Gerald Eades Bentley, Jr.

23 August 1930–31 August 2017

Karen Mulhallen (karenmulhallen@rogers.com) is professor emeritus, Ryerson University.

He who would do good to another, must do it in Minute Particulars Jerusalem pl. 55

I had been thinking of JerryDonations in his memory may be made to the Victoria University Library, where Jerry’s Blake collection lives on. <http://my.alumni.utoronto.ca/GEBentley> all Thursday after I received an e-mail from his daughters, Sarah and Julia, on Wednesday afternoon, 30 August, telling me he had taken a turn for the worse and that Sarah was flying to Toronto and Julia had canceled her trip to take her daughter, Anjali, to Vancouver to begin university at UBC. I checked my e-mail constantly that day and was unable to focus. Friday at noon came the news of his death. Death by e-mail.

I had written and spoken to Jerry occasionally over the brief summer while he was at the family cottage in Dutch Boys Landing, Mears, Michigan, and I had phoned as I always did to wish him an early happy birthday. It was then that I learned of his fall and that he was in hospital waiting to come back to hospital in Toronto, where he could begin rehabilitation.

I met the irresistible force who was Jerry Bentley, a.k.a. GEB, in the fall of 1973, when I audited his graduate course in eighteenth-century book illustration. My own PhD thesis was well under way, I had a wonderful and supportive advisor, poet and bibliographer Douglas Lochhead, and I was embarked on a journey through early twentieth-century private presses. I had already learned how to set type, had worked on wooden presses, and had published some of my printing, but I was teaching fulltime, and coming to grips with my thesis was difficult. I told myself what I needed was an immersion in an area related to my academic subject, and although I was a modernist I thought the eighteenth century was not so very far away.

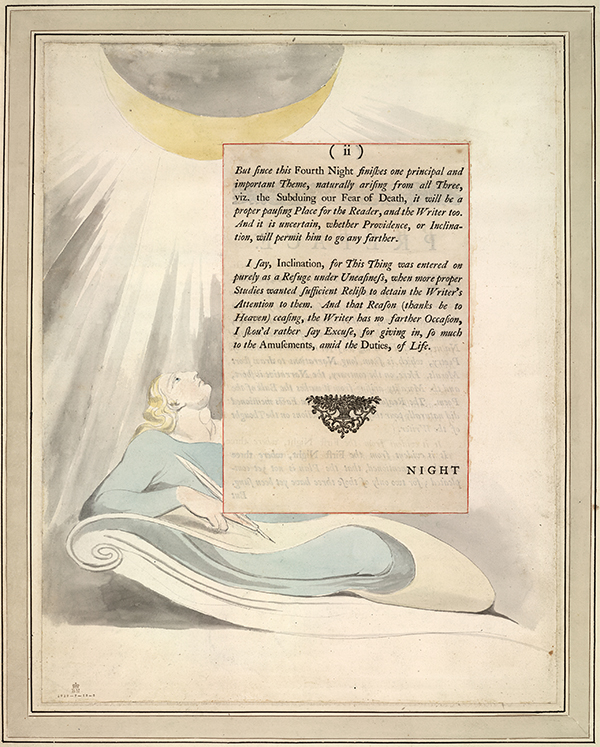

I quickly learned that passive observers were not the order of the day in GEB’s graduate seminar, and after a month he pointed a finger at me and said, “Ms. Mulhallen, as your contribution for this experience you will make a presentation in three weeks on Blake’s Night Thoughts.” I had no idea what he meant by Night Thoughts—my only knowledge of Blake’s illustrations was for the Songs of Innocence and of Experience, and the Night Thoughts drawings had not been published, except as microfilm and slides.

Over the next weeks, between my fulltime lecturing downtown and my work as an editor on two magazines, I made my way to the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library with a notebook in hand and I looked at 537 slides of Blake’s Night Thoughts watercolors. I was pretty unhappy when I discovered the scale of the assignment, which of course made me determined to succeed. When the day for my presentation arrived, the seminar was transferred to the Fisher Rare Book Library and the deed was done.

