Two Newly Discovered Advertisements Posted by William Blake’s Father

Wayne C. Ripley (wripley@winona.edu) is a professor of English at Winona State University in Minnesota. He is working on a project regarding Blake’s Broad Street family, friends, and neighbors.

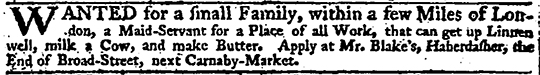

On 23 and 24 April 1773, the following advertisement appeared in the Daily Advertiser :

In the spring of 1773, the Blake family was indeed smaller than it had been, with two of James and Catherine Blake’s five surviving children apprenticed. James Blake, Jr. (1753–1827) had been apprenticed to the needlemaker Gideon Boitoult on 19 October 1768, and William had entered his apprenticeship with the engraver James Basire the previous summer, on 4 August 1772.G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004) [hereafter cited as BR(2)] 11, 12. Three children remained at home. John (1760–?), whom William would call “the evil one,”The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman, newly rev. ed. (New York: Anchor-Random House, 1988) 721. was thirteen; Robert (1762–87), William’s beloved brother who would die with William at his bedside, was ten; and their sister, Catherine Elizabeth (1764–1841), who would live with William and his wife, Catherine Sophia (1762–1831), in Felpham, was nine.

The need for a maid at this moment is unknown. James Blake was presumably doing well in his business. He had sold Banks ribbons in July 1772,Chambers 1: 143 and Bentley, “William Blake of the Woolpack & Peacock.” and he had been able to pay the apprentice fee for William, which had been more than fifty pounds.Michael Phillips, William Blake: Apprentice and Master (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2014) fig. 10. See also BR(2) 12-14. It is possible that the Blake family had previously had a maid, whom they were now simply replacing. George Richmond reported William Blake’s speaking of “an old nurse.”BR(2) 11. If this old nurse ever existed, she may have performed some of the duties mentioned in the advertisement, and the age of the children may have removed the need for a nurse after her death. If the death of the nurse coincided roughly with Blake’s entering his apprenticeship, it may have contributed to his mythological contrasting of young male adulthood with death, old age, women, and children.

The advertisement provides evidence that the Blakes owned a cow, which they or a servant milked. The phrase “a Place of all Work” was common in the late eighteenth century. In 1771, Catherine Jemmat’s Miscellanies describes a “poor girl” saying, “as I had a good share of health and spirits, I did very well in my place, and got so much the good-will of my mistress, that she told me, it was a pity I should be in a place of all work, and that she would endeavour to recommend me into some genteel family.”Catherine Jemmat, Miscellanies, in Prose and Verse (London, 1771) 67. The phrase indicates, then, a clear marker of class that James Blake, at least, was comfortable using. Presumably, given the lack of subsequent advertisements, the position was filled, but by whom and for how long are unknown. If this maid remained with the family until the end of William’s apprenticeship in August 1779, they would have occupied the house together. She may have been doing the domestic work during Blake’s early career as an artist and engraver.

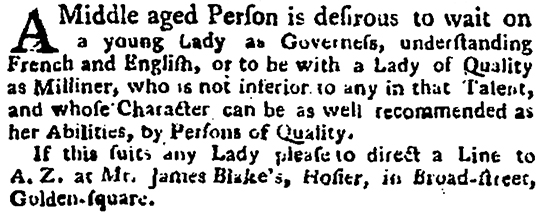

Less than two years later, another murky glimpse into the lives of the Blakes is found when James Blake posted a new advertisement:

Another possibility is a milliner and haberdasher named Mary Blake. In the bankruptcy notices of December 1764, she is listed as “of Winchester.”St. James’s Chronicle or the British Evening Post 8-11 Dec. 1764. By the end of the month, her creditors were working toward the appointment of a person in Winchester “to sell and dispose of the Bankrupt’s Stock and Effects there.”London Gazette 25-29 Dec. 1764. By March 1765, she had met the terms and was granted an allowance under the Bankruptcy Act,London Gazette 9-12 Mar. 1765. and in March 1771 she was listed as paying her final dividends to creditors at Guildhall.Craftsman or Say’s Weekly Journal 2 Mar. 1771. Interestingly, in June 1769, a “Mrs. Blake” of Tooley Street, Southwark, also auctioned her haberdashery and millinery goods and the lease of her house and shop because of bankruptcy.Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser 14 June 1769. She was either the same Mary Blake of Winchester, who had moved to London, or another female Blake with haberdashery and millinery skills who entered bankruptcy during the same period as Mary. This Mrs. Blake’s connection to Southwark may make her a relative of James Blake. His parents had married at St. Olave, Southwark; his mother had been christened in Southwark and his father in Rotherhithe.BR(2) xxx-xxxii, 2. In addition to this Mrs. Blake, other Blakes lived on Tooley Street as well.In 1751, Leonard Blake, who had been “an eminent Merchant in Tooley Street, Southwark,” died (Penny London Post or the Morning Advertiser 27-29 Mar. 1751). Browne’s General Law-List lists an attorney, Richard Blake, at 11 Tooley Street in the 1782 and 1787 editions. Perhaps the most noteworthy was Richard Blake, another haberdasher, who was coincidentally listed as bankrupt just a month before the June 1769 auction of Mrs. Blake’s goods.Lloyd’s Evening Post 12-15 May 1769. Bentley lists three sets of Richard and Mary Blakes who had sons named William christened in St. Olave between 22 May 1768 and 29 August 1779.BR(2) 831. But the advertisement for the auction of “Mrs.” Blake’s lease does not mention her husband, if she had one, or his profession, and I could find no further details on Richard Blake’s business or bankruptcy. Whether Mary Blake and Mrs. Blake were the same woman or different women, their activities between 1771 and 1775 and their relationship to James Blake, if any, are unknown. But would bankrupt status necessitate the pseudonym?

One last possibility for the middle-aged woman in Blake’s immediate family is his mother, then forty-nine. With her daughter having just turned eleven on 7 January, would Catherine want to work as a governess or a milliner for a lady? William had entered Henry Pars’s drawing school at ten, presumably to begin training for his profession. James and William had entered their apprenticeships around fifteen, which would be John’s age in two months as well. If the advertisement does refer to Catherine Blake, it would give some clue as to her own talents and aspirations. The advertisement would also indicate that she knew French. Bentley suggests that there may have been some relationship between the Blakes and the French Huguenot Butchers (or Bouchers) from whom William’s wife, Catherine, descended. James Blake shared his first haberdashery shop and house with a Butcher, and William himself resided with a “Boutcher” in Battersea in 1781.BR(2) 1, 6-7. Catherine could have picked up French from these relatives of her husband. A governess position would also suggest that she enjoyed teaching and working with children, and perhaps she desired to continue to do so if she understood her own children as grown. While all this is speculative, can anything of James and Catherine’s relationship be read into the two advertisements together? If there was no “old nurse” or maid before 1773, had Catherine, who described herself as “a pore crature and full of wants”Keri Davies and Marsha Keith Schuchard, “Recovering the Lost Moravian History of William Blake’s Family,” Blake 38.1 (summer 2004): 40. as a woman of twenty-seven applying to the Moravian Church in 1750, been doing the work of a maid for most of her second marriage? And did she now desire to do her own work apart from her husband? Or was this an effort to drum up further connections and business not only for Catherine but for the family shop as well? We know that Catherine had a prominent role in the shop after her husband’s death, since James Blake, Jr., signed an April 1785 business letter to the Parish of St. James “for Mother & Self.”BR(2) 38.

Perhaps the strongest argument against Blake’s mother being the middle-aged woman is the lack of evidence documenting her skill as a milliner. But as the recent research into Blake’s wife, Catherine, has suggested, Blake trained and encouraged her to develop skills in order to work alongside him and, significantly, on her own.Angus Whitehead, “‘an excellent saleswoman’: The Last Years of Catherine Blake,” Blake 45.3 (winter 2011–12): 76-90; Mark Crosby and Angus Whitehead, “Georgian Superwoman or ‘the maddest of the two’? Recovering the Historical Catherine Blake, 1762–1831,” Re-Envisioning Blake, ed. Mark Crosby, Troy Patenaude, and Angus Whitehead (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2012) 83-107; Helen P. Bruder and Tristanne Connolly, “Introduction: ‘Bring me my Arrows of desire’: Sexy Blake in the Twenty-First Century,” Sexy Blake, ed. Helen P. Bruder and Tristanne Connolly (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2013) 7; Angus Whitehead and Joel Gwynne, “The Sexual Life of Catherine B.: Women Novelists, Blake Scholars and Contemporary Fabulations of Catherine Blake,” Sexy Blake 193-210; Morton D. Paley and Mark Crosby, “Catherine Blake and Her Marriage: Two Notes,” Huntington Library Quarterly 78.3 (2015): 479-91; Ashley Reed, “Craft and Care: The Maker Movement, Catherine Blake, and the Digital Humanities,” Essays in Romanticism 23.1 (2016): 23-38. Did Blake have a model of this type of relationship in his own parents? If not in his parents, we know, at the very least, that his father promoted the career of one talented middle-aged woman, whoever she may have been.