William Blake and the Age of Aquarius. Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University, 23 September 2017–11 March 2018.

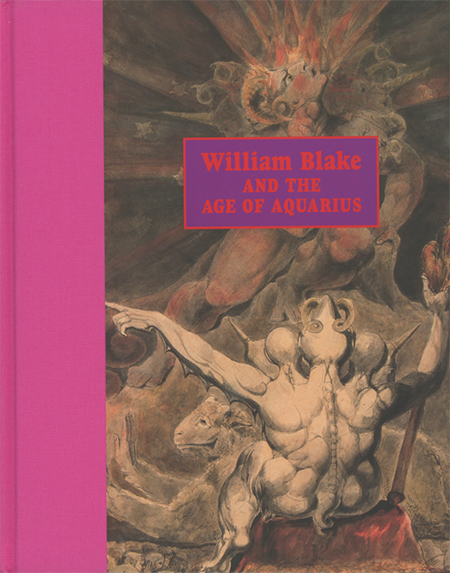

Stephen F. Eisenman, ed. William Blake and the Age of Aquarius. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017. xii + 232 pp. $45.00/£35.00, hardcover.

Jennifer Davis Michael (jmichael@sewanee.edu) is professor and chair of English at the University of the South in Sewanee, TN. She is the author of Blake and the City (Bucknell, 2006). Her current project is called “Poetry at the Edge of Silence.”

“Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive, / But to be young was very heaven!” Thus Wordsworth looked back at the heady days of Paris in 1789 from the vantage point of 1805. Such nostalgia, of course, is a hallmark of Romanticism. Nor is it a simple recollection, but a multilayered process of memory: in this case, Wordsworth looks back at a time of looking forward, much as Blake writes in 1793 a “prophecy” of America in 1776. Then there is the memory of memory, as in Wordsworth’s “Tintern Abbey,” where the speaker remembers how a remembered scene has sustained him in the intervening five years. In the 1799 Prelude, he turns back to his earliest memories—“Was it for this?”—in an attempt to resolve his writer’s block. Looking backward in order to move forward is a quintessentially Romantic exercise, one complicated further by the uncertainty of imagining what “might will have been,” as Emily Rohrbach has shown (2).

Such was the case when I visited William Blake and the Age of Aquarius at the Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art at Northwestern University, curated by Stephen F. Eisenman. The exhibition explored how and why Blake became a role model for artistic revolutionaries in postwar America, building up to the countercultural upheaval of the 1960s. But this was not a straightforward study of one-way influence in which Blake served as background. In the catalogue, Lisa G. Corrin, director of the Block Museum, expresses “hope that seeing Blake against the backdrop of the ‘Age of Aquarius’ will enable us to reconnect to the radicalism of this iconic figure and to find in his multidimensional contributions meaning for our own tumultuous times” (vii). As Eisenman adds, “the products of both periods are potentially valuable resources for social movements still to come” (6). In a Romantic act of meta-recall, this exhibition recalls the recollection of Blake. Back in 1995, Morris Eaves referred to Blake’s perennial status as “the sign of something new about to happen” (414). That “something new” begins, as ever, with a Romantic glance backward.

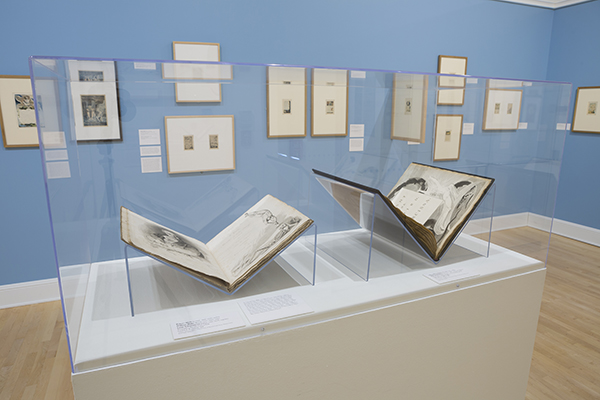

The more than fifty Blake prints came from a variety of sources, including the Yale Center for British Art, the Rosenbach in Philadelphia, and Northwestern’s own Charles Deering McCormick Library, which also supplied a number of the posters and other material from the 1960s. The exhibition occupied five rooms on the airy second floor of the museum’s modern glass building beside Lake Michigan. In the foyer, visitors encountered a large reproduction of the frontispiece of Europe with a brief introduction. The first room of the exhibition proper was an immersion in Blake.

© Clare Britt Photography. See enlargement.

One of the most interesting aspects of this room was the arrangement of Blake’s seven Dante engravings above a series of images from copy H of Visions of the Daughters of Albion, a juxtaposition intended to counter the assumption that Blake’s radicalism faded with age. While the placard pointed predictably to the depiction of the lustful in Inferno 5, who seem far from tormented in Blake’s rendition, I was even more interested in how the bodies of Dante’s thieves often mirror the tortured and twisted poses of Bromion and Theotormon in the earlier work.

