George Romney and Ozias Humphry as Collectors of William Blake’s Illuminated Printing

Morton Paley (mpaley@berkeley.edu) is coediting The Reception of William Blake in Europe. His current research is on George Romney’s treatment of literary subjects.

The importance of the artistsI am indebted to Robert N. Essick and to Joseph Viscomi for generously sharing their knowledge with me, and to Sarah Jones for her indispensable assistance. Any errors are of course my own responsibility. George Romney and Ozias Humphry as collectors of William Blake in the mid-1790s has yet to be fully described and evaluated. Although Romney had told their mutual friend John Flaxman that Blake’s historical drawings “rank with those of Ml. Angelo,”Letter from Flaxman to William Hayley, 26 April 1784. See G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004) 31. This book will be cited as BR(2). his early acquisition of at least five (or four if the Songs are counted as one book) illuminated books was unknown until 1989.See Joseph Viscomi, “The Myth of Commissioned Illuminated Books: George Romney, Isaac D’Israeli, and ‘ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY designs … of Blake’s,’” Blake 23.2 (fall 1989): 48-74. Viscomi’s source is Collection of Pictures, Reserved after the Death of That Celebrated and Elegant Painter Romney, auction catalogue of Messrs. Christie, Manson, and Christie, Friday and Saturday, 9-10 May 1834. The sale included Visions, America, Urizen, and item 86x, “Blake’s two volumes,” which refers, as Viscomi shows, to the Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy A. Humphry’s role as a Blake collector has long been known, but most scholarly attention has been on his later relations with Blake, especially his obtaining for Blake the commission for one of the Last Judgment drawings (National Trust, Petworth) and eliciting a detailed written description of it in 1808,See The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman, newly rev. ed. (New York: Anchor-Random House, 1988) 552-54. This edition will be cited as E, followed by page number. rather than on his importance to Blake as a client earlier. Humphry commissioned two sets of images, mostly from illuminated books: the eight folio-sized prints known as A Large Book of Designs copy A, and A Small Book of Designs copy A (comprising twenty-three prints); he also purchased America copy H, Europe copy D, and copy H of Songs.See Bentley, Blake Books (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977) pp. 103, 146, 159, 356-57, 384, and 416. This book will be cited as BB. Bentley dates these purchases “about 1796.” See his “Ozias Humphry, William Upcott, and William Blake,” Humanities Association Review 26 (1975): 120. Songs copy H (Maurice Sendak Foundation), consisting of Songs of Experience only, is characterized by Viscomi as “one of four sets of beautifully color printed Experience plates [made] while Experience was still in progress” (e-mail communication). Romney acquired America copy A, The [First] Book of Urizen copy B, Visions of the Daughters of Albion copy F, Songs copy A, and a copy of Europe that has been identified as A.In an as yet unpublished paper (“Blake’s Printed Paintings”) that he has kindly allowed me to read, Viscomi argues in detail that Romney owned seven of the “deluxe set” (eight in all) of Blake’s illuminated books. The case is especially strong for Europe (A), since, as Viscomi demonstrates from physical evidence, it was produced as one of a pair with Romney’s America (A). Taken together, the two artists’ purchases compose a substantial portion of Blake’s known sales of illuminated books and associated material in the period from his initial prospectus “To the Public” (E 692-93), dated 10 October 1793, to 1796.

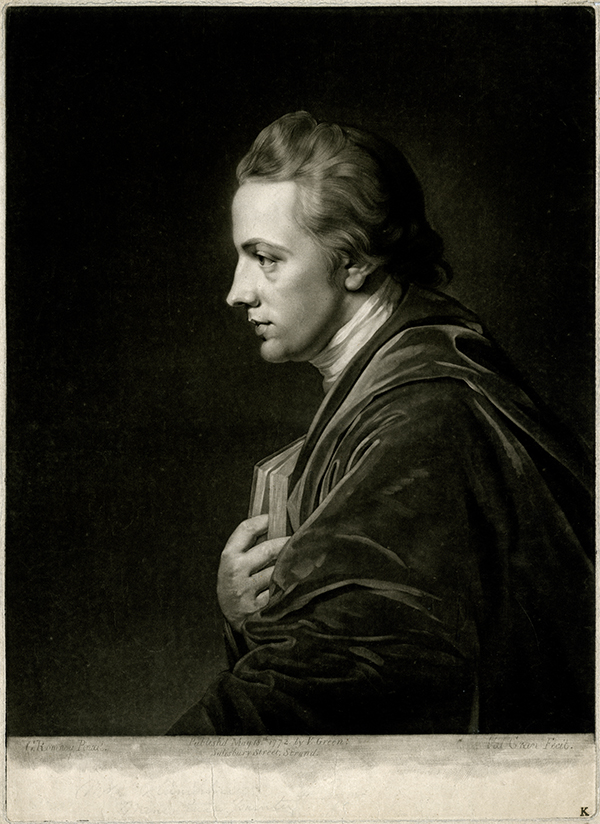

Romney and Humphry had been associated since the early parts of their respective careers in London. Each exhibited regularly at the Society of Artists/Free Society of ArtistsRomney exhibited at the Free Society of Artists from 1763 to 1769 and at the Society of Artists from 1770 to 1772; Humphry exhibited at the Society of Artists from 1765 to 1771. See Algernon Graves, The Society of Artists of Great Britain 1760–1791, The Free Society of Artists 1761–1783 (London: George Bell, 1907) 217-18, 125. and each sketched in the Duke of Richmond’s sculpture gallery in Whitehall. They painted each other’s portraits. Romney showed his friend in profile as a pensive-looking man holding a book to his chest, with one finger inserted to mark his place. This was to become the best-known image of Ozias Humphry: it was exhibited at the Society of Artists in 1772, engraved by Valentine Green (illus. 1) that same year, and again engraved by Caroline Watson in 1784.Family collection, Knole. Humphry also took Romney’s portrait (Knole, family collection). For this information I am grateful to Valerie Porter, estate office secretary at Knole.

After Sir Joshua Reynolds’s death in 1792, Romney succeeded him as the most sought-after portraitist in London. According to the famous wit and talker Richard “Conversation” Sharp, Romney was worth £50,000 in 1795.Farington, Diary, 8 December 1795, 2: 432. In 1793, despite the setbacks caused by the deterioration of his eyesight, Humphry took a house in Old Bond Street at an annual rent of 200 guineas,Farington, Diary, 18 October 1793, 1: 72. a considerable sum that may have strained his finances. Farington says that around that year Humphry asked Romney to lend him £200, and that Romney refused.Farington, Diary, 4 January 1797, 3: 738. Farington condemned Romney’s “peevishness” toward Humphry. He got this story from Nathaniel Marchant, a highly successful gem engraver, who had advised Romney and Humphry on what route to take on their Italian journey. Romney was well known for his liberality; after his death, Flaxman praised Romney’s generosity to him when a young sculptor and to others as well, writing, “I have seen him frequently relieve distress with a princely generosity.”Romney Collection: typescript, Morgan Library and Museum, call no. 917 R76, record ID 288571. However, in the mid-1790s Humphry’s behavior was at times unsettled and erratic.See Brewer 309-10. On 31 July 1796 Farington reported that Humphry had offended his patrons, the Duke and Duchess of Dorset: Humphry is quite out of favor at Knowle. He went to Knowle when the Duke was not there … and took possession of a room without previously shewing a proper attention to the Duchess. … The Duke is equally disgusted on some account. One charge is that He painted copies of Portraits at Knowle, & demanded payment for them as having been ordered by the Duchess, which she denied. (Diary 2: 624) He also enraged his friend (up to then) Sir George Yonge, when, after being introduced by Yonge to the Prince and Princess of Orange, he offered to paint their portraits as gifts, then billed the royal couple for them.See Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of Pastellists before 1800 <http://www.pastellists.com/Articles/Humphry.pdf>. Richard Cumberland later characterized Romney as “a man of a most gentle temper, with most irritable nerves.”Richard Cumberland, “Memoirs of Mr. George Romney,” European Magazine 43 (June 1803): 423 [417-23]. If Humphry asked for a loan in a manner that offended, Romney’s most irritable nerves may have overcome his princely generosity.

If Romney indeed refused to lend Humphry money, it seems unlikely that they were on terms that would have allowed them to visit Blake together. Each, as we will see, had to come at least twice, and each almost certainly did so without the other. How did they learn of Blake’s works? It is possible that one or both of them came across Blake’s 1793 prospectus or saw illuminated books displayed in the shop of the publisher and bookseller Joseph Johnson in 1794.For confirmation that Johnson exhibited some of Blake’s illuminated books in 1794, see Keri Davies, “Mrs. Bliss: A Blake Collector of 1794,” Blake in the Nineties, ed. Steve Clark and David Worrall (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999) 216-17. Also, there was a network of communication connecting these artists with their contemporaries. In this instance, the link is likely to have been Flaxman, who had been close to Blake for a long time. Not long after Flaxman’s return from Italy, in October 1794,See David Irwin, John Flaxman 1755–1826: Sculptor, Illustrator, Designer (London: Studio Vista, 1979) 53. he bought a copy of Songs of Experience from Blake (later combined with a copy of Innocence to form copy O of Songs of Innocence and of Experience), and he would have known what Blake had on offer.Flaxman may have purchased much more than that. In their sale catalogue of 25 June 1862, Willis and Sotheran advertised “A volume of extreme rarity, from the library of John Flaxman, the Sculptor, with his Autograph,” comprising America, Europe, Visions of the Daughters of Albion, The Book of Thel, and The First Book of Urizen, “5 vols. 4to. in one, half calf, £21.10s.” None of these has ever been located. They were again advertised by Willis and Sotheran in their catalogue of 25 December 1862. If these identifications are correct, Flaxman’s Blake collection rivaled Romney’s and Humphry’s. See Bentley, “Sale Catalogues of Blake’s Works: 1791–2013,” <http://library.vicu.utoronto.ca/collections/special_collections/bentley_blake_collection/sale_catalogue/1800.html>. Flaxman and Romney remained close until the end of Romney’s life: Romney painted John Flaxman Modeling the Bust of William Hayley (Yale Center for British Art) in 1795, and Flaxman wrote the section about Romney’s art in Hayley’s Life of George Romney.William Hayley, The Life of George Romney, Esq. (London: T. Payne, 1809) 305-13. After Flaxman’s return from Italy, he and Romney were neighbors as well as friends.See Arthur B. Chamberlain, George Romney (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1910) 195-96. The house Flaxman took after his return was at 6 Buckingham Street, Fitzroy Square. Romney lived at 37 Cavendish Square. Humphry was said to consider Flaxman “the greatest sculptor that had ever lived,” and, when challenged on this by the sculptor Joseph Nollekens, refused to retract his statement.John Thomas Smith, Nollekens and His Times (London: Henry Colburn, 1828) 2: 365. Nollekens, according to Smith, accused Humphry of “coddling close to him [Flaxman] at the councils” (presumably of the Royal Academy of Arts). Humphry drew a fine, sensitive pastel portrait of Flaxman (Lady Lever Art Gallery) in 1796. Blake’s first biographer, Alexander Gilchrist, wrote, with reference to the Songs, “Flaxman recommended more than one friend to take copies.”Alexander Gilchrist, Life of William Blake, “Pictor Ignotus” (London: Macmillan, 1863) 1: 124.

