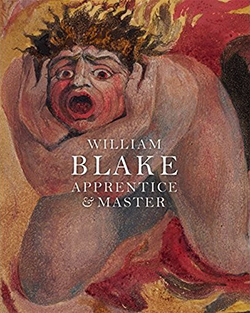

We have come to expect a recognizably edited version of Blake—a Blake of bright colors and identifiable political beliefs. The designers at the Ashmolean did a good job of providing this, choosing as poster for the exhibition the stunning image of “Los howld” from copy A, Small Book of Designs. On paper this image is tiny: 119 x 105 mm. Scaled up to form a poster, this small image both grabs the attention of the visitor arriving at Oxford railway station and dominates the screen <http://www.ashmolean.org/exhibitions/williamblake/events>:

In this design, the red of eyes and mouth and flames become the red of the word “Blake.” Are the “Final Weeks” a warning of apocalypse? But it also offers a puzzle, for this naked figure in torment looks like neither apprentice nor master. The exhibition (and Michael Phillips’s scholarly catalogue) tell a story quite different from that which a visitor drawn in by the exhibition image might have expected.

If Blake’s varied incarnations in major UK exhibitions since 2000 are anything to go by, millennial Blake is taking on new meanings. The major Tate exhibition of 2000 (the work of Robin Hamlyn and Phillips) offered a Gothic Blake: a first section titled “One of the Gothic Artists” led to “The Furnace in Lambeth’s Vale” and “Chambers of the Imagination.” The final section displayed all 100 plates of copy E of Jerusalem: a forbidding wall of words spread unreadably out across a wall, the work of some outsider artist. Gothic again provided the explanatory framework for Tate’s 2006 Gothic Nightmares: Fuseli, Blake and the Romantic Imagination, curated by Martin Myrone. In a paper for a conference to complement the Ashmolean exhibition, Myrone presented Gothic as a slippery term that nevertheless locates Blake’s work within the profane materials of his culture’s imaginary. As a Gothic artist, Blake uncovers tensions and contradictions in the culture of his time. This Blake is an artist who can fail technically, but whose failure is interesting.

In 2009, Tate Britain’s restaging of Blake’s 1809 one-man exhibition presented an artist struggling with paint that had a will of its own, experimenting recklessly with materials that would themselves darken and thicken with age. According to Myrone’s edition of A Descriptive Catalogue, Blake’s decision to include a number of paintings that he viewed as failures “serves to dramatise the creative process in terms of spiritual struggle and exorcism.”Martin Myrone, ed., Seen in My Visions: A Descriptive Catalogue of Pictures (London: Tate Publishing, 2009) 30. This small exhibit was described in a one-star review by Richard Dorment as “a failure—but such a strange, touching, interesting failure that I can’t help but admire the gallery for mounting it.”<http://www.telegraph.co.uk/journalists/richard-dorment/5189154/William-Blake-exhibition-Tate-Britain-review.html>. A small but significant improvement on Hunt’s “farrago of nonsense, unintelligibleness, and egregious vanity.”Robert Hunt, quoted in Myrone 32.

But in 2014–15, William Blake: Apprentice and Master presented an artisan who labored to master difficult processes—bearing no small resemblance to the curator, whose life work it has been to understand and to master the techniques used by Blake. Phillips is himself the producer of beautiful artisanal editions of Blake’s illuminated books, printed from reproductions of the plates. His prints eschew color to reveal the delicate linearity of the plates. The atmospheric exhibition design included a re-creation of Blake’s printmaking studio (painted in tasteful Farrow and Ball colors) and labels that looked like copperplates. The visitor was offered a journey into Blake’s private world via a total immersion in the world of the eighteenth-century print trade, a context that appeals to today’s fascination with the craft of the artisan. This re-creation was clean and elegant, a workplace without clutter or dirt, the rubbish cleared away “from a caves mouth.”

