Blake, Paul, and Sexual Antinomianism

Christopher Z. Hobson (hobsonc@oldwestbury.edu), professor of English at SUNY Old Westbury, is the author of The Chained Boy: Orc and Blake’s Idea of Revolution, Blake and Homosexuality, and, most recently, James Baldwin and the Heavenly City: Prophecy, Apocalypse, and Doubt.

Because the soul of sweet delight can never be defil’d. (America 8.13-14)

This essay considers the biblical contexts for the genesis, elaboration, and later reworking of what can be called Blake’s sexual antinomianism—his view of the body, genitals, and sexual love as holy, in opposition to moral law. These contexts, and Blake’s sexual antinomianism generally, are surprisingly underdiscussed; in recent decades, religious influences on Blake’s antinomianism more often have been treated through seventeenth- and eighteenth-century parallels and with regard to other issues. Here I propose that the development of Blake’s ideas on sexuality and moral law centers on a sustained appropriative and revisionary, sometimes polemical, engagement with biblical texts, particularly St. Paul’s teachings on the body and moral conduct, and that this development can be traced through several texts that interact both with one another and directly or implicitly with Paul. The three key texts in my discussion are “The Divine Image” (especially line 11); America 8.10-14, whose “every thing that lives is holy” formula—with its iterations in several other works—acts to link my chosen texts to one another; and The Everlasting Gospel section f, “Was Jesus Chaste.” Together these outline a series of attitudes that, despite some affinities to contemporaries and precursors, form a distinct, recognizably Blakean mix that persists in his later work but, I argue, is modified to allow for humanity’s deep imperfection in the state he calls Generation.

There are two reasons for thinking Paul may be particularly significant in understanding Blake’s view of bodily holiness. First, parallels between Blake and religious traditions such as seventeenth-century antinomianism and contemporaneous Moravianism provide only general and partial resemblances and in any case do not reveal the particular logic by which Blake works out his ideas.For example, major elements of Moravian worship are unknown or distinct in Blake (Rix 9), including sexual fetishization of Christ’s wounds and a substitutionary view of atonement (Christ pays the penalty for sin; compare Blake’s “Offering of Self for Another” in “Brotherhood,” Jerusalem 96.21). See below for some divergences between Blake’s ideas and those of Abiezer Coppe, often considered an antinomian forerunner. Similar suggestions have been made for Jacob Bauthumley (Makdisi 250, noted below; Thompson 26, 27, 41), Laurence Clarkson (especially Makdisi 95, 97), John Saltmarsh (Mee 61), and others; see Mee’s useful point that antinomianism should be considered “[not] so much a specific heresy as a tendency” (59). On Moravianism, see extensive writings by Keri Davies, Marsha Keith Schuchard, and the two together. In doing so, he is likely to have relied on his overall practice of using and rethinking biblical materials; for issues of the body, sexuality, and sexual conduct, Paul is the most relevant biblical source.

More broadly, Paul is a key reference for the overall antinomianism many observers find in Blake.See Davies and Worrall 44-46 for a dissent, though limited to the term’s applicability to Moravian doctrine and without discussion of Blake’s texts or art. Moreover, Davies and Worrall do not refer to eighteenth-century opinions (notably Wesley’s and in part Whitefield’s) that did regard Moravianism as quasi-antinomian (see, for example, Coppedge 45-49 and Dallimore 324-32). In a book-length treatment, Jeanne Moskal argues that Blake at first embraces antinomian rejection of the law, but that this rejection is self-limiting in that it remains logically dependent on the law it tries to reject. Moskal believes that later Blake, in a “sequential” or “successive” stage in his thinking (9, 10), supersedes antinomianism by basing forgiveness mainly on an interior ethics of “virtue” or “dispositions” and an interpersonal “ethics of care and alterity” (3, 7). Her division of stages is misleading both because Blake continues to attack law and moral strictures in later work and, more fundamentally, because we remain under the law’s domination, so that rejecting law remains a necessary part of Blake’s thought. In Blake and the Bible, Christopher Rowland proposes that “Blake’s antipathy to devotion to a bible or sacred code has its origins in the Pauline corpus,” and that Blake shared Paul’s belief that with Christ’s coming “the dispensation of the Law is past” (215). Rowland further finds in both an emphasis on “indwelling spirit” and the importance of “visionary experience” (200-01). Finally, he notes Blake’s investment, despite differences, in Paul’s idea of the collective body of Christ and the “space opened up by the divine life in Christ as an arena for epistemological and ethical transformation” (214-15; see also Rose, especially 406). Of the differences between Blake and Paul, the most important for my discussion is what Rowland sees as Blake’s “inclusive” rather than exclusionary idea of the divine body (200), a point related to several critics’ emphasis on Blake’s view of God both “as Christ” and as a “quantum of divine energy dispersed throughout all life” (Thompson 158) or on his relation to pantheist traditions (Makdisi 249-51). Rowland makes the deeply suggestive point that Paul, in focusing on the community of believers as the body of Christ, never asserts “anything akin to Blake’s ‘every thing that lives is Holy’” (215, quoting The Marriage of Heaven and Hell pl. 27). These points of contact and difference, together with Paul’s ideas on the physical body and bodily restraint, form the backdrop for the Blake texts I consider.

The selected texts work together, each supplying something the others do not. “The Divine Image,” the only one with no significant allusion to Paul (though an implicit differentiation), presents both an idealized statement of and a theological basis for Blake’s view of the body and sexual love as holy.Paul uses “image” or “likeness” mainly to designate Christ’s similitude to God, but occasionally in the poem’s sense, referring to humans’ relation to God (for example, 1 Cor. 11.7, Col. 3.10). The poem’s apparent reference to an ideal and timeless world (and, in biblical reference, a prelapsarian one) is crucial for Blake; it leaves unstated, however, the reality of the present world, seen in its contrary poems, “A Divine Image” and “The Human Abstract.” America plate 8 and “Was Jesus Chaste” deal with the extant world, a key point because Paul’s ethics and idea of Christ’s body were based on what Paul and Blake both see as postlapsarian and, presently, eschatological contexts. These two poems view the world through the distinct lenses of an imminently expected eschaton and of Jesus as ever-present opponent of law and restraint. Both perspectives bring Blake face to face with Paul’s ambiguous legacy as the theorist both of the law’s supersession in Christ’s new dispensation and of voluntary observance of the law and restraint, especially in sexual practices. In these texts, Blake selects two linked statements of Paul’s ideas, both from 1 Corinthians, for polemical contestation (America) and for paraphrase, revision, and recontextualization (“Was Jesus Chaste”). In so doing he states, restates, and then modifies his sense of what the body’s holiness means in the world.