Blake evidently did not consider himself in need when he issued his prospectus of 1793, in which he had declared, “No Subscriptions for the numerous great works now in hand are asked, for none are wanted” (“To the Public,” E 693). In 1795 he was engaged in the illustrations for Edward Young’s Night Thoughts, a project for which he had great hopes and on which he expended tremendous energy, producing 537 watercolors and 43 engravings from 1795 through 1797. For the drawings he accepted the very low price of twenty guineas, no doubt on the expectation that his profit would come from the plates that he would engrave. There had then been no suspicion that in the end only the first part of the edition would be published, in 1797, and that it would be a commercial failure. There is no record of Blake’s being paid for the plates before Richard Edwards went out of business the following year.Bentley suggests that Blake may have been paid in copies of Night Thoughts that he and his wife could color and sell (William Blake in the Desolate Market [Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2014] 49-50). As Blake’s primary source of income was engraving, this meant the loss of a large sum that he expected to receive by 1797, not to mention his expectations for the future volumes, which would have left a considerable vacuum in his finances. By 15 August 1797 one of his customers, Dr. James Curry, could write to Humphry, “As poor Blake will not be out of need of money, I shall beg you to pay him for me, and to take the trouble when you return to town of having a box made for the prints ….”See Bentley, “Dr. James Curry as a Patron of Blake,” Notes and Queries 27.1 (1980): 71-73. (Although “the prints” are not named here, it is likely that one of them was the second impression of the first state of “Albion rose,”See Essick, The Separate Plates of William Blake: A Catalogue (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983) 25. of which Humphry owned the first impression.) Romney and Humphry genuinely admired Blake’s work, but their purchases may also have been meant to help him financially.

Of the ten works Blake advertised in 1793, six are designated as “in Illuminated Printing”: America, a Prophecy, Visions of the Daughters of Albion, The Book of Thel, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Songs of Innocence, and Songs of Experience. Of these titles, Romney took copies of America, Visions, and the combined Songs, all of them later copies than those available in 1793. He also purchased two books that had first been created as recently as 1794: Europe and The [First] Book of Urizen. Humphry also took a copy of Europe, copy D, as well as America (H) and Songs (H). He probably owned these before he commissioned A Large Book of Designs (A) and A Small Book of Designs (A) no later than 1796, the year inscribed on an impression from Urizen in copy B of the Small Book, which, as Viscomi points out, was probably produced in the same printing session as copy A.It is likely that Humphry owned the illuminated books before commissioning the two books of designs, since duplication of plates he already owned was avoided. See Bentley, BB p. 356n1 and Viscomi, “The Myth of Commissioned Illuminated Books” 62. The fact that Romney’s and Humphry’s choices overlapped in at least three instances (America, Songs of Experience, and Europe) suggests that there was no prior agreement as to which works would be bought by each, and, as will be seen, their tastes were very different as far as Blake’s productions were concerned.

One further question concerning Humphry must be answered. Why would a man who was going blind buy and even commission works of art? It is true that more than a decade later, after his sight is supposed to have failed entirely, Humphry caused Blake to write a detailed account of the version of the Last Judgment commissioned by the Countess of Egremont. This was an act of friendship—the picture, Blake wrote to Humphry, “but for you might have slept till the Last Judgment.”Written in 1808 at the end of Blake’s description (E 554). Humphry also owned a copy, annotated by Blake, of the leaflet advertising Blake’s exhibition of 1809. See Essick, The Works of William Blake in the Huntington Collections: A Complete Catalogue (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, Art Collections, Botanical Gardens, 1985) 179-80. However, in 1796, when he praised Blake’s designs to Farington,His admiration was expressed in a conversation noted by Farington on 19 February 1796: “West, Cosway & Humphry spoke warmly in favour of the designs of Blake the Engraver, as works of extraordinary genius & imagination. Smirke differed in opinion, from what He had seen, so do I” (Farington, Diary 2: 497). Humphry was still sufficiently sighted both to enjoy and to make art. He had exhibited nine works at the Royal Academy exhibition the previous year,See Graves, The Royal Academy of Arts: A Complete Dictionary of Contributors and Their Work from Its Foundation in 1769 to 1904, 8 vols. (London: H. Graves, 1905–06) 4: 194. one of them the striking pastel portrait Baron Nagell’s Running Footman (Tate Britain), and he may have thought his eye problem was in remission.Professor Kenneth Polse of the School of Optometry, University of California, Berkeley, suggests (e-mail communication) that optical damage from a riding accident was likely to be to the cerebral cortex rather than to the eyes themselves. In Humphry’s time, such brain damage would have been far beyond the capacity of surgery to cure or ameliorate. Unfortunately, his crayon portraits of the Prince and Princess of Orange, shown at the Royal Academy in 1797,See George C. Williamson, Life and Works of Ozias Humphry, R.A. (London: John Lane, 1918) 5. were among the last pictures he exhibited.

In order to make their purchases, Blake’s clients had to visit him, as the works were, in the words of “To the Public,” “on Sale at Mr. Blake’s, No. 13, Hercules Buildings, Lambeth” (E 692). If, as Viscomi argues, Humphry bought his three illuminated books on different occasions,Viscomi, “Blake’s Printed Paintings.” he may have visited Blake five times, as he also ordered the plates that he wanted Blake to color print without texts. He would then have returned to pay Blake for them, and to take them away. Romney, in order to commission his watercolored copy of Urizen, must first have seen a color-printed one at Blake’s, as all the other copies of this period are color printed. All this suggests more customer traffic at Hercules Buildings in the mid-1790s than is sometimes supposed.

❧

What were the interests of Romney and of Humphry as collectors? Although they obviously shared considerable common ground in desiring to own Blake’s works, in some respects their preferences were very different. The nature of their entire collections is an indication of this. Romney’s collection was sold in a series of auctions that took place from a year before his death to 1894.For dates and locales of sales and titles of catalogues, see Frits Lugt, Répertoire des catalogues de ventes publiques (Leiden: IDC Publishers, 2004–) <http://lugt.idcpublishers.info>. Sold first, at Christie’s on 18 May 1801, were his casts of antique sculpture.A Catalogue of the Capital Collection of Casts from the Antique: Among Which Are the Apollo of Belvidere; Castor and Pollux, and the Laocoon; a Very Fine Skeleton; Various Basso Relievos, Busts, and Fragments, Being the Entire Collection of That Celebrated Artist, George Romney, Esq. At His Late Residence, Holybush Hill, Hampstead. Romney had accumulated these, largely with the help of Flaxman, for the benefit of the art students who would come to his house in Hampstead to sketch, just as he himself had sketched in the Duke of Richmond’s cast gallery early in his career. Romney’s paintings, drawings, and prints were sold at six subsequent sales. The Philipe sale of 22-23 May 1805 (Lugt 6955), comprising 228 prints, 13 books of prints, and 24 portfolios, was entirely devoted to the graphic art. There were drawings ascribed to Giulio Romano, Rembrandt, Rubens, and Parmigianino, and prints by Marcantonio Raimondi (over 100), Rembrandt (116), Dürer (27 “wooden prints” and 16 engravings), Piranesi, Bonasone, Aldegrever, Mantegna, Earlom, and John Hamilton Mortimer. The Christie’s sale of 27 April 1807 (Lugt 7230) included some oil sketches Romney had made after Raphael, Titian, Barocci, and other masters, “A Pietà by Caravaggio, original and fine” (bought by the dealer Michael Bryan for £6.16.6), and some of Romney’s own paintings. A number of unsold items were again offered at Christie’s on 29 June 1810 (Lugt 7823). Romney’s Mrs. [Perdita] Robinson (Wallace Collection) was then bought by the Marquess of Hertford for 20 guineas,See Alex Kidson, George Romney: A Complete Catalogue of His Paintings, 3 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015) 2: 495. and Newton and the Prism by William Chamberlayne, an ancestor of Romney’s future biographer, for £31.10.See Kidson, George Romney: A Complete Catalogue of His Paintings 3: 822. For the price, see the Getty Provenance Index. The reference is to Arthur B. Chamberlain (see note 24). (It is reportedly still in the possession of the Chamberlayne family.) The Philipe sale of 22-23 May 1825 (Lugt 10898) was, like the 1805 one, principally of prints—240 of them—plus 6 drawings and 24 “various.” The sale of the collection of John Romney, the artist’s son, in May 1834 featured important paintings that had been bought in at previous auctions, some of which were again bought in at this one. What is most important to us about this sale, however, is that, as Viscomi discovered, it included some of Blake’s illuminated books. Last, at the Elizabeth Romney sale (Lugt 52642) at Christie’s on 24-25 May 1894, 57 paintings were listed, 26 drawings, 65 prints, 4 miniatures, some autographs, 46 books, and 8 “various”—a total of 207 items.

