Like so many others, I have Allen Ginsberg to thank for introducing me to the idea that Songs of Innocence and of Experience are poems meant to be sung. When I was a sophomore, he visited my university and, after performing many of his own poems, he launched into a rendition of “Nurse’s Song” (Innocence). Accompanying himself on the harmonium, he spoke-sung the nurse’s part, then climbed into a thready falsetto for the children’s voices, and concluded with a rousing “And all the hills ecchoéd” that he repeated for what must have been five minutes, drawing the crowd into chanting it, trailing off at the end into a near-silent prayer.For a rendition with a fuller orchestration than the one I was treated to, see <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Y81kFrHb08>. It includes Peter Orlovsky and Greg Corso on vocals and features some excellent yodeling. Afterwards, I mustered the courage to ask him about singing Blake, and he confirmed that Blake had in fact sung the Songs, though no record of the arrangements survives.

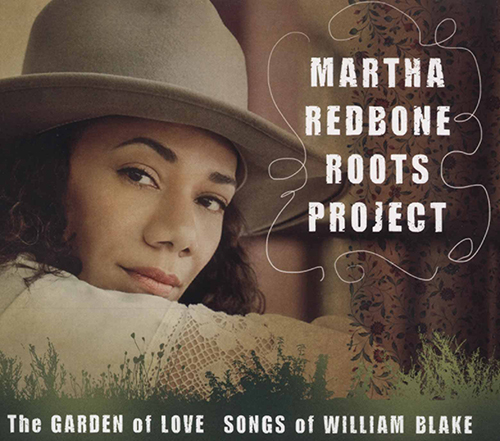

Over the years, I have heard many other takes on the Songs, from Benjamin Britten’s intense art songs to the industrial calypso Cockney (I think that accurately describes it) of Jah Wobble’s “Tyger Tyger.”For a useful compendium and guide to many musical takes on Blake, see Jason Whittaker and Roger Whitson’s Zoamorphosis, especially the Blake Jukebox <http://zoamorphosis.com/category/jukebox>. For a revealing history of the musical setting of “Jerusalem” (the confusing title used for “And Did Those Feet in Ancient Time” from the preface to Milton), see Michael Ferber, “Blake’s ‘Jerusalem’ as a Hymn,” Blake 34.3 (winter 2000-01): 82-94. It includes a brief but useful discography. The breadth of styles attests to the vitality and accessibility of the verse and the vision behind it. Given Blake’s stress on the individual’s right to interpretation, it would seem un-Blakean to insist that one style truly captures Blake and to rule the others out of court. But I don’t think it’s invidious to say that I now have the Martha Redbone Roots Project’s deep and powerful The Garden of Love to thank for reintroducing me to Blake’s lyrics as songs to be belted out, crooned, and ruminated upon.

In the press release for the album, Redbone identifies it as “Appalachian folk and blues, what we would call music from the holler.” Yet if the music is old timey, this is not a sepia-toned period piece. This is living music, transporting the incisive ethical and political critique at the heart of Blake’s imaginative vision to an Appalachian landscape “radically altered by strip-mining”; Redbone, of Native American and African-American ancestry, finds in Blake a congenial voice for her own thoughts about “my ancestral home Black Mountain, Kentucky, coal country and pre-contact Shawnee/Cherokee land.” Given her rural commitments, it is not surprising that we do not get here the urban scenes of “The Chimney Sweeper” or “London.”For “London,” I’d recommend Sparklehorse’s haunting rendition; like Redbone, the late, lamented Mark Linkous had roots in coal-mining country. See the EP Someday I Will Treat You Good and <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zlWb1BV4Qmw>. What she gives us instead is a vivid collection of songs from Songs, the Notebook, and Poetical Sketches. Redbone herself wrote the music, along with Aaron Whitby and John McEuen (of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band); McEuen is also a co-producer and a key musical presence, contributing virtuoso performances on string instruments from the banjo to the fiddle to the lap dulcimer. Redbone and her team are not the first to adapt Blake to a folk or roots idiom; for one example, Greg Brown’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1986) will be known to some (reviewed in Blake 23.2 [fall 1989]: 96-98). But while that album has its moments (“The Little Vagabond,” for instance), it comes nowhere near the force and inventiveness of The Garden of Love, which frequently makes the listener feel as if these lyrics were somehow written with this music and this singer in mind.

The album opens with an unassuming figure on the keyboards, the shaking of a rattle, and a bluesy lick on the dobro—then comes Redbone’s electrifying voice in full throat, a prophet demanding our attention: “I laid me down upon a bank / Where love lay sleeping / I heard among the rushes dank / Weeping Weeping.” The music then assumes a regular melody and beat, laid down by Byron House’s thrumming upright bass, and Redbone moves to the next stanza from the Notebook and on to “The Garden of Love” proper, which is punctuated by Native American yips and chants. She gives eloquent voice to the speaker’s situation, articulating her bewildered pain as she searches for a place where she can realize her needs but finds only grim priests “binding with briars, my joys & desires.” The yearning in the last line is underscored by the backing vocals, and the closing, mournful repetition of “I went to the garden of love” recapitulates the tragedy while suggesting that this speaker has not given up.