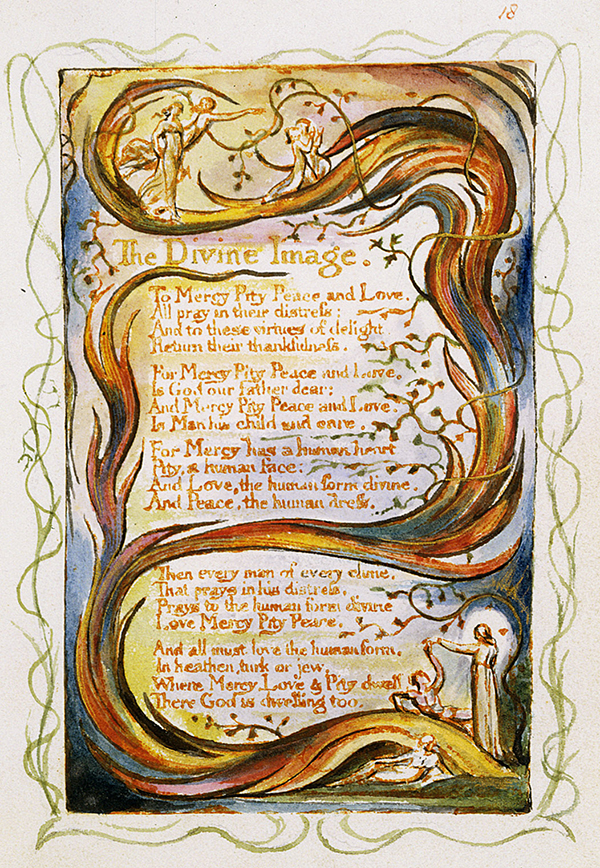

“Love, the human form divine”

“The Divine Image” (1789) reworks and expands a foundational biblical statement, “And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness” (Gen. 1.26), presenting humans’ resemblance to the divine not as the result of an originary act but as a correspondence between qualities of two entities, “God our father dear” and “Man his child and care” (lines 6, 8). Of the four qualities Blake mentions—mercy, pity, peace, and love—the last is said to have “the human form divine” (line 11), though in the fourth stanza all four are said to constitute this form (lines 15-16). Blake’s statement is therefore that love has the “form” of the human body, that this form is itself “divine,” and, by implication, that the particular parts involved in love, including the sex organs, are also divine, not in origin but in themselves (as other physical embodiments of love, such as the mother’s smiles of “A Cradle Song” line 11, would be). By presenting the divine as a manifestation of qualities found in both God and humanity, Blake avoids the implication that bodily and sexual love are sacred only as reflections of God’s love; the qualities and the body are themselves holy, as shown by the fact that we pray “to” them (lines 1, 15). Against this valuation of the body, Leo Damrosch argues that Blake’s formula means “exactly what it says: the form is divine and must be distinguished from ‘the Body of Clay’” (172).Damrosch’s statement (quoting “Was Jesus Chaste” line 94) is part of a chapter section (165-76) arguing that Blake’s idea of the body is dualist as well as Pauline. (His view of Blake’s “every thing that lives” is similar; see 168-69.) Both points have merit insofar as Blake, like Paul, distinguishes between the flesh, or “Mortal part,” and spirit, or that which is “from Generation free” (“To Tirzah” lines 9, 3). Damrosch discounts a major Blake-Paul difference argued below, Blake’s rejection of Paul’s view of the flesh (sarx) as a source of corruption. Indeed, he argues by implication that Blake shares that view, citing varied late works. (Damrosch generally avoids distinctions between early and later Blake.) Blake’s attitudes on this and other topics are often ambivalent, so there is some support for the point; overall, however, Damrosch misses the nuanced quality of Blake’s later presentations of Generation. But most readers, I suspect, will feel that the human form in “The Divine Image” is the physical body, and Gerhard von Rad’s observation about the biblical passage is apt here: “One will do well to split the physical and the spiritual as little as possible” (58). Blake does not say, however, that the divine is present only in the human, as often thought; stanza 2 locates the four qualities in both “God our father” and “Man his child,” with the precise relation between these manifestations undefined. Thus, the view of God’s “immanence and transcendence as contraries or mutually constituting states” in later Blake (Rosso 13) is basic in this early work as well.

This early formulation may seem oversimple, since “The Divine Image” reflects an ideal state. Yet “Love, the human form divine” is a foundational idea in Blake, and its biblical grounding in prelapsarian existence rather than later life, in which the human relation to the divine is compromised, makes this statement a kind of base-level truth for him, comparable to those of other “innocence” poems whose ideas remain central in his work, such as “On Anothers Sorrow.” The line’s very simplicity contributes importantly to later, more complex formulations of the idea that the body is holy, and the phrase “human form divine” itself reappears, always in contexts of fundamental importance, in Blake’s three later long poems as well as in The Everlasting Gospel.See The Four Zoas Night 9, 126.10; Milton 32 [35].13; and Jerusalem 27 [verse].58.

“Every thing that lives is holy”: Blake and Paul in America Plate 8

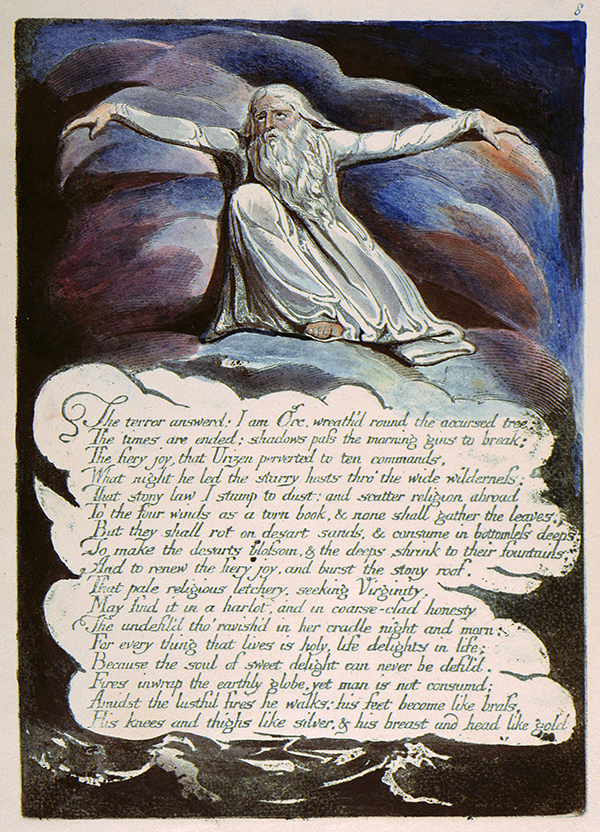

Blake’s “every thing that lives is holy,” in its varied settings, particularly that of America (1793) plate 8, plays a crucial role in the development of his sexual antinomianism. The apothegm itself expands the “human form divine” formula while moving from an unspecified time of innocence to America’s eschatological moment (“The times are ended,” 8.2). Its contexts make clear its primarily moral-sexual reference while connecting it to social-political revolution, women’s status and sexuality, and, in America, oppositional correction of Paul.This and other works composed in the same period refer fairly often to Paul’s writings, which Blake must have known from early on. “To Tirzah” (probably c. 1795—see Viscomi 268, 298-99) quotes 1 Cor. 15.44 as an inscription in its design; Marriage pl. 8 (proverb 25), Howard Jacobson shows, responds to and corrects 1 Cor. 11.7, “The woman is the glory of the man”; Mary Lynn Johnson and John E. Grant find probable allusions in “The Clod and the Pebble” lines 1-3 (1 Cor. 13.4-7), America 5.1 (2 Cor. 3.3), and Europe 13.1-5 (1 Cor. 15.52) (see Johnson and Grant 31n, 88n, 105n). Blake’s watercolor St. Paul Preaching in Athens (c. 1803) presents Paul as an inspired figure. Blake refers to Paul by name in poetry only in lists of churches and sons of Los in The Four Zoas, Milton, and Jerusalem—that is, as a symbol for an epoch in institutional Christianity, and in Los’s related complaint that Paul facilitates Albion’s creation of “Female Will” (Jerusalem 56.42). Finally, the apothegm’s context and development in America link that text and “The Divine Image” to Blake’s deeply antinomian elaboration of Jesus’s identity and of sexual conduct in “Was Jesus Chaste.”

