prompt for Blake’s only experience outside London. Identifying specific connections between Blake and Fuseli would also have been helpful in situating Blake’s work in relation to other artists. Granted, this is hard to accomplish in the one-page format of the introductions to the sections, with so much to cover here, from the classicizing idiom of late eighteenth-century cosmopolitan art (represented in the plates by Benjamin West, James Barry, Fuseli, and Flaxman), to the Royal Academy, Romney (whose context is unexplained), and James Gillray, who exemplifies satirical ways of seeing “outside the art establishment,” which again raises more questions than it can answer.

“See Visions, Dream Dreams, & prophecy & speak Parables unobserv’d & at liberty from the Doubts of other Mortals” (E 728): Blake’s words to his patron Butts, inscribed below an enlarged detail showing Orc emerging from the flames, his arms thrust outwards, measuring the space of the page, prepare the reader for “The Visionary.” This section reproduces Yale’s copy of America in its entirety, as well as the frontispieces of Europe a Prophecy, Visions of the Daughters of Albion, and The Song of Los, followed by a portrait by John Linnell of John Varley as a way into the Visionary Heads series—Merlin and Queen Eleanor from the collections of Essick and the Huntington, joined by the Tate’s The Head of the Ghost of a Flea and the famous tempera.

Heroic forms wielding hammer and compasses from the last plate of Jerusalem inaugurate the final section, “The Mythmaker,” captioned with Los’s words “I must Create a System, or be enslav’d by another Mans / I will not Reason & Compare: my business is to Create” (Jerusalem 10.20-21, E 153). Blake’s watercolor Landscape near Felpham (c. 1800), loaned from the Tate, signals his Sussex period, though instead of introducing his relationship with Hayley and the role of Hayley’s Milton scholarship in Blake’s prophetic poetry, it is oddly placed between plates from the Huntington’s Milton and Yale’s Jerusalem. “Joseph of Arimathea among the Rocks of Albion” (c. 1820) and Laocoön (1826–27) conclude the volume. There is no discussion of “Joseph of Arimathea” and its reworking. Both the Tate and the Getty chose to exhibit the second state, from impressions from the Fitzwilliam and Essick respectively. This seminal work might have been discussed in “The Professional Printmaker”; alternatively, it might have been explored in the introduction here, either as part of Blake’s Christian myth of Britain in relation to “Jerusalem” from the preface to Milton or in connection with Blake’s mythical genealogy of gothic art, given that his inscription presents Joseph as “One of the Gothic Artists who Built the Cathedrals.” Laocoön is also rearticulated through time: the graphite copy of the sculpture that Blake produced for the engraving illustrating Flaxman’s entry on sculpture in Rees’s Cyclopædia is in the exhibition checklist, but neither reproduced nor discussed in the catalogue, a missed opportunity to think of reproductive engraving as a mythmaking process of invention. Articulating these connections in the introductory text would have clarified why these two works are such an effective ending to the volume. The choice of two works from the Essick collection is another means by which the visual apparatus honors the volume’s dedicatee. The book comes full circle, then, celebrating the Blake collections in California through visionary specimens from the Huntington on the book covers, replicated by the disposition of plates inside, where Laocoön marks the end by going back to the beginning, since a detail from it acts as a full-page illustration facing the foreword. This is bibliographic design at its best.

In view of the exhibition, Getty Publications accompanied the catalogue with a small volume, Lives of William Blake, which “offers an intimate portrait of the passions, pursuits, and mind of the enigmatic artist William Blake.”Back cover blurb. This handsome book, originally published by Pallas Athene in London in 2019, is introduced by Martin Myrone, who curated the 2019–20 Tate exhibition with Amy Concannon. In his introduction he points out that the image of “the Cockney visionary, wild-eyed Soho eccentric” is “a modern fabrication, crafted to match our complacent myths of creative self-fulfillment and social mobility” (24). The “anachronistic possibility” of artists looking back to “the old world of the medieval workshop and early renaissance print studio” (16) is set against the contemporary field of art defined by academies, galleries, and dealers. Building on the scholarship of G. E. Bentley, Jr., about Blake in the marketplace, Myrone’s historicizing approach to Blake’s life as an artist draws on Benjamin Malkin’s account of his apprenticeship and Royal Academy training.

The selection reprinted in the volume documents the image of the artist emerging from early accounts. Henry Crabb Robinson’s “William Blake, Künstler, Dichter und religiöser Schwärmer” (“Artist, Poet, and Religious Mystic”), published in German in the second volume of Vaterländisches Museum in 1811 and here reproduced from a revised translation originally published in 1914, demonstrates how Blake was introduced to German readers. Crabb Robinson’s “Reminiscences” supplement that account with personal recollections of “the wild and strange rhapsodies uttered by this insane man of genius,” afflicted by “monomania,” fueled by the “theosophic dreams” (29) of the religious mystic. J. T. Smith’s “Biographical Sketch of Blake,” first published in Nollekens and His Times (1828), shows Blake laboring against the “stigma of eccentricity” (121) and follows him through his professional development, “manly firmness of opinion” (124), and “frugal” attitude to money (132). Blake’s artistic networks are detailed through specimens of letters that Smith obtained as a collector of autographs, including Blake’s address to Flaxman as “Dear Sculptor of Eternity” (137). Smith’s sketch shows a fellow engraver’s sense of the difficult juggling of commissions and the need for patronage, detailing Blake’s falling out with Thomas Stothard over the Canterbury pilgrims and suggesting how hard it was for someone whose “effusions were not generally felt” by the “uninitiated eye” to find work (141-46, 149). Smith adds descriptions by the antiquarian Richard Thomson of Blake’s works in the collection of Ozias Humphry’s son, William Upcott. Their coming together documents the circulation of Blake’s works in the 1820s among engravers, antiquarians, and autograph collectors, who straddled private networks and emerging cultural institutions: Smith was keeper of prints and drawings at the British Museum, Upcott sub-librarian of the London Institution, and Thomson a longtime user of the London Institution before he became one of its joint librarians in 1834. Going against the early biographic evidence of Blake’s networks, Alexander Gilchrist’s “Preliminary” to Life of William Blake, “Pictor Ignotus” (1863) crystallizes the Victorian view of the unpublished, unknown, “solitary, self-taught, and as an artist, semi-taught Dreamer, ‘delivering the burning messages of prophecy by the stammering lips of infancy,’ as Mr. Ruskin has said of Cimabue and Giotto” (181). Such is the poet’s “semi-utterance snatched from the depths of the vague and unspeakable” (187). Blake’s lives are complemented by a stunning selection of color reproductions detailing his work—at the start his prophetic portrait, Urizen holding the open book of prophecy, and the entrance to Dante’s hell; at the end the bearded figure leaning on his staff and leaving the picture through a door in the bark of a tree, from America.

The postponement of the exhibition separates the books from the displays, but in the absence of the accompanying experience of the originals, both catalogue and lives eloquently activate the reader’s imagination, raising the hope that this splendid selection of works will be offered at a safer time in the future.