Physical versus virtual

“Nothing can tell us more about a work of art than the discovery of how it was made,” claims the catalogue, and this exhibition proved this to be true. In the process, it announced the superiority of the physical to the virtual object, whilst making movingly obvious its fragility: Phillips spoke at the accompanying day conference of the strict rules that limit movement and exhibition of Blake’s work and of the periods of rest required between outings.

Telling how Blake made his extraordinary works of art, and how Blake’s life made him, exhibition and catalogue establish a narrative through material objects, documents, places, spaces, techniques. This was not so much a story of ideas but of things, and as such it shows just how much cannot be conveyed through the virtual reality of the internet. The size of the objects, the texture of the monoprints, the effort of engraving, the size of Blake’s studio are all things that have to be seen in the flesh. The exhibition space offered an encounter with objects in a way that the internet cannot emulate: walking past the plates of Europe copy B laid out on a wall enforces a sequence and meaning that can be changed simply by walking the exhibition room anticlockwise rather than clockwise.

Apprentice and master

On one level, the subtitle “Apprentice and Master” is simply descriptive, explaining a focus on three main periods of Blake’s career: the apprenticeship to Basire; the 1790s, when he was a “master artist-printmaker and technical innovator”; and the last years of his life, when he “inspired a group of young artists and artist-printmakers known as the Ancients” (11). It creates a focus on learning, tradition, even deference to authority. Phillips repeatedly draws on Malkin’s 1806 testimony to present a Blake who learns to “collect and copy” engravings, is “given plaster casts to copy” (11). But Malkin’s Blake may be subtly aligned to the expectations of a bourgeois educationalist, even if one deeply sympathetic to Blake. The Blake familiar to much of the twentieth century believed that “the tygers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction.” It’s a revelation, then, to discover that Blake does indeed use the word “master” in an unexpected range of contexts. He repeatedly refers to Basire as his master (E 573-74) when he is writing about “Chaucers Canterbury Pilgrims,” and also insists that learning to draw is the only way to master engraving: “I defy any Man to Cut Cleaner Strokes than I do or rougher when I please & assert that he who thinks he can Engrave or Paint either without being a Master of Drawing is a Fool” (E 582). Blake does have a concept of the good master—whether Basire, or “our Divine Master” (E 728) in a letter to Butts. Los announces that he is master to Urizen in Jerusalem. It is clearly not the case that Blake thinks only of a Urizenic master, the “great Work master” (E 314) of The Four Zoas. In demonstrating this in Apprentice and Master (although he would not labor so obvious a point), Phillips rejects the implicitly Freudian or Bloomian model familiar to twentieth-century readers.

This exhibition and catalogue (implicitly) reject the idea of Blake’s lack of facility, touted for instance by Mei-Ying Sung’s William Blake and the Art of Engraving (2009), which took evidence of repoussage to tell a story of trial and error, of modification and struggle. Phillips instead establishes Blake’s skill, whether in mirror writing, engraving, or monoprints, skill won by hard study and determination. Emphasizing success rather than failure, Phillips presents Blake as “Master of His Trade”—at the least from 1785 to 1791, his achievement evidenced by Boydell’s 1787 commission for engraving Hogarth’s painting of The Beggar’s Opera. Whereas the apprentice Blake learns by copying, the adult Blake attains technical mastery through tireless repetition: “Over time, as he became more accomplished, such mock-ups would have been needed less” (94). “By 1789, when he etched the plates of Songs of Innocence and The Book of Thel, imperfections are still to be found, but the mirror writing technique has been all but mastered” (96). Reengraving his 1773 plate of Joseph of Arimathea in the last decade of his life, he demonstrates this mastery: “When set against the image printed from the same plate after Blake had reworked it 45 or more years later, the difference between an apprentice piece and the work of a master is unmistakable” (35). The concept of “master” is here internalized: mastery is realized alone.