The most plausible biblical source for Blake’s phrase is Psalm 145.17, “The Lord is righteous in all his ways, and holy in all his works,” implying that all God made is holy, but the correspondence is too loose to be decisive. Saree Makdisi, who uses the apothegm’s universalism as part of an important reading of Blake as aligned with anti-empire traditions, relates it to Jacob Bauthumley’s “God is in all Creatures, Man and Beast, Fish and Fowle, and every green thing,” and, more distantly, to hermeticists such as Giordano Bruno (250), but does not comment on its sexual meanings.In contrast to what I argue for Blake, Bauthumley is emphatic that “the flesh [does not] partake of the divine Being” (8). Contrary to some suggestions (Thompson 26), Bauthumley has a fairly standard view of sin as comprising acts and impulses “contrary [to] or below God” (31-42 [40]). In each of its iterations in Blake, however, the formula is associated with physical sexuality. It is counterposed to unmet or wearying “corporeal desires” and to “pale religious letchery,” and associated with “the soul of sweet delight” and with “little glancing wings” that “drink [their] bliss”—not always positively, for in The Four Zoas it and the latter phrases occur in the contexts of sexual reproduction and female entrapment, raising the issue of Blake’s later treatment of Generation, discussed below.See E 590 (annotations to Lavater), in the phrase’s precursor form, “all life is holy”; Marriage pl. 27 (Chorus); America 8.10, 14; Visions of the Daughters of Albion 8.10; The Four Zoas Night 2, 34.78-81, 93-96. Though these contexts differ from one another and from “The Divine Image,” the parallel between “Love, the human form divine” and “every thing that lives is holy” should be clear: as in the earlier poem, here too Blake’s wording must include both the body in general and, implicitly, its sexual organs. Although in early works Blake does not raise the latter idea directly, he could have found support for it in 1 Corinthians 12.23.Jonathan Roberts proposes that 1 Cor. 12.12-27, on the body of Christ, influenced Blake’s aesthetic (68, 71-72); in any case, Blake is likely to have known the passage. Paul argues there that “those members of the body, which we think to be less honourable, upon these we bestow more abundant honour; and our uncomely parts have more abundant comeliness” (12.23). Paul’s reference is to the genitals (Martin 94-95, 269n22); he uses the point as an analogy supporting mutual respect among Jesus’s Corinthian followers, but the statement independently suggests these organs’ beauty and worth.

In addition to this basic meaning, the apothegm is linked to an exposure of the theology of sexual restraint. In Marriage, this exposure occurs through an attack on religious support for chastity, or “that [which] wishes but acts not” (pl. 27, Chorus); in Visions, it is implied through Oothoon’s rhapsodic praise of sexual bliss. In America, the attack on restraint takes the form of a loosely syllogistic argument in which the second term is not necessary from the first: (1) “every thing that lives is holy”; (2) “the soul of sweet delight can never be defil’d”; so (3) the harlot possesses “Virginity” and the “ravish’d” working-class girl (“coarse-clad honesty”) remains “undefil’d” (8.10-14, rearranged). This conclusion may involve the common libertine assumption that such women take pleasure in their sexual exploitation or—more consistent with Visions plates 3 and 6-8—that they maintain a core capacity for sexual bliss despite brutalization.On the critical debates over Visions, especially the once-fraught issue of female degradation in Oothoon’s final speech, see Matthews, introduction and chapter 1, especially the comment that the speech affirms a fundamental “right … of sexual fantasy” (28). Either way, the implication of “Virginity” and “undefil’d”—that these persons are morally untouched, and hence that people and acts usually thought “defil’d” are pure and holy—is the heart of Blake’s polemic.

This argument, transgressive on its face, is also a counterstatement to Paul’s sexual and moral theology, particularly but not exclusively in two passages of 1 Corinthians, 3.16-17 and 6.9-19.As mentioned below, several writers note Blake’s later allusion to 3.16 and 6.19 in “Was Jesus Chaste.” I argue that Blake engages these passages, by allusion, in their full Pauline contexts and as early as America. Both contrast the body’s holiness in Christ with its defilement, the first through one of Paul’s favorite devices, aphoristic antithesis, and the second through extended argument. In the first, application to sexual defilements, among others, is implicit; using the plural for the believing community as a whole, Paul asks, “Know ye not that ye are the temple of God, and that the Spirit of God dwelleth in you? / If any man defile the temple of God, him shall God destroy; for the temple of God is holy, which temple ye are.” In the longer passage, Paul first considers those whose acts bar them from God’s kingdom, including “fornicators,” “adulterers,” the “effeminate,” and “abusers of themselves with mankind,” then distinguishes what is permissible from what is proper: “All things are lawful [permissible] unto me, but all things are not expedient: all things are lawful for me, but I will not be brought under the power of any.” He then mentions two specific violations that should be shunned: joining one’s body “to an harlot,” whereby (as “one flesh”) Christ’s members become “the members of an harlot,” and “fornication” in general. He sums up, echoing 3.16, “Know ye not that your body is the temple of the Holy Ghost which is in you, which ye have of God, and ye are not your own?” (6.9, 12, 15-16, 18, 19).See Fee 243-44, Furnish 87-92, and Sampley 858-59 for issues of translation and varying views of Paul’s strictures on homosexual acts. “All things are lawful for me” is generally taken as a Corinthian maxim that Paul is answering.

Both passages strikingly embody Paul’s ambiguous legacy. The statements that we are God’s temple and our bodies temples of the Holy Ghost, if isolated from Paul’s full argument, bear obvious similarity to Blake’s idea of a divine essence in humanity and the body. Additionally, the central Pauline idea of human participation in Christ’s body, implied here and explicit elsewhere in 1 Corinthians (10.16, 12.12-27), Romans (12.5), and other texts, would have been attractive to Blake. Further, we can assume he would have approved of the eschatological framework of 1 Corinthians and its opposition to social distinctions (part of Paul’s argument against status differences at Corinth; see Martin), though these are not salient in his references.

At the same time, what Blake would see as negative in Paul appears in the warning on defilement in 3.17 and in three features of the longer passage. One is the listing of sexual (and other) practices considered exceptionally heinous in Blake’s era, when Paul’s teaching, though originating in an eschatological context, served as traditional pastoral doctrine. Matthew Henry’s influential biblical commentary, for example, calls these acts “gross sins” and those who commit them “the scum of the earth.”I quote Henry from an unpaginated online source, subdivided by book and chapter. Secondly, 1 Corinthians 6.12 and following provide an elaboration of Paul’s teaching on the supersession of Mosaic law (what he calls being “dead to the law by the body of Christ” in Rom. 7.4) and the resulting issue of whether those “in Christ” are free from any standards or should practice self-restraint. Consistent with his teaching elsewhere,For example, “Shall we continue in sin, that grace may abound? / God forbid. How shall we, that are dead to sin, live any longer therein?” (Rom. 6.1-2). Rowland identifies these verses as rejecting the view that the saved need not have “concern about how one behaves” (203), more or less the idea Paul criticizes in 1 Cor. 6.12. Paul recommends the latter in verse 12: though “all things are lawful,” they may not be advisable and one should master one’s desires; in practice he urges readers to “flee fornication” (verse 18) as well as harlotry in all circumstances.

Finally, Paul’s argument involves underlying assumptions about the relation between spirit and flesh and between the believing community and “the world” (raised in a preceding section on suing in outside, secular courts, 6.1-8, and implicit in the discussion of prostitutes, assumed to be outsiders). These are linked issues for him. Dale B. Martin’s study of the intellectual contexts of 1 Corinthians shows that Paul viewed “flesh” and “spirit” (sarx, pneuma) as radically opposed, with flesh a “corrupt element, that element of the cosmos in opposition to God and the Spirit,” and the source of pollution and impurity in the body’s flesh-spirit continuum (171-73 [172]). While this opposition is only implicit in the 1 Corinthians passages, it is explicit elsewhere (for example, in Rom. 8.13). In parallel, the believing community constituted a holy spiritual body, quite literally the collective body of Christ, governed by spirit and apart from the corrupt outer world (Martin 169-70, 176-79). For Paul, then, both individual and community were in danger of contamination, one by its own flesh and the other by the outside world. Both were holy (a “temple,” 1 Cor. 3.16, 6.19) to the extent that they avoided this contamination.