As we can see, as a collector Romney was primarily interested in prints. Most of the paintings and drawings he owned were by himself, either sketches made for his own use or paintings that for one reason or another had not been sold, not been paid for, or not delivered. In contrast, his print holdings were both extensive and diverse. Unfortunately, the catalogues are uninformative about individual prints, but it is striking that, in addition to mainstream printmakers like Marcantonio Raimondi and Rembrandt, Romney shared with Blake an interest in less avidly collected engravers like Bonasone, Dürer, Aldegrever, and Mantegna. In the first prospectus for his “Canterbury Pilgrims” engraving, Blake aligned himself with “Albert Durer, Lucas, Hisben [Hans Sebald Beham], Aldegrave and the old original Engravers, who were great Masters in Painting and Designing” (E 567). Blake also showed a friend George Cumberland’s book on Bonasone in 1800,Letter to Cumberland, 1 September 1800 (see BR[2] 96). Cumberland’s Some Anecdotes of the Life of Julio Bonasoni, a Bolognese Artist was published by G. G. J. and J. Robinson in 1793. and, although he does not mention Mantegna, it has been authoritatively stated that “Blake takes us very close, indeed, to an understanding of the hard, lapidary, intellectually complex and high-minded, demanding world of Mantegna and his insistence on the ‘wirey line of rectitude.’”Keith Christiansen, The Genius of Andrea Mantegna (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009) 46. The quotation is from Blake’s Descriptive Catalogue, E 550.

As far as affinity with Blake as an artist is concerned, Romney, at times a linearist himself (as in his great drawings at Liverpool),See Kidson, George Romney 1734–1802 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002) 118-37. was clearly interested in Blake’s “hard and wirey line of rectitude and certainty.” The back-and-forth aspect of the two artists’ work was noted as early as 1906: An India-ink drawing … entitled “Har and Heva bathing: Mnetha looking on” (one of a set of twelve illustrations to his own poem “Tiriel”), is a good example of the Romney influence, which is clearly distinguishable in the curves of the figures, in the breadth of the light effects, and in the character of the forest background; and from the designs of the latter from “Shakespeare” and “Milton” it is sufficiently clear that the gain was not on Blake’s side alone.Archibald G. B. Russell, ed., The Letters of William Blake Together with a Life by Frederick Tatham (London: Methuen, 1906) xxii-xxiii. Subsequent scholarship has made us all the more aware of affinities between Blake and Romney. Arguing from strong circumstantial evidence, Jean H. Hagstrum asserts that in the late 1780s and early 1790s Blake knew Romney’s drawings, and that “a linear and thematic stamp from Romney is visible on Blake’s works from the early Tiriel to the very late Dante illustrations.”Jean H. Hagstrum, “Romney and Blake: Gifts of Grace and Terror,” Blake in His Time, ed. Essick and Donald Pearce (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978) 208-09 [quotation from 208]. Considering Romney as both a collector and an artist, it is not surprising that he responded so positively to Blake.

Humphry was a different kind of collector, if, indeed, he can be called a collector at all. His works of art, some of which were sold at Christie’s on 29 June 1810, fall into several groups.Lugt 7823. Humphry’s son, William Upcott, made a manuscript catalogue of his father’s pictures (British Library Add MS 49682). The contents of these sources are not identical, partly because Upcott kept some items, such as the Blakes. Some are oil copies that he did in Italy of paintings by, among others, Michelangelo, Raphael, Titian, and Rubens. There are also some oil copies after British artists, including Reynolds and Samuel Collins (the Bath miniaturist who taught Humphry). His original paintings by other artists include View of Dover Castle by his friend William Hodges; Diana and Callisto attributed to Domenichino; a portrait of Anna Sophia Herbert, Countess of Carnarvon, attributed to Anthony van Dyck; a head of Christ attributed to Fra Bartolomeo; what is characterized as “a repetition picture” of Pope Paul III by Titian; and a striking oil portrait of Humphry himself (Wadsworth Atheneum) painted in 1784 by Gilbert Stuart. (He also acquired James Barry’s Chiron and Achilles by 1808, but here he appears to have acted as a middleman for David Steuart Erskine, Earl of Buchan, who owned it by 1809.)See Williamson, Life and Works of Ozias Humphry 203-04. This painting, now entitled The Education of Achilles, is at the Yale Center for British Art. Among his own paintings appear the ambitious double portrait The Ladies Waldegrave (which was to become the object of a lawsuit after its sale as by Romney in the early twentieth century) and Portrait of Lady Affleck, Wife of Admiral Affleck, Habited as a Greek. Humphry’s “Crayon Portraits, not framed” include Warren Hastings, William Pitt, and two of Benjamin West. Among the subjects of “crayon portraits, framed and glazed” are Samuel Johnson, the Prince of Orange, and the Princess of Orange. Baron Nagell’s Running Footman was kept by Upcott and auctioned in 1846. Among miniatures are portraits of Charles Stuart, the Pretender (done in Italy), Richard Brinsley Sheridan, and Hastings. The reason for Humphry’s owning some portraits that he had painted may be that he wanted to keep versions of images already sold, or that he produced more copies of a portrait than could be sold.There are, for example, at least two examples of the Stuart portrait in private collections. See <http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/explore/by-publication/kerslake/early-georgian-portraits-catalogue-charles.php>. Also, some portraits were never paid for, such as those of the Prince and Princess of Orange, and therefore never delivered. Humphry also owned ninety or so engravings, many of them after his own portraits, and some after others.

However, it should be mentioned that our two sources of information are not complete. For example, Humphry’s engraving by Johann Gottfried Haid after Nathaniel Dance, “The Death of Virginia” (British Museum 1873,0809.235), published by Henry Parker in 1767, is to be found neither in the 1810 sale catalogue nor in Upcott’s manuscript list. The same may be said of his Blake holdings, none of which, including the very rare Moore & Co. engraving (British Museum 1868,0711.439), appears in either source, although we know that Upcott retained his father’s illuminated books and also owned “Four Drawings, by Blake.”Upcott sale, no. 91, sold for five shillings (Evans, 25 June 1846). The drawings have yet to be identified and located. Humphry also owned Hodges’s Select Views in India (1786–87), comprising forty-eight aquatints, given him by the artist. It is possible that Humphry’s print collection was more extensive than previously thought. For the most part, however, the art owned by him was, unlike Romney’s, largely connected with his own career and professional interests.

❧

With this background in mind, we may consider the choices that the two artists made from among Blake’s works. Romney’s America (A) (Morgan Library) is relief etched and hand colored, with white-line etching on some plates, as is its companion, Europe (A) (Yale Center for British Art). His Visions (F) (Morgan Library) is relief etched and color printed with hand coloring, with white-line etching on one plate, while Songs (A) (British Museum) is relief and white-line etched, with hand coloring. His magnificent Urizen (B) (Morgan Library) is so intensely watercolored that its medium has been mistaken for color printing. It is not their media that distinguish these works as a group, but their superlative quality. His copies of America, Songs, Europe, and Urizen belonged to a deluxe large-paper, recto-only edition of all Blake’s illuminated books through 1794. Visions (F) was not part of the deluxe set, although printed recto only on relatively large paper. It may be that someone else bought the deluxe Visions (G) before Romney had the opportunity to do so.

Copy A of the Songs, partly because of the beauty and subtlety of its coloring and partly because of the quality and size of its paper, is one of the most splendid. It comprises fifty leaves. Compared to the size of the images, which typically measure 11 x 7 cm., the paper size is enormous, 38 x 27.1 cm.For this copy the leaf size is from Bentley, BB p. 367, verified by my own measurements. (Although Bentley gives width first, I give height first, as is the norm.) The image size is my own measurement. One might think that Blake’s relatively small prints would appear lost on the folio-sized leaves, but actually the opposite is true. The surrounding white space acts as a foil to the gemlike designs, seeming to funnel the eye into them. The coloring, applied by hand to the relief-etched print, is remarkably subtle, perhaps most so in its blues and greens. Sometimes this involves an independent effect, like the strikingly blue-clad angel in the right margin of “The Little Boy Found” or the greenery that entirely surrounds the text in the first plate of “A Cradle Song” and extends horizontally into it to divide the stanzas. More often it is a matter of combinations. In the “Introduction” to Innocence, for example, all the figures in the panels formed by the bright-green vines are seen against pale-blue backgrounds. Green dominates the top half of the first plate of “The Ecchoing Green,” with its luxuriant leafage above and light-blue background, on which float green tendrils, below. Jesus in the second plate of “The Little Black Boy” sits under a blue sky with his feet on the green earth and a tree’s green leaves bending over him. Rich greenery fills the right side of the second plate of “Night,” almost touching the shrubs that stand in the background against a pale-blue sky; of the five figures walking on the greensward, two are clad in a darker blue. This is not to say that equally beautiful color combinations do not occur in other copies of the Songs; rather, in copy A the blues and greens of Innocence cumulatively create a mellifluous, cool effect that evidently appealed to Romney’s painterly eye.

We would not expect to encounter such harmony in Experience. There is a remarkable range of colors in the designs, from the palely tinted garments of the title page to the sky, part bright yellow, part deep blue, of “The Fly.” In the frontispiece deep-blue hills stand against a rich yellow-to-reddish sky. Similarly colored hills and skies appear in “Holy Thursday” and “A Poison Tree,” the dead body in each belying the beauty of these backgrounds. Yellow turns up in unexpected places, such as the clouds on which the text of the “Introduction” is written and the skies of “The Angel.” Only “The Chimney Sweeper” image mirrors its text: the black cloud matches the color of the boy’s clothing and bag of equipment, the surrounding snow his white face.

