William Blake’s Visionary Landscape near Felpham

Jonathan Roberts (roberts@liv.ac.uk) is senior lecturer in the School of English, University of Liverpool.

Perhaps the most striking account of a religious vision that Blake offers is a poem enclosed in an 1800 letter to his friend and patron Thomas Butts. This rare moment of autobiographical verse, usually referred to by its first line, “To my Friend Butts,” describes Blake’s vision on the beach at Felpham. The poem is well known beyond Blake studies, as it occurs more frequently in anthologies of mysticism than any other passage from his work (with the possible exception of the opening lines of “Auguries of Innocence”). Yet within Blake studies it has received comparatively little scholarly attention. This may be due in part to its anomalous character, something that it shares with another work from the same period and place: Blake’s pencil and watercolor sketch Landscape near Felpham. I argue below that there is a significant and demonstrable relationship between these two works, and that this connection offers a valuable resource for reflection on our treatment of the relationship between the material and the transcendent in our discussion of Blake.

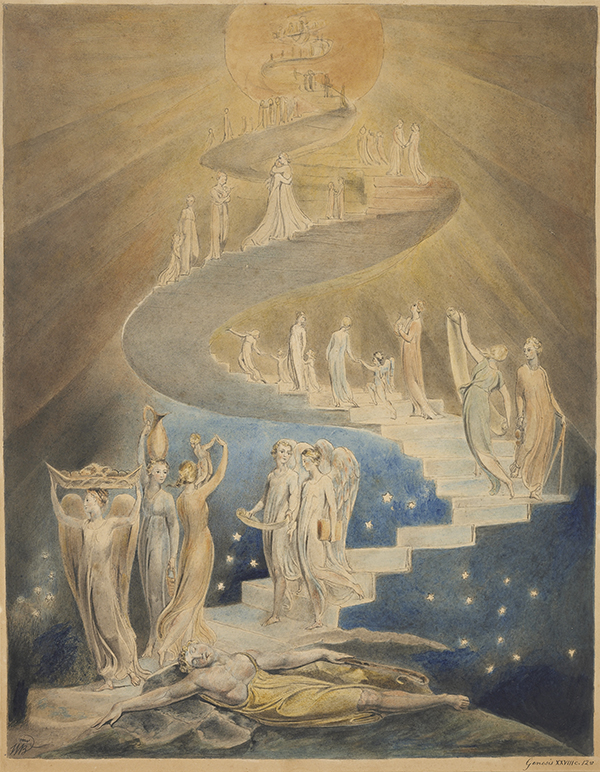

My argument will be in three parts. Part I connects “To my Friend Butts” to its biographical and biblical contexts and shows the ways in which it is in dialogue with Butts’s own overlooked poem to Blake. Part II provides a detailed analysis of Landscape near Felpham, establishing Blake’s position and perspective when making the sketch, demonstrating its visual accuracy, then dating it by relating its minutiae (foliage, tide, weather, and so on) to historical records. I thereby show that although they are not usually linked, the poem and the sketch were probably made on the same morning, on the shore at Felpham on one of the days leading up to Thursday, 2 October 1800. Part III looks at the broader correspondence of the period, in which Blake draws on Genesis 28 (Jacob’s ladder) to negotiate his new life situation, and I use his watercolor of that story to reflect on the poem to Butts and the Felpham sketch. I then connect the vision of God/Jesus at Felpham to its surprising reappearance as a vision of Satan in Milton. I conclude by reflecting on these different elements and by suggesting that the popular and academic reception of Blake’s religion is at odds with the hermeneutic of his Christological “fourfold vision.”

I. “To my Friend Butts”

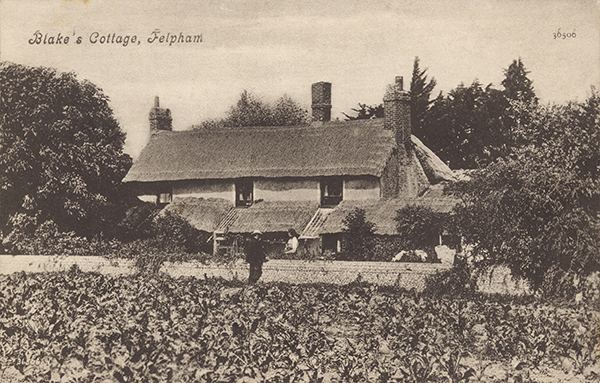

Blake’s three-yearFrom September 1800 to September 1803; his subsequent trial was held in Chichester on 11 January 1804 (see Bentley, Blake Records 179). stay at Felpham has long been considered a turning point in his life, through disillusionment, depression, the incident with Schofield the soldier, and through what Jean H. Hagstrum called a “genuine conversion” whereby “anger, energy, action” impelled him to “become once again the dedicated artist-prophet.”Hagstrum 322. Blake and his wife, Catherine, moved from their London home to Felpham on Thursday, 18 September 1800. On 23 September Blake sent a letter to Butts recounting the “chearfulness & welcome” of the journey, the beautiful countryside, glorious weather, and, in some detail, the excellence of their cottage. The villagers, air, wind, trees, and birds are all mentioned, and in the days following their arrival Blake’s wife and sister, conscious of the fashion for bathing at nearby Bognor,Blake to George Cumberland, 1 Sept. 1800 (Bentley, Blake Records 95-96). Alternatively, they may have been prompted by William Hayley: Catherine had “Exhausted her strength” (Blake to Hayley, 16 Sept. 1800 [E 709]), and Hayley, on “any and every occasion, … would ‘plunge into the ocean’, and he would, moreover, encourage others to plunge. What is more, he would thus plunge at periods which, to our softer ideas, seem positively inhumane. October bathing, for instance, was nothing to him” (Bishop 96). Bognor would later become Bognor Regis when George V went there to convalesce in 1929, as it was thought that the sea air would, likewise, be good for his health (see, for example, <http://www.bognorregis.gov.uk>, under “History”). had already visited the seashore “courting Neptune for an Embrace.”Blake to Butts, 23 Sept. 1800 (E 711). Butts replied within a week with a letter that Basil De Selincourt rightly describes as “a cordial, jocular epistle,” adding, however, that it is “in not too perfect taste,”De Selincourt 274. presumably due to Butts’s preoccupation with imagining Mrs. Blake in the heated embraces of Blake, of Neptune, and of Butts himself. Butts writes:

I am well pleased with your pleasures, feeling no small interest in your Happiness, and it cannot fail to be highly gratifying to me and my affectionate Partner to know that a Corner of your Mansion of Peace is asylumed to Her, & when invalided & rendered unfit for service who shall say she may not be quarter’d on your Cot—but for the present she is for active Duty and satisfied with requesting that if there is a Snug Berth unoccupied in any Chamber of your warm Heart, that her Portrait may be suspended there, at the same time well aware that you, like me, prefer the Original to the Copy. Your good Wife will permit, & I hope may benefit from, the Embraces of Neptune, but she will presently distinguish betwixt the warmth of his Embraces & yours, & court the former with caution. I suppose you do not admit of a third in that concern, or I would offer her mine even at this distance. Allow me before I draw a Veil over this interesting Subject to lament the frailty of the fairest Sex, for who alas! of us, my good Friend, could have thought …The couplet is the finale to Butts’s struggling attempt to stage-manage the sustained innuendo concerning Mrs. Blake; he is more at ease with the metaphors drawn from his job as chief clerk to the commissary general of musters.

So Virtuous a Woman would ever have fled

from Hercules Buildings to Neptune’s Bed?Hercules Buildings was the Blakes’ residence in London. Butts returns to the image at the end of the letter: “Mrs Butts greets your Wife & charming Sister with a holy Kiss and I, with old Neptune, bestow my Embraces there also” (Butts to Blake, Sept. 1800 [Letters 25-27]).

