Network Theory and Ecology in Blake’s Jerusalem

Jade Hagan (jlh20@rice.edu) is a postdoctoral fellow and instructor in the Program in Writing and Communication at Rice University. She has published or forthcoming articles on Blake in Configurations and the edited collection Romantic Weltliteratur of the Western World. Her current book project examines how Blake’s twentieth-century reception in American popular culture recast him as an ecological poet.

According toI would like to thank Tristanne Connolly, Joseph Campana, Claire Fanger, and the editors of this journal, Morris Eaves and Morton Paley, for their thoughtful suggestions in reading earlier versions of this article. David Erdman’s Concordance to the Writings of William Blake, the most frequently used word in Blake’s poetry is “all.”Excluding common conjunctive words like “and,” “the,” and “of.” “All” appears 1007 times—almost double the number of his second most frequently used word, “O,” which appears 555 times (Erdman, Concordance 2181). The prevalence of this pithy word suggests that radical inclusivity and interconnection are essential aspects of Blake’s thought, yet anyone familiar with his work knows that “all” cannot refer to an undifferentiated mass, because, as he makes clear, “To Generalize is to be an Idiot” (E 641). Rather, Blake continually emphasizes the importance of attention to “Minute Particulars”; as he writes in Jerusalem, “General Forms have their vitality in Particulars” (91.29, E 251). Blake’s respect for the interconnected yet sovereign identity of each and every thing resonates with recent scholarship that attempts to rethink our notions about materialism and agency. In particular, it accords with the cross-disciplinary turn to theories of the network, a form embraced in recent years for its capacity to expose otherwise hidden connections and patterns. The network form has proven especially useful to ecological theory and criticism as a nonbinary and nonanthropocentric model of description. Its advocates argue that it avoids the totalizing tendency of categorical labels like “nature” and “culture,” and that it shifts attention to the agency of individual entities, both human and nonhuman.

From Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s introduction of the rhizomatic network with the declaration “We’re tired of trees” (15) to Manuel Castells’s claim that the internet has ushered in an unparalleled epistemic revolution and Bruno Latour’s multi-book elaboration of actor-network theory (ANT), everything about recent invocations of the network screams novelty and innovation.For examples of some of the most prominent network theories, see Latour, Reassembling the Social; Galloway and Thacker; Moretti; Levine, Forms; and Jagoda. While each theory is different, all present the network as a model of nonlinear “connectivity” (Levine, Forms 112). Latour argues that networks also allow us to avoid reductive causal explanations that rely on preexisting and separate domains of reality, such as “society” or “nature,” by tracing individual points of contact or lines of influence among entities that traverse and upend such domains (Reassembling 107-10). Scholars in disciplines across the humanities and social sciences have thus turned to the network for an “exchange model” that renders visible the cross-pollination of categories normally seen as separate, without reducing one to the other.For “exchange model,” see Asprem. In “From Nation to Network,” Levine writes, “Scholars of print culture and communication and transportation have been pointing us to the importance of networks for quite some time, and the discussion has grown more vigorous recently” (656). See also Felski for a discussion of how comparative literature might benefit from network theory. Latour’s network theory emerged from science and technology studies (STS), an interdisciplinary field that draws on a wide array of disciplines, from anthropology and sociology to history and political science, and has been influential in these disciplines ever since. Critics interested in new materialisms, object-oriented philosophy, and speculative realism have been eager to embrace the network, and especially Latour’s ANT, not only for its view of actors as discrete and irreducible individuals, but also because ANT attributes agency to nonhuman, and nonliving, objects.See Harman. For a recent application of Latour, and speculative realism more broadly, to Romanticism, see Gottlieb, who devotes a chapter to each of the “big six” Romantic poets—except Blake.

Seen in the light of network theory and its relation to ecology, Blake’s preoccupation with “all” has great implications for how his work might be read differently. Despite the historicist turn to the social and material contexts in Romantic criticism, Blake critics have, for the most part, continued to nurture an exclusionary image of Blake that erects a rigid divide between the sorts of things he would have approved of and those he wouldn’t. Such exclusions are particularly evident in critical treatment of his attitude toward nonhumans and “nature,” which has received far less attention than his political and religious views, for instance.In line with ecocritical critiques of the term, I place scare quotes around the word “nature” to emphasize its unnatural status. This is owing in part to the comparatively recent development of ecocritical approaches, and in part to some of Blake’s own statements on the matter. But lines such as “I assert for My self that I do not behold the Outward Creation & that to me it is hindrance & not Action” cannot be taken unequivocally when one considers that Blake also wrote, “You certainly Mistake when you say that the Visions of Fancy are not to be found in This World” (“A Vision of the Last Judgment,” E 565; Letter to Dr. Trusler, 23 August 1799, E 702).

Blake’s Jerusalem offers a case in point for why such partial representations do Blake readers a disservice. In what follows, I delineate an incipient theory of networks in this notoriously complex text that not only anticipates our current network theories in distinct ways, but also speaks directly to the network’s implications for ecological theory and criticism. I examine Blake’s use in Jerusalem of the premodern concept of a network of correspondences, a complex and versatile idea that expresses a unifying link between all things in the universe (Faivre xxi-xxii). I argue that the network of correspondences has at least a twofold function in Jerusalem. First, it serves as a textual and iconographic figure for representing ecological interconnection, as well as Blake’s belief in the interconnection of the material and spiritual; secondly, it serves as a figure for the abuses of power enabled by this interconnection. Both functions point to the way that the figure of the network entails an implicit aspiration to represent or access a totalizing system. The desire for transcendence and omnipotence that the network form invites is ultimately denied, however, by Blake’s insistence that “all” can only be glimpsed by looking at “Minute Particulars.” As Jerusalem makes clear, “He who wishes to see a Vision; a perfect Whole / Must see it in its Minute Particulars” (91.20-21, E 251).

In what follows, I examine Blake’s representation of the network of correspondences, noting along the way its similarities to and differences from ecological criticism and recent theories of the network, especially Latour’s ANT and Alexander Galloway and Eugene Thacker’s network theory. I focus on these two theories in particular because they exemplify a celebratory and a critical view of networks, respectively. I argue that Blake, like his present-day counterparts, sees in the network a way of expressing ecological interconnection that is nonbinary, nonlinear, and radically inclusive, but that this same “flat” ontology enables and even contributes to the desire for mastery and the possibility of tyranny. In drawing out such threads, I aim to demonstrate, first, that the figure of the network provides a novel way to read Blake as an ecological poet; secondly, that Blake’s specifically ambivalent ecological vision provides useful insights into the pitfalls and assumptions of current network theories; and thirdly, that networks have a premodern dimension that prefigures applications of the network we are familiar with today.

Network Theory, Ecology, and Jerusalem’s Ambivalence

Like the city of Golgonooza, which Blake depicts as “continually building & continually decaying” (53.19, E 203), Jerusalem exhibits tendencies toward both integration and disintegration, interconnection and disconnection. Thus, while Blake critics tend to agree that Jerusalem dramatizes the consequences of division, isolation, and abstraction—Robert Essick describes it as indicative of Blake’s “desire for everything to come to a grand unity” (257) and Kevin Hutchings has called it “the most powerful instance of Blake’s critique of atomistic philosophy” (29) and a tale of Albion’s “ultimate renovation as a fully integrated, resocialized” being (156), to cite two of the more forceful pronouncements on the poem’s integrative tendency—many would also concur with Donald Ault’s assessment that the “process of integration” constituted a “crisis of vision” for Blake (173). On a formal level, as numerous critics have pointed out, Jerusalem resists its own thematic call for unity,See, for instance, Youngquist, “Reading the Apocalypse.” In The Continuing City, Paley points out that early critical interpretations of Jerusalem were united in their recognition of its “disjointedness” (27), and that Frye alone “finds it a unified whole” (26). He returns to this point later in the book, where he discusses the “disunity which all readers notice in Jerusalem” (281). For a helpful overview of critical interpretations of the poem, see Paley, Continuing City, especially 12-32 and 278-83. yet scholars have not yet connected these integrative and disintegrative impulses to the figure of the network and its implications for ecology.