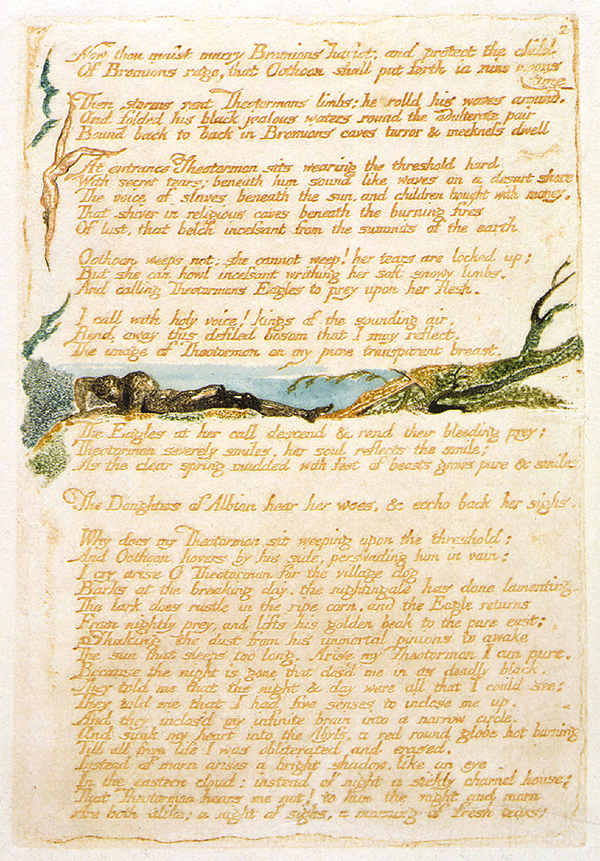

Romney’s copy (F) of Visions of the Daughters of Albion was one of fifteen or sixteenCopy Q is known only from a sales catalogue listing of 1897 (BB p. 477). produced by Blake from 1793 to 1796. Unfortunately, very little is known about the dates at which the others were originally sold or who bought them, other than that Blake’s close friend Cumberland obtained copy B (British Museum), presumably early on. H. I. Reveley acquired copy C (Glasgow University Library) at an unknown date but probably early as well,See BB p. 473. Bentley plausibly conjectures that H. I. Reveley may have been a relative of Willey Reveley, with whom Blake corresponded in October 1791 and who commissioned Blake to engrave plates after drawings by William Pars for volume 3 of The Antiquities of Athens (see E 699). If that is so, H. I. Reveley is likely to have been an early purchaser. and the bibliophile Thomas Dibdin owned copy G (Houghton Library, Harvard University) by 1816. Visions (F) is the only illuminated book owned by Romney that was not part of the deluxe set. It is nevertheless printed on very large paper, all but one leaf measuring 38.2 x 27 cm., and with generous margins (bottom 12.27 cm., top 7.78 cm., left side 8 cm., right side 7.3 cm.). The leaves are printed on one side only, as in deluxe copy G, but not in copies A-E or H-M.See BB pp. 466-67, according to which the only copies in addition to F and G that were printed on only one side are N, O, P (all c. 1818, printed on paper watermarked 1815), and Q. The coloring is extraordinarily dramatic—only in copy G does the intensity of coloring even approach that of F. The frontispiece is very dark, so dark that the orb seen in a break in the clouds might be the moon rather than the sun, were it not for a ruddy glow around it. In contrast, some areas of the title page are very bright, with deep-red color printing suggesting a fiery heart behind the fleeing figure of Oothoon, and a wash of rainbow-like colors going diagonally across most of the design. However, the background, exposed to the right and lower left, is inky black. Plate 3,For the illuminated books, I use Bentley numbers. Where there are etched or penned Blake numbers, I give Blake numbers with Bentley numbers in brackets (if the Blake and Bentley numerals are the same, only one is given). “The Argument,” has vivid bands of primary color—yellow, red, violet, and blue—streaming from the ground with the reticulated, grainy texture imparted by color printing. Of special interest in this regard are plates in which the beauty of the color printing and watercolor sharply contrasts with the agony of the scenes: the golden ground on which naked victims lie at the bottom of plate 4 and the horizontal band showing a dying slave near the middle of plate 2 [5] (illus. 2).

The William Blake Archive describes Romney’s America (A) as “relief etching, with hand coloring and extensive white-line etching on plates 1, 8, 10, 11, and 15,” adding that “most other plates bear at least touches of white-line etching/engraving.” Its colored state puts it in the minority of the copies of America (the other known colored copies are K, M, and O).See D. W. Dörrbecker, ed., William Blake: The Continental Prophecies (Princeton: Princeton University Press/William Blake Trust/Tate Gallery, 1995) 77. The tally here does not include copy R. Robert N. Essick informs me (e-mail communication) that copy R, sold at Christie’s New York on 13 Nov. 1987, lot 46, is uncolored. Blake liked copy A enough to use it as a model (or to have Catherine Blake so use it) for the hand coloring of copy K (Beinecke Library, Yale University). It may be that Romney first saw copy A uncolored and asked Blake to color it as a companion for his Europe, or simply because he preferred color to monochrome, or both. The colors are at times very striking indeed. In the frontispiece, the wings, hair, and legs of the chained giant figure are yellow, as are the woman’s hair and left thigh and parts of the damaged structure to our right. This may be meant as an effect of the setting sun (imagined as behind the viewer), which also touches the black clouds, giving them rosy outlines against the black sky. Yellow appears again in the reading female and child of the next plate, but the dominant color here is blue—the color of the reading male, of the lower part of the cloud on which both he and the female sit, and of the dress of the woman who is vainly trying to revive a supine man with the kiss of life. In the first page of text, intense blues and greens are the predominant colors. A naked man and woman stand against the sky on a green hummock, displaying gestures of grief and horror at the sight of a boy chained on the ground (these are or will become Los, Enitharmon, and Orc, whose narrative is not given here but in Night the Fifth of The Four Zoas). Next, against a sky washed blue the unchained boy pushes himself out of the ground, his flesh color contrasting with the gray earth around him. Facing a yellow sun, he rises next to a grape vine with two enormous green leaves. The pink and blue sky remains in plate 3 [5], with a male figure, trailing chains, floating upward. Enormous reddish flames emerge at the center from a huge trumpet blown by another male figure, while at the lower left a man, a woman, and a child run on the green earth, against a bright-yellow background, from the red flames behind them. The three refugees reappear at the lower right of plate 4 [6] beneath blue clouds tinged with green and rose. In the foreground is a bright-green hummock that in some other colored copies, O, for example, is gray, differentiated in color from the ground and appearing to be a sea creature (an orca?) with two pairs of flippers and no visible head. White is used both for the child and for the bearded old man (Urizen?)Erdman identifies the falling figure as George III and suggests that the design relates to the text of cancelled plate b. See The Illuminated Blake (1974; New York: Dover, 1992) 142. diving down the left margin, pursued by a green, winged dragon-serpent with human hands.

Two blues color the sky of plate 5 [7], one a bright azure, the other tinged with gray shading downward to almost black. The figures are defined especially sharply in black ink. In plate 6 [8] the newly resurrected man sits on a bright-green hummock and the green earth again appears, with a green-leaved knapweed, at the bottom of the plate. (Erdman suggests that the knapweed is “harmless,”See Erdman, The Illuminated Blake 144. but in fact it is an aggressive invader of environments, and some species are poisonous. As ever, Blake is conscious of the two faces of the natural world.) A striking example of how design can relate to text is plate 7 [9], where the Herod-like fulminations of Albions Angel are contrasted with an Edenic scene in which birds of paradise sit on a birch tree and two naked children sleep on the green earth beside a sleeping ram. The sky is awash with colors—from left to right violet, blue, yellow (becoming very intense above the sleepers), pale blue, and a darker blue.

Greenish-yellow blue, forming the cloud mass against which the text appears, is almost the only coloring in plate 8 [10], except for the heightening of Urizen’s paleness with white on his right knee, arms, and the lower edge of his garment, associating him with the white crests of the waves below. The white-line etching that forms the basis of the cloud masses in most copies becomes secondary here. Yellowish wheat bends over a child whose rigidity suggests death in plate 9 [11]. Green-leaved flowers among the wheat have been variously identified, but the fact that they are there at all, symbols of hope, is what is important. They are much more noticeable in color.

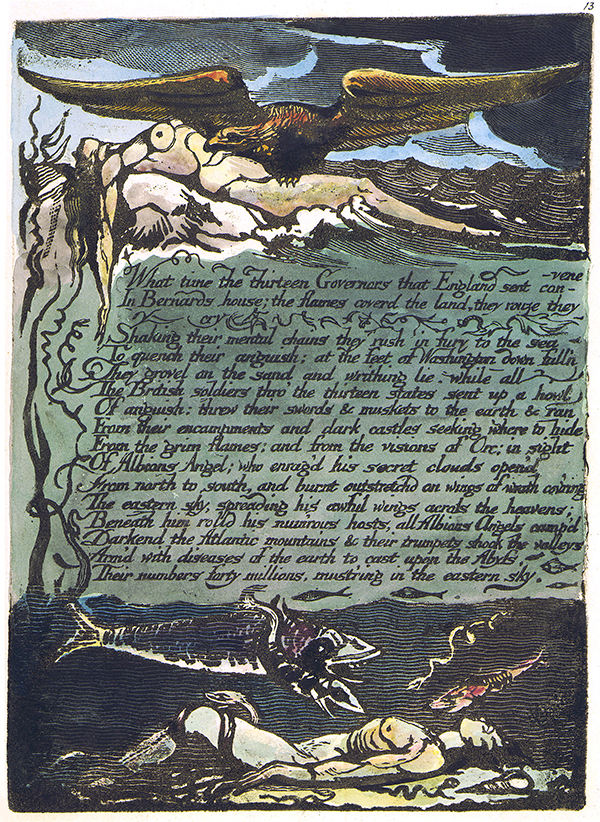

The naked figure of Orc in plate 10 [12] is entirely surrounded by flames, which he seems to be orchestrating with his outstretched arms. A reddish flame that crosses his upper body has been, as the Blake Archive editors point out, added in watercolor. It connects with a flame, barely noticeable in the monochrome copies, licking up over the figure’s left shoulder. The fire that fills much of the plate is red, black, and yellow, the text appears in a violet-to-rose background, and the youth’s curly hair is touched with yellow. Whether intentionally or not, the coloring gives the conflagration a massive solidity. The main difference that color makes in plate 11 [13] is the beautifully variegated deep blue and yellow of the serpent at the bottom. The child riders are flesh colored. As Richard Thomson recognized, the bent-over, bearded patriarch with a stick, seen entering an archaic-looking, mausoleum-like structure in plate 12 [14], is “another instance of Mr. Blake’s favourite figure of the old man entering at Death’s door.”Smith, Nollekens and His Times 2: 477. Thomson previously commented on the image of the old man in “London” as “a favourite one with him [Blake],” and his use of the expression “Death’s door” suggests he had seen Luigi Schiavonetti’s engraving “Death’s Door” after Blake in either the 1808 or the 1813 edition of The Grave by Robert Blair. On Thomson, see par. 33. The nude figures at the top and bottom of plate 13 [15] (illus. 3) are colored greenish gray, and the whole text washed blue green. The eagle perched on the upper, female body is tinged with bright yellow. Blake’s use of white line for both the surface and the depths of the ocean is very striking. Thomson singled this plate out as “a very fine specimen” of Blake’s success in depicting water.Smith, Nollekens and His Times 2: 477.