Blake challenges Paul on all these issues in America plate 8, through pointed uses of Paul’s own language. Placed within this plate’s and the poem’s eschatological framework (8.2), Blake’s phrasing in 8.10-12—“That pale religious letchery, seeking Virginity, / May find it in a harlot, and in coarse-clad honesty / The undefil’d tho’ ravish’d in her cradle night and morn”—replicates and responds to Paul’s repeated use of “harlot” and his warning against those who “defile” God’s temple; his rejection of Paul’s language of defilement echoes and deepens in the concluding line of the passage, “the soul of sweet delight can never be defil’d” (14). Through plate 8’s structure, Blake further takes up Paul’s distinction between being “dead to the law by the body of Christ” (Rom. 7.4) and still being subject to “another law in my members … bringing me into captivity to the law of sin” (Rom. 7.23), an idea closely related to that of being “brought under the power” of desire (1 Cor. 6.12). Plate 8 presents the law’s “death” in its first section, as Orc smashes the Mosaic tablets and “scatter[s] religion abroad” (8.3-7). However, Blake rejects Paul’s qualified approval of the law under the Mosaic dispensation (seen in chapter 7 of Romans and elsewhere), opposing law from the start to “fiery joy” (8.3, 9).Tolley similarly comments about “Was Jesus Chaste” that Blake “goes beyond Paul, in objecting to the Law absolutely” (174). The second part of plate 8, presenting bodily desire as “the soul of sweet delight” and a locus of “Virginity” (in Visions’ sense of “virgin bliss,” 6.6), counters Paul’s view of desire as “the law of sin” and its many analogues elsewhere in Paul.

Finally, and most crucially, “every thing that lives is holy” responds to and revises the deepest level of Paul’s teaching in 1 Corinthians 6, his linked ideas of the community and body. In its universality, the apothegm acts as a counterstatement to Paul’s idea of the body of Christ as a special holiness community, or what Rowland calls Paul’s transfer of “cultic holiness” from the physical temple to “a group of ‘special’ people who behaved in special ways, not like the heathen” (215). In this aspect, Blake’s “every thing that lives” expands Paul’s “the temple of God is holy” (1 Cor. 3.17) from its narrow application to the believing community to apply to all living things. Similarly, but in a more contestative way, the formula’s inclusion of the physical body and (implicitly) genitals revises Paul’s teaching on the flesh (sarx) as a “corrupt element” (Martin 172) insofar as the flesh and its members are part of “every thing that lives.” To be clear, Blake does not necessarily discard any distinction between spirit and flesh, but he does reject the idea that the two are antagonistic. Indeed, his words following “every thing that lives is holy” suggest this rejection: “Life delights in life” and “the soul of sweet delight” imply that physical being and acting possess emotional qualities (“delight”) and allow access to “soul”—broadly speaking, what Paul denies for sarx. Blake’s apothegm, then, allows him to reject Paul’s ethic of restraint and to confront what he sees as the positive and negative in Paul’s “temple of God” without, for the moment, addressing this formula directly.

The centrality of the critique of Paul in Blake’s understanding of the body becomes clearer first from a return to “The Divine Image” and, secondly, from a brief comparison with writing by Abiezer Coppe, the seventeenth-century antinomian often seen as a Blake precursor.Coppe’s relevance to Blake was probably first suggested by A. L. Morton (45-48 and 51-52). See more recent references by Makdisi 97, 291-93, and elsewhere; Rowland 172-74; and Thompson 24, 27. With Paul’s teachings in mind, it is evident that, even before America, the idea of a “human form divine” in “The Divine Image” implicitly rejects Paul’s view of sarx as corrupting, while the further idea that this form is divine in “heathen, turk or jew” (line 18) similarly contravenes Paul’s restrictive sense of Christ’s body. By comparison, Coppe, who expresses transgressive sexual ideas with some similarity to Blake’s, including justification of “wanton kisses” (46), does not reject Paul’s sense of the corruptness of flesh. Coppe bases these ideas on his own reading of Paul’s teaching against status and hierarchy, specifically on Paul’s words that “God hath chosen Base things, and things that are despised, to confound—the things [that] are” (Coppe 43; 1 Cor. 1.28). But if this appropriation shows a theologically adept use of Paul, it also shows entrapment in his dualism and belief in sexual sin. Coppe’s celebration of “wanton kisses” reads as an affirmation of transgression within Paul’s terms, one that still feels sin as truly sinful, though to be gloried in as part of exalting the despised. In contrast, Blake’s view of the flesh and bodily love as sacred in themselves rests both on his initial adaptation of this idea from Genesis 1 and on his later use of “every thing that lives” to answer Paul’s dualism and exclusivity.

“Was Jesus Chaste”: Reassessing the Temple

“Was Jesus Chaste,” section f of The Everlasting Gospel (c. 1818), based on the story of the woman taken in adultery (John 8.3-11),Blake uses the name Mary for the unnamed woman, based on the patristic conflation of her with Mary Magdalene, from whom Jesus purged seven devils (Mark 16.9, Luke 8.2). provides a much later and more radically antinomian treatment of Blake’s ideas on sex and the body, in light of his later concern with imperfection and sin. The story is an ideal vehicle for Blake. It allows him to complete and then go beyond his critique of Paul; additionally, while it is sometimes marginalized in modern theological commentary because added to John’s Gospel after the earliest known texts,See O’Day 627-30 for the textual history and a treatment minimizing the story’s moral importance; Ashton omits it altogether. the episode’s teaching of tolerance or forgiveness has made it one of the most prominent parts of John in the popular imagination. “In no other place,” a character in fiction thinks, “did the Saviour speak with greater sweetness.”Rölvaag 199. This twentieth-century novel about Norwegian Lutheran immigrants in the US mentions the passage twice (once in full quotation) to connote forbearance toward disfavored sexual and social practices. This quality, we will see, is not only opposed to Paul’s censures against sexual transgression, but also lets Blake broach the very broad question of how or whether an ethic of sexual holiness should become operative in Generation.

Though the poem (section f, my focus here) is based on John and paraphrases several of Jesus’s statements from John (omitting the last, “Go, and sin no more,” 8.11b),Blake paraphrases John 8.7 and 10-11 in lines 26 and 47-49; the most likely reason for omitting 8.11b is that this injunction is unreasonable in the world of Generation (see below). Paul is still a major target. Blake’s dramatization achieves its restatements through direct opposition to Mosaic law in its first half, and, in its second, through continuing Blake’s engagement with Pauline morality. Here, Blake appropriates and revises Paul’s temple metaphor in a way that opens unexpected new complexities, which bring the idea of a “human form divine” fully in touch with his late concerns. In the process, “Was Jesus Chaste” redefines sin and blasphemy—but in deeply problematical ways—as well as forgiveness, and it also radically shifts the poetic gendering of theological authority.

In the poem’s reconsideration of sexuality and redemption, its overtly antinomian first part—including the statement by Jesus (Jesus’s or God’s “breath,” lines 10, 19) that “Good & Evil are no more” (line 21) and Jesus’s attack on the “Angel of the Presence Divine,” a “demiurge and lawgiver” (Rowland 187) who is an aspect of himself—is less central than its subsequent theological revisions in dialogue between Jesus and Mary (lines 43-80).On the Angel, a recurrent figure in Blake’s works, see Rowland, especially 73-75 (on biblical backgrounds) and 185-87 (on this poem). On this figure as an aspect of Jesus, see line 33, “My Presence I will take from thee”; on its affinity with the “shadowy Man” (lines 81-96), see below. The two major recent interpreters of this latter material see it differently. Morton D. Paley believes Mary’s view of herself as “a sinner in need of forgiveness” violates the poem’s premise of the “holiness of physical love” (194); Rowland sees no such violation, since the sins of hypocrisy and conventionality that Mary confesses, as well as Jesus’s distinction between “love” and “Dark Deceit” (line 58), assume that “love is not a crime” (188). Paley’s point remains apposite, however, in light of late-eighteenth century debates that “focus[ed] specifically on questions of female sexuality” (Matthews 188), since Mary shows considerable shame over her acts. My analysis, incorporating this point, builds on but also diverges from Rowland’s.