To be sure, a number of scholars have drawn attention to what Jon Saklofske calls the “network architecture” of Blake’s illuminated books. Saree Makdisi notes the “wide virtual network of traces among different plates, different copies, different illuminated books” in Blake’s work (166). Roger Whitson has commented on how the “network materiality” of Blake’s work lends itself to digital platforms (46), and, more recently, Andrew Burkett has treated Blake’s “network aesthetics” in relation to media theory (98). Moreover, the work of Hutchings and Mark Lussier has already begun to dismantle the once prevalent view of Blake as an anti-nature poet—the odd man out of Romanticism.See, for instance, Hutchings, Imagining Nature; Lussier, “Blake’s Deep Ecology, or the Ethos of Otherness,” and “Blake, Deleuze, and the Emergence of Ecological Consciousness.” Michael’s article on Blake and Mary Oliver in the fall 2011 issue of this journal also stands out for its demonstration of the way that Blake’s twentieth-century reception has contributed to efforts to recast his work in a more ecological light. But none has engaged directly with both networks and ecology, and none has sought a basis for such engagement in Jerusalem.

The generality associated with the term “nature” stands as one reason Blake seemed to reject the concept outright, as he understood that universalizing claims made on behalf of “nature” tend to impose “One Law” on the multiplicity of beings (The Marriage of Heaven and Hell plate 24, E 44). As he writes in Jerusalem, for instance, “General Good is the plea of the scoundrel hypocrite & flatterer” (55.61, E 205). Hutchings has persuasively argued that Blake, perhaps more than any other Romantic poet, grasped the violence and ideological difficulties inherent in the concept of “nature”—a concept that, far from neutral, is always already implicated in human systems of power (17). Lussier and Louise Economides have separately taken up this issue of the inseparability of “nature” and human consciousness in their work on the parallels between Blake, Buddhism, and deep ecology. Lussier sees the dynamic interaction between mind and matter in Blake’s work as part of an “ethos of otherness,” or an orientation toward the other that doesn’t so much privilege human consciousness as it asks us to see that “The most sublime act is to set another before you” (“Blake’s Deep Ecology” 58; Marriage 7.17, E 36). Likewise, Lussier has pointed out that Blake’s commitment to self-annihilation intersects with both the Buddhist view of the self as the seat of suffering and our current understanding of how ecological devastation is in part a product of egoistic suffering (Romantic Dharma 180). Economides grapples with Blake’s relation to deep ecology’s dual emphasis on the “intrinsic value” of nonhuman beings, which foregrounds their irreducible alterity, and “wide identification” with nonhumans, which tends to deemphasize individual differences in favor of focusing on commonalities (par. 5). Such work has shown that Blake’s attitude toward nonhumans and the material world is, far from simply disapproving, exceedingly nuanced and complex, and avoids easy conflations of subject and object, self and other. Yet despite the inroads made by this ecocritical scholarship, Blake critics have, for the most part, remained hesitant to claim Blake for “green Romanticism” or ecological criticism more broadly.

But if Blake finds “Swelld & bloated General Forms” (Jerusalem 38 [43].19, E 185) like “nature” repugnant, the plot and tone of Jerusalem should remind us that he finds the fall into division equally abhorrent. Indeed, the poem suggests that divisions, isolation, and abstraction result from the illusion of separateness from the divine, all other beings, and even ourselves. The opening scene stages this fundamental error, as Jesus declares,

I am in you and you in me, mutual in love divine:

Fibres of love from man to man thro Albions pleasant land.

……………………………………………………

Lo! we are One

only to be met with

But the perturbed Man away turns down the valleys dark;

[Saying. We are not One: we are Many, thou most simulative]

Phantom of the over heated brain! (4.7-8, 20, 22-24, E 146)I’ve placed line 23 in italics and brackets, as Erdman does, to indicate that this line was deleted.

Each chapter in Jerusalem revolves around this tension between the One and Many, which Blake exhorts his “Giant forms” and readers alike to realize is merely a matter of perception, “for contracting our infinite senses / We behold multitude; or expanding: we behold as one” (34 [38].17-18, E 180). Jerusalem also portrays the division of the world into distinct human and nonhuman realms, and the subjugation of nonhumans implied by such a division, as harmful to humans, nonhumans, and even God: “For not one sparrow can suffer, & the whole Universe not suffer also, / In all its Regions, & its Father & Saviour not pity and weep” (25.8-9, E 170). The nonlinear, nondual, and nonanthropocentric perspective that inheres in such a statement, and in the passages quoted above, requires us to take seriously Blake’s engagement with premodern ideas about a universal network of correspondences, for I argue that it is precisely his familiarity with the notion of a network of correspondences linking the material and spiritual realms that provided him with a framework through which he could imagine “all” as interconnected and interdependent on Earth.

This notion of a network of correspondences linking all parts of the universe informs virtually every esoteric tradition, and arguably defined the Renaissance episteme.For correspondences as the Renaissance episteme, see Foucault, especially 17-45. Many of the ideas associated with the network of correspondences have also survived in present-day formulations of network theory. In Theosophy, Imagination, Tradition, Antoine Faivre defines the network of correspondences as “a matter of symbolic correspondences—but considered here as very real—between all parts of the visible and invisible universe,” and likens it to the “idea of the macrocosm and the microcosm, or principle of universal interdependence,” in which “the principles of noncontradiction and excluded third middle, as of causal linearity, are replaced by those of synchronicity and included middle” (xxi-xxii). In particular, the network of correspondences serves to draw connections between the material and spiritual realms. Likewise, we find these nonbinary, nonlinear, and radically inclusive aspects of the network of correspondences in Latour’s ANT and Galloway and Thacker’s network theory. For instance, the ability of the network of correspondences to unravel binaries accords with Galloway and Thacker’s definition of a network as “any system of interrelationality, whether biological or informatic, organic or inorganic, technical or natural—with the ultimate goal of undoing the polar restrictiveness of these pairings” (28). Even more striking is the similarity of the connections between the material and spiritual in the network of correspondences to Latour’s justification for his use of the term “network” specifically to “avoid the Cartesian divide between matter and spirit” (“On Actor-Network Theory” 370). Perhaps this similarity should not seem so surprising, considering that Latour has openly professed that actor-network theory developed out of his training in biblical exegesis (“Coming Out” 600).

Although Blake never used the phrase “network of correspondences,” his familiarity with Swedenborg, Boehme, and Paracelsus, all of whom subscribed to a theory of correspondences, in itself virtually guarantees that he would have been aware of the concept. He confirms his awareness in a direct reference to the theory of “correspondence” in his annotations to Swedenborg, where he opposes correspondence to demonstration and insists on the discreteness of corresponding domains: “Is it not also evident that one degree will not open the other & that science will not open intellect but that they are discrete & not continuous so as to explain each other except by correspondence which has nothing to do with demonstration for you cannot demonstrate one degree by the other” (E 605-06). Blake’s insistence here that each “degree” is “discrete & not continuous” relates to his views about individuality, which in turn inform his critique of atomism, as we find in a letter to George Cumberland in 1827, where he disputes Newton’s “Doctrine of the Fluxions of an Atom”: For a Line or Lineament is not formed by Chance a Line is a Line in its Minutest Subdivision[s] Strait or Crooked It is Itself & Not Intermeasurable with or by any Thing Else Such is Job but since the French Revolution Englishmen are all Intermeasurable One by Another Certainly a happy state of Agreement to which I for One do not Agree. God keep me from the Divinity of Yes & No too The Yea Nay Creeping Jesus from supposing Up & Down to be the same Thing as all Experimentalists must suppose. (E 783) Blake’s objection to atomism, like his objection to Swedenborg’s claim about demonstrating correspondences, hinges on his belief in the irreducibility of individual entities—a belief that accords with Latour’s emphasis on the irreducibility of actors in any given network, but that conflicts with Latour’s fundamental premise that a network formed by these actors could be traced and represented without violence to the individual “Minute Particulars” that constitute it. Blake’s insistence on the inscrutability of the network of correspondences to logical demonstration and the priority he grants to individuals and “Minute Particulars” represent two key critiques of the network in Jerusalem, and point to his ambivalent attitude toward networks and “natural” philosophy, not to mention Swedenborg.