Alongside this giggly flirtation, Butts includes a well-meant poem blessing Blake and Catherine, wishing them long life and visions, and imagining their ascent, after death, to heaven:

Happy, happy, happy Pair,These are strange images to communicate to a friend, because by hoping that Blake’s and Catherine’s bodies will not singe or crack in demonic fires, Butts has imagined that very scenario. G. E. Bentley, Jr., who has contributed so much to our knowledge of Butts, depicts him as a “white collar Maecenas” who, in “the grey years when reputation and even employment were hidden to Blake, … befriended and supported perhaps the most independent and extraordinary genius that ever offered wisdom for sale in the empty market place where none come to buy.”Bentley, “Thomas Butts, White Collar Maecenas” 1066. The homily is entirely justified, but, like Wordsworth’s epitaphic paradigm of “truth hallowed by love—the joint offspring of the worth of the dead and the affections of the living” (Essays upon Epitaphs), it can occlude intriguing aspects of Butts’s character. In particular, it is interesting to ponder what enabled Butts—unlike so many contemporaries—to recognize the genius of Blake’s work. It may well be that in this one surviving letter from ButtsThe original is not extant; Butts, however, retained the draft and kept it with the letters he received from Blake (Letters 27n1). It is, as Bentley puts it, “an undated draft which begins in a beautiful, clerkly copperplate hand and degenerates, through many deletions … to hasty pencil at the end … later darkened in ink” (Blake Records 102fn). we have an answer: he himself had a barely containable imagination that even in a single correspondence is entertaining a ménage à trois with his friends, their consummation in hellfire, and their ascent into heaven.

On Earth, in Sea, or eke in Air,

In morn, at noon, & thro’ the Night

From Visions fair receiving light,

Long may ye live, your Guardians’ Care,

And when ye die may not a Hair

Fall to the lot of Demons black,

Be singed by Fire, or heard to crack,

But may your faithful Spirit upward bear

Your gentle Souls to Him whose care

Is ever sure and ever nigh

Those who on Providence rely,

And in his Paradise above

Where all is Beauty, Truth & Love,

O May ye be allowed to chuse

For your firm Friend a Heaven-born Muse,

From purest Fountains sip delight,

Be cloathed in Glory burning bright,

For ever blest, for ever free,

The loveliest Blossoms on Life’s Tree.Letters 26-27.

Blake’s reply of 2 October, like Butts’s original, mixes humor with seriousness, reflecting the contractual relationship between the two men, the literary aspirations of each (they both enclose poems), their fondness for each other and each other’s wives, and the desire that they have to impress one another. As Bentley puts it, the “relationship revealed in these letters is one of close mutual friendship and cordiality, with every sign of having been established for some time.”Bentley, “Thomas Butts, White Collar Maecenas” 1055. The exchange is reciprocal: Butts, who would later buy a copy of Songs, may well be nodding to “The Tyger” in his line “cloathed in Glory burning bright,” while Blake’s gentle, jovial reply in turn picks up images and ideas from Butts’s letter, with Blake describing himself as “the determined advocate of Religion & Humility”—tongue in cheek, I suspect—in response to what Bentley calls the “somewhat fulsome moral advice” offered by Butts.Bentley, “Thomas Butts, White Collar Maecenas” 1055. After mentioning settling into the new cottage and apologizing for not having completed Butts’s recent commissions, Blake offers his “return of verses” that constitute the poem “To my Friend Butts.” The poem describes Blake’s “first Vision of Light” while sitting on the sands at Felpham. Gazing at the sea, he sees the particles of the sun’s light revealed as human forms—“Heavenly Men”—who beckon to him and illuminate the human reality of all natural phenomena (“Cloud Meteor & Star / Are Men Seen Afar”). Approaching—or perhaps following—them, Blake finds himself looking down upon the village from above, seeing “Felpham sweet / Beneath my bright feet” (emphasis mine), sensing there the “Shadows” of himself, his wife, sister, and friend, and reflecting that we “like Infants descend / … on Earth.” The heavenly men eventually coalesce as one divine man, who enfolds Blake to his bosom. The poem ends, and without further comment, Blake’s letter returns to the matter of commissions, the cottage, the weather, and so on, before concluding with a second, much shorter verse, addressed to Mrs. Butts. The poem and the containing letter are appended to this article, but the section of the poem that is most commonly anthologized is the opening:

The less frequently quoted ascent into the divine bosom that follows is described in this way:This unique lyric vision offers a poetic report of a personal religious epiphany in a specific locale, which took place, presumably, in the days immediately preceding the composition of the letter.The poem picks up imagery from Butts’s letter, which, although undated, must have been written between 24 September (after receipt of Blake’s, postmarked 23 September) and 30 September (to have been delivered in time for Blake to have composed a reply by 2 October); see also Bentley, Blake Records 102fn. The poem owes its first-person, loco-descriptive character, so unusual in Blake, to its occurrence halfway through a letter to a friend. It has other notable features too: it refers to the poet’s wife, sister, and friend, and the catalyst to the vision is an experience of the natural world. All these are characteristics that we might expect of, say, a conversation poem, and in the wider romantic context, none of them is unusual. We are quite used to this sort of setup in the work of other poets of the period (Wordsworth’s “Lines Written a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey” and Coleridge’s “The Eolian Harp” are obvious examples). In Blake, however, it is a rarity. Elsewhere, we have many reports of Blake’s visions; individuals such as Henry Crabb Robinson and Alexander Gilchrist recount tales about the boy Blake’s being terrified by God poking his head in at a window or delighted by finding angels up a tree. But as a firsthand, to-the-moment account of being caught up into heaven from Felpham and looking down at the village from above, this poem is unique among Blake’s writings. Moreover, the first-person narrative voice is different from that of the Blake to whom quotations are often attributed, for this is neither the voice of the devil, nor a song of innocence, nor the dramatized narrator of one of the prophecies. It was not written for publication, but is more like the semi-private effusion of Wordsworth’s “Distressful gift! this Book receives.” Its intimate character gives it a special place in his oeuvre, and, consistent with the letter in which it is found, its privacy and inwardness show us things less often seen in Blake.

Our understanding of “To my Friend Butts” may be enhanced by considering its companion piece, the rarely discussed poem for Mrs. Butts that Blake encloses in the same letter. “Mrs Butts,” he writes, “will Excuse the following lines”:

Wife of the Friend of those I most revere.One way to read this overlooked poem is as a disarming of Butts’s bit of innuendo. Declining to sustain the banter about embracing Neptune, Blake instead writes a rather chaste verse about Mrs. Butts, reasserting her proper place as the wife of his revered friend. With that established, he is able to praise her pedagogical,“Betsy [Butts] had a boarding school for girls at 9 Great Marlborough Street at which Blake may have taught and which was decorated with his drawings” (Bentley, Blake Records 90). maternal, and matriarchal fruitfulness—all this in the language of fertility—without turning his verse to her body or sexuality.A final note on the tenor of the poem. Blake, perhaps unsurprisingly given his new setting—by the sea and cornfields—uses images of water and of harvest. The mention of “Springing to Eternal life” echoes John 4.14 (“whosoever drinketh of the water that I shall give him shall never thirst; but the water that I shall give him shall be in him a well of water springing up into everlasting life”). Likewise, the invocation to “Go on in Virtuous Seed sowing … / … & Behold / Your Harvest Springing to Eternal life” evokes numerous New Testament passages, not least the parable of the sower in Matthew 13.2-9, a passage that—with a wonderful appropriateness given the context—is immediately preceded by the line “The same day went Jesus out of the house, and sat by the sea side.” All quotations from the Bible are from the Authorized (King James) Version. This response may provide a helpful cue for thinking about how “To my Friend Butts” is responding to Butts’s “Happy … Pair.” Butts’s poem is surprisingly carnal in its imagined burning of his friends’ flesh, and just as Blake’s verse to Mrs. Butts seeks to limit the sexual life of his friend’s letter, so “To my Friend Butts” may likewise be neutralizing the apocalyptic elements of Butts’s vision by bringing that vision out of the future into the present and out of heaven and hell back to Felpham. There may be both an element of good-humored visionary one-upmanship here and a practical demonstration by Blake of what vision is. There is also, though it goes against the grain of a widely cherished image of Blake, a unique instance of the great champion of unfettered imagination and supposed advocate of free love attempting to tone down and rein in the fantasies of his patron and friend.Even Val, the renegade of Marilyn French’s The Women’s Room, who “saw the whole world in terms of” sex, “used to say that only Blake had known what the world was really about” and “read Blake at night: the book lay always on her bedside table” (chapter 16). The situation is only complicated by (i) Blake’s later (1809) picture of the whore of Babylon, which bears a striking resemblance to Mrs. Butts, although Bentley decides this “must be coincidental” (caption to pl. 75, The Stranger from Paradise), and (ii) the romantic overtones of Blake’s “The Phoenix to Mrs Butts.” Joseph Viscomi notes that perhaps “it is not a coincidence that the couplets of Blake’s other verses have three or five beats to the line, whereas those of ‘The Phoenix’ have four, the same number of accents as in the couplets of Thomas Butts’s poem to Blake.” Moreover, he says that “Mr. Butts also wrote Blake a poem, included in a September 1800 letter, explicitly acknowledging his affection for Catherine Blake and Blake’s affection for Mrs. Butts—acknowledgments not without double entendres” (Viscomi 15). The affection that Viscomi mentions is expressed in the letter rather than the poem. What is certain is that the two poems are in dialogue, and that our understanding of “To my Friend Butts” can be deepened through consideration of its response to the narrative and imagery of Butts’s “Happy … Pair.”

Recieve this tribute from a Harp sincere

Go on in Virtuous Seed sowing on Mold

Of Human Vegetation & Behold

Your Harvest Springing to Eternal life

Parent of Youthful Minds & happy Wife

This dialogue is especially evident in the shared religious (and specifically biblical) imagery that the two men deploy, which both provides common ground and marks out their differences. Butts’s poem uses the second person in an imagined future and draws on the book of Revelation to narrate his hope that after their deaths the Blakes will ascend to heavenHe uses “Paradise above” rather than “heaven,” but the synonymity is clear from the other details and has biblical precedents in, for example, the crucifixion narrative of Luke 23.42-43: “And he said unto Jesus, Lord, remember me when thou comest into thy kingdom. And Jesus said unto him, Verily I say unto thee, To day shalt thou be with me in paradise.” and be united with God. The narrative structure—judgment and burning, ascent and glory—also echoes the final chapters of the New Testament, in which the casting of the devil into the lake of fire and brimstone in chapter 20 is followed by the description of the new heaven and earth in chapters 21 and 22. The picture of heaven that Butts unfolds, in which the Blakes will from “purest Fountains sip delight” and become the “loveliest Blossoms on Life’s Tree,” appears to be drawn from the crystal-clear river and tree of life of Revelation 22.1-2.“And he shewed me a pure river of water of life, clear as crystal, proceeding out of the throne of God and of the Lamb. In the midst of the street of it, and on either side of the river, was there the tree of life, which bare twelve manner of fruits ….” Likewise, Butts’s hope that the Blakes will be “cloathed in Glory” may relate to the martyrs in Revelation 6.9-11, who are given “white robes,” which also feature in Revelation 7.9-17. He may also be drawing on 1 Corinthians 15 at this point,“For this corruptible must put on incorruption, and this mortal must put on immortality” (1 Corinthians 15.53). a discussion in which Paul, like Butts, is emphatically concerned with death and resurrection, kinds of glory, and being clothed anew. Blake, by contrast, works with a different paradigm of the transformation being wrought on the individual, as he presents not new clothing in his poem, but a bodily union with the “One Man” who enfolds his limbs. Blake, like Butts, has biblical precedents here,For example, Philippians 3.20-21, in which Jesus “shall change our vile body, that it may be fashioned like unto his glorious body.” but his account has a freshness and intimacy with the divine, in comparison with which Butts’s offer of a future encounter with a God “known by his Attributes”“Him whose care / Is ever sure and ever nigh / Those who on Providence rely”; the quotation in the text is from Blake’s critique of Newton’s vision of God in The Everlasting Gospel (E 519). seems like an ideal in a picture book. This shift epitomizes the way in which Blake’s poem fulfills or reimagines the hopes of Butts’s verse: Butts wishes Blake “Visions fair receiving light,” and Blake responds with his own “first Vision of Light”; Butts hopes that after death Blake’s soul will be borne up to heaven, and Blake responds with a full-blown account of how this has already happened, being taken up into God’s bosom as a present reality, not as an imagined afterlife. Butts concludes by wishing that the Blakes will from “purest Fountains sip delight”; Blake closes by recounting how he “saw you [Butts] & your wife / By the fountains of Life.” In sum, Blake reclaims Butts’s narrative by retelling it in the present, in the first person, and by offering an immediate, earthly realization of the eschatological promises of Butts’s poem. This is a marked contrast from Butts’s vision because, for Blake, our place in heaven does not have to come at the expense of our place in the world.I will return to this continuity of the eternal and the everyday when discussing the relationship of the poem to the sketch.

Acknowledgment of this biblical dialogue is important because it has largely been lost in the reception history of the poem.The poem occasionally appears in scholarly publications, but is usually discussed in passing, often in the demonstration of some larger theory of Blake’s work (see, for example, Frye 42). Kathleen Raine picks it up in a footnote in Blake and Tradition, linking Blake’s imagery of the “One Man” (line 51) to the work of Swedenborg, speculating that Blake may have read Newton’s Opticks during his residence at Felpham, and noting that the particles of light (line 19) have Newtonian resonances (Raine 1: 420-22). In one of the few sustained discussions of the poem, Donald Ault’s Visionary Physics relates these resonances to Blake’s theory of fourfold vision, a theme also discussed by David Wells in A Study of William Blake’s Letters. De Selincourt provides some helpful observations on the poem in William Blake, and Stephen D. Cox, who looks at the visionary logic of the poem, suggests it is “the clearest, least mediated, literary record we have of a Blakean vision” (Cox 31). In Symbol and Truth in Blake’s Myth, Leopold Damrosch, Jr., provides perhaps the fullest reading of the poem as the testimony of a biographical event and attempts to analyze the kind of experience that Blake is recounting. My earlier discussion of the biblical imagery of “To my Friend Butts” is in Blake. Wordsworth. Religion. 75-80. “To my Friend Butts” has remained a staple of popular anthologies of mystical verse over the last century, from The Oxford Book of English Mystical Verse (1917) to Poetry for the Spirit (2002), and, as the title of the latter suggests, has been widely admired in what might be called new-age publications.See, for example, the 1963 article in the Theosophist journal, which quotes the poem and then comments, “To know ourselves fully as the One Heavenly Man is the goal of our return journey. On the outward journey, the Monad through the Ego discovers the circumference, the not-Self, the many. On the return journey he rediscovers that the many are the One” (Galloway 92). This has been facilitated by the abridgment of the second half of the poem, an abridgment that foregrounds the generic mystical featuresI mean the sorts of characteristics categorized by William James (see James 329). while obscuring the biblical dialogue that is taking place. Recovering this dialogue enriches and clarifies the meanings of the poem,As Robert N. Essick and Viscomi write about Milton, “much of the code of Milton remains obscure unless we attend to the Bible” (Essick and Viscomi 13). as two instances will demonstrate. First, Blake’s ascent above Felpham. Appearing initially in the third-person stories of Enoch (Genesis 5.24) and Elijah (2 Kings 2.11), accounts of being taken in vision up into heaven are given in the first person by Ezekiel, Paul the Apostle, and John of Patmos.For a fuller discussion of Blake’s interest in Enoch and the ascent of Enoch through the palaces of heaven in 1 Enoch, see Rowland. Ezekiel, for example, is lifted up by the spirit and taken into vision,“And he put forth the form of an hand, and took me by a lock of mine head; and the spirit lifted me up between the earth and the heaven, and brought me in the visions of God to Jerusalem” (Ezekiel 8.3). and Paul and John record comparable experiences in 2 Corinthians“I will come to visions and revelations of the Lord. I knew a man in Christ above fourteen years ago, (whether in the body, I cannot tell; or whether out of the body, I cannot tell: God knoweth;) such an one caught up to the third heaven. And I knew … how that he was caught up into paradise, and heard unspeakable words, which it is not lawful for a man to utter” (2 Corinthians 12.1-4). and in Revelation.“After this I looked, and, behold, a door was opened in heaven: and the first voice which I heard was as it were of a trumpet talking with me; which said, Come up hither, and I will shew thee things which must be hereafter. And immediately I was in the spirit: and, behold, a throne was set in heaven, and one sat on the throne” (Revelation 4.1-2). Blake’s poem participates in this tradition, sharing the elements of being taken up into heaven or paradise and hearing God speak, then returning to earth to report the news.