In plate 14 [16] the background of the text is blue, as are the clouds that form the background of the central image. The worshipful youth’s garment is green, and a patch of greensward lies beneath him. His expression is not as fearful as it is in copy H and other uncolored copies. Flames colored similarly to those in plate 10 [12] fill the lower margin of plate 15 [17], with flesh color, and in one instance green, added to the naked women who “feel the nerves of youth renew, and desires of ancient times” (line 25). The grape leaf at our left is bright green, but the dark bunch of grapes below it is partially obscured by black flame. In 16 [18], the final plate, some blue is added to the white beard of the kneeling giant to make clear that it turns into a waterfall.

On the whole, the coloring of America (A) is not entirely successful. America was conceived as a monochromatic work, the form in which Humphry purchased it. Dörrbecker remarks that “the extensive use of white-line modelling for added structuring of the relief-etched plateaus of the plates [is] a technique which creates marked graphic contrasts that are strongest when left uncoloured.”Dörrbecker 77. This white-line work is sometimes partly, though not entirely, obscured by coloring. (Europe [A] also suffers from this problem: in both, hand coloring tends to obscure the tonal hatching.)

Romney may have owned copy A of Europe. The darkness and heavy coloring of a number of its plates have suggested to some that the coloring of this copy may have been done, at least in part, by a hand other than William Blake’s.See David Bindman, William Blake: His Art and Times (New York: Thames & Hudson, 1982) 106. The opaque red and black paint of plate 1 produces a murky effect, some plates have thicker outlines than those of other copies of the mid-1790s, and some are colored more darkly and more heavily. The editors of the Blake Archive, however, attribute these effects to Blake’s own attempt to imitate color printing.See <http://www.blakearchive.org/new-window/note/europe.a?descId=europe.a.illbk.01>. Romney may have chosen copy A because it was part of the deluxe set of 1794–95, of which he owned at least three other examples, the Songs, America, and Urizen.

In addition to the frontispiece, full-page designs 6 [9] and 11 [10] are powerful visual statements of themes that occupied Blake in works both before and after Europe, like A Breach in a City, the Morning after the Battle (c. 1795–1800, Ackland Art Museum, UNC Chapel Hill)Martin Butlin, The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake, 2 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981) #191. This book will be cited as Butlin, followed by catalogue number. and Pestilence (c. 1790–95, ex-Gregory Bateson, Butlin #190). Plate 6 [9] shows two women (perhaps a servant and her employer), one of whom is hunched over in despair and the other, who wears a pearl choker, is looking anxiously upward. Before them is a naked, supine child, stiff in death like the ones in America plate 9 [11] and in “Holy Thursday” of Experience. Behind is a huge, arched fireplace, heated by red flames and issuing black smoke, with an enormous cauldron in it. (Massive structures seldom portend good in Blake’s art.) Near the top center of this page in Humphry’s copy D, someone wrote, “preparing to dress the Child.”The pen-and-ink annotations in Europe (D) are attributed to George Cumberland, but according to Dörrbecker (209), this note, in pencil, is in another hand. Jonathan Swift had made the devouring of children the vehicle of his satire in A Modest Proposal (1729); here Blake renders the subject visually as a metaphor of his own contemporary England. Plate 11 [10] alludes to the Great Plague of 1665 but also to the sickly state of Britain in the mid-1790s. A grim-faced bellman walks along a brick wall in front of which one woman is gesticulating in despair, while another lies dying in a man’s arms. Unlike most copies of Europe, copy A does not have a shadow slanting through the design and darkening its entire upper-right area. This shadow was added to the print in watercolor, and so could have been left out in coloring.

Europe is rich in large designs in addition to the full-page ones. Romney might have found one of these of particular interest.

The greatest glory of Romney’s Blake collection is The [First] Book of Urizen. At first sight, it appears to be color printed (as are six of the eight extant copies of Urizen), and it was once taken as such. However, as Viscomi was the first to show, the medium is actually watercolor and pen and ink, displaying some of the intensity and apparent texture of color printing.Viscomi, “The Myth of Commissioned Illuminated Books” 50. It is possible that this copy was custom made for Romney. Perhaps he saw other copiesCopies D (British Museum) and J (Albertina) have 1794 watermarks. See Bentley, BB p. 168 and Blake Books Supplement (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995) p. 72. at Hercules Buildings and commissioned a copy to his own specifications. While it is true that Blake’s attitude toward his illuminated books of this period was “print it, and they will come,” Urizen (B), part of the large-paper set produced in 1794–95, may be the rule-proving exception.

The ordering of leaves in Urizen varies, and scholars have made efforts to interpret the significance of these variations.See, for example, Robert E. Simmons, “Urizen: The Symmetry of Fear,” Blake’s Visionary Forms Dramatic, ed. David V. Erdman and John E. Grant (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1970) 146-73. Blake himself numbered the pages of copy B.See BB p. 168, column headed “Blake numbers.” Two other copies, D (British Museum) and G (Rosenwald Collection, Library of Congress) have Blake numbers; neither of these has all twenty-eight plates. I will give a brief, literal description of those designs that are especially striking and/or those that display interesting differences between copy B and five copies that Blake produced in 1794: A (Yale Center for British Art), C (Yale Center for British Art), D (British Museum), F (Houghton Library, Harvard University), and J (Albertina Museum, Vienna).I have not seen copy E (private collection).

Plate 1: The title is The First Book of Urizen (by 1818, during which he produced copy G, Blake knew there would be no Second). The image below shows a white-bearded, white-haired old man, seated against rocks that suggest the Tables of the Law. His eyes are closed, and he is writing with both hands. His tools, indistinct in some copies, are in this impression clearly a quill pen in his left hand and a graver in his right. He uses the big toe of his right foot as a pointer for the illegible text he is transcribing, perhaps an allusion to the Jewish yad, or Torah pointer. Dark tones prevail, except for the whitish appearance of the old man and his book.

Plate 2: The words “PRELUDIUM / TO” and “THE / FIRST BOOK OF / URIZEN” are separated by the graceful image of a woman in a form-revealing gown flying in midair, curving her body and reaching her left arm out to clasp the right hand of a flying infant with prominent dark eyes. The background is gray speckled with white, as if it were color printed, but the effect has been produced by brush and pen. The image and text convey alternative realities, with the latter promising to unfold “dark visions of torment” (line 7).

Plate 3: The top of the first column reads “Chap: I”. An athletic nude man, flesh colored except for his white head, leaps with his back to us through enormous red flames. This page begins the double columns of text, imitating the format of the printed Bible and satirizing it as well.Blake was not alone in producing a double-columned book imitating a book of the Bible. See my “William Blake, Jacob Ilive, and the Book of Jasher,” Blake 30.2 (fall 1996): 51-54.

Plate 4: A man sits on the seaside with thick black rain falling on him and his hands gripping his head in an attitude of despair. This plate, headed “I Urizen: C II”, is found only in copies A, B, and C.For an explanation of why this plate may have been omitted in other copies, see Essick, “Variation, Accident, and Intention in William Blake’s The Book of Urizen,” Studies in Bibliography 39 (1986): 230-35.

Plate 5 [14]: In this full-page design a naked man, white hair streaming, balances his body on two rocks against a black background. This is the first of ten full-page images in Urizen, a feature that must have appealed to Romney, who was principally a print collector, not a book collector.