His ambivalence about networks and ecology is particularly apparent in the alternately apocalyptic and unitive vision of Jerusalem. In serving as a figure for both interconnection—in an ecological sense, as well as in the sense of the interpenetration of the material and spiritual—and the abuses of power enabled by this interconnection, the network form provides an occasion to revalue Blake’s attitude toward the material world, and how his ambivalence specifically could be brought to bear on ecological theory and criticism. Rather than posing a challenge to his ecological value, Blake’s ambivalent portrayal of the network of correspondences reflects the ambivalence of existing ecological discourses, as seen, for instance, in the seemingly irresolvable tension between individual autonomy and collective action that has long hampered ecological theory and activism.

Developed in response to the global ecological crisis, ecocriticism has, since its inception, been dominated by calls for greater recognition of humanity’s interconnection with “nature.” This sentiment is epitomized by Cheryll Glotfelty’s adoption of Barry Commoner’s “first law of ecology”—the idea that “‘everything is connected to everything else’”—as a foundational principle for ecocriticism (xix), and has led ecocritics to search for new concepts, particularly concepts pertaining to our collective existence—as communities, as a species, as one form of life among others, and as a life form embedded in environments that include a host of nonliving entities. The figure of the network has emerged as a popular contender for just the sort of concept ecological theory needs, as both network theory and ecological theory destabilize broad categories like “society” and “nature” by refuting the notion that a nonhuman “nature” is somehow separate from human activity.

Others are not so certain that Commoner’s laws of ecology don’t need amending.For Commoner’s discussion of these laws, see The Closing Circle 33-46. More recently, ecological theorists have begun to recognize the limitations of a view of ecology that pays attention only to connections and harmonious relationships, since both the extent of connectedness between particular entities and the impact of particular connections vary widely, and are by no means always amicable. Frédéric Neyrat, for instance, has called for “an ecology of separation” that would recognize separation, distance, and difference as the “repressed content” of ecology (101). Thus far, however, little attention has been explicitly given to the specific ways in which network theory recapitulates and reinforces the inherent tensions and repressions of ecological thought.

These tensions become evident in the divergent attitudes toward interconnection in the network theories of Latour on the one hand and Galloway and Thacker on the other. Latour’s ANT has proven especially useful to ecological criticism, as it shares ecocriticism’s aim to deconstruct the false dichotomy between humans and “nature” and the related notion that there is a fixed distinction between conscious, active “subjects” and brute, inert “objects.” In Reassembling the Social, Latour goes about demonstrating the interpenetration of humans and nonhumans by defining the “social” not as a specific sphere or kind of thing, but rather as “a type of connection between things that are not themselves social” (5). This broadening of the meaning of “social” is central to ANT, as it exposes the diversity of entities that can and do coalesce into concretized networks. It goes hand in hand with Latour’s expansion of the meaning of “actor” to refer to quite literally “any thing” that modifies a set of circumstances, and his use of “network” to mean simply “what is traced” by following the effects of the actors linked by association (Reassembling 71, 108). ANT thus ostensibly allows anyone to trace the network of associations formed by something as basic as an atom or as complex as a nation.

In The Exploit, on the other hand, Galloway and Thacker emphasize the political, and often exploitative, implications of networked interconnection. They refer almost exclusively to technological, such as computer or informatic, networks, which for them are not so much a methodology or a thing that must be traced as a class of existing objects that are having a dramatic impact on human societies. They thus argue that networks are not as democratic as theorists such as Latour portray them (140), but rather “exercise novel forms of control that operate at a level that is anonymous and nonhuman, which is to say material” (5). The problem with networks, then, is not simply their ability to exert influence over individuals, but also the material impact of specifically “anonymous and nonhuman” forces. This becomes particularly evident in Galloway and Thacker’s discussion of the swarm, a network form that exemplifies the conflation of biological and technical networks in their work: a “swarm attacks from all directions, and intermittently but consistently,” they write, “it has no ‘front,’ no battle line, no central point of vulnerability. It is dispersed, distributed, and yet in constant communication. In short, it is a faceless foe, or a foe stripped of ‘faciality’ as such” (66). The phenomenon of swarms thus demonstrates how, above and beyond concerns about influence and control, networks conjure up anxieties about the impersonality of aggregated individuality in a collective body, and the loss of individual agency and identity that accompanies any totalizing system. As Galloway and Thacker aver, “It is the very idea of ‘the total’ that is both promised and yet continually deferred in the ‘unhumanity’ of networks, netwars, and even the multitude” (154).

While Latour’s ANT and Galloway and Thacker’s network theory are but two examples, they well represent the divide between defenders of the network, who emphasize its decentralized connectivity, attention to nonhuman agencies, and generally nonbinary nature, and critics, who point up its totalizing tendencies, anonymity, and enabling of a control society. Thus, to Latour’s claim that “dispersion, destruction, and deconstruction are not the goals to be achieved but what needs to be overcome. It’s much more important to check what are the new institutions, procedures, and concepts able to collect and to reconnect the social” (Reassembling 11), we can imagine Galloway and Thacker replying, “Connectivity is a threat. The network is a weapons system” (16). Such drastically opposed attitudes point to the extent to which the network, as the exemplary figure of interconnection in our digital age, reveals the need for a politics of interconnection. Indeed, although Galloway and Thacker’s work is also ecologically oriented, their differences with Latour rehearse a common critique of ecological discourse: that it often fails to take political questions about identity, difference, and power into account. Fortunately, these are the very sorts of topics that Blake, and Blake critics, excel at addressing. This means that historicist, formalist, and politically oriented approaches to Blake, for instance, could in fact complement ecological approaches, and, in doing so, add to his ecological value.

The alliance of these approaches with network and ecological theory is of particular relevance to Blake’s Jerusalem, an epic poem whose sheer complexity requires that we both trace connections between seemingly disparate events, characters, and formal elements and recognize how it defies such attempts at containment. On the one hand, Blake’s emphatic vision of unity, connectivity, and coexistence in Jerusalem suggests that the network form provides a useful analogue for thinking through the ontological, ethical, and political implications of his broader notion of the inseparability of the material and spiritual, and his paradoxical view of individuals as both “discrete & not continuous,” but also composed of, and a part of, other individuals. As he writes in Milton, a work often seen as continuous with Jerusalem (Hutchings 153): “We are not Individuals but States: Combinations of Individuals” (32 [35].10, E 131). Blake’s portrayal of the interconnected and interdependent relationships that inhere within a single individual reveals a symbiotic view of individuality in his work. Moreover, tracing these ideas in Jerusalem through the lens of network theory supports an ecological reading of Blake, as it reveals he had realized a basic but powerful insight: that, as ecologist Bernard Patten puts it, “ecology is networks” (343).

On the other hand, Blake’s realization that interconnection does not guarantee equality offers a corrective to ecological criticism that remains content to connect the dots between disparate entities without accounting for the dynamism and “force of things” (Bennett). As Patten also points out, the “key property of the network phenomenon is influence—cause at a distance, or indirect determination” (292). Ecological entanglement also means that no individual exists free of relations, but is rather always part of a larger system—entangled in an environment or context that threatens to exert control or undue “influence” over individuals. Thus, although Blake insists that “Contraries mutually Exist” (Jerusalem 17.33, E 162), the narrative of Jerusalem does not betray an idle acceptance of this idea, but rather continually reinscribes the tension between individual liberty and outside influence. After all, Blake more often writes of “Two bleeding Contraries equally true” or “Two Contraries War against each other in fury & blood ” (Jerusalem 24.3, E 169; 58.15, E 207; emphasis mine). But he also never backs down from his contention that only an acceptance of the coexistence of both “Contraries” will allow us to “Live in perfect harmony in Eden the land of life” (34 [38].21, E 180).