The Holiness of the Body and Genitals (Jesus and Mary)

In casting out Mary’s seven “Devils” or accusers, Jesus tells them they “Shall be beggars at Loves Gate”; Mary, explaining her actions, says the accusers treat as “a shame & Sin / Loves Temple that God dwelleth in,” making it a “hidden Shrine” in which to hide “The Naked Human form divine” and scorning as “Lawless” that “On which the Soul Expands its wing” (lines 56, 63-68). The shrine image refers to the “religion of chastity and holiness” that Blake explores in Jerusalem and other later works (Rosso 158 and elsewhere), which treats women’s sexuality as such a shrine or tabernacle, enticing and forbidden at once.Schuchard, in associating Moravian uses of “chapel” and “tabernacle” for the vagina with Blake’s (“‘The Secret’” 212), seems not to note the negative connotations Blake gives shrine, chapel, and tabernacle. See Schuchard’s Why Mrs. Blake Cried for her overall analysis. Jesus’s and Mary’s phrases, in contrast, repeat the basic idea of sexual holiness—“Loves Gate” probably denotes the vagina (a place by which love is allowed entry), while “Loves Temple” may do so as well, or refer to a woman’s body as a whole. In these lines Blake makes explicit the holiness of the genitals, implied but not stated in “The Divine Image” and America plate 8 and its cognates, and he underlines the foundational importance of “The Divine Image” by repeating its signature phrase as the target of the accusers’ cult of chastity.

Redefining the Temple (Mary)

Besides its direct metaphorical reference, Mary’s phrase “Loves Temple” also alludes to 1 Corinthians 3.16 and 6.19, as several commentaries note.See Tolley 175, Paley 194 (6.19 only), and Rowland 259n14. However, Blake’s words do not simply appropriate but radically revise Paul, whose point is that the temple or body, individual and collective (the believing community), essentially belongs to God. Discussing 3.16, J. Paul Sampley notes both the theological point that calling the body a temple identifies it as “God’s special building”—“ye are not your own” but God’s, Paul admonishes believers (6.19)—and the cultural resonance that “Gentiles and Jews at that time were familiar with the care given to protecting the holiness of temple sites as a fundamental reverence for the deity in charge” (831-32). Moreover, as buildings dedicated to God, the individual and collective bodies are to live according to the spirit, subordinating the flesh: “Ye through the Spirit [shall] mortify the deeds of the body” (Rom. 8.13). “Loves Temple,” by contrast, particularly in its structural parallelism with “Loves Gate,” its pairing with “The Naked Human form divine,” and its reference to an act of physical sex, means that the body and genitals are of and for love, so that the temple becomes human and physical, a temple to a human divine capacity, and eliminates the flesh-spirit dichotomy implicit in Paul. In sum, to say God dwells in “Loves Temple” is quite different from saying the body should be God’s temple.

“Loves Temple” completes Blake’s reassessment of 1 Corinthians 3.16-17 and 6.9-19 on one level, insofar as Mary’s redefinition finishes Blake’s correction of Paul’s devaluation of the body and his strictures on specific acts. Blake has not fully completed his critical engagement with Paul, however, since the redefinition does not deal with two broader aspects of Paul’s moral theology, his view of the body of Christ as an exclusionary community and his judgments on those outside it. Blake, we will see, in a deeply meaningful narrative choice, locates these aspects of Paul’s theology in Jesus himself, manifested in his words to Mary, “What was thy love Let me see it / Was it love or Dark Deceit” (lines 57-58).

Redefining Sin, Blasphemy, and Forgiveness (Mary)

As part of a long response to Jesus’s question (lines 59-80), Mary offers several possible explanations of her conduct, adds the temple statement, and offers what amounts to a redefinition of sin and blasphemy:

But this O Lord this was my Sin

When first I let these Devils in

In dark pretence to Chastity

Blaspheming Love blaspheming thee (lines 69-72)

Sin and blasphemy, then, are not attributes of conventional illicit sex but precisely the attitudes that reject this sex as sinful. As Rowland points out, “The sin to which Mary confesses … is hypocrisy, habit, a pretence to chastity,” rather than her sexual acts, while “blaspheming love had meant blaspheming Christ” (“thee,” line 72) and amounts to “a denial of the Holy Spirit” (188). While these redefinitions are valid on one level—Mary has not acted from love—I differ from Rowland in not seeing them as simple and unproblematical. Indeed, it is on this point that Blake, having made his most radical revision of Paul in the redefinitions of the temple and of sin and blasphemy, radically rethinks the implications of that revision.

The problem stems from Jesus’s question about Mary’s experience. From Mary’s first words, “Love too long from Me has fled. / Twas dark deceit to Earn my bread / Twas Covet or twas Custom or / Some trifle not worth caring for” (lines 59-62), we realize how much she internalizes Jesus’s distinction. We realize, too, that the redefinition of the temple also responds to that distinction, in a deeply ambiguous way. If positive in rejecting Paul’s subordination of the body and his specific moral stances, the temple redefinition also opens the way to a new dualism between treating the sexual body as sacred and as less than sacred, and a new exclusionism toward those who do the latter. (In effect, they have defiled the temple, not through specific acts but through using it without reverence.) Further, while recognizing that her “Sin” was to “let these Devils in” (to devalue the temple as “shame & Sin” and make “pretence to Chastity”), Mary also views her acts as a source of genuine shame: “Thence Rose Secret Adulteries / And thence did Covet also rise” (lines 73-74). In sum, Mary’s responses, including her list of motives and acts (lines 59-62, 73-74) and her redefinitions of the temple (lines 64-68), sin, and blasphemy (lines 69-72), all show the risk of enacting a new and rigid religion of holiness, this time of the sexual body, and a new ethic of shame for debasing it.

“Blaspheming,” in this context, is a particularly percussive term, for given the near-sacred valuation of love in Mary’s statement, as well as the inclusion of “thee” or Jesus (based on “the breath Divine is Love,” line 42), the formula recalls Jesus’s words defining what is often called the sin against the Holy Ghost: “But he that shall blaspheme against the Holy Ghost [Spirit] hath never forgiveness” (Mark 3.29, also noted by Rowland 188). Mary is afraid, then, that her acts may merit damnation without possible reprieve. All these ideas stem from and build on the dualism in Jesus’s original question (line 58).

While Mary shows no apparent awareness of this point, her own words, “to Earn my bread,” expose the hollowness—indeed, male incomprehension—of Jesus’s distinction. Easy to valorize because of the speaker, Jesus’s words overlook the realities that prostitutes must sell sex to earn bread and, further, that people do engage in sex out of “Covet” (advancement of various kinds), “Custom” (whether the “frozen marriage bed” of Visions 7.22 or the mixed emotions of a marriage voluntarily maintained over a lifetime), and the thousand “trifle[s]” of ordinary life, including sheer sexual attraction without love. All these, of course, impinge most on women, though to some degree on everyone. Further, and more basically, to describe Jesus’s words as shallow and uncomprehending is also to say they are theologically inadequate, in two ways. They are pharisaical, in the sense of designating a group of people (those capable of living for and by love) assumed to be superior to others, and they are soteriologically empty, in that they cannot save the people Jesus has come to save.