Second, the union with (and identity of) the “One Man.” Geoffrey Keynes is only partially right in his assumption that this is “Los, the Spirit of Prophecy.”See Letters 29n1. Keynes derives this from Sloss and Wallis. I will discuss the connection to Los more closely (with reference to Milton) in the final section. The “One Man” often appears in Blake’s work, whether as the “Universal Family” (E 180, 311), “Universal Humanity” (E 377), or as Jesus (E 116, 143). In “To my Friend Butts” the extensive biblical allusions make the identification clear, for although God and Jesus are not explicitly named, there are numerous associations. The “One Man,” like God and Jesus, is figured as a shepherdSee, for example, Psalms 23.1 and John 10.11. (he refers twice to the earth as his “Fold,” and addresses Blake as his “Ram”).The language of mountain, sea, wolf, and sheep in the poem is also found in Isaiah 11, which anticipates the Messiah. Blake’s encounter with him is, moreover, personal and intimate: Blake rests in his “bosom” just as Lazarus rests in the bosom of Abraham (Luke 16.22) and as the beloved disciple rests in the bosom of Jesus at the Last Supper (John 13.23). The passage itself has a baptismal character, as Blake’s “mire” and “clay” are “Like dross purgd away,” and the central vision of light reflects visionary encounters with God and Jesus found throughout the Bible. The visions of Ezekiel, Paul, and John mentioned above are likewise all associated with light;The spirit that lifts Ezekiel is “a likeness as the appearance of fire: from the appearance of his loins even downward, fire; and from his loins even upward, as the appearance of brightness, as the colour of amber” (Ezekiel 8.2). During Paul’s conversion near Damascus “suddenly there shined round about him a light from heaven” (Acts 9.3), and Jesus Christ, who appears to John, is described in these words: “His head and his hairs were white like wool, as white as snow; and his eyes were as a flame of fire” (Revelation 1.14). Moses’s encounter with God leaves his face shining (Exodus 34.29ff.), an image recapitulated in the transfiguration of Jesus, whose “face did shine as the sun” and whose “raiment was white as the light” (Matthew 17.2), and by Blake in the preface to Milton, which asks (about Jesus) “did the Countenance Divine, / Shine forth upon our clouded hills?” (E 95). The association of Jesus with light is also central to the Gospel of John.“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. … In him was life; and the life was the light of men. And the light shineth in darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not. … That was the true Light, which lighteth every man that cometh into the world” (John 1.1-9).

In sum, “To my Friend Butts” is suffused with biblical imagery, and that imagery is not limited to the poetic moment but is part of a wider discussion that carries through into Blake’s correspondence of this period. In part III I will be extending this discussion to look at the central organizational metaphor of this poem and of Blake’s wider correspondence, before relating it to Blake’s contemporary sketch Landscape near Felpham, to which I now turn.

II. Landscape near Felpham

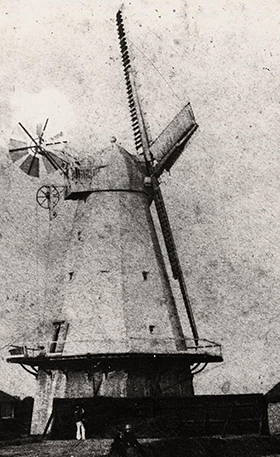

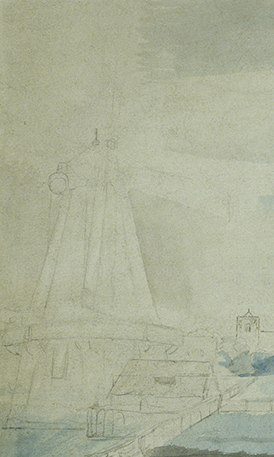

Landscape near Felpham (illus. 1) is a sketch in pencil with a watercolor wash. It depicts the view toward Felpham from the south, looking across cornfields to (from left to right) White Mill and an outbuilding,This was perhaps the largest smock mill ever built in Sussex (a smock mill is typically wooden, tapered, and hexagonal or octagonal in plan). See Blythman 45. Including the cap and two-storey base, it appears to have been seven storeys tall. the tower and church of St. Mary the Virgin, Hayley’s new villa, the Turret (later known as Turret House), and, to the right, the Blakes’ cottage.The identification is made in Butlin 1: 313 (#368). The sketch is faint, but the mill, trees, tower, church, and cottage are all quite clear. Some details are less obvious. The rough brushstrokes in the foreground represent the sea, and there is the most elementary boat to the right, with a large oblong shape over it that is difficult to make out: it might represent a cow grazing, or possibly a shrub (at the bottom right of this unpainted rectangle is a pencil detail that could depict either an animal’s legs or the stems of a plant). In the left foreground there is vegetation on the shoreline. A fence runs across the field, and a little right of center is a rider on a horse (riding right to left). Between the rider and the mill two figures, perhaps, stand against the fence. On the right of the field, and slightly more distant, might be another figure or animal. There are clouds and sunshine, with rays of light falling on the cottage. The pencil elements of the sketch are naturalistic and attentive to detail: the original winding device of the mill and the abat-son (although not the crenellation) of the church tower, for example, are both visible.

The Felpham sketch is, in some respects, Blake’s most ordinary picture, prompting Raymond Lister to write that the scene “amply demonstrates what the main body of his work has led some to doubt, that he was capable of painting straightforward landscapes.”Lister pl. 25. Blake, as far as we know, rarely sketched his surroundings. The examples that we do have are principally of Hayley’s previous house, at Eartham, and appear to have been made for the latter’s records.In Butlin there are a number of sketches from c. 1801 that were probably made on the same day as one another when Blake visited Eartham (see 1: 313-14, #369-73). Yet the oddness of this “straightforward” romantic landscape sketch only really becomes apparent against the wider backdrop of Blake’s visual art. In the 1990s, the Blake room at the Tate was dominated by the great color prints that include Elohim Creating Adam, The Good and Evil Angels, Newton, and Nebuchadnezzar, and the temperas of The Spiritual Form of Nelson Guiding Leviathan and The Ghost of a Flea. Then—in a sudden departure from this apocalyptic cosmos—there was Landscape near Felpham. It is a work that seems to step out of Blake’s mythological world and into his everyday life, and like the letter and poem to Butts, it is a private work that discloses a rarely seen side of his character and art. Certainly by the end of the decade, Blake would not have hung the Felpham sketch in an exhibition. The very different kind of public artist that he later wished to be is clear from the 1809 catalogue of his “Exhibition of Paintings in Fresco, Poetical and Historical Inventions.”For example, “if Art is the glory of a Nation, if Genius and Inspiration are the great Origin and Bond of Society, the distinction my Works have obtained from those who best understand such things, calls for my Exhibition as the greatest of Duties to my Country” (E 528). See also David Blayney Brown and Martin Myrone’s discussion in “William Blake’s 1809 Exhibition.”