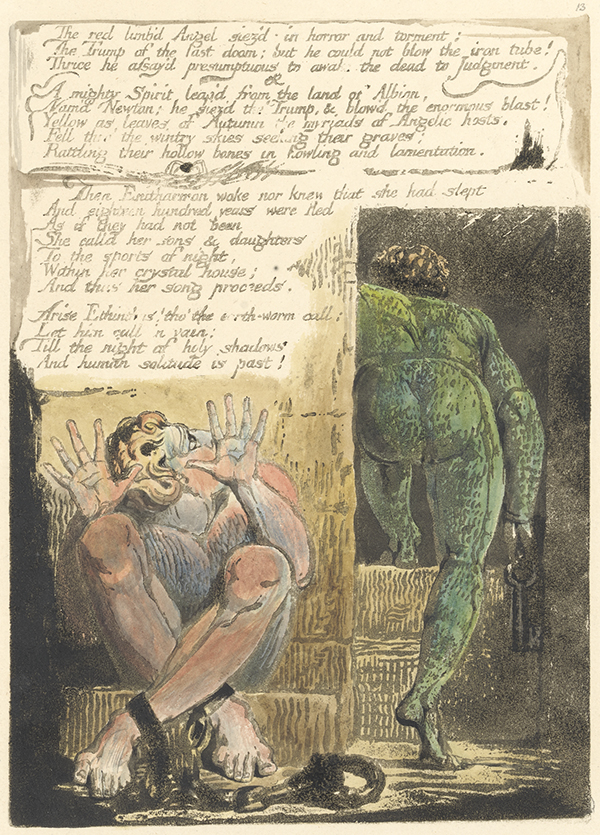

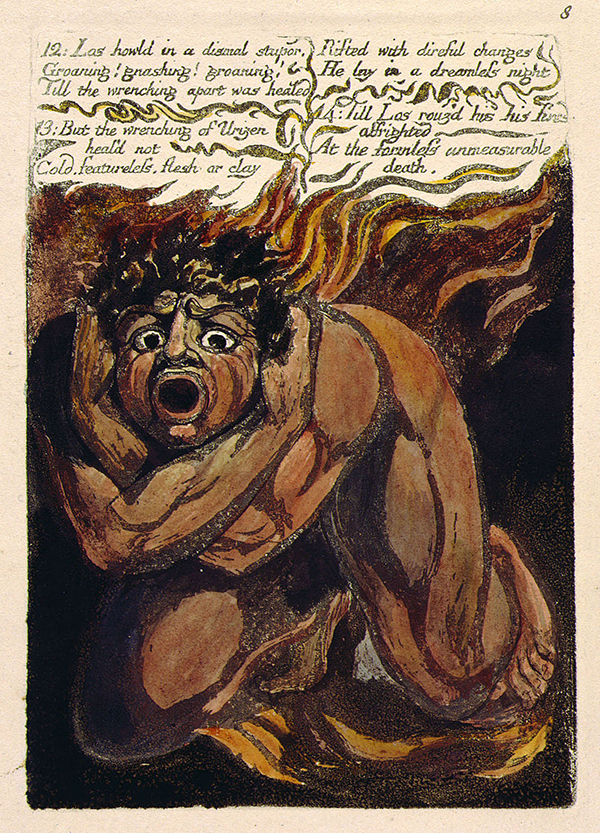

Plate 8 [7]: The fire is red only at its top and black in the rest of the design, while in the other four copies of this period that include this plate it is red almost throughout. A naked male figure is on his knees among flames, his face a grotesque mask of terror (illus. 5). His right foot, only slightly suggested in other copies, has been drawn in, in keeping with Blake’s extensive use of pen and ink in this copy.

Plate 11 [8]: A skeleton, its bones colored greenish brown and black, is hunched in a fetal position against a dark-blue background becoming black toward the bottom. A stroke of light blue, darker in the other copies, goes along part of the toothlike serrations on his back.

Plate 13 [22]: A full-page design shows a naked, white-bearded man sitting with his knees drawn up almost to his shoulders, chained hand and foot, his eyes shut. Yellow to gold rays emanate from his head, but his lips are severely downturned. The heavy chain, curving downward from his right wrist, is visible only in this copy and copy G. The background is mottled, greenish above, dark red below, showing how easily this watercolor could be mistaken for color printing.

Plate 15 [9]: Another full-page design shows a white-bearded and white-haired nude man, eyes closed, with one knee and both hands on the ground. His hair and beard are marked by dark, wavy lines only in this copy. He seems to be supporting a huge, greenish rock of the sort that the young man of 9 [10] is removing. Both this image and the plate “Earth” in For Children: The Gates of Paradise (1793) bear a striking resemblance to a book illustration engraved after Raphael by Blake’s master, James Basire, and published in 1778.Charles Rogers, A Collection of Prints in Imitation of Drawings. See Essick, “Blake in the Marketplace, 2004,” Blake 38.4 (spring 2005), cover and pp. 134-35.

Plate 16 [15]: At the top it reads “1 Urizen C.V:”. A young man leans down from the blue/bluish sky between the heads of two white-bearded men and extends his left arm and hand into the earth. The eyes of the two old men are closed (open in copies A and D). From behind the one at the right a yellow cloak, absent in copies A, C, D, and F, swirls over to the back of the central figure. Yellow flames, reddish toward the center (the rising sun?) run along most of the curve of the globe, and onto it from the youth’s extended hand.

Plate 17 [16]: This full-page design shows a beardless, nude male, hair streaming outward, arms bent behind his head. He is surrounded by flames going from yellow to red to very dark red (almost black). This plate is present only in copies A and B among the copies of this period. Only in this copy do we see tears on the figure’s cheeks.

Plate 18: The heading is “1 Urizen. C:V.” Most of the plate is occupied by a design showing a naked man, with abundant ringlets of hair, in flames. The flames go from yellow and yellow green to dark red to black. His genitals are obscured by a tongue of flame, a curious detail for an artist who had declared “the genitals Beauty.”The Marriage of Heaven and Hell 10.1, E 37. (In copy J the covering flame is omitted, and we see no genitals at all.)

Plate 20 [19]: A male figure kneels in a despairing attitude, hands to lowered head, before a curving female whose face indicates anguish. The background is a very dark red, mottled in imitation of color printing. Only in this copy is the male’s bodysuit red (see BB p. 178).

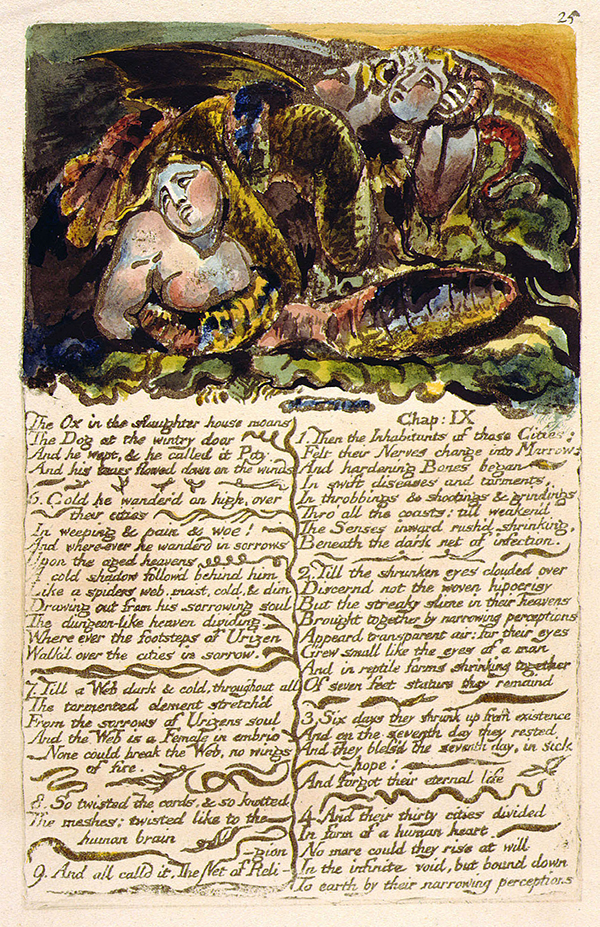

Plate 25: This brightly colored design shows two nude humans, probably female, caught in the toils of a gigantic worm or worms (illus. 6). Only the upper parts of their bodies are shown. A bat-winged creature with a human face is partially visible behind them. Faces and wings vary from copy to copy.For attempts to disentangle the details, see Erdman, Illuminated Blake 207, and David Worrall, ed., William Blake: The Urizen Books (Princeton: Princeton University Press/William Blake Trust/Tate Gallery, 1995) 51-53. Copy B’s is the most brightly colored of the versions.

Plate 26: A full-page design shows a boy wearing a white smock, his hands clasped in front of him and an expression of anxiety on his face as he looks upward. Behind him a large dog raises its head as if howling. The background is a door, the panels of which are less visible in some other copies, divided diagonally into areas of light below and areas of darkness above. The diagonal goes the other way in copies A and F and is not visible in the dark background of copy D or in the almost-as-dark one of copy J. Is the darkness to be thought of as encroaching? Perhaps a solar eclipse is in progress, causing the boy’s fear and the dog’s howling.

The greatness of copy B of Urizen, the only copy Blake is known to have produced by a method other than color printing before c. 1818,In 1818 he printed and hand colored copy G (Rosenwald Collection, Library of Congress). lies not in individual details, important as these may be, but in its overall effect. Its extraordinary richness and variety of color, combined with its firm, detailed outlines, make it one of Blake’s masterworks.

Did Romney read the texts of the illuminated books he bought? He did have an interest in mythological subjects, as evidenced, for example, by his collaboration with Hayley on illustrations for the Cupid and Psyche of Apuleius, and most of the large cartoons now at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool. However, these myths were classical. It is likely that Romney, like most of Blake’s clients, admired Blake’s designs but did not appreciate his texts.An exception was Blake’s friend Benjamin Heath Malkin, who wrote appreciatively of Blake’s poetry, but only of poems in Poetical Sketches and Songs of Innocence and of Experience (A Father’s Memoirs of His Child [London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, 1806] xxvi-xl). Of Blake’s longer poems Malkin wrote, “The unrestrained measure, however, which should warn the poet to restrain himself, has not unfrequently betrayed him into so wild a pursuit of fancy, as to leave harmony unregarded, and to pass the line prescribed by criticism to the career of imagination” (xl-xli). Henry Crabb Robinson, who first introduced German readers to Blake in his article in the Vaterländisches Museum (1811), found only “obscurity” in America and wrote that “Europe is a similar mysterious and incomprehensible rhapsody.”Quoted from the translation in BR(2) 602. Thomson, so appreciative of Blake as an artist, could say even of some of Blake’s most accessible poems, “The poetry of these songs is wild, irregular, and highly mystical, but of no great degree of elegance or excellence, and their prevailing feature is a tone of complaint of the misery of mankind.”Smith, Nollekens and His Times 2: 477. Thomson is speaking of the Songs of Experience. It is unlikely that Romney read his illuminated books, other than perhaps the Songs. The same is probably true of Humphry, especially as thirty-one plates of his purchase from Blake were prints, mostly from illuminated books, without their texts.