Building the “Network fine” in Jerusalem: Blake’s Dark Ecology

The word “network” appears only once throughout Blake’s work—in the third chapter of Jerusalem—but the presence and effects of networks are felt throughout the poem. In fact, the networked nature of textuality is a key feature of Blake’s texts, as Nelson Hilton has pointed out in Literal Imagination (16). The words “text” and “network” are, moreover, etymologically related, as both refer to things that are woven (OED). “Network” emerged in the sixteenth century out of the language used in metallurgy and textiles to describe objects made of fabric or metal fibers interlaced in a net or web (Levine, Forms 113). Blake’s frequent recourse to the language and imagery of both textiles and metallurgy throughout Jerusalem thus constitutes one way that he represents the network of correspondences in the poem. Indeed, to the reader attentive to the material objects in Jerusalem, the abundant looms, fibers, spindles, and webs—like the many furnaces, anvils, and descriptions of melting, forging, and molding of metals and forms—leap off the page.See plates 4, 56, 85, and 100 for examples of designs that evoke the network. A number of critics have commented on the extensive weaving imagery in Jerusalem. Erdman first noted the connection between the textile industry and the “Daughters of Albion” with their “needle work” (Prophet 332; Jerusalem 66.17, E 218). Miner and Paley have concentrated on specific aspects of this weaving theme, such as the figures of the veil and garment, respectively (Miner; Paley, “Figure of the Garment”). Hilton devotes a chapter to weaving imagery in Literal Imagination (102-26). More recently, Mazzeo has argued that the textile industry not only informed the verbal and visual content of Jerusalem, but also may have informed Blake’s very practice of illuminated printing, insofar as some of his printing techniques appear to be direct adaptations of calico printing (118). Moreover, in identifying the winged figures on plates 2, 14, and 53 as silk moths—in addition to a number of other visual allusions to silk farming scattered throughout Jerusalem—Mazzeo adds to the archive of imagery associated with textiles in the poem. These scholars also note that textile imagery crops up in other works by Blake, especially his longer works like Milton and The Four Zoas. None has noted, however, the similarities between such imagery and the language that literary critics and network theorists alike tend to use to describe networks.

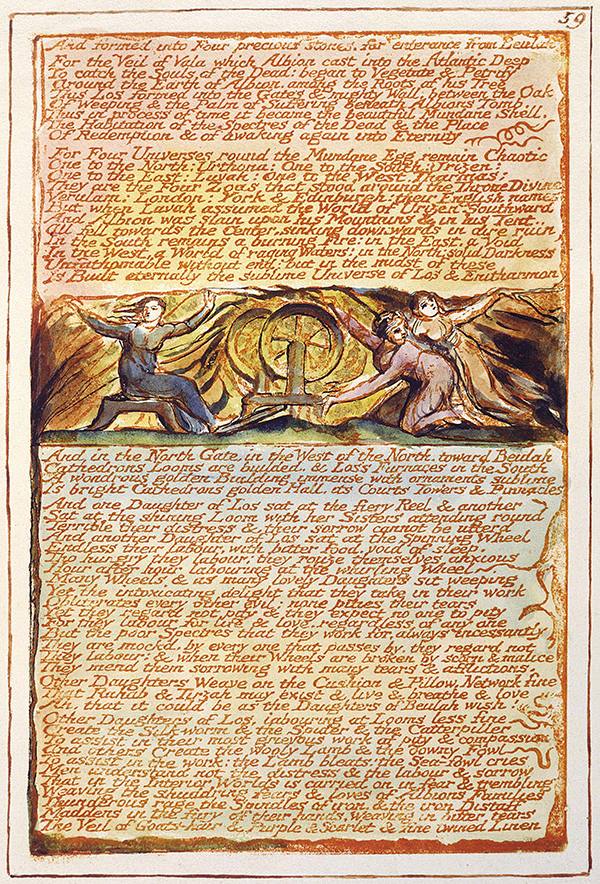

Hilton’s suggestion that Blake’s representations of networks, webs, and fibrous materials are mostly negative (107) does not square, however, with Blake’s depiction of networks in Jerusalem. It’s true that present-day network theories tend to emphasize circulation and movement, while Blake emphasizes more the mediumistic, or environmental, and entangling features of the network form. But if, for Blake, “every thing that lives is Holy” (Marriage plate 27, E 45), the network form is what enables the animation of “every thing” in Jerusalem. Both of these dynamics, the entangling and enabling, are at play in his descriptions of the weaving of the network. For instance, in his most explicit reference to a network, Blake portrays it as a medium of earthly existence characterized by breath and love: “[Los’s] Daughters Weave on the Cushion & Pillow, Network fine / That Rahab & Tirzah may exist & live & breathe & love” (59.42-43, E 209). In doing so, he casts the network as an ambient figure of environmentality—a sustaining milieu.For an analysis of the etymological links between “environment,” “ambience,” and “milieu,” see Spitzer. That he depicts the “Network fine” as an analogue to what he elsewhere calls the “Web of life” further suggests that the network in Jerusalem should be read as an ecological trope, since the web of life is a central metaphor in ecology.See, for instance, Capra. Here again, Blake’s description of this web, or network, is apparently positive, even joyful, as he writes of how Los’s “Emanation / Joy’d in the many weaving threads in bright Cathedrons Dome / Weaving the Web of life for Jerusalem” (83.71-73, E 242). His recurrent descriptions of the daughters of Albion weaving a network to link together “the Rocky Stones” (a metaphor for physical forms) with “Fibres of Life” also reinforces this double association of textiles with the network, and the network with the ecological notion of a web of life: “And the Twelve Daughters of Albion united in Rahab & Tirzah / A Double Female: and they drew out from the Rocky Stones / Fibres of Life to Weave (67.2-4, E 220).

As readers of Blake know, nothing is ever really one sided, and his use of weaving imagery here (and elsewhere) is particularly fraught. For Blake, to be woven into the web of life is as much about accepting a state of limitations, narrowed senses, mortality, and imposed order or bids for control as it is the means of communication, connection, exchange, and earthly existence. That his descriptions of the network quoted in the paragraph above feature Rahab and Tirzah specifically is another clear sign that the labor of weaving is not merely a labor of breath and love. Although Blake drew the names Rahab and Tirzah from the Bible, where they are portrayed in more or less positive terms (Sturrock 24-26), in his hands they are transformed into negative symbols of Natural Religion, and the cruelties, sacrifices, and delusions of the material world itself.See especially Jerusalem plate 67, E 220-21; 73.39, E 228; and 89.2-5, E 248. Thus, though Blake depicts Rahab and Tirzah as the origin of “Fibres of Life to Weave,” they are also described on the same plate as “denying Eternity” (67.12, E 220). As Jerusalem continually reminds us, this integrative tendency of the network is never separate from the looming threat of oppression.