The central similarity between “To my Friend Butts” and Landscape near Felpham is an obvious one: both describe an experience on the beach at Felpham. Moreover, the relationship of the sketch to Blake’s wider visual oeuvre is similar to the relationship of the poem to his wider literary oeuvre: both offer an atypical first-person account of a local scene, and both forego the characteristic polemical and dramatic elements of Blake’s art. Put in these terms, one might expect the two to have been linked critically, yet they have not.Although the poem and sketch have long been recognized as works from approximately the same place and time, their apparent experiential disparity seems to have discouraged critical investigation of their actual connection. So, for example, when discussing the sketch, Lister (pl. 25) does quote part of the poem, but does not suggest that the two may represent the same moment. Butlin writes that it is “tempting to see this watercolour as Blake’s first reaction to the prospect that opened up with his move to Felpham,” and quotes the letter to Flaxman concerning “Celestial inhabitants” (see paragraph 24, below), but takes this intuition no further (1: 313). I discuss the connection between the sketch and poem in Blake. Wordsworth. Religion. 7-15 and 34-36. So what historical evidence is there that the sketch and poem are two sides of the same coin?

Given the first-person character of these pieces, it is worth beginning with Blake’s location: where was he when he made the sketch, and when did he make it? Frederick Tatham, who vouchsafed the picture, added “subject not known. perhaps near Felpham”; in fact, there is no question of the location, as this is certainly Felpham itself, the village seen from a viewpoint that can be located to within a few meters. The scene can no longer be viewed, not only because the mill and turret no longer exist, but because of the extensive twentieth-century housing that now fills the landscape. Nonetheless, the four fixed points in the sketch—the mill, the church, the turret, and the cottage—are visible on the first edition of the Ordnance Survey County Series map,Ordnance Survey County Series 1:2500, 1st ed. (1854–1901), “Sussex County.” The layout of Turret House can be established from surviving architectural plans and pictures; see Crosby, “The Sketch on the Verso of Blake’s Self-Portrait: An Identification.” and their coordinates can be cross-referenced with modern satellite imagery such as that provided by Google Earth. The exact positions of the buildings can thereby be established,Mill: 50.785652, -0.654725; church: 50.790731, -0.654655; turret: 50.790617,

-0.652571; cottage: 50.788670, -0.652510. These coordinates can be pasted directly into the search bar of Google Earth. as can the distances between them,Mill–church: 560.7 m; mill–turret: 572.8 m; mill–cottage: 362.7 m; church–turret: 149 m; church–cottage: 272.5 m. and this information can be related to their relative positions within the sketch itself. Blake’s position when drawing the sketch can then be estimated using triangulation.We imagine Blake standing facing the scene he is painting, with his sketchbook in front of him. Visual angles between landmarks in the scene will be represented as distances between them on his canvas. Although we can’t know the scale of this representation, given three landmarks we can look for locations where the relative angles between adjacent pairs of landmarks are in the same proportions as those Blake has depicted. This leads to an equation whose solution is a one-dimensional curve on the map. In the painting there are four prominent landmarks, so that we have two such curves, and we conclude that Blake was standing where these curves intersect. There is only one such point from which the landmarks would also be in the same order, left to right, as in Blake’s painting.

So where was Blake standing (or sitting)? The main evidence comes from the sketch itself: in the foreground are waves and a boat, suggesting that Blake himself must have been in a boat, a little out to sea, when he drew the scene. Further out from the shore Felpham beach slopes very gradually; close to the shoreline it shelves steeply, as can be seen in illus. 2, yet Blake has a high eyeline on the scene before him. There are numerous groynes on the beach, but (again, as illus. 2 shows) these would still not provide sufficient elevation for the given eyeline. This suggests that the sketch must have been made at full tide—anything less would have provided insufficient elevation—and indeed the tide appears full in the image. Blake’s approximate position, triangulated from the sketch,50.785471, -0.654257. is a little out to sea, although this evidence is only suggestive, as early nineteenth-century maps of the scene lack detail of the shoreline, and the shore has eroded substantially since 1800, eventually taking the mill with it.Blythman 44. The erosion is quite evident when the Ordnance Survey map is overlaid on a modern satellite image of Felpham. Although the mill was dismantled in 1879, there are a number of surviving images of the building from the nineteenth century. The erosion of the shore can be seen in illus. 2 (Percy Thomas’s 1878 etching), and the sheer size of the mill can be seen by looking at the human figures in illus. 3.

(right) Detail from Landscape near Felpham. © Tate, London 2013.

(bottom) William Blake, Milton copy D (1818), pl. 36, detail. Library of Congress; image courtesy of the William Blake Archive.

Landscape near Felpham © Tate, London 2013. Jerusalem images from the Yale Center for British Art, B1992.8.1(24) and (44).

In summary, Landscape near Felpham provides a number of distinct, though related, kinds of accuracy that can be cross-checked with nineteenth-century maps and photographs. It demonstrates (as perhaps no other work by Blake does) that he could and did sketch landscapes accurately from life, and that he could do so with an impressive precision in terms of spatial relationships, perspective, proportion, and visual detail. This mimetic accuracy offers, moreover, an unusual opportunity in Blake criticism to attempt to date the composition by careful consideration of the other details (tidal, meteorological, botanical) of the picture. Working with the hypothesis that this is a record of a real scene (i.e., as seen by Blake on a particular day at a particular time), we can relate the conditions that are evident in the sketch (i) to one another, (ii) to details in Blake’s correspondence, and (iii) to other sources, such as contemporary newspapers. The date that we derive from this specific combination of temporal details can then be related to the composition date of “To my Friend Butts.”

Let us begin with the year of composition. There are only four possibilities: 1800, 1801, 1802, 1803, as Blake was not in Felpham either before or after these dates. Unlike the letter, the sketch is undated, but has been designated as 1800,Butlin dates the sketch c. 1800 (1: 312). and the logic here seems just: the picture is full of optimism with its open skies and fields and the sunbeams falling on the cottage. The cheerful mood and the uncharacteristic interest in the subject matter are concomitant with the effusive delight over his cottage and setting that Blake expresses in his letters in the weeks before and after his arrival in Felpham. That delight is not present in later correspondence,The one later exception is “Felpham Cottage / of Cottages the prettiest,” 11 Sept. 1801 (E 717). Hayley says, “Our good Blake grows more & more attach’d to this pleasant marine village” (to Flaxman, 18 Oct. 1801 [Letters 37]), but this is part of a pair of open letters that includes content from Blake, who doesn’t pick up on the comment. and this is not simply due to the shine wearing off his surroundings. Blake became unhappy quite quickly, and Catherine was ill for a long period, almost from arrival. Whereas the 1800 letters are full of optimism and delight, the letters of 1801 and 1802 are, as David Bindman puts it, “full of impassioned distress.”Bindman 135. By 22 November 1802 Blake explains to Butts that he has “been very Unhappy & could not think of troubling you about it or any of my real Friends (I have written many letters to you which I burnd & did not send).”E 719. That dark mood carries from the letters into the poetry of the later period, and is manifest in another rare loco-descriptive poem of this time, which offers a fascinating point of comparison to “To my Friend Butts.”In his second letter to Butts of 22 November 1802, Blake specifically states that he has written a poem while walking: “I will bore you more with some Verses which My Wife desires me to Copy out & send you with her kind love & Respect they were Composed <above> a twelvemonth ago [in a] <while> Walk<ing> from Felpham to Lavant to meet my Sister” (E 720). It is a poem that starts in a mood similar to that of 2 October 1800:

With happiness stretchd across the hillsBut like a dark counterpart to Felpham’s “Heavenly Men,” it is the dead who show up, as the pleasant scene of nature rapidly degenerates into visionary horrors:

In a cloud that dewy sweetness distills

With a blue sky spread over with wings

And a mild sun that mounts & sings

With my Father hovering upon the wind

And my Brother Robert just behind

And my Brother John the evil one

In a black cloud making his mone

Tho dead they appear upon my path

Notwithstanding my terrible wrath

They beg they intreat they drop their tears

Filld full of hopes filld full of fears

The visceral force of this later writing is unmistakable, and for these reasons the year of composition of the sketch seems certain to be 1800. But what about the month? We are fortunate in this respect that the sketch shows both trees and crops, and this is consistent with the letters of this period, in which Blake is uncharacteristically detailed about his surroundings. He writes to Cumberland:

I have taken a Cottage at Felpham on the Sea Shore of Sussex between Arundel & Chichester. Mr Hayley the Poet is soon to be my neighbour[;] he is now my friend; to him I owe the happy suggestion, for it was on a visit to him that I fell in love with my Cottage. … We lie on a Pleasant shore[;] it is within a mile of Bognor to which our Fashionables resort[.] My Cottage faces the South about a Quarter of a Mile from the Sea, only corn fields between.Blake to Cumberland, 1 Sept. 1800 (Bentley, Blake Records 95-96).These are the same fields portrayed in the sketch, but there they do not depict acres of waving corn;Blake could draw corn; see, for example, The Blighted Corn in Lister pl. 63(i). rather, they appear to be bare. A rider on a horse trots across the field, and there are no stalks, leaves, or ears of corn visible either generally or around, for example, the base of the fences. This indicates that the sketch was not made during Blake’s initial visit to Felpham in July 1800,He was in Felpham for most of July 1800: “On 5 July 1800, Flaxman sent with Blake a letter and gifts to Hayley, and on 16 July Hayley wrote to Flaxman that ‘our good enthusiastic Friend Blake will … extend the time of his Residence in the south a little longer than we at first proposed’” (Bentley, Stranger from Paradise 208fn). a time at which the corn would have been fully grown. The early harvest was brought in during August,“Agriculture—Monthly report for August. From the uncommon fineness of the weather during the whole of the last month, and the greatest part of the present, the harvest in most places commenced a fortnight or three weeks sooner than usual, and in many of the southern and western districts, on this account, much of the crops have been already secured” (Hampshire Chronicle 8 Sept. 1800). after Blake had gone back to London; therefore the sketch must have been made after he returned to Felpham in mid-September, by which time the fields were being prepared for the following year. Indeed, one of the first events recorded by Blake after his return is seeing the ploughman: “A roller & two harrows lie before my window. I met a plow on my first going out at my gate the first morning after my arrival & the Plowboy said to the Plowman. ‘Father The Gate is Open.’”Blake to Butts, 23 Sept. 1800 (E 711).

This gives us 19 September 1800—the Blakes’ first full day in Felpham—as the earliest date for the sketch, but what is the latest possible date? Here the foliage provides an answer. The trees that are visible in the sketch (and which can be identified on the Ordnance Survey map) are a line of boundary trees. From the sketch, they appear to be deciduous hardwoods, quite possibly the same types of large spreading trees that still grow in the same location today: beech, oak, and horse chestnut. Although these trees would still have been in full leaf in September, the seasonal defoliation would have been quite advanced by the end of October, and given that there are no visible branches or other signs of defoliation in the sketch, it seems reasonable to take the end of October as the latest possible date for the picture’s composition.As the weather had been unseasonably mild, the trees might have held their leaves a little longer. Even so, there are no branches visible on any of the trees in the picture. Certainly all leaves (and many branches) would have been gone by Sunday, 9 November, when a hurricane blew down houses, a mill, a barn, and uprooted 200 “stately oaks” at Glynde Bourne (Hampshire Chronicle 17 Nov. 1800). This establishes a six-week window within which the sketch might have been made, between Friday, 19 September 1800 and Friday, 31 October 1800 (by which time arboreal defoliation would have been clearly visible). Narrowing the timeframe further requires working with a combination of tidal and solar information. The visibility of crepuscular rays in the sketch makes it possible to estimate the position of the sun, as the point of convergence of the rays can be located toward the top right of the picture.“In real skies the crepuscular rays (the bright and dark beams apparently radiating from the sun when blocked by clouds) help one considerably to guess where the sun is, because they cross one another at the solar position. This phenomenon makes it very easy to locate the sun” (Barta et al. 1032). The sketch is made facing north, and the sun is shown to be in the east/southeast in the image, so this is certainly morning, and the elevation of the sun would suggest mid-morning. For the purposes of this discussion I am therefore giving the broad parameters of a time of composition at least an hour after dawn and at least an hour before noon. This timeframe can then be related to the tidal conditions in order to narrow further the date. As I demonstrated earlier, for the sketch to have been made the tide must have been full, and indeed we see it lapping against the field’s edge. The dates on which high water occurred between one hour after dawn and eleven in the morning during the period from 19 September to 31 October are as follows: (i) Tuesday, 30 September to Thursday, 2 October inclusive; (ii) Wednesday, 15 October to Saturday, 18 October inclusive; and (iii) Wednesday, 29 October.Tide timetables (which include times of sunrise and sunset) are available for Bognor for this period, along with tide heights. See <http://easytide.ukho.gov.uk>. The last date is the least likely due to the probability of visible defoliation (of which the sketch shows no evidence). We are left with only two 3-4 day periods during Blake’s three-year stay in Felpham when the sketch could have been made. The first (30 September to 2 October) exactly coincides with the composition of the poem and letter to Butts. The probability of this particular timeframe (rather than the later date) corresponding to the composition of the sketch is further increased, as the details of weather (sunshine and clouds) described in both the letter and the poem it contains coincide with what we see in the picture.Blake writes, “Our Cottage looks more & more beautiful. And tho the weather is wet, the Air is very Mild. much Milder than it was in London when we came away” (to Butts, 2 Oct. 1800 [E 713-14]). On top of this, of course, we know that Blake had been at the location of the sketch at this time because his presence there is the subject of the poem.

What can we conclude from this? It is highly probable that the sketch of Felpham and the poem to Butts were composed within the same three-day period, and it is probable (given consistency of internal details regarding weather and time of day) that the scene they describe refers to the same day. Might they be the visual and literary manifestations of the same biographical experience? At first it seems not, as the sketch indicates that Blake was on a boat, whereas the poem has him on “the yellow sands sitting.” It is difficult to be certain how the shoreline looked in 1800, but today, at least, the “yellow sands” are not visible when the tide is full, as the upper shore is shale. It is possible, of course, that Blake was “on the yellow shale sitting” or “on the yellow shingle sitting” but that he preferred to use “sand,”There is a poetic latitude in the description of the clouds as “Heavens Mountains,” for example. We have no record of Blake’s using the terms “shale” or “shingle” elsewhere. which is such a significant term elsewhere in his work.He uses the word in poems that bear a significant thematic relationship to the subject under discussion; see, for example, the “World in a Grain of Sand” of “Auguries of Innocence” (E 490), and the sands of the seashore (and particles of light) that reflect the “beams divine” and that blow into atheist eyes in “Mock on Mock on Voltaire Rousseau” (E 477). Such an argument need only be made, however, if it is assumed that the epiphany took place in a moment. Yet this is not what the poem narrates. Blake recounts an experience that takes place over time, and that starts out as a vision by the sea, but ends with a vision on it: “Such the Vision to me / Appeard on the Sea” concludes the poem. Perhaps, then, Blake’s vision began on the shore and ended on a boat. But wouldn’t he have mentioned putting out in a boat? Not necessarily, as he makes no explicit acknowledgment of his position in the sketch of the same scene. Perhaps so, but does “on the Sea” mean that Blake was on the sea, or just the vision? Granted, this is ambiguous, though the prepositional structure echoes the opening of the poem, which locates Blake and his “Vision of Light / On the yellow sands.”The poem is more difficult to locate in space and time. The extempore character of the sketch and its visual accuracy indicate that there was no chronological space between the events depicted and the recording of those events, but this is not necessarily the case with the poem. Blake might have written the poem sitting on the beach or on the boat. But he might equally have composed it as part of his letter to Butts back at the cottage later the same day, or a day or two later, though the phrasing of the letter suggests that the poem was already written, as Blake “cannot resist the temptation” of sending it to Butts. No firm conclusions can be drawn here; rather, the subject opens out the great difficulty of discussing recorded “religious” experience: such visions may be autobiographical, but they are also inextricably textual. It is these textual parameters and the continuity of metaphor and image with Blake’s correspondence in this period that I now wish to consider in more detail.