There is no way out for Mary within this self-accepted duality, which can only condemn her acts. The result is an intuitive leap of astonishing power, in four passionate questions that supersede Jesus’s dualism without seeming to:

My Sin thou hast forgiven me

Canst thou forgive my Blasphemy

Canst thou return to this dark Hell

And in my burning bosom dwell

And canst thou Die that I may live

And canst thou Pity & forgive (lines 75-80)

The questions supersede Jesus’s distinction because they apply to the ordinary terrain of human life that his distinction neglected. This terrain is also that of Blake’s state of Generation, the condition of ordinary sexually generated or “vegetated” bodies, with which much of his late work, and implicitly this poem, is concerned. Generation, Blake’s readers know, is the arena of much behavior that is degraded and cruel, that denies and blasphemes the spirit, but it is also the site of countervailing actions: “Then Los conducts the Spirits to be Vegetated, into / Great Golgonooza … / … / That Satans Watch-Fiends touch them not before they Vegetate” (Milton 29 [31].47-50). Generation, G. A. Rosso argues, cannot be avoided but must be the ground of the struggle to transcend its own limits; the “core falsehood” identified in Blake’s myth, that “humanity is reducible to a generated body,” is “false because the body also partakes of the immaterial divine realm, making that realm accessible” (187).Rosso’s chapter 5 (on Jerusalem) is the best account of the dual aspects of sexuality in Generation. I return to Blake’s assessment of this topic in my conclusion. Within this arena of struggle, forgiveness is necessary because of the betrayals we all commit daily in Generation—admitting the “religion of chastity” into our minds, devaluing the body and genitals, and more. These are why, despite Mark 3.29, the Jesus Blake imagines cannot condemn the behavior he has differentiated from love but must forgive it: if, indeed, having sex for the wrong reasons “hath never forgiveness,” who can hope to be forgiven?Moskal’s brief discussion of “Was Jesus Chaste” (41-42) misses this concern with Generation. Her chapter summation characterizes Blake’s idea of forgiveness as based on contrariety—that is, recognizing and accepting, rather than negating, others’ “acts of imagination according to their own genius”; forgiveness is “achieved in the face of good, namely the continual exposure to the individual genius of others” (47). These formulations are devastatingly inadequate to Blake’s emphases on intended injury and self-betrayal in Generation. As his question to Mary shows (“Was it love or Dark Deceit”), the poem’s Jesus is already prepared to accept “acts of imagination”; Mary’s failures to live according to imagination (“Love too long from Me has fled”), which all in Generation share to some extent, are what open up the necessity of universal forgiveness. Forgiveness in this sense, moreover—if granted—is not individual but part of Blake’s (and, changing what must be changed, Paul’s) body of Christ, a community that affords a “space” in which those bodies not able through error, convention, circumstance, or cowardice to live in the temple may become able to do so.Similar examples include the “Spaces of Erin” (Jerusalem 9.34, 11.12) and the “Space” that grows from Gwendolen’s Falsehood in which Los plants seeds of redemption (Jerusalem 84.31-85.5); see Essick 206-07, McClenahan 150, 152, and Rosso 189. This necessity also means that the Jesus seen in lines 1-80 has not yet become the Jesus Blake wishes us to see.

Regendering Theological Authority (Narrator)

In the coda of “Was Jesus Chaste,” Blake makes an unexpected narrative move that leads to its conclusion. The narrator does not specify any response by Jesus to Mary’s questions, but follows them with new information: “Then Rolld the shadowy Man away / From the Limbs of Jesus to make them his prey” (lines 81-82). Thus, the poem seems to shift focus. The “shadowy Man,” newly introduced, is an aspect of Jesus himself (part of his “Limbs,” line 81) and similar in some ways to the Angel of the Presence Divine, likewise an aspect of Jesus (“My Presence I will take from thee,” line 33). The Angel, by implication, was that part of Jesus’s theology that initially accepted the law, and so was rejected in the antinomian affirmation of the poem’s first segment. In contrast, the “shadowy Man” seems more bound up with Jesus’s inner being, but, similarly to the Angel, rejects part of Jesus, his fellowship with those “God has afflicted for Secret Ends / He comforts & Heals & calls them Friends” (lines 89-90; see “On Anothers Sorrow”). However, while the introduction of the shadowy Man is crucial to the poem’s outcome, the shift in emphasis is only apparent. The narrative fact that Mary’s questions are immediately followed by the shadowy Man’s action implies that Jesus’s responses, whether spoken or in his heart, must have been positive, since the shadowy Man, opposing Jesus’s oneness with sufferers, now divides from him. Additionally, and crucially, we can infer that Jesus’s prior implied judgment on Mary (“Was it love or Dark Deceit”) resulted partly from the shadowy Man’s presence within him. Finally, it seems probable that with these lines Blake is not simply jumping to the moment of the crucifixion (anticipated in lines 82, 85, and 91-93) but evoking a fictive new phase in Jesus’s ministry, more fully antinomian (11-42) and more antithetical to the world’s judgments (43-82), that leads toward that outcome.Erdman considers the shadowy Man “all that remains of the ‘Angel of the Presence’” (345), a view similar to mine; Paley as Jesus’s “Spectre” (194); Pearce as “the historical Christ” (of the church) as opposed to the “spiritual Jesus” (61); Rowland as similar to the “selfhood” (188). There is no suggestion of a turning point in John, whose chronology places the incident about half a year before Jesus’s crucifixion the following Passover. Thus, the poem’s crucial event, Jesus’s achieving his identity as savior of all, is determined by his silent acceptance of Mary’s standard of forgiveness in the space between lines 80 and 81.

Several interpretive conclusions emerge from this denouement and the poem’s earlier segments. First, Blake fictionally posits a three-step crystallization of Jesus’s view of sin and forgiveness through this one incident: Jesus solidifies the rejection of law (lines 11-42); completes his rejection of Paul’s theology of restraint within the former law, instead implying a standard of the holiness of sexual acts undertaken in love (lines 57-58); and confronts the exclusionary and pharisaical aspects of that standard through his forgiveness of those who violate it (implied in lines 81-82). These steps dramatize Blake’s own evolved view of sacred sexuality (and perhaps his progression toward it), involving an acceptance that his early statements of the body’s divinity (“The Divine Image”) and the holiness of life and transgression (America pl. 8 et al.), while remaining fully valid, are not adequate to what he now sees as the complex landscape of Generation.

“Was Jesus Chaste” also, in some sense, goes further than Jerusalem in its idea of forgiveness. Jerusalem, at least on the surface, restricts itself to conventionally defined sins. Crucially, the tableau involving Jesus’s mother, Mary, and Joseph (pl. 61), central in Jerusalem’s treatment of this topic, focuses on adultery as a forgivable sin, without asking if adultery can ever be justified. Elsewhere, I have argued that this self-limitation in Jerusalem is part of a narrative strategy of offering broad common ground to those who accept conventional ideas, in effect creating a “fusion of tolerance with continued debate over its full meaning” (Hobson 182). “Was Jesus Chaste,” in contrast, defines in Blake’s own terms the full meaning of his sexual antinomianism. This poem, concerned with the same conventional sin as Jerusalem plate 61, asserts its potential holiness through Jesus’s dismissal of the accusers and his words in lines 57-58, but then moves to the implied new standard of holiness that this affirmation raises, and shows that violation of that standard, as of conventional ones, cannot be a bar to entry into Jesus’s body.

Finally, each of these issues—the narrative outcome, the redefinitions of sin, blasphemy, and forgiveness, and the latter’s broad catholicity—involves a regendering of the poetics of theological authority. This point is relevant to arguments in recent general and gender-focused Blake criticism that find strong elements of female autonomy in Blake’s works. Rowland argues, for example, that in Blake’s watercolor The Woman Taken in Adultery (c. 1805), on the same subject as the present poem, “it is Jesus who in stooping to the ground in effect bows before the woman”; visually, “Jesus the Divine Human honours another with the divine image in her” (181-82; see John 8.6, 8). Similarly, Susan Matthews urges that in The Penance of Jane Shore (exhibited 1809), Shore’s “erect and dignified figure” makes “a coded reference to [Blake’s] continuing defence of active female sexuality” and against “scapegoating of the adulterous” (197, 198). Both interpreters, then, see female characters projecting divinity or dignity through physical affect. Beyond such implied messages, others believe female mythic characters in Blake’s later works play symbolically and theologically independent, initiating roles, as Catherine McClenahan argues for Erin (157-58) and Rosso for Ololon (145-56). Mary in “Was Jesus Chaste” fits both points, especially the latter.