❧

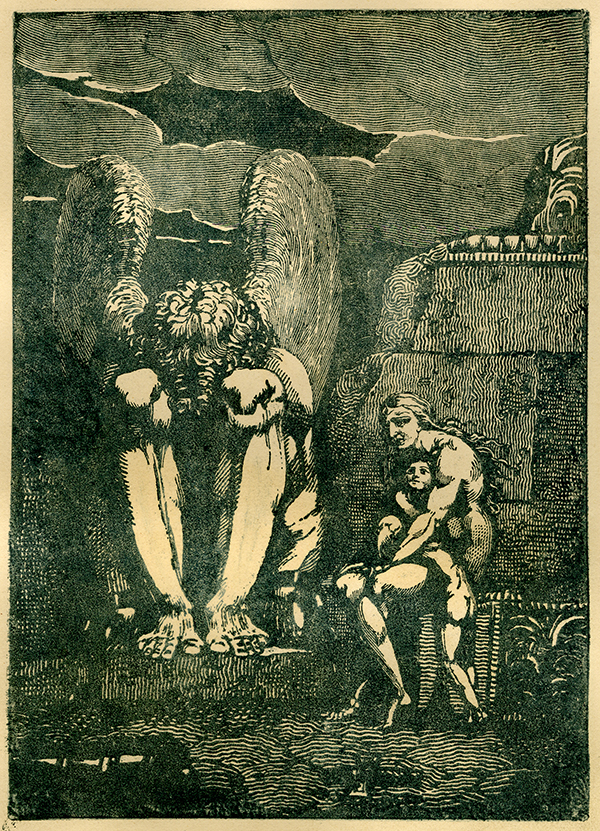

Humphry’s America (H) (British Museum), the only uncolored work that either artist acquired, has the special beauties of Blake’s monochrome printing at its best. It has the full eighteen plates, printed recto/verso except for the frontispiece and the title page. As in the majority of copies (but not Romney’s copy A), four lines of plate 4, which may be taken to express Blake’s loss of faith in the American Revolution, were masked. Its leaves (which may have been cut down) measure 37.4 x 24.6 cm., with comparatively little margin.The margins of paper around the printed plate are: bottom 7.30 cm., top 6.67 cm., left side 4.13 cm., right side 3.49 cm. For the title page the right- and left-side margin measurements are 1.90 cm. and 4.13 cm. One of its most striking features is, as in the other uncolored copies, the prominence of white-line etching, as in the wings of the giant figure of the frontispiece and the sky behind him (illus. 7).

Because of Humphry’s eye problem, he preferred brightly colored images to texts that he would have had difficulty in reading. He probably chose Europe because of the relative quantity as well as the quality of its visual content. Of its seventeen plates,A complete copy has eighteen plates, but plate 3 is missing from all but two. four (counting the title page) are full-page designs. Some other designs, among Blake’s most memorable, occupy half or more of the space of ten more pages. There were probably several copies to choose among. Of the eight that Blake printed in 1794 and 1795, the original buyer of only one, George Cumberland’s copy C (Houghton Library, Harvard University) is certain. (A) was in the collection of Isaac D’Israeli by 1835, but is thought to have previously belonged to Romney (see above). The owner of copy B (Glasgow University Library), perhaps by 1821, was Thomas Griffiths Wainewright, but he may not have been the original buyer. The first owners of (E) (Rosenwald Collection, Library of Congress), (F) (Berg Collection, New York Public Library), (G) (Morgan Library), and uncolored (H) (Houghton Library) are unknown. Thus Blake may have had several copies of Europe on hand when Humphry visited him. (D) (British Museum) is brightly colored by a combination of color printing and watercolor on ten large (36.3 x 25.5 cm.) leaves printed recto/verso.

Humphry’s Europe was studied by more than one of Blake’s contemporaries. As mentioned, on some of its pages there are pen-and-ink inscriptions, attributed to Cumberland, taken from Edward Bysshe’s Art of English Poetry.There are also some inscriptions in pencil by another hand (see note 65). (Although Blake owned a copy of Bysshe and copied two texts from it into his Notebook in 1807,See E 696. On this subject, see S. Foster Damon, William Blake: His Philosophy and Symbols (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1924) 347-51. there is no way of knowing whether he had anything to do with choosing the quotations.) In 1810, shortly after his father’s death, Upcott probably showed this copy, with other Blake material from his father’s collection, to Robinson, who wrote down some passages for reference.See BR(2) 297. Upcott also showed his Blakes to John Thomas Smith, and Smith in turn showed them to Thomson, who wrote comments about them.See Smith, Nollekens and His Times 2: 454-88. Thomson’s remarks are on 475-80. Curiously, Thomson (writing of Experience) says that “the whole of these plates are coloured in imitation of fresco” (2: 477) although, as one of our sources of what Blake meant by “fresco,” Smith himself should have known that they were not. See my “William Blake’s ‘Portable Fresco,’” European Romantic Review 24.3 (2013): 271-77. Thomson, who was to be joint author, with Upcott and E. W. Brayley, of the London Institution’s library catalogue,A Catalogue of the Library of the London Institution: Systematically Classed. Preceded by an Historical and Bibliographical Account of the Establishment, 4 vols. (London: C. Skipper and East for the London Institution, 1835–52). may have become involved in Smith’s project through Upcott. Thomson was an expert on medieval illuminated manuscripts, and it is likely for that reason that Smith chose him to write about Blake. (Although Thomson did not publish his books on illumination until much later,For example, A Lecture on Some of the Most Characteristic Features of Illuminated Manuscripts, from the VIII. to the XVIII. Century … to Which Is Added a Second Lecture on the Materials and Practice of Illuminators: with Biographical and Literary Notices Illustrative of the Art of Illumination (London, 1857). he shows his interest in and knowledge of the subject in earlier works.)See An Historical Essay on the Magna Charta of King John (London: John Major and Robert Jennings, 1829) xiii, xiv, and 537. We do not know to whom else Upcott may have shown his Blakes, but these instances should remind us that the reception history of Blake’s illuminated books should not be limited to their owners.

Of plate 1 of Humphry’s copy of Europe Thomson wrote a comment that Blake himself would have relished: The frontispiece is an uncommonly fine specimen of art, and approaches almost to the sublimity of Raffaelle or Michel Angelo. It represents “The Ancient of Days,” in an orb of light surrounded by dark clouds, as referred to in Proverbs viii. 27, stooping down with an enormous pair of compasses to describe the destined orb of the world,* “when he set a compass upon the face of the earth.”Smith, Nollekens and His Times 2: 478. Following this Thomson quotes a passage from Milton’s Paradise Lost, book 7, corresponding to lines 224-31 in modern editions and beginning “in His hand / He took the golden compasses ….” Smith added to this a note on the origin of the image: He [Blake] was inspired with the splendid grandeur of this figure, by the vision which he declared hovered over his head at the top of his staircase; and he has been frequently heard to say, that it made a more powerful impression upon his mind than all he had ever been visited by. This subject was such a favourite with him, that he always bestowed more time and enjoyed greater pleasure when colouring the print, than any thing he ever produced. (2: 478n) Smith’s account, later repeated in Gilchrist’s biography, was presumably given to him by Blake himself. This frontispiece has become what is probably Blake’s best-known image.

Another image in copy D is of special interest. With the exception of his monochrome America, everything Humphry bought from Blake in 1794–96 was color printed. He evidently enjoyed the textured quality of prints such as the title page, with its varicolored coiling serpent, and 9 [12], with its beautiful rococo curves, those of the bending wheat reflected in those of the two flying figures, and in turn by their curling trumpets. Humphry may not have realized the irony of such beauty’s being the agency of disease and death; Cumberland’s inscription, “Mildews blighting ears of Corn,”This and Cumberland’s other inscriptions are to be found at <http://www.blakearchive.org/copy/europe.d?descId=europe.d.illbk.01>, under Supplemental Views. could have enlightened him. Thomson also appreciated the meaning of this image (though not its contemporary relevance), as well as its beauty, describing it as “two angels pouring out the black spotted plague upon England …; in which the fore-shortening of the legs, the grandeur of their positions, and the harmony with which they are adapted to each other and to their curved trumpets, are perfectly admirable.”Smith, Nollekens and His Times 2: 479.

Humphry’s Songs (H) (Maurice Sendak Foundation) is a very early copy of Experience only,At the time of writing, copy H was not available for inspection, and so could be examined in reproduction only, in Gert Schiff, William Blake 22 September–25 November 1990 (Tokyo: National Museum of Western Art, 1990) 80-84 (sixteen of the seventeen plates). numbering only seventeen plates. Printed in 1794 when Experience was still in the process of formation, it lacks eight plates (as did copies F, G, and T1 at the time of printing).See Viscomi, Blake and the Idea of the Book (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993) 269. Four of these, containing “The Little Girl Lost,” “The Little Girl Found,” and “The School Boy,” had been included in Songs of Innocence. The others—“The Sick Rose,” “The Garden of Love,” “The Little Vagabond,” and “Infant Sorrow”—already existed in manuscript drafts but may not yet have been ready for etching and printing. Like the other three early copies of Experience, (H) is color printed. Essick suggests a correlation between the medium and meaning. “The patterns of opaque colors,” he writes of the color-printed copies in general, “match in miniature the ‘fallen light’ and ‘slumberous mass’ of the ‘Introduction’ to Experience, ‘the forests of the night’ in ‘The Tyger,’ the ‘Tangled roots’ in ‘The Voice of the Ancient Bard,’ and the threatening bare roots and branches illustrating ‘Earth’s Answer,’ ‘Holy Thursday,’ ‘The Fly,’ and ‘A Poison Tree.’”Essick, William Blake Printmaker (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980) 149. Schiff remarks on “The Tyger,” “The yellow of the animal’s skin is overlaid by streaks of brown, blue, crimson, and black, as if the tiger had to adapt, by way of mimicry, to the strident colors of a tropical forest.”For enabling me to consult an English typescript of Schiff’s remarks on copy H (pp. 32-35), I am grateful to Robert N. Essick. Even when viewed in reproduction, Blake’s color printing produces some extraordinary effects.