Afterwards GEB invited me back to his office and asked me about my thesis. He suggested I ought to change my topic. I was terrified and spoke both to my advisor and to another of my graduate professors, the great Bloomsbury scholar S. P. “Pat” Rosenbaum. Neither of them hesitated—“Do it,” each said. “Bentley is the world’s greatest Blake scholar and Blake is one of the English language’s greatest poets. Just do it.”

Later I would learn what was meant by “Bentley is the world’s greatest Blake scholar,” a scholar who almost singlehandedly shifted the focus of Blake criticism from formalism and symbolism to the minute particulars of Blake’s life and work, to the metals and papers of his books, and to the historical context in which he developed his art. But my learning about the extent of GEB’s work—his ongoing passion—and his curiosity and generosity only occurred as I worked on my own Blake project.

One of the many extraordinary aspects of GEB was his physical appearance. There was no other English professor at the University of Toronto at that time who in any way resembled him. He wore a cape and had a shirt with lace cuffs. He was tall and handsome with a regal bearing and a clipped beard, and by the time I met him his hair was a yellowish white, although I think when he was a very young man it had a reddish hue. One of his colleagues said GEB looked like Blake’s Job. Another compared him to General Custer, yet another to Colonel Sanders. I think in general his appearance inspired awe. Even in the last few years he was always meticulous in his dress. At one of his monthly teas recently he was dressed in an impeccable pink dress shirt, which showed admirably against his white hair and beard. Late one 2017 winter afternoon I visited him and he greeted me at his door dressed in a Chinese scholar’s robe.

I had no idea why GEB chose me forty-four years ago for the Night Thoughts task, as I had no eighteenth-century courses and I would have to make them up for my doctorate, as well as conjure a new proposal and travel the world to do the thesis. And as GEB himself said, “The Night Thoughts is a sinkhole.” Nonetheless, I said yes, frightened as I was, and in the summer of 1974 I went to England to see Blake’s actual Night Thoughts drawings.

When I returned from the British Museum Department of Prints and Drawings that summer, GEB in effect, but cunningly, set a thesis chapter timetable for me. And he did it by bribing me. I was lecturing fulltime, so only evenings and weekends were possible for writing. I became a ghost in my university office, the staff refrigerator held my supper, and I went home, my own private hotel, only to sleep. The bribes were transparent. For example, GEB would say, “If you finish that section by next Friday, I will give you such and such a book.” Since I had no Blake books, and like all scholars was book amorous, if not book omnivorous, I would succumb. I would write through the night, hang a bag of paper on the Bentleys’ front doorknob, and paddle down to my university. At 5 or 6 p.m. I would go back to the Bentleys’ to pick up my chapter. My fellow graduate students often waited weeks on end for their advisors’ replies, but mine were ready the same day. Beth would often say to me, “You haven’t eaten, come in and eat before you leave.” And so the relationship, the friendship, grew. I was no longer frightened—instead, I was caught up in the irresistible Bentley force.

Within the year, I was ready to submit. Jerry and Beth were in India, and I was on my own with the thesis committee. Some revisions were demanded. There was some consternation over my thesis length, the size of three Toronto telephone books, and it was suggested by more than one committee member that this was typical of Bentley.

But GEB was one of the ever-prolifics (Jerusalem pl. 73) of Blake’s world. He was always at work on a new book or even two, finishing many articles, compiling an annual checklist of everything published on Blake, conducting meetings and exchanges by e-mail and snail mail and telephone with scholars throughout the world. Constant productivity, continuous curiosity, endless generosity.

After that first summer of studying Blake in England, my travels in Blake often overlapped with the Bentleys’, for Jerry and Beth traveled the world together with Blake by their side. They lived in North Africa, in France and in England, and in India. They went annually to the Huntington Library and Art Gallery in California. They made friends worldwide, and those friendships have been maintained over the decades. Life for Jerry and Beth was a great adventure, and they were generous in taking me along. One year I gave a paper in California at the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies. GEB no longer gave papers, but he generously prepared one so he could present with me in my session. Then he and Beth and I ate dinner on the docked Queen Mary.