While in one sense, as discussed earlier, Mary is intellectually entrapped within Jesus’s initial dualism, her assertive voice in the text is the equivalent of the self-reliant visual affect that Matthews notes in Jane Shore. Further, she shows an active, probing intellect that, while not challenging Jesus’s distinction or his theological authority in making it, works out its implications, applies them to her own case, then appeals against their consequences, and in this way becomes part-author of the outcome. From the point at which Jesus’s voice ceases (line 58), it is Mary who is responsible for each of the redefinitions in lines 59-80; who explains her motivations and so, by implication, reveals the inadequacy of Jesus’s dualism; and who thereby brings him to abandon it and complete the theological evolution just described.Though one might argue that Jesus’s “love or Dark Deceit” is parabolic, designed to prompt Mary’s further thought, the text provides no evidence for this view, and the Jesus of this work generally says just what he means (for example, lines 49-56). In this respect, the poem contrasts with Jerusalem plate 61, in which the crucial interpretation of sin and forgiveness is provided by males (the Divine Vision/Voice or Lamb, God’s Angel, and then Joseph) to females (Mary and, in vision, Jerusalem) (see 60.5-61.17). Noting Mary’s active role does not mean, of course, that Jesus plays no role of his own. It does mean that both the intellectual process leading to the poem’s outcome and that outcome itself occur through a plural theological agency that is both male and female, fracturing conventional ideas of theological authority as univocal and male. In keeping, then, with the revisioning of women’s roles others have seen in later Blake works, and particularly by incorporating intellectual definition and interrogation, this poem’s female character has significantly affected its meaning. Mary’s assertiveness and questioning contribute decisively, though not unilaterally, to closing its plot, making Jesus into what we think of as “Blake’s” Jesus, and, most fundamentally, situating the holiness of the body in the context of our attempt in Generation to become more fully human.

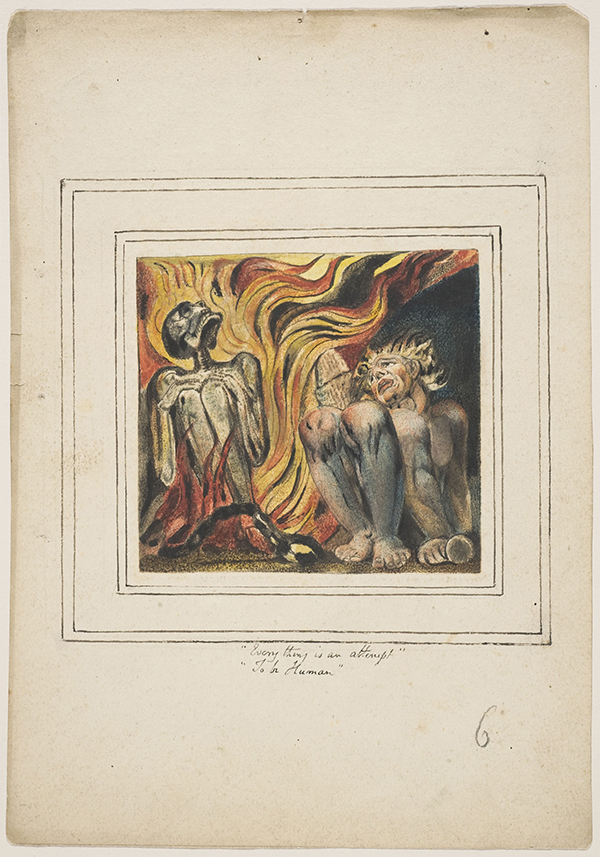

Conclusion: “‘an attempt’ / ‘To be Human’”

Two principal points follow from my discussion. Methodologically, Blake’s habitual procedure of revisionary appropriation of the Bible, rather than influences from earlier or contemporaneous radical Christianities, provides the best key to the inner logic of his evolving sexual ideas. As seen earlier, this logic takes him from early assertions of bodily and sexual holiness through condemnation of law and restraint to a new ethic of holy sexuality that is, finally, relativized as one but not the only way of living in Generation as part of Jesus’s body. At every point in this evolution Blake adapts, extends, contests, and revises biblical ideas, particularly from Genesis and the Pauline epistles. While current and earlier theological traditions may have provided some context, direct use and revision of biblical ideas drive Blake’s evolving treatment of sex.

Substantively, the richest stage of the evolution traced here is the last. This point can be understood more clearly through a double juxtaposition, with Damrosch’s critique of Blake in Symbol and Truth in Blake’s Myth, mentioned above, and with a lesser-known contemporaneous work by Blake himself. In three major chapter sections on sexuality (194-243), Damrosch argues that Blake’s presentations exemplify the “Problem of Dualism” (chapter title) in ways that deepen over time. Blake’s early works, he believes, envision a “sexual paradise” that Blake also portrays as undercut by “the gap between sex as experienced and sex as a wished-for ideal” (195, 199). Later works, Damrosch contends, reify the dualism, excluding sex from Eden and “demoting” or “dismissing” it to Beulah (234, 236, 238) while, on the other hand, regarding sex in Generation as essentially negative and entrapping: Blake “appears increasingly troubled by the fact that the ‘places of joy & love’ … are ‘excrementitious’” (196, quoting Jerusalem 88.39). Damrosch notes that Los’s Spectre is speaking, but adds that “it would be hard to deny that [Blake] has experienced the uneasiness that the Spectre expresses” (196).

It is easy to quarrel with Damrosch’s specifics, including his view of Eden as sexless (on this point see Connolly 214-21, Hobson 169-70) and his discounting or omission of late passages on the holiness of sex and the genitals, such as “Was Jesus Chaste” lines 64-66 (briefly mentioned on 196) or Jerusalem’s invocation of “holy Generation,” in which the Lamb of God appears in Generation’s “gardens” and “palaces” (7.65, 69). More fundamentally, Damrosch was at least approximately right in seeing an unacknowledged dualism in Blake’s earlier work, but wrong in finding that Blake’s evolution reified this dualism in an Eden-Generation split in later work, rather than acknowledging it as a duality within Generation itself. His theorization owes much to reliance on an idea of Generation taken over from critical tradition—“the fallen world of generation, which [sex] perpetuates by its power of reproduction” (198)—in place of full analysis of Blake’s presentations of sex in Generation. Those presentations, in both “Was Jesus Chaste” and Jerusalem, lead to a mixed, partly contradictory recognition of the holiness of sexual life and the inability of many to live in this holiness, and hence of what I call above “our attempt in Generation to become more fully human.”

Those words are not mine alone, but draw on one of Blake’s most suggestive, if gnomic, works, a version of the image of two males, one chained and the other with a hammer, also found in The Book of Urizen and A Small Book of Designs copy A. Probably printed at the same time as copy A, but finished for the Small Book of Designs copy B about 1818, contemporaneously with “Was Jesus Chaste” and late work on Jerusalem, this page is one of several for copy B that came to light only in 2007.See Butlin and Hamlyn for particulars, especially p. 65 for the image and p. 58 for the image description. The Urizen image is plate 11 in Erdman’s numbering (object number varies in the Blake Archive); the Small Book copy A image is object 19 in the archive. In the image’s original context in Urizen, the figures represent Urizen and Los, who, after hammering a form for Urizen, sinks back in the image, having “shrunk from his task” (13.20). A leaning or falling tower and a domelike shape in the background suggest the “revolutions of empires” theme that preoccupied Blake at the time. As the image is re-presented in Small Book copies A and B, with no narrative specifying these identities, the figures seem more general emblems, perhaps slave or prisoner and free laborer (the chains and hammer), or a human creation and creator in general. The radical new element in Small Book copy B is Blake’s caption, “‘Every thing is an attempt’ / ‘To be Human’”. This gives the design a new interpretive context in which the figures remain situated in history, suggested by the tower and dome, but their individual efforts and their relationships to each other and to history emerge as “attempt[s] / To be Human.”