The title track is a highlight but hardly the only one. It is clear from her delicate rendering of “How Sweet I Roamed” that Redbone can fully inhabit the tender and often wounded naïveté of Innocent voices; the lilting melody matches well with the unsuspecting speaker who stumbles into the traps of “the prince of love,” the pathos heightened by the repetition of the last line, which is delivered without harmonizing voices: “And mocks my loss of liberty.” “The Fly” showcases Redbone’s vocal range, its simple and affecting melody punctuated by McEuen’s expert guitar picking (though the sample of children at play strikes me as gratuitous) and strumming on the autoharp. Redbone’s take on this song of Experience is a persuasive rendering of an Innocent speaker’s becoming conscious of his own mortality and accepting it without losing his joy. She switches to a more prophetic voice in “I Rose Up at the Dawn of Day” from the Notebook, successfully transforming it into a rollicking gospel number, complete with tambourine, clapping, and chorus, which comes in on “Get thee away get thee away.” This seems just right for the Bunyan-like strangeness of these verses, mixing their familiar addresses to “Mr. Devil” with Blake’s preference for “Mental Joy & Mental Health / And Mental Friends & Mental wealth” as the speaker rejects the temptations of monetary wealth in order to “pray … for other People.”

That Redbone is able to adapt these verses so effectively is a great gift to her audience, and they seem like a natural match with the emotive power often associated with roots music. But what are its limits? The powerful authenticity of this genre can also tip into an embarrassing earnestness and simplemindedness that in this case might have given us a familiar image of Blake that often crosses into caricature—a goofy, big-hearted visionary who loved children and lambs and sex and who hated the Man in all his forms. One of the many problems with this flattening of Blake is that it cannot acknowledge the darker and more complex tones typically found in Experience, which might seem to lend themselves to more ironic styles—say, those of Brecht and Weill or Aimee Mann. But Redbone largely avoids this trap, and not just in “The Garden of Love.” In the spare setting of “I Heard an Angel Singing,” another poem from the Notebook, she gives equal time and weight to the angel who sings of “Mercy Pity Peace” as “the worlds release” and to the devil who acridly notes that “Mercy could be no more / If there was nobody poor.” More impressive still is “A Poison Tree,” which turns one of the best known of the Songs into a sly and swinging country waltz. There is a satisfied ring in her voice as the speaker surveys her poisoned “foe outstretched beneath the tree,” and it shows that Redbone is capable of giving expression to the deceitfulness (and self-deception) often found in Experience.

There are other tracks that don’t work quite so well, at least not for me. “A Dream” features a powerful Seminole chant by Lonnie Harrington, but there is something labored about the setting that is at odds with the reverie of the verse. “The Ecchoing Green” is sung completely without accompaniment; although Redbone’s voice is always worth listening to, the starkness here cuts against the communal pastoral joy of the poem. Finally, there is the recitation of “Why Should I Care for the Men of Thames” by Jonathan Spottiswoode, the English leader of the band Spottiswoode and His Enemies, with Redbone chanting and shaking a rattle in the background. I can see why verses that imagine the Ohio offering a rebaptism to counter the enslaving waters of “the cheating banks of Thames” would appeal to an artist who is looking to bridge the distance between Britain and America and who is keenly alive to the history of slavery: “I was born a slave but I go to be free.” However, the execution is hokey; although I like Spottiswoode’s other work, his delivery, both the bitterness of the first stanza and the hope in the second, is strained and compares unfavorably to the more richly modulated performances of the other tracks.

But the challenges posed by performing Blake are actually revealed more clearly by a track that succeeds on its own terms—“Hear the Voice of the Bard,” the “Introduction” to Songs of Experience. Backed by a bluesy guitar and harmonica, Redbone confidently voices the bard’s authoritative call, imploring the Earth to return. But we might say that this song is too confident; what’s missing here is the perspective that gives rise to “Earth’s Answer.” The Earth responds that the bard’s demand is unfair since she is bound by “Starry Jealousy”; indeed, it seems that she hears the bard’s would-be liberating voice as just another utterance from the oppressive “Father of the ancient men.” Perhaps Blake sees her as excusing herself from any responsibility for her “mind-forg’d manacles”; the Oothoon of Visions of the Daughters of Albion, for instance, refuses to conform to the patriarchal image of her as despoiled by her rapist. Yet even if this is true, it does not negate the fact that the bard seems much more interested in broadcasting his own authority and preaching repentance than in listening to whatever his audience might have to say. To be fair, Ginsberg doesn’t include “Earth’s Answer” in his album either, though, like Redbone, he is happy to adopt the bardic voice of “Introduction.” But Redbone’s willingness to recast the masculine bard in a powerful woman’s voice makes the absence of “Earth’s Answer” here feel like more of a missed opportunity. More broadly, “Introduction” and “Earth’s Answer” point to the limits of any single album of the Songs. No album could include them all, and this means that many of the complex interrelations among the songs will be excluded. That Blake rearranged them so frequently suggests that he kept discovering new ways they sang to each other. And then there is the absence of the illustrations integral to “Illuminated Printing.”

But we can, of course, look at the plates as we listen to these performances, and it would be churlish to dwell on what isn’t on the album, since so much is there. I have integrated The Garden of Love into my teaching of Blake and encourage others to consider doing the same; my students immediately get how Redbone’s adaptations illuminate the songs, make connections between Blake’s moment and ours, and open up new horizons in thinking about what and how Blake’s songs mean. I am grateful to her and to everyone involved in the album. I hope for a sequel.