III. Stairway to Heaven

Essick and Viscomi write in their introduction to Milton that “Blake was so fully imbued with the language of the Bible that it is frequently difficult to separate purposeful allusion from the unselfconscious repetition of habitual patterns in many of Blake’s poems.”Essick and Viscomi 13. Indeed, throughout his art and correspondence, the Bible is not so much a subject of discussion as a means to understanding. It is not a static, self-interpreting monolith (the very thing his art contests), but a heuristic resource to understand his own life situation. This is especially evident in the correspondence surrounding the move to Felpham, which shows that the central tropes that Blake employs in “To my Friend Butts”—the ascent to heaven and return to earth, and the interaction of heavenly and earthly beings—neither begin nor end with the correspondence to his patron, but are a more widespread element of his thought at this time, and may be found in the letters that date back to his preliminary journey to Felpham in July.

In July, Blake had written to Cumberland “I begin to Emerge from a Deep pit of Melancholy,”Blake to Cumberland, 2 July 1800 (E 706). and by the time he had reached Felpham in September, he could write “And Now Begins a New life. because another covering of Earth is shaken off.”Blake to Flaxman, 21 Sept. 1800 (E 710). In his letters of this period these images of ascent—of release from the pit, of resurrection, of shaking off the earth—eventually take the form of a specific and repeated biblical topos that derives from Genesis 28:

And Jacob went out from Beer-sheba, and went toward Haran. And he lighted upon a certain place, and tarried there all night, because the sun was set; and he took of the stones of that place, and put them for his pillows, and lay down in that place to sleep. And he dreamed, and behold a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven: and behold the angels of God ascending and descending on it. And, behold, the LORD stood above it, and said, I am the LORD God of Abraham thy father, and the God of Isaac: the land whereon thou liest, to thee will I give it, and to thy seed; and thy seed shall be as the dust of the earth, and thou shalt spread abroad to the west, and to the east, and to the north, and to the south: and in thee and in thy seed shall all the families of the earth be blessed. And, behold, I am with thee, and will keep thee in all places whither thou goest, and will bring thee again into this land; for I will not leave thee, until I have done that which I have spoken to thee of. And Jacob awaked out of his sleep, and he said, Surely the LORD is in this place; and I knew it not. And he was afraid, and said, How dreadful is this place! this is none other but the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven. (Genesis 28.10-17)This passage shares with the visions discussed earlier (of Ezekiel, Paul, John, and of Blake himself) the possibility of ascent into heaven and of encounter with the divine. The passage also narrates Jacob’s exile and wandering, and the establishment of a new covenant between him and God, which Blake appropriates to conceptualize his own changed circumstances as he moves from the political and religious ferment of 1790s London to beginning a new century in this quiet, south-coast seaside village.For Blake’s visceral response to contemporary London, see the letter to Cumberland, 1 Sept. 1800 (Bentley, Blake Records 95-97). This new covenant characterizes Blake’s new life in his reestablished connections with God, with friendships, and with artistic inspiration.

In the correspondence of this period Blake clearly envisages Jacob’s ladder as beginning in heaven and descending in a spiral over Felpham, winding around the Turret (his new place of work) to arrive at his own cottage door. In verses enclosed in a letter to Anna Flaxman, he writes:

Away to Sweet Felpham for Heaven is thereBlake’s mention of his “Brother” could refer to Hayley,Hayley is, presumably, the “blessd Hermit” of the penultimate line. but in this inspirational context, with angels ascending and descending from heaven, it seems more likely to refer to his dead brother Robert, with whom Blake continues to “converse daily & hourly in the Spirit.”Blake to Hayley, 6 May 1800 (E 705). The imagery of the new covenant is emphasized through the bread and wine elements of the Last Supper,Matthew 26.26-29; Mark 14.22-25; Luke 22.13-20. and the “seventy seven” flights of steps perhaps correspond to the forgiveness of sins that Blake considers central to Christianity.“Then came Peter to him, and said, Lord, how oft shall my brother sin against me, and I forgive him? till seven times? Jesus saith unto him, I say not unto thee, Until seven times: but, Until seventy times seven” (Matthew 18.21-22); Blake: “Forgiveness of Sins This alone is the Gospel & this is the Life & Immortality brought to light by Jesus” (E 875). The “precious stones” may relate to the stones of Genesis 28.11, while the “house of God” and the “gate of heaven” of Genesis 28.17 are likewise, Blake suggests, to be found in Felpham itself:

The Ladder of Angels descends thro the air

On the Turret its spiral does softly descend

Thro’ the village then winds at My Cot i[t] does end

You stand in the village & look up to heaven

The precious stones glitter on flights seventy seven

And My Brother is there & My Friend & Thine

Descend & Ascend with the Bread & the Wine

The Bread of sweet Thought & the Wine of Delight

Feeds the Village of Felpham by day & by night

And at his own door the blessd Hermit does stand

Dispensing Unceasing to all the whole LandMrs. Blake to Mrs. Flaxman, 14 Sept. 1800 (E 709).

Felpham is a sweet place for Study. because it is more Spiritual than London Heaven opens here on all sides her golden Gates her windows are not obstructed by vapours. voices of Celestial inhabitants are more distinctly heard & their forms more distinctly seen & my Cottage is also a Shadow of their houses.Blake to Flaxman, 21 Sept. 1800 (E 710).

Blake’s particular uses of Jacob’s ladder in the correspondence of this period have a striking visual counterpart in his undated watercolor Jacob’s Ladder.He exhibited the picture as both Jacob’s Dream and Jacob’s Ladder; see Butlin 1: 338 (#438).

This continuity between Blake’s painting and his poem to Mrs. Flaxman is striking. It is more than just his painting a subject that is a presiding metaphor in his correspondence at this time: his images and letters share certain specifics that are part of neither the original Genesis narrative nor the iconographical tradition of the subject, and that do not occur together elsewhere in his corpus. Their conjugation suggests, although does not prove, that the painting may have been composed around the time of Blake’s move to Felpham.It is currently dated c. 1799-1806 by the British Museum and c. 1805 by Butlin. The continuity has been noted by Keynes, among others (Letters 21n3). What is certain is that Blake had the same imagery in his mind at the time of his relocation and at the time of the composition of the painting.In the painting, Jacob is lying on the shore of the ocean, a detail that again is not part of the biblical text or the iconographical tradition, but is relevant to Blake’s Felpham setting. The painting suggests a universality through its visual gestures to space, sky, earth, shore, and sea, indicated respectively by the stars, the clouds immediately above Jacob’s left arm and staff, the curve of the globe to the right of his foot, the rocks immediately under his right arm and side, and the waves lapping against those rocks to the bottom left of the picture (the waves resemble, for example, those in pl. 1 of Visions of the Daughters of Albion [copy O] and pl. 10 of The Marriage [copy H]). This contiguity of imagery allows us to ask what light the shared elements of Blake’s painting and the poem to Mrs. Flaxman might shed on Landscape near Felpham and “To my Friend Butts,” for the image of Jacob’s ladder has strong resonances in those works.