In a small room to the left hung a complete set of Job illustrations from Eisenman’s collection. The connection to the Age of Aquarius seemed somewhat tenuous: the placard mentioned how, for Blake, the only “true religion” is that which honors the body and its impulses, yet the Job illustrations don’t celebrate energy in the way that, for instance, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell does. There might have been an opportunity to probe further into the biblical underpinnings of revolution and “infernal reading,” perhaps through Allen Ginsberg and his use of Moloch.

I initially went the wrong way upon leaving this room, turning the corner by the watercolor The Number of the Beast Is 666 to enter the psychedelic room, with Rick Griffin’s poster for Kenneth Anger’s film Lucifer Rising making an obvious, if abrupt, connection. What I should have done, however, was turn right from the first room into a room displaying visual artists’ responses to Blake from the 1940s on, especially the journal Tiger’s Eye and artists’ books by Kenneth Patchen and others. I know how difficult it is to light these galleries, but I did find that glare made it hard to view some works, such as Ad Reinhardt’s screen prints, which at first appeared solid black.

The artists of the 1940s seem to have been primarily interested in reproducing Blake’s method of printing and/or the visual effect of his composite art. For instance, Stanley William Hayter at his workshop, Atelier 17 (relocated from Paris to New York), experimented with various methods of color printing. He collaborated with Ruthven Todd to reproduce Blake’s method of relief printing. As Eisenman notes, “They largely got it wrong, supposing Blake used a transfer process in order to avoid writing backwards” (44). Still, the resulting portfolio of prints based on short poems by Todd is engaging, and it demonstrates further that it was not only Blake’s revolutionary ideas that attracted these followers. His method of combining word and image on a single plate and in a single process spoke to the abstract expressionists. As much as Jackson Pollock and Reinhardt differ in style from Blake and from each other, they share certain aesthetic principles. As Clifford Ross puts it, “Abstract Expressionist images invoke; they do not depict. They confront; they do not describe” (18). Like Blake, these artists are engaged in “a heroic, one-on-one confrontation with the subconscious” (Ross 18). While Blake’s visual works are, of course, more representational, they also reveal an awareness of the limits of representation.

Other works in this room, moving forward into the 1950s and 1960s, reflected a more thematic Blakean influence. Diane Arbus published a series of photographs in Harper’s Bazaar called Auguries of Innocence, captioned with lines from Blake’s manuscript poem of that title. According to Eisenman, these photos, published in the wake of John Kennedy’s assassination in 1963, evoke “the national mood of lost innocence” (72). The artist Jess engaged in deliberate Blakean appropriations in a variety of media, such as an oil painting entitled Salvages VI: Rintrah Roars …, with paint so thick that it becomes almost sculptural, like a bas-relief, and an untitled “paste-up” featuring a shepherdess and her flock decorated with speech bubbles, some from newspaper clippings and others simply articulating “No! No! No!” or “Universal YES!”

Jay DeFeo’s The Rose incorporates elements of the Europe frontispiece as well as “Albion Rose.” The Rose is an enormous canvas upon which the artist layered paint, mica, and wood, up to a foot thick in some areas (Ferrell, catalogue p. 120). While the exhibition did not include this 1800-pound painting (Whitney Museum), it did include a study for it (a graphite and gelatin silver print on paper), as well as Wallace Berman’s photographs of DeFeo naked in front of it.

More compelling to me than The White Rose was what I call the psychedelic room. This room was truly multimedia, with more of an emphasis on musical responses to Blake. Using headphones, visitors could listen to renditions of Songs by Ginsberg and the Fugs.

Just outside this haven of audiovisual escape was a wall full of concert posters for the Doors, the Yardbirds, the Grateful Dead, and others. I wondered whether the psychedelic “melting letters” so characteristic of 1960s typography were meant to mimic a drug trip or the vegetative letters of Blake. Victor Moscoso, who designed many of these posters, studied with Josef Albers at Yale. So did Richard Anuszkiewicz, from whom we have a portfolio of screen prints entitled Inward Eye, each of which the artist captioned with text from Blake.

Finally, a smaller video screen in the main psychedelic room featured film clips of the 1968 riots in Chicago. The juxtaposition with the other videos led me to ponder the contrasting modes of resistance: retreating into vision or engaging in direct action. I appreciated the way the exhibition did not settle this question, but rather allowed the footage to stand as another artifact from the Age of Aquarius.