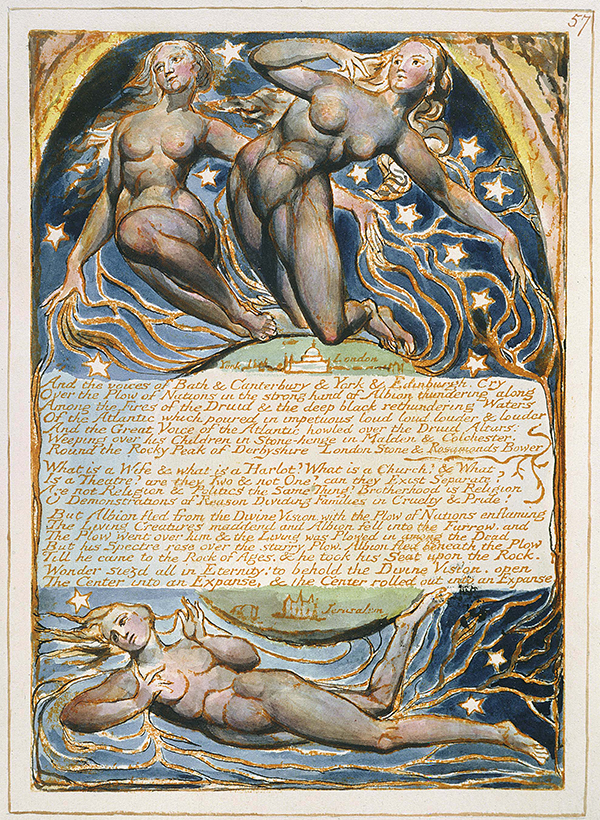

Although today the word “network” tends to evoke fiber optics more than the fibers of clothes, the etymological link between networks and textiles that is on display in Jerusalem resurfaces in Latour’s treatment of the network. Latour’s description of networks as “fibrous, thread-like, wiry, stringy, ropy, capillary” (“On Actor-Network Theory” 370), for instance, recalls the fibers, threads, and strings of Blake’s textile imagery. Moreover, his last word, “capillary,” also points to the anatomical valence of “network” and recalls the correspondence between the network of veins and arteries in the body and the network crisscrossing the globe that we find in the relation between the design on plate 57 and the textual description on plate 83. Tracing this relationship demonstrates how the network also manifests in Jerusalem as a complex and nonlinear constellation of relations that link distinct plates, various scales, and different dimensions all at once.

Let Cambel and her Sisters sit within the Mundane Shell:

Forming the fluctuating Globe according to their will.

According as they weave the little embryon nerves & veins

The Eye, the little Nostrils, & the delicate Tongue & Ears

Of labyrinthine intricacy: so shall they fold the World

That whatever is seen upon the Mundane Shell, the same

Be seen upon the Fluctuating Earth woven by the Sisters. (83.32-39, E 241) Not only does this description of Cambel and her sisters sitting “within the Mundane Shell: / Forming the fluctuating Globe” fit the image on plate 57 of three women in the act of covering Earth with a network of “embryon nerves & veins,” but the imagery of being “Immingled, interwoven” also evokes the entanglements and textiles associated with the term “network.” As Latour’s description of networks as “capillary” suggests and as Blake’s anatomical language here confirms, “network” also has a biological sense that refers to a structure with intersecting lines or interstices “forming part of animal or plant tissue” (OED). Whereas in the image we see this network at a scale “above,” or greater than, that of Earth, in the text it appears “below” the surface of the human body, on the anatomical scale of “nerves & veins.” Moreover, another layer of connection inheres in the network of correspondences between “whatever is seen upon the Mundane Shell” and what is “seen upon the Fluctuating Earth woven by the Sisters.” The network thus acts as a bridge between widely divergent scales, linking separate chapters and plates, and highlighting the “network architecture” of Blake’s poem.

Indeed, the scale of action in Jerusalem ranges from the cosmic to minute, from the infinite to the infinitesimal, in a way that gestures toward the constitutive role that networks play in an array of contexts. This fractal quality of the network—its scalability and the self-similarity among the various scales—also surfaces in more recent theorizations. In the final pages of The Exploit, Galloway and Thacker call this quality the “elemental” nature of networks: Networks are elemental, in the sense that their dynamics operate at levels ‘above’ and ‘below’ that of the human subject. The elemental is this ambient aspect of networks, this environmental aspect—all the things that we as individuated human subjects or groups do not directly control or manipulate. The elemental is not ‘the natural,’ however (a concept that we do not understand). The elemental concerns the variables and variability of scaling, from the micro level to the macro. (157) Galloway and Thacker associate this notion of the elemental with “an ancient, even pre-Socratic understanding of networks. The pre-Socratic question is a question about the fabric of the world. Of what is it made? What is it that stitches the world together, that links part to part in a larger whole?” (156). Their language recalls the language of networks that we find in Blake and in Faivre’s description of the network of correspondences. For instance, “the fabric of the world,” or that which “stitches the world together” recalls Blake’s portrayal of the network as an eminently scalable medium of existence—a “Network fine” that appears at once on the micro level of “the little embryon nerves & veins” and on the macro level as the “threads of Vala & Jerusalem running from mountain to mountain / Over the whole Earth” (67.28-29, E 220)—while their claim that networks “operate at levels ‘above’ and ‘below,’” “from the micro level to the macro,” clearly echoes the “idea of the macrocosm and the microcosm, or principle of universal interdependence” that Faivre associates with the network of correspondences. These verbal parallels provide an opening to read Blake’s preoccupation with “variables and variability of scaling” as a concern with the “elemental,” and to connect this interest to the ecocritical turn to the elemental. This elemental turn, which Jeffrey Jerome Cohen and Lowell Duckert describe in Elemental Ecocriticism as seeking to recover a view of matter as a “precarious system and dynamic entity” rather than a “reservoir of tractable commodities” (5), calls attention to the ways that the material elements themselves have agency.

A focus on the “inhuman challenge” of the elemental can also activate fears about the potential loss of individuality and control associated with networks and ecological entanglement (Cohen and Duckert 6). It is this attention to the dangers of connectivity and corporatism that we tend to associate with Blake, and Jerusalem certainly provides a wealth of examples that demonstrate how attempts to assert or regain one’s autonomy can quickly escalate into ploys to gain dominion. Likewise, Blake shows how the same network of correspondences that represents a means of connection and intimacy can double as a tool of tyranny and war. For instance, when Los complains that he will soon be “overgrown in roots,” and directs his emanation, Enitharmon, to “draw out in pity” the “fibres” surrounding him and “let them run on the winds of thy bosom” (87.6, 8-9, E 246), she retorts:

No! I will sieze thy Fibres & weave

Them: not as thou wilt but as I will, for I will Create

A round Womb beneath my bosom lest I also be overwoven

With Love; be thou assured I never will be thy slave

Let Mans delight be Love; but Womans delight be Pride

In Eden our loves were the same here they are opposite

I have Loves of my own. (87.12-18, E 246)

Here, we see how “Fibres of Brotherhood,” or interconnection, can be placed in the service of “Fibres of dominion” (88.14, 13, E 246). This image of two beings linked by “Fibres,” with both vying for control in increasingly grandiose ways, demonstrates how actions rooted in self-interest can play into the hands of instrumental reason and social control, potentially devolving into violence and tyranny. Enitharmon’s reaction to Los’s desire for independence—her decision to fight fire with fire by responding to Los’s desire with her own assertions of independence—goes on to provoke Los, on the next plate, to act in even more destructive and dictatorial ways. Together, their interaction dramatizes the darker side of ecological or networked interconnection, as it not only shows how changes in one part of a networked or ecological system can create feedback loops that worsen the conditions of the system as a whole, but also demonstrates how networked and ecological interconnection can paradoxically lead to or deepen divisions.

Galloway and Thacker appear to have recognized Blake’s insight on this matter, as their admonition that “there exists today a fearful new symmetry of networks fighting networks” (15) points directly back to Blake. “Fearful new symmetry” at once alludes to how our increasingly networked world entails ever-higher levels of risk and raises the question of whether equality, or “symmetry,” in power relations is in fact always desirable. Like the passage featuring Los and Enitharmon discussed in the previous paragraph, Galloway and Thacker’s line harnesses Blake’s ambivalence toward “fearful symmetry” and helps to explain their and Blake’s hesitance toward networked and ecological interconnection.

To understand how the framework of the network adds to this Blakean insight, we need only turn to the figure of the Polypus in Jerusalem, which not only could be usefully compared to Galloway and Thacker’s discussion of swarms and faceless enemies, but also illuminates how this “fearful new symmetry” relates to Blake’s view of individuals as both discrete and yet constituted of and entangled with other individuals.