Minute particulars

The substantial catalogue by Phillips (with chapters on the Ancients by Martin Butlin and on Palmer, Calvert, and Richmond by Colin Harrison) is a major contribution to Blake scholarship, built up from laborious archival research. Similarly, the exhibition was very strong on context, full of the kind of works that Blake saw and knew. But for this reason, the significance of objects was not always obvious at first glance. Documents such as the record of an apprenticeship to Blake for Thomas Owen in 1788 (84) released their meanings only through commentary. Rejecting the tendency of Tate Britain’s current hang to offer the visual without contextualizing words, the exhibition offered visual proof of discoveries explained in labels and catalogue. Small details and differences reveal a lot. Phillips shows how the young Blake’s work for Basire recording monuments of the kings and queens in Westminster Abbey led to six additional drawings in which “small but significant adjustments” allowed Blake to imagine the dead figures alive, turning monument into portrait (45). Often the exhibition achieved just this miracle, allowing old documents to come alive. Just occasionally, this focus can be misleading. Phillips imagines that Blake would have seen Dr. William Hunter address “the minute particulars of the human anatomy” at his lectures (49). But as he notes later on (105), Blake’s beliefs were fundamentally opposed to empiricism. For Blake, “minute particulars” probably represented something quite different from the “partly dissected corpses of criminals executed at Tyburn” that Hunter used (55). John Barrell suggested that we misread Blake’s concept of individuality: “For Blake as for Barry, the sublimity of art is the result of the representation of generic character, and if ‘All Sublimity is founded on Minute Discrimination’, that is because, for both men, the representation of different classes or characters, finely organised and so finely discriminated from each other, is the representation of the ‘sublime.’”John Barrell, The Political Theory of Painting from Reynolds to Hazlitt (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986) 238. Blake’s minute particulars may be closer to the “Minute Discrimination” (E 643, 653) that mark out eternal character in his annotations to Reynolds’s Discourses. The methodology so brilliantly embodied in catalogue and exhibition is empirical, but the occasional downside is the inability to resist the lure of a possible source: “It is just possible that he may have seen examples of Castiglione’s monotypes in the Sagrado sale, if they were included” (150). If everything is learnt (rather than imagined as by Tate’s Blake), then all innovation must have a source. In the end, Linnell becomes master to Blake: “The experience of seeing fine impressions of the Old Master engravers, together with working with Linnell on his plates, probably also inspired Blake to rework other examples of his earlier separate plates engraved on copper in intaglio” (190). Every change must come from someone.

Houses and spaces

One of the most satisfying features of the Ashmolean exhibition is necessarily lost in the catalogue (though this contains marvellous material on Blake’s Lambeth home and his final apartment at Fountain Court). The layout took the visitor through spaces of very different dimensions—from a tunnel and bridge through a long, dark gallery, to a high central room with a re-creation at one end of Blake’s studio to the dimensions and in the layout that Phillips has recovered. In doing so, it made the visitor newly aware of the space of the exhibition room and its difference from Blake’s places of making and exhibition, such as the room upstairs in the house he grew up in. (The Tate version of the 1809 exhibition did not re-create the dimensions of the upstairs room at his brother’s hosiery shop, though blank spaces marked out missing works, including the lost painting The Ancient Britons as a huge ghost image on one wall.) Although it was not unusual in Blake’s time to show work in a private home (Gainsborough, Romney, and Turner all used the first floor of their houses to exhibit their work), the Ashmolean show was surprising in its ability to convey a sense of rooms, spaces, and documentary contexts in a way that was moving and intimate.

The final chapter of the catalogue tells how Blake’s artist friends recall the image of Dürer’s “Melencolia 1” in work they produced around the time of Blake’s death. These images, Phillips shows, are recollections of Blake at his engraving table, for “on the occasion of their visits to Fountain Court, the Ancients had each seen Blake at work at his engraving table, and ‘close by’, as Palmer remembered, Dürer’s Melencolia I ” (246). The achievement of this exhibition and catalogue is to show how the labor of engraving gave birth to images like “Los howld,” images that can no more be forgotten than the figure of their creator bent over his work table.