As I mentioned earlier, the iconographical tradition of the Jacob story typically presents the ladder as a crepuscular ray, and this is echoed in the naturalistic Landscape near Felpham, in which the rays descend from the sun to the cottage, just as the ladder “at My Cot” “does end” in the poem to Anna Flaxman. In “To my Friend Butts” there is, likewise, a great emphasis on the rays of the sun: not only the “Glorious beams” pouring from “Heavens high Streams”These “streams” in heaven may also echo the fountains and river of Revelation and Butts’s poem discussed earlier. and “the Streams / Of Heavens bright beams” that Blake stands in immediately prior to finding himself above Felpham, but also the “beams of bright gold” that enfold his limbs. The correlation to the iconographical tradition discussed above is clear: Blake’s journey with the particles of light into the sky above Felpham and into the bosom of God/Jesus is a figuration of the ascent of Jacob’s ladder among angels, who for Blake—as many of his paintings show—were beings of light.See, for example, his c. 1803-05 watercolor Angel of the Revelation. “To my Friend Butts” reconfirms numerous other elements anticipated in the letters: the transformation of Felpham into a gateway to heaven; the focus on the immediacy of firsthand experience; the glittering stones (anticipating the “particles bright”); and the vision of Blake’s “Brother” and “Friend” (in “To my Friend Butts” Blake sees his “Sister & Friend”).

This material is characterized by the coexistence and interplay of naturalistic and symbolic elements. In Blake’s Jacob’s Ladder, a painting rich in symbolism, we might expect to find “the Lord” standing above the top of the ladder as the text states (Genesis 28.13), but instead we find a comparatively naturalistic sun (from which rays emanate, but they do not form the staircase); in Landscape near Felpham, the rays of sunshine that fall on Blake’s cottage may be naturalistic, but, as Lister notes, they also seem to serve a symbolic function.Lister (pl. 25) suggests that the “sunbeam” is “perhaps meant to denote the light of inspiration shining on his home.” Again, in “To my Friend Butts” the richly symbolic narrative of Blake’s ascent into the bosom of God/Jesus to be purged of the “mire” and the “clay” resonates with the language of baptism, resurrection, and transfiguration. Yet it can also be read as a naturalistic account of a man sitting on the beach enjoying the wonderful sensation of basking in sunshine. Neither reading negates the other, as this body of work is monistic: it is simultaneously earthly and heavenly, and there is no dividing line between naturalistic and symbolic content, or between material and spiritual elements.

This continuity is still more fully realized in Milton, the prophetic poem that reaches its climax with Blake’s vision of Milton in his cottage garden at Felpham. The vision is complicated, so I will first recap some of its key (bewildering) events. Blake is in his garden when Ololon (approximately Milton’s emanation) descends in the form of “a Virgin of twelve years” and speaks to him (36.17, E 137). Milton’s Shadow also descends, though his form is rather more complex, as he is the Covering Cherub, appearing as “the Wicker Man of Scandinavia” (37.11, E 137). He is large and contains multitudes: inside him is Satan, and inside Satan is Rahab. Also inside him are the “Monstrous Churches of Beulah” and “the Gods of Ulro dark” (37.16, E 137), yet he nonetheless appears as the Puritan of tradition, dressed in black (38.8, E 138). While this is happening, the Spectre of Satan is roaring on the sea “upon mild Felpham shore” (38.13, E 139) and rolling his thunders against Milton. Rather than describing Satan from the vantage point of his cottage garden, Blake enters into Satan’s bosom (38.15, E 139), and from there shows Satan as a “ruind building of God not made with hands” (38.16, E 139) where Mystery Babylon dwells and where Jerusalem is bound in chains. Milton now addresses Satan, announcing that he (Milton) is come in self-annihilation, an act that will simultaneously annihilate Satan. Satan counters aggressively with the claim that he himself is “God the judge of all,” and that Milton must fall down and worship him (39.51-53, E 139).

Events now intensify. The “Starry Seven” are burning on Blake’s path, making it “a solid fire, as bright / As the clear Sun” as “Milton silent” comes down upon it (39.3-5, E 140). Calling on Albion to awake, “Forms / Human” go forth from the limbs of the Starry Seven, forming a “mighty Column of Fire / Surrounding Felphams Vale, reaching to the Mundane Shell” (39.8-10, E 140). Meanwhile, Satan is “Howling in his Spectre” (39.18, E 140), and in this final stage of the confrontation with Milton extends his claim to divinity by appearing in the likeness of God, surrounded by inversions of the four beasts or ZoasSee, for example, Ezekiel chapter 1 and Revelation chapter 4. (Satan’s are Chaos, Sin, Death, and Ancient Night [39.22-30, E 140]). Albion hears the call of the Starry Seven, but has not the strength to respond. Seeing in Satan his own “embodied Spectre” he tries to “walk into the Deep” at Felpham (his left foot is on the nearby “Rocks of Bognor”), but his strength fails and “with dreadful groans” he sinks back onto his couch (39.46-51, E 141).

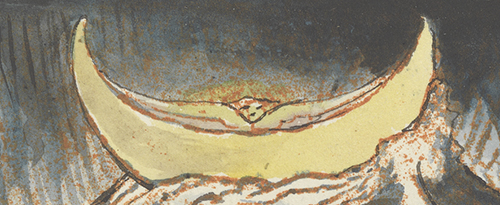

Ololon speaks conciliatory words to Milton, confessing her own part in creating a destructive natural religion (Rahab), and immediately Rahab Babylon herself appears in Satan’s bosom (40.17-20, E 141). Milton replies to Ololon that he has come in self-annihilation and to renounce the “Selfhood, which must be put off & annihilated alway / To cleanse the Face of my Spirit by Self-examination” (40.36-37, E 142). His sixfold emanations (in one sense the wives and daughters he was alienated from during his earthly life)“Those three females whom his Wives, & those three whom his Daughters / Had represented and containd” (17.1-2, E 110). now separate from Ololon and reenter Milton’s Shadow, thereby rehumanizing him (42.3-6, E 143). The Starry Seven of earlier in the scene have now become a “Starry Eight” through the reintegration of Milton. Ololon as “a Moony Ark” descends “to Felphams Vale,” while the Starry Eight are transfigured into “One Man Jesus the Saviour” and the “Clouds of Ololon” fold round his limbs “as a Garment dipped in blood” (42.10-12, E 143). Jesus walks forth from Felpham’s vale to enter Albion’s bosom, while Blake falls outstretched on his path (much as John of Patmos falls at Jesus’s feet in Revelation 1.17); the lark mounts with a loud trill (the moment of dawn), and among final apocalyptic images, the poem ends (42.19-20, 25, 29, E 143).

Like the works discussed earlier, Milton consistently expresses continuities between the naturalistic and symbolic and the material and spiritual, not least through its characters, who are (among other things) both psychic forces and natural phenomena: Los appears as the sun,In Blake’s second letter to Butts of 22 November 1802, mentioned above, the verses include a description of Los as the sun: “Then Los appeard in all his power / In the Sun he appeard descending before / My face in fierce flames in my double sight / Twas outward a Sun: inward Los in his might” (E 722). In Milton there is a corresponding passage: “Los descended to me: / And Los behind me stood; a terrible flaming Sun: just close / Behind my back; I turned round in terror, and behold. / Los stood in that fierce glowing fire” (22 [24].5-8, E 116-17). This bears a resemblance to the union with the “One Man” of “To my Friend Butts,” and perhaps explains why Sloss and Wallis identify this figure as Los (see note 31, above). Ololon as the moon (42.7, E 143), Milton as lightning (20.26, E 114), as a cloud (21.36, E 116), and so on. Yet there is a still closer association to the earlier Felpham material, again centered on the topos of Jacob’s ladder. The connection is brought to light by the phrase