Envying stood the enormous Form at variance with Itself

In all its Members: in eternal torment of love & jealousy:

Drivn forth by Los time after time from Albions cliffy shore,

Drawing the free loves of Jerusalem into infernal bondage;

That they might be born in contentions of Chastity & in

Deadly Hate between Leah & Rachel, Daughters of Deceit & Fraud

Bearing the Images of various Species of Contention

And Jealousy & Abhorrence & Revenge & deadly Murder. (69.6-13, E 223)

Blake’s depiction of the Polypus, a form that he describes in the lines before these as “all the Males combined into One Male” such that “every one / Became a ravening eating Cancer growing in the Female” (69.1-2, E 223), suggests that any “enormous Form” that purports to encompass “all” can only do so with extreme violence. Anything that connects and thus affects “all” will have to contend with the conflicts that inevitably arise from the vagaries of individual desires, agencies, and bids for control—many of which oppose each other (and even themselves). Here, Blake rejects the illusion of harmony in any form of holism, and reminds us why, if the other Romantics enjoin us to idealize a vast and grand image of “nature”—“the one life within us and abroad” (Coleridge 28)—he prefers a “nature” of the minute and particular. Much like Galloway and Thacker’s description of swarms, not only does the formation of the Polypus involve “Jealousy & Abhorrence & Revenge & deadly Murder,” such a conglomerate form makes it nearly impossible to determine who is to blame, and even what constitutes an action (Stout 3). As Daniel Stout argues in regard to a new awareness in the Romantic period of the networks of information and affect that bind us together, “It may be that all action can be said to begin in self-interest,” but “no action can be said to stay that way” (4).

In this light, the many lists of objects and proper names in Jerusalem, which have memorably been described as a “wall of words” (De Luca 89), form a counterpoint to the aggregated and anonymous form of the Polypus. For instance, when, in a more metallurgical than textile depiction of the network that enables existence, Blake describes Los’s furnaces, anvil, and hammer in the process of creating life on earth, he does so by listing specific parts of the ecosystem: “howl[ing] loud; living: self-moving,” they range across the four corners of the Earth “To Create the lion & wolf the bear: the tyger & ounce: / To Create the wooly lamb & downy fowl & scaly serpent / The summer & winter: day & night: the sun & moon & stars / The tree: the plant: the flower: the rock: the stone: the metal” (73.2, 17-20, E 228). Blake’s frequent use of catalogues and his habit of using ampersands and colons to separate the terms within them have the effect of at once visually and verbally distinguishing these entities from one another and suggesting their likeness or analogy with one another. This combination of conjunction and distinction in Blake’s catalogues recalls Latour’s predilection for making lists—“Latour litanies” (Bogost 38)—and confirms object-oriented critics’ sense of the list as a useful ecological trope.See Morton, “Here Comes Everything” 173; Bogost 49-59.

Another way that Blake addresses the dangers of generalization is purposefully to avoid representing “all” at once. This is particularly evident in his visual depictions of network imagery, which figure prominently in the designs of Jerusalem. For example, consider the three women shown in the act of weaving on plate 59, the same plate on which Blake’s single instance of the word “network” appears.

In light of Blake’s refusal to concede to such claims to mastery, it is worth taking stock of the instances in which he admits to his own dependencies and limitations. Indeed, although critics have paid little attention to how Blake was influenced by nonhuman, material entities,A few exceptions come to mind. Fosso, Perkins, and Patenaude, for example, have examined the role of nonhuman animals in Blake’s work, and, in Patenaude’s case, geographical features as well, while Viscomi has treated Blake’s awareness of the important role of the materiality of his medium and artistic tools in his work (see especially Viscomi 40-50). many have been more willing to take seriously the idea that he was subject to the dictates of spiritual beings. Jerusalem begins on such a note, as Blake writes in the preface to the first chapter: “We who dwell on Earth can do nothing of ourselves, every thing is conducted by Spirits, no less than Digestion or Sleep” (E 145). Other instances drawn from his letters confirm this sense of Blake as very much aware of his own submission to such spiritual dictates, as when he writes to Thomas Butts: “I am under the direction of Messengers from Heaven Daily & Nightly but the nature of such things is not as some suppose. without trouble or care. Temptations are on the right hand & left behind the sea of time & space roars & follows swiftly he who keeps not right onward is lost & if our footsteps slide in clay how can we do otherwise than fear & tremble” (10 January 1803, E 724). In addition to its connection to theories of the network, Blake’s awareness of his entanglement with material and spiritual beings accords with the notion of “trans-corporeality” developed by ecocritic Stacy Alaimo, which exposes how humans are always already entangled with nonhumans. “Since ‘nature’ is always as close as one’s own skin—perhaps even closer,” she writes, “thinking across bodies may catalyze the recognition that the environment, which is too often imagined as inert, empty space or as a resource for human use, is, in fact, a world of fleshy beings with their own needs, claims, and actions” (2). Alphonso Lingis delineates those “needs, claims, and actions” in The Imperative, where his central premise is that “sensibility, sensuality, and perception [are] not reactions to physical causality nor adjustments to physical pressures, nor free and spontaneous impositions of order on amorphous data, but responses to directives” issued by the things in and of our environment (3)—a claim analogous to the basic idea underlying ANT, and one that has resonated with ecocritics and scholars interested in the new materialisms. Lingis’s notion of “responses to directives” provides an illuminating parallel to Blake’s descriptions of being “under the direction of Messengers” and “conducted by Spirits,” as it draws out the environmental, or atmospheric, connotations of the word “spirit” and allows us to see Blake’s statements as evidence of his environmental awareness and responsivity.

Thus Blake, and Jerusalem in particular, have much to say about the importance of inclusion and relations with other, nonhuman beings. Against the subject/object dualism implied by a mechanistic concept of “nature,” Blake’s representation of the network of correspondences in Jerusalem evinces his belief in the importance of the “minute particulars” of each individual actor, as well as an essential unity linking all kinds of beings, both spiritual and earthly. In the last lines, he posits a unity predicated on the shared divinity of all things:

All Human Forms identified even Tree Metal Earth & Stone. all

Human Forms identified, living going forth & returning wearied

Into the Planetary lives of Years Months Days & Hours reposing

And then Awaking into his Bosom in the Life of Immortality.

And I heard the Name of their Emanations they are named Jerusalem.

(99.1-5, E 258-59)

Although this passage would seem to confirm the sentiment that the “only valid generalization one can make about Blake’s overall attitude toward nature is that he almost never treats it apart from a human context” (Lefcowitz 121), Blake’s anthropomorphism here actually confers on all beings the powers normally reserved for “Human Forms.” For Blake, a “Human Form” is one with a will, individual perspective, and the faculty of imagination. To say that trees, metal, earth, and stones are “Human Forms” is to say that they have their own kind of intelligence, point of view, and power in the world. Rather than subjecting “nature,” Blake endows both human and nonhuman entities with intrinsic value and agency in Jerusalem. He is not so much opposed to nonhumans or the “unhumanity” of networks, then, as he is to the inhumane.Hutchings makes a similar point in the coda to Imagining Nature about humanization being a process aimed at humans’ “anything but humane” treatment of nonhumans and other humans (217; see also 206-09).

Network Form and Its Consequences

The title of this concluding section is a reference to Frances Ferguson’s essay “Organic Form and Its Consequences.” Therein, Ferguson traces how the notion of organic form as a kind of model object developed in the Romantic period into an organicist method, and how this organicism paradoxically led to a kind of mechanistic utilitarianism, in which descriptions of the particularities of unique objects are given up for the application of generalizing and universalizing assumptions (232). It is this understanding of utilitarianism—not anything like “nature” or any individual organic or inorganic entities—Ferguson argues, that emphasized “the importance of environment in understanding what it was to make a choice” (234); that is, for figures such as Bentham and Hume, who epitomize this sort of “classical utilitarianism,” the making of a choice is not an assertion of belief or an exercise of self-interest, but merely a response to the narrowed range of options defined by one’s context or environment (234-35). In this utilitarian view, choices do not have to be conscious; they become “virtually automatic rather than expressive of free will or large-scale belief” (235).