I spent a month with Jerry and Beth when they were living in Australia. I went to a party that his graduate students at the military college in Canberra threw for them, but we also explored southeastern Australia together. We visited a sheep ranch, rode horses, searched for books in the outback, watched kangaroos and anteaters, and went to the Sydney Opera House.

As GEB’s eightieth birthday approached, I began to muse on the festschrift edited by Alexander Gourlay, Prophetic Character: Essays on William Blake in Honor of John E. Grant (Locust Hill, 2002). Why not a festschrift for GEB, I thought? Surely he, who has been so dedicated to enabling the work of others, to building an ideal community of scholars, should be celebrated? The time was short, but in the spring of 2009 I asked GEB whom he considered the most promising scholars writing on Blake. I went home and wrote to each of them immediately, and simultaneously sent in a proposal to the University of Toronto Press. I began to plan a symposium and, in collaboration with Robert Brandeis, then head of the Victoria College Libraries, a Blake exhibition accompanied by a catalogue. I had to raise approximately $40,000 to finance the books’ pictures and other costs associated with the events, but three of my own graduate students signed on to help, and every scholar to whom I wrote also signed on, promising an essay and often helping with the editing of the volume. The book and the events were to be secret gifts, and I managed to keep it all from GEB until the book was listed in the University of Toronto Press catalogue. I remember the afternoon in December 2009 and the soft winter light in Jerry and Beth’s living room. I had come over for a late afternoon drink, my little dog, Matilda, had climbed up on Beth’s lap from the footrest on her wheelchair, and Jerry was talking to me about some very interesting finds in his annual compilation of Blake studies for Blake. “Here’s a book you’ve missed,” I said, as I showed them the listing for Blake in Our Time: Essays in Honour of G. E. Bentley Jr. And so in the summer of 2010 scholars came from all over North America, Europe, and Asia to celebrate the irresistible force, G. E. Bentley, Jr. Papers, musical performances, a banquet, an exhibition, a catalogue, and a book of essays. Happy eightieth birthday, Jerry, from us all.

Like Blake and Catherine, Jerry had an extraordinary helpmate in Beth. She managed her own scholarly activities while supporting not only GEB and their family but also their enormous adopted family. After her death in 2011, he not only continued her monthly teas, which they had called “Beth’s Fourth Monday at Home Teas,” but also continued to write, including his annual checklists for Blake of all the publications on Blake, as well as a family memoir. Over the past few years, we often discussed the family memoir, as well as his travels in the Blake world, his friendships with other scholars, and the extraordinary collectors he encountered. He was a great storyteller, and often regaled guests at the monthly teas with accounts of some of his and their adventures. He continued to say we this and we that as if Beth were still alive with him, right there in the room. And perhaps she was. Although he never said so to me, I felt he had enjoyed his life immensely.

Two years ago, two friends held a small birthday dinner for me. It was intimate, only six at table. GEB was there, and he brought me a poem as his gift. It’s a poem about aging, and “the satisfaction of work well done.” The joy “in the discovery of the perfect word.” The recognition that “tomorrow is not forever,” that “three hours sleep is an accomplishment / As is the work one may do then.” But Beth’s presence enters the poem most movingly with the poet

Finding that the head beside me,

Sleeping on my arm in the wide bed,

Is my cat’s, not my Beth’s.

In the preface to his acclaimed 2001 biography of Blake, The Stranger from Paradise, GEB speaks of his intimate relationship to his subject: For half a century I have been wrestling with the spirit of William Blake, with the protean shapes of Blake’s myth and the factual Laocoon of his life. And I have enjoyed it all. If I could believe that this biography is worthy of him, I would feel that I had won his blessing. (xvii) I often think of this passage and the manner in which GEB himself has given to each of us—his friends, his students, his colleagues, his fellow travelers—his continuous blessing.