Humphry’s interest was principally in Blake’s images and not his texts, and for that reason he commissioned the prints now called A Small Book of Designs (A) and A Large Book of Designs (A). The leaves for the former measure approximately 26.0 x 18.8 cm. and for the latter 34.5 x 24.5 cm.,Figures from the British Museum website: see <https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=1351975&partId=1&page=1&>, under curator’s comments. no matter what the size of the designs; hence small and large book. The leaves of the Small Book have stitch marks showing that they were once bound together; those of the Large Book do not. Later, Blake seems to have regretted separating the two components of his composite art, writing to the collector Dawson Turner on 9 June 1818: “Those [works] I Printed for Mr Humphry are a selection from the different Books of such as could be Printed without the Writing tho to the Loss of some of the best things For they when Printed perfect accompany Poetical Personifications & Acts without which Poems they never could have been Executed” (E 771). However, the question of whether we regret the existence of these magnificent prints is similar to that of whether Max Brod should have destroyed Franz Kafka’s manuscripts, as Kafka had directed.

In the mid-1790s Humphry was much taken with strong coloring, as in his Baron Nagell’s Running Footman, in which the black skin of the subject contrasts with his sharply red-and-white feathered headpiece, white jabot, and red sleeves.Ruth Kenny of Tate Britain points out that these are the colors of the Dutch flag and that Baron Nagell was the Dutch ambassador to London. See her note at <http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/humphry-baron-nagells-running-footman-t13796>. Smith was struck by “great depth of knowledge in colouring”Smith, Nollekens and His Times 2: 475. in the Large and Small Books and other ex-Humphry Blakes. A British Museum curator remarks that Blake’s “luminous, jewel-like impressions … may have seemed particularly fitting given Humphry’s own artistic productions.”See the link in note 98, above. It may also be, as an expert on miniatures suggests, that during Humphry’s time in India “he was carried away by the glowing colour of the robes worn by the various native officials whose portraits he delighted to paint ….”Williamson, The Miniature Collector: A Guide for the Amateur Collector of Portrait Miniatures (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1921) 147.

As noted, in commissioning these prints, Humphry took care not to duplicate plates from the illuminated books he already owned. Four of the prints in the Large Book exist principally as separate plates,The first-state impression of “The Accusers of Theft Adultery Murder” was bound into Marriage copy B at some point (see par. 43), and the second impression of the first state of “Albion rose” (see par. 5) was added to The Song of Los copy E, but neither of these prints is to be seen in any other copy of an illuminated book. while the rest of the Large Book and the Small Book are from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, The Book of Thel, The [First] Book of Urizen, and Visions of the Daughters of Albion. (Blake took second impressions of these for copy B,See Martin Butlin and Robin Hamlyn, “Tate Britain Reveals Nine New Blakes and Thirteen New Lines of Verse,” Blake 42.2 (fall 2008): 52-72. which is not part of our subject here.)

To what extent would the textless designs of the two books interest viewers unfamiliar with Blake’s myth (a category that would include almost anyone likely to see them)? In the Large Book most, though not all, of the prints establish meaning visually without need of a textual interface. The first, untitled like all the other prints in both series, was called by Gilchrist “a personification of Morning, or Glad Day,”Gilchrist 1: 32. The original order of the prints is unknown. “Albion rose” happens to come first in the British Museum’s arrangement, but in this discussion the prints are arranged for heuristic purposes. probably referring to Shakespeare’s “Night’s candles are burnt out, and jocund day / Stands tiptoe on the misty mountain tops” in Romeo and Juliet (3.5.9-10). “Glad Day” was used in A. G. B. Russell’s pioneering catalogue of Blake’s engravings, and then by Laurence Binyon (then Keeper of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum).Archibald G. B. Russell, The Engravings of William Blake (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1912) 54; Laurence Binyon, The Drawings and Engravings of William Blake (London: Studio, 1922), pl. 34. That title is not to be found in Blake, however. Around 1804 Blake produced an uncolored second state,See Essick, Separate Plates 25. signed “WB inv 1780”,This date, as frequently in Blake, probably indicates the original conception, in this instance pencil drawings of a similar nude male figure made on the recto and verso of a single leaf (Victoria and Albert Museum). Anthony Blunt suggests visual sources in Vincenzo Scamozzi’s L’idea della architettura universale (1615) and in De’ Bronzi di Ercolano; see Essick, Separate Plates 27-28. and gave it the two-line caption “Albion rose from where he labourd at the Mill with Slaves / Giving himself for the Nations he danc’d the dance of Eternal Death.” These lines appear without a title in Erdman’s 1965 edition of The Poetry and Prose of William Blake,Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1965. but in a textual note are given the title “Albion rose.” Both states are now known by this title.See Essick, Separate Plates 24. However, Blake’s distich connects with images of a caterpillar and a bat-winged moth that were added in the second state, and we should not apply the symbolism of that state—or perhaps even the title—to the first. The theme of self-sacrificial redemption does not figure in the earlier version. Instead, we have a celebration of “the human form divine,” with “The head Sublime, the heart Pathos, the genitals Beauty.”See “The Divine Image,” E 13, and The Marriage of Heaven and Hell 10.1, E 37.

Another separate plate appears to be related to America (though not published in that work) because of six lines, beginning “As when a dream of Thiralatha flies the midnight hour,” etched on it in relief but covered by pigment (E 59). (The lines are still partially visible in impression B [National Gallery of Art, Rosenwald Collection], reproduced by Essick in Separate Plates, pl. 5.) These lines would, however, not contribute much to a viewer’s experience of the image, nor would the connection of the plate to America. Thiralatha appears in Europe as one of two “secret dwellers of dreamful caves” (14.26, E 66) and is identified by Damon as “the erotic dream. … Thiralatha is the final stage in Enitharmon’s repression of sex, its reduction to the last, futile effort of the imagination.”Damon, A Blake Dictionary: The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake, rev. ed. (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1988) 402-03. As Damon points out, she also appears as Diralada in The Song of Los, again representing sexual denial: “But in the North, to Odin, Sotha gave a Code of War, / Because of Diralada thinking to reclaim his joy” (3.30-31, E 67). In Blake’s color-printed relief etching the dreamer sits with her head between her knees, a barren tree arching over her as almost a second self. Her dream, to the left, is of a naked woman holding aloft a child, the fruit of satisfied desire, and kissing him. This image, separate from what was once the accompanying text, is sufficient unto itself.

“Joseph of Arimathea Preaching to the Inhabitants of Britain”See Essick, Separate Plates 44-46. is also a separate plate. Its subject is connected to Blake’s early series of small watercolors on British historical subjects,See Bindman, “Blake’s ‘Gothicised Imagination’ and the History of England,” William Blake: Essays in Honour of Sir Geoffrey Keynes, ed. Morton D. Paley and Michael Phillips (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973) 29-49. to a list of such subjects in his Notebook (E 672), and to “The History of England, a small book of Engravings,” advertised in his 1793 prospectus (E 693) but not known to exist. It is one of many examples of Blake’s linking Britain with the world of the Bible. Joseph of Arimathea in all three synoptic gospels asks Pilate for the body of Jesus, as in Matthew 27.59-60: “When Joseph had taken the body, he wrapped it in a clean linen cloth, and laid it in his new tomb which he had hewn out of the rock, and he rolled a large stone against the door of the tomb, and departed.” According to legend, Joseph took the Holy Grail to England with him.See Damon, A Blake Dictionary 224-25. Damon does not think Joseph of Arimathea is the subject of this print, but in this he is alone among Blake scholars. He planted his staff in Glastonbury, and it blossomed into a thorn tree. In a drawing of this subject of c. 1780 (Rosenbach Museum and Library),Butlin #76 recto. the basic composition is the reverse of that of the print, in which all the figures are on the same plane and Joseph, on the far right, extends his right arm to point above and beyond them. The white of Joseph’s garment brings his image forward, accentuating the drama of his preaching the Word. The spectators react with varied expressions—concern, deep reflection, faith, and shared wonder. The viewer would need to know the subject of the print, but little more, to appreciate it fully. This is a small print—the image measures 7.8 x 10.7 cm. on a leaf 34.7 x 24.7 cm. in size. This contrast, far from diminishing the effect of this extraordinary print, increases it.

A fourth separate plate is, unlike the ones mentioned so far, a second state. “The Accusers of Theft Adultery Murder” had first been produced as an intaglio monochrome print entitled “Our End is come” in 1793. The only known copy of this state (Bodleian Library) was bound as the frontispiece of copy B of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, but whether by Blake or by a subsequent owner is unknown.Copy B was bought by Francis Douce from a dealer named Dyer in 1821 and bequeathed by Douce to the Bodleian Library (Bentley, BB p. 298). 1821 is an unusually early date for the third-party sale of a Blake, especially considering this one’s rarity. In the second-state impression from the Large Book heavy coloring makes the clouds to the figures’ left black and those above fiery red. Something terrible (all the more so for being unseen) up ahead is producing these signs of destruction. Blake typically thought of accusers as threefold, as in Jerusalem plate 93, where the image of three pointing men is inscribed “Anytus Melitus & Lycon thought Socrates a Very Pernicious Man …” (E 253). In the print from the Large Book the leftmost figure wears a Roman soldier’s tunic and holds a spear. Next to him is a crowned king, unarmed, wearing a suit of armor and a red cape and holding his hands to the sides of his head in horror. The third man, his face contorted in fear, is bare to the waist, holds a sword, and wears blue breeches. All three wear sandals. We are looking at a king flanked by his guards, all three impotent before whatever is approaching. At some time this print bore the title inscription “When the senses are shaken / And the soul is driven to madness”, with “Page 56” to the right of it.See Essick, Separate Plates 31, 36. This page number refers to Blake’s own “Prologue, Intended for a Dramatic Piece of King Edward the Fourth” (E 439) in Poetical Sketches, where the lines are preceded by “O For a voice like thunder, and a tongue / To drown the throat of war!” The warlike men in Blake’s print are already close to madness, as their faces show, and they will not stand.