I mention this essay because it seems to me to provide an analogue to how, though it may not strike us as an organic metaphor, the network form constitutes a type of organicism akin to the mechanistic utilitarianism that Ferguson describes—that is, in the network theories explored in my essay, the network is imagined either, as in Latour’s ANT, as an abstract and effectively universal concept, or, as in Galloway and Thacker’s networks, as a “faceless” whole greater than the sum of its parts. Both end up conveying more of the “Mystery” of networks than confidence in their transparency. Here, I use the word “Mystery” with its specifically Blakean inflections: “Mystery” as that which obfuscates and disempowers, “Mystery” as that which exploits the mystified.The word “Mystery” (often, the “tree,” “root,” or “stem” of Mystery) appears throughout Blake’s work, beginning with the Songs, and with greater frequency in Jerusalem and especially The Four Zoas. In addition to its association with obscurity and exploitation, its close and frequent connection with vegetative imagery suggests that Blake also associates “Mystery” with the deceptions of natural religion, and with claims made on behalf of “nature” more generally. See “The Human Abstract” (E 27); Jerusalem (75.19, E 231; 83.13, E 241; 93.25, E 254); and the numerous instances in The Four Zoas. In short, like Blake’s notion of “Mystery,” both network theories end up suggesting that to recognize that we live in an age of networks is to recognize how little we, as individuals, matter. Indeed, Blake understood that networks, in standing in for things we cannot fully conceptualize or accurately map, risk reinscribing “Priesthood” by another name.The context of Blake’s use of the term “Priesthood” in Marriage is also instructive, and clarifies the term’s connection to “Mystery”: “Till a system was formed, which some took advantage of & enslav’d the vulgar by attempting to realize or abstract the mental deities from their objects: thus began Priesthood” (plate 11, E 38).

Only genuine ambivalence, it seems, comes close to abiding with the complexity that networks, ecological or otherwise, present, and it is precisely Blake’s ambivalence toward networks in Jerusalem that make the poem such a fitting text for understanding the impasses in both ecological and network theory. As we’ve seen, network theory can help us recognize the many examples of nonhuman agency at work in Jerusalem, as in the active roles played by nonhumans in the recurrent battles that break out over the rightful possessors of Albion, Jerusalem, and their emanations:

Loud! loud! the Mountains lifted up their voices, loud the Forests

Rivers thunderd against their banks, loud Winds furious fought

Cities & Nations contended in fires & clouds & tempests.

The Seas raisd up their voices & lifted their hands on high

The Stars in their courses fought. the Sun! Moon! Heaven! Earth.

Contending for Albion & for Jerusalem his Emanation

And for Shiloh, the Emanation of France & for lovely Vala. (55.23-29, E 204)

Scenes such as this, which emphasize the formidable sublimity of nonhumans’ power, challenge the assumption of Blake’s belief in humans’ mastery over the nonhuman world. In fact, Jerusalem depicts nonhumans rejecting human attempts to gain control: “They send the Dove & Raven: & in vain the Serpent over the mountains. / And in vain the Eagle & Lion over the four-fold wilderness. / They return not: but generate in rocky places desolate. / They return not; but build a habitation separate from Man” (66.70-73, E 219). Blake’s implicit attribution of agency to discrete nonhuman actors in such passages, though not without ambivalence, anticipates ANT’s attention to how, more than a mere backdrop to human action, nonhumans “authorize, allow, afford, encourage, permit, suggest, influence, block, render possible, [and] forbid” human action, and thus exercise agency in their own right (Latour, Reassembling 72).

Galloway and Thacker’s network theory and Jerusalem have also been mutually illuminating, especially in regard to Blake’s crisis of integration. Galloway and Thacker’s insight that “it is the very idea of ‘the total’ that is both promised and yet continually deferred in the ‘unhumanity’ of networks, netwars, and even the multitude,” calls attention to the way that Blake depicts totalizing gestures and figures in the poem as totalitarian—and self-defeating. As he writes in his address “To the Jews”: “And he who makes his law a curse, / By his own law shall surely die” (27.83-84, E 173). On the other hand, if the many sudden bodily “Divisions and Comminglings” in Jerusalem are any indication, Blake remains more open to the veering agencies and alliances—human, nonhuman, and spiritual—that surprise and upset Galloway and Thacker’s almost technological determinist account of networks.For “Divisions and Comminglings,” see Connolly, especially chapters 5 and 6. It is for this reason that Blake forecloses on the possibility of seeing “all,” and instead tends to rely on the catalogue as a mode of nontotalizing inclusivity.

My reading of the various representations of the network in Jerusalem thus suggests that Blake’s ecology is best understood as a dark ecology. Morton’s notion of a “dark ecology” proposes that “instead of perpetuating metaphors of depth and authenticity (as in deep ecology), we might aim for something profound yet ironic, neither nihilistic nor solipsistic, but aware like a character in a noir movie of her or his entanglement in and with life-forms” (“Queer Ecology” 279). The darkness of this dark ecology refers both to its openness to a universe of withdrawn beings—a “nature” that exceeds human comprehension—and to the epistemological and ethical implications of such a view.

As ecocritics have recently begun to argue, although the ecological crisis has required that we rethink our collective existence, it has also made thinking a whole, totality, or world—anything like a notion of “all”—nearly impossible. Timothy Clark, for example, has critiqued a number of well-meaning but problematic ecological narratives that convey a sense that “reality itself is ‘continuous,’” such as the “whole earth” discourse that arose in the 1960s with NASA’s photographs of Earth from space (17). Clark’s point is that “the earth is not ‘one’ in the sense of an entity we can see, understand or read as a whole”; rather, we always perceive Earth from “inside” it (15). Morton’s dark ecology and Clark’s critique of the desire for a totalizing view dovetail with the critiques of reductionism, absolutes, and holism that we find in Blake’s Jerusalem, as well as his broader disdain for generalization and tyranny. Indeed, Blake’s own depiction of Earth from outer space on plate 57 of Jerusalem purposefully refuses to provide us with a complete image of the globe.

What, then, do Blake’s continual recourse to “all” and his use of network imagery mean in light of such critiques, considering the close associations between networks and totalities? Jerusalem suggests that he invokes words like “all” and the concept and imagery of the network to figure a mode of inclusivity and collectivity that can never be grasped “all” at once, as Los reminds us: “And [Los] saw every Minute Particular of Albion degraded & murderd / But saw not by whom; they were hidden within the minute particulars” (45 [31].7-8, E 194). Blake’s deployment and critique of the network of correspondences suggests that current interest in the network stems from the way that it tends to function as a placeholder for things we do not, and perhaps cannot, understand—one of which is how we could be both individual and composite entities at the same time. Learning how to accept, if not understand, such ideas is the desiderata of ecological criticism, too, as Val Plumwood argues in Environmental Culture: The Ecological Crisis of Reason: “We need a concept of the other as interconnected with self, but as also a separate being in their own right, accepting the ‘uncontrollable, tenaciousness otherness’ of the world as a condition of freedom and identity for both self and other” (201). Indeed, the other side of Blake’s insistence on “all” is his dictum that “The Infinite alone resides in Definite & Determinate Identity” (Jerusalem 55.64, E 205). Just as he here locates the Infinite in the Definite, Blake often makes statements that appear or explicitly are contradictory. “Blake’s theology,” Mark Trevor Smith explains, “is inconsistent and anti-rational because he is pursuing the details of the world, full of life and therefore of oppositions” (203). Against holism and reductionism, then, we would do well to follow Blake when he writes: “Labour well the Minute Particulars, attend to the Little-ones: / And those who are in misery cannot remain so long / If we do but our duty: labour well the teeming Earth” (Jerusalem 55.51-53, E 205).

Works Cited

Alaimo, Stacy. Bodily Natures: Science, Environment, and the Material Self. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010.

Asprem, Egil. “Dis/unity of Knowledge: Models for the Study of Modern Esotericism and Science.” Numen 62.5-6 (2015): 538-67.

Ault, Donald D. Visionary Physics: Blake’s Response to Newton. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974.

Bennett, Jane. “The Force of Things: Steps toward an Ecology of Matter.” Political Theory 32.3 (2004): 347-72.

Blake, William. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. Ed. David V. Erdman. Rev. ed. New York: Anchor, 1988.

Bloom, Harold. Blake’s Apocalypse: A Study in Poetic Argument. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1963.