The associated publication bearing the name of the exhibition is not a catalogue in the usual sense—a list of all the objects in the show. I wish that it were. Nevertheless, it is a handsome, high-quality volume with color reproductions of many of the visual works, so that those who missed the exhibition can still experience much of it vicariously. It also reproduces other Blake works not included in the show and provides crucial interdisciplinary context for students of Blake who might be unfamiliar with the Aquarian counterculture, and vice versa. Eisenman’s general introduction (from which I have already quoted) deftly begins with the San Francisco “flower children” as heirs of Blake’s roses and sunflowers, then presents a brief but effective introduction to Blake’s “Life and Times” and to his art, concluding with “The American Blake Revival” via Whitman, Ginsberg, and Frye, which forms a bridge to discussion of specific works.

Other articles in the volume provide a variety of depth and range. Mark Crosby’s “Prophets, Madmen, and Millenarians” usefully situates Blake in the context of various radical subcultures, while acknowledging that his work has been adopted by establishment forces as well.Unfortunately, Crosby repeats the error in Leo Damrosch’s Eternity’s Sunrise that a Proverb of Hell graces the walls of Donald Trump’s library (80). See my “Blake, Trump, and the Road of Excess: An Urban Legend.” Elizabeth Ferrell’s “William Blake on the West Coast” delves deeply into a specific subgroup of artists and writers who began to discover Blake in the late 1940s. The interplay between the Beat poets and such visual artists as DeFeo and Conner is especially rich. Jacob Henry Leveton’s “William Blake and Art against Surveillance,” a shorter article, is also more critically sophisticated, less a historical overview than a layered reading of Blake’s method of color printing (exemplified in The Book of Urizen) as a prototype for the work of the abstract expressionists, such as Pollock and Reinhardt.

Two other articles probe the corners of Blake’s influence: John P. Murphy’s “Building Golgonooza in the Age of Aquarius” elaborates on a little-known commune that existed outside Athens, Ohio, from 1969 to 1986. This Church of William Blake was meant to serve as “the aesthetic equivalent of Noah’s ark” in the darkened world of the Cold War (161). Crosby’s second article, “Sendak, Blake, and the Image of Childhood,” focuses on the popular children’s author and his visual and thematic engagement with Blake, amplifying the few examples in the exhibition. (On a personal note, as one born in 1967, I can say that Sendak was a formative influence long before I encountered any Blake—or Ginsberg or the Doors, for that matter.)

W. J. T. Mitchell’s brief “Blake Now and Then” forms a fitting epilogue to the volume, especially if one recalls his 1982 essay “Dangerous Blake,” in which he predicted several areas in which Blake studies might soon venture. One of those areas, the question of madness, has particular bearing on the 1960s, with its embrace of such epithets as “crazy” and the emergence of Mad magazine (202). But Mitchell also explores the slipperiness of temporal categories with regard to Blake. In some ways, Blake may have seemed to belong to the “now” of the 1960s more than the “then” of the 1790s, but we are in a “now” half a century later, when the “summer of love” seems a naïve figment of dreamy Beulah. Perhaps the lesson, however, is that resistance and revolution always appeal to nostalgia, as the word radical refers to roots. As another Mitchell, Joni, sang, “We are stardust / We are golden / And we’ve got to get ourselves / Back to the garden.” That song itself looks back to a moment of anticipation before collapsing that time into the Woodstock Festival, an event that Joni Mitchell did not attend. And I, born in the late 1960s but always fascinated by a culture I cannot quite remember, found myself back on a campus where I had begun my serious study of Blake in the early 1990s, watching current Northwestern students, a further generation removed, as they encountered Blake, Hendrix, and Ginsberg all at once. A Golgonoozic moment indeed.

Works Cited

Blunt, Anthony. “Blake’s ‘Ancient of Days’: The Symbolism of the Compasses.” Journal of the Warburg Institute 2.1 (1938): 53-63.

Damrosch, Leo. Eternity’s Sunrise: The Imaginative World of William Blake. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015.

Eaves, Morris. “On Blakes We Want and Blakes We Don’t.” Huntington Library Quarterly 58.3/4 (1995): 413-39.

Kintner, Amy. “Back to the Garden Again: Joni Mitchell’s ‘Woodstock’ and Utopianism in Song.” Popular Music 35.1 (2016): 1-22.

Michael, Jennifer Davis. “Blake, Trump, and the Road of Excess: An Urban Legend.” Millions 16 June 2016.

Mitchell, W. J. T. “Dangerous Blake.” Studies in Romanticism 21.3 (fall 1982): 410-16.

Rimanelli, David. “Beautiful Loser: Op Art Revisited.” Artforum International 45.9 (May 2007): 312-27.

Rohrbach, Emily. Modernity’s Mist: British Romanticism and the Poetics of Anticipation. New York: Fordham University Press, 2016.

Ross, Clifford, ed. Abstract Expressionism: Creators and Critics. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1990.

Traps, Yevgeniya. “Romance of the Rose: On Jay DeFeo.” Paris Review 14 May 2013.