Of course, we must ask what it means to “attempt / To be Human.” In Blake’s terms, the figures with their background seem to mean that “Human” is what we all are, in all our blood and filth. Thus, the long history of war, enslavement, and degradation, as well as hope and love, that Blake begins chronicling in Urizen, including our lives in Generation, shown in both “Was Jesus Chaste” and Jerusalem, are “attempt[s] / To be Human.” At the same time, for Blake the “Human” is the potential for Eden within us individually and as parts of the human populations that his emblematic figures suggest. The “Human,” further, is the “human form divine,” not only the beautiful bodies of sexual beings and their often dishonored loves, but also their attempts to live and move forward in Generation. Blake does not know how—even whether—this move forward will occur, but he knows the attempt exists. In this sense, the design and inscription from Small Book copy B and “Was Jesus Chaste” comment on each other, and both together comment on Blake’s masterwork Jerusalem: “Every thing” that these works describe is an attempt “To be Human.” Finally, in the present context, “‘Every thing is an attempt’ / ‘To be Human’” can be heard as an echo—in effect a distinct, late iteration—of the signature phrase in America and sister works, “every thing that lives is holy,” claiming both less and more than they: not an extant holiness but an attempt to move forward to a full, if imperfect, humanity.

Works Cited

Ashton, John. Understanding the Fourth Gospel. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Bauthumley, Jacob. The Light and Dark Sides of God. 1650. N.p.: ProQuest-EBBO Editions, n.d. [print on demand, 2017].

Blake, William. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. Ed. David V. Erdman. Newly rev. ed. New York: Anchor-Random House, 1988.

Butlin, Martin, and Robin Hamlyn. “Tate Britain Reveals Nine New Blakes and Thirteen New Lines of Verse.” Blake 42.2 (fall 2008): 52-72.

Connolly, Tristanne J. William Blake and the Body. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.

Coppe, Abiezer. “A Second Fiery Flying Roule.” 1649 [i.e., Jan. 1650]. Selected Writings. Ed. Andrew Hopton. London: Aporia Press, 1987. 35-55.

Coppedge, Allan. Shaping the Wesleyan Message: John Wesley in Theological Debate. 1987. Nappanee, IN: Francis Asbury Press, 2003.

Dallimore, Arnold. George Whitefield: The Life and Times of the Great Evangelist of the Eighteenth-Century Revival. Vol. 2. 1980. Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 2015.

Damrosch, Leopold, Jr. Symbol and Truth in Blake’s Myth. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980.

Davies, Keri, and David Worrall. “Inconvenient Truths: Re-historicizing the Politics of Dissent and Antinomianism.” Re-envisioning Blake. Ed. Mark Crosby, Troy Patenaude, and Angus Whitehead. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. 30-47.

Erdman, David V. “‘Terrible Blake in His Pride’: An Essay on The Everlasting Gospel.” From Sensibility to Romanticism: Essays Presented to Frederick A. Pottle. Ed. Frederick W. Hilles and Harold Bloom. New York: Oxford University Press, 1965. 331-56.

Essick, Robert N. “Erin, Ireland, and the Emanation in Blake’s Jerusalem.” Blake, Nation and Empire. Ed. Steve Clark and David Worrall. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. 201-13.Fee, Gordon D. The First Epistle to the Corinthians. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1987.

Furnish, Victor Paul. The Moral Teaching of Paul: Selected Issues. 3rd ed. Nashville: Abingdon, 2009.

Henry, Matthew. Matthew Henry’s Commentary on the Whole Bible. 1706–20. Blue Letter Bible. Study Resources: Text Commentaries: Matthew Henry: Commentary on 1 Corinthians 6. <https://www.blueletterbible.org/Comm/mhc/1Cr/1Cr_006.cfm>. Accessed 2 April 2017.

Hobson, Christopher Z. Blake and Homosexuality. New York: Palgrave, 2000.

Jacobson, Howard. “Blake’s Proverbs of Hell: St. Paul and the Nakedness of Woman.” Blake 39.1 (summer 2005): 48-49.

Johnson, Mary Lynn, and John E. Grant, eds. Blake’s Poetry and Designs. 2nd ed. New York: Norton, 2008.

Makdisi, Saree. William Blake and the Impossible History of the 1790s. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

Martin, Dale B. The Corinthian Body. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

Matthews, Susan. Blake, Sexuality and Bourgeois Politeness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

McClenahan, Catherine L. “Blake’s Erin, the United Irish, and ‘Sexual Machines.’” Prophetic Character: Essays on William Blake in Honor of John E. Grant. Ed. Alexander S. Gourlay. West Cornwall, CT: Locust Hill Press, 2002. 149-70.

Mee, Jon. Dangerous Enthusiasm: William Blake and the Culture of Radicalism in the 1790s. 1992. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994.

Morton, A. L. The Everlasting Gospel: A Study in the Sources of William Blake. London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1958.

Moskal, Jeanne. Blake, Ethics, and Forgiveness. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994.

O’Day, Gail R. “John.” The New Interpreter’s Bible. Vol. 9. Ed. Leander E. Keck et al. Nashville: Abingdon, 1995. 491-865.

Paley, Morton D. The Traveller in the Evening: The Last Works of William Blake. 2003. Rev. ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Pearce, Margaret. “‘The Everlasting Gospel’: A New Exegesis.” Aligarh Journal of English Studies 16.1-2 (1994): 47-63.

Rix, Robert. William Blake and the Cultures of Radical Christianity. Farnham: Ashgate, 2007.

Roberts, Jonathan. “St. Paul’s Gifts to Blake’s Aesthetic.” Visions and Revisions: The Word and the Text. Ed. Roger Kojecký and Andrew Tate. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2013. 67-78.

Rölvaag, O. E. Peder Victorious: A Tale of the Pioneers Twenty Years Later. Trans. Nora O. Solum and Rölvaag. 1929. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1982.

Rose, Edward J. “Blake’s Jerusalem, St. Paul, and Biblical Prophecy.” English Studies in Canada 11.4 (Dec. 1985): 396-412.

Rosso, G. A. The Religion of Empire: Political Theology in Blake’s Prophetic Symbolism. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2016.

Rowland, Christopher. Blake and the Bible. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

Sampley, J. Paul. “The First Letter to the Corinthians.” The New Interpreter’s Bible. Vol. 10. Ed. Leander E. Keck et al. Nashville: Abingdon, 2002. 771-1003.

Schuchard, Marsha Keith. “The ‘Secret’ and the ‘Gift’: Recovering the Suppressed Religious Heritage of William Blake and Hilda Doolittle.” Women Reading William Blake. Ed. Helen P. Bruder. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. 209-18.

———. Why Mrs. Blake Cried: William Blake and the Sexual Basis of Spiritual Vision. London: Century, 2006.

Thompson, E. P. Witness against the Beast: William Blake and the Moral Law. New York: New Press, 1993.

Tolley, Michael A. [J.]. “William Blake’s Use of the Bible in a Section of ‘The Everlasting Gospel.’” Notes and Queries 9.5 (May 1962): 171-76.

Viscomi, Joseph. Blake and the Idea of the Book. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Von Rad, Gerhard. Genesis: A Commentary. Trans. John H. Marks. Rev. ed. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1972.