Bogost, Ian. Alien Phenomenology, or What It’s Like to Be a Thing. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Burkett, Andrew. “Blake’s Moving Images.” Romantic Mediations: Media Theory and British Romanticism. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2016. 75-114.

Capra, Fritjof. The Web of Life: A New Scientific Understanding of Living Systems. New York: Anchor, 1996.

Castells, Manuel. The Rise of the Network Society. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1996.

Clark, Timothy. “What on World Is the Earth?: The Anthropocene and Fictions of the World.” Oxford Literary Review 35.1 (2013): 5-24.

Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome, and Lowell Duckert, eds. Elemental Ecocriticism: Thinking with Earth, Air, Water, and Fire. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. The Major Works. Ed. H. J. Jackson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Commoner, Barry. The Closing Circle: Nature, Man, and Technology. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1971.

Connolly, Tristanne J. William Blake and the Body. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

De Luca, Vincent. Words of Eternity: Blake and the Poetics of the Sublime. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991.

Economides, Louise. “Blake, Heidegger, Buddhism, and Deep Ecology: A Fourfold Perspective on Humanity’s Relationship to Nature.” Romanticism and Buddhism. Ed. Mark Lussier. Romantic Circles Praxis Series. February 2007. 17 pars.

Erdman, David V. Blake: Prophet against Empire. 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969.

Erdman, David V., ed., with the assistance of John E. Thiesmeyer, Richard J. Wolfe, et al. A Concordance to the Writings of William Blake. 2 vols. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1967.

Essick, Robert N. “Jerusalem and Blake’s Final Works.” The Cambridge Companion to William Blake. Ed. Morris Eaves. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. 251-71.

Faivre, Antoine. Theosophy, Imagination, Tradition: Studies in Western Esotericism. Trans. Christine Rhone. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2000.

Felski, Rita. “Comparison and Translation: A Perspective from Actor-Network Theory.” Comparative Literature Studies 53.4 (2016): 747-65.

Ferguson, Frances. “Organic Form and Its Consequences.” Land, Nation and Culture, 1740–1840: Thinking the Republic of Taste. Ed. Peter de Bolla, Nigel Leask, and David Simpson. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. 223-40.

Fosso, Kurt. “‘Feet of Beasts’: Tracking the Animal in Blake.” European Romantic Review 25.2 (2014): 113-38.

Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. New York: Vintage Books, 1994.

Frye, Northrop. Fearful Symmetry: A Study of William Blake. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1947.

Galloway, Alexander R., and Eugene Thacker. The Exploit: A Theory of Networks. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

Glotfelty, Cheryll. “Introduction: Literary Studies in an Age of Environmental Crisis.” The Ecocriticism Reader: Landmarks in Literary Ecology. Ed. Glotfelty and Harold Fromm. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1996. xv-xxxvii.

Gottlieb, Evan. Romantic Realities: Speculative Realism and British Romanticism. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016.

Harman, Graham. Prince of Networks: Bruno Latour and Metaphysics. Melbourne: re.press, 2009.

Hilton, Nelson. Literal Imagination: Blake’s Vision of Words. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983.

Hutchings, Kevin. Imagining Nature: Blake’s Environmental Poetics. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2002.

Jagoda, Patrick. Network Aesthetics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Latour, Bruno. “Coming Out as a Philosopher.” Social Studies of Science 40.4 (2010): 599-608.

———. “On Actor-Network Theory: A Few Clarifications.” Soziale Welt 47.4 (1996): 369-81.

———. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Lefcowitz, Barbara F. “Blake and the Natural World.” PMLA 89.1 (January 1974): 121-31.

Levine, Caroline. Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

———. “From Nation to Network.” Victorian Studies 55.4 (summer 2013): 647-66.

Lingis, Alphonso. The Imperative. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998.

Lussier, Mark. “Blake, Deleuze, and the Emergence of Ecological Consciousness.” Ecocritical Theory: New European Approaches. Ed. Axel Goodbody and Kate Rigby. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2011. 256-69.

———. “Blake’s Deep Ecology, or the Ethos of Otherness.” Romantic Dynamics: The Poetics of Physicality. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000. 47-63.

———. Romantic Dharma: The Emergence of Buddhism into Nineteenth-Century Europe. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Makdisi, Saree. William Blake and the Impossible History of the 1790s. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

Mazzeo, Tilar J. “William Blake’s Golden String: Jerusalem and the London Textile Industry.” Studies in Romanticism 52.1 (spring 2013): 115-45.

Mee, Jon. Dangerous Enthusiasm: William Blake and the Culture of Radicalism in the 1790s. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992.

Michael, Jennifer Davis. “Eternity in the Moment: William Blake and Mary Oliver.” Blake 45.2 (fall 2011): 44-50.

Miner, Paul. “William Blake: Two Notes on Sources.” Bulletin of the New York Public Library 62 (1958): 203-07.

Moretti, Franco. “Network Theory, Plot Analysis.” Pamphlets of the Stanford Literary Lab. 1 May 2011. <http://litlab.stanford.edu/LiteraryLabPamphlet2A.Text.pdf>.

Morton, Timothy. “Here Comes Everything: The Promise of Object-Oriented Ontology.” Qui Parle 19.2 (2011): 163-90.

———. “Queer Ecology.” PMLA 125.2 (March 2010): 273-82.

“network, n. and adj.” Oxford English Dictionary. June 2017. <https://www.oed.com>.

Neyrat, Frédéric. “Elements for an Ecology of Separation: Beyond Ecological Constructivism.” General Ecology: The New Ecological Paradigm. Ed. Erich Hörl with James Burton. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 101-27.

Paley, Morton D. The Continuing City: William Blake’s “Jerusalem.” Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1983.

———. “The Figure of the Garment in The Four Zoas, Milton, and Jerusalem.” Blake’s Sublime Allegory: Essays on “The Four Zoas,” “Milton,” “Jerusalem.” Ed. Stuart Curran and Joseph Anthony Wittreich, Jr. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1973. 119-39.

Patenaude, Troy. “‘nourished by the spirits of forests and floods’: Blake, Nature, and Modern Environmentalism.” Re-envisioning Blake. Ed. Mark Crosby, Patenaude, and Angus Whitehead. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. 180-206.

Patten, B. C. “Network Ecology: Indirect Determination of the Life-Environment Relationship in Ecosystems.” Theoretical Studies of Ecosystems: The Network Perspective. Ed. M. Higashi and T. P. Burns. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. 288-351.

Perkins, David. “Animal Rights and ‘Auguries of Innocence.’” Blake 33.1 (summer 1999): 4-11.

Plumwood, Val. Environmental Culture: The Ecological Crisis of Reason. Abingdon: Routledge, 2002.

Saklofske, Jon. “Remediating William Blake: Unbinding the Network Architectures of Blake’s Songs.” European Romantic Review 22.3 (June 2011): 381-88.

Smith, Mark Trevor. ‘All Nature Is But Art’: The Coincidence of Opposites in English Romantic Literature. West Cornwall, CT: Locust Hill Press, 1993.

Spitzer, Leo. “Milieu and Ambiance: An Essay in Historical Semantics.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 3.1 (September 1942): 1-42, and 3.2 (December 1942): 169-218.

Stout, Daniel M. Corporate Romanticism: Liberalism, Justice, and the Novel. New York: Fordham University Press, 2017.

Sturrock, June. “Blake and the Women of the Bible.” Literature and Theology 6.1 (March 1992): 22-32.

“text, n.1.” Oxford English Dictionary. June 2017. <https://www.oed.com>.

Viscomi, Joseph. Blake and the Idea of the Book. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Whitson, Roger. “Digital Blake 2.0.” Blake 2.0: William Blake in Twentieth-Century Art, Music and Culture. Ed. Steve Clark, Tristanne Connolly, and Jason Whittaker. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. 41-55.

Youngquist, Paul. Madness and Blake’s Myth. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1989.

———. “Reading the Apocalypse: The Narrativity of Blake’s Jerusalem.” Studies in Romanticism 32.4 (winter 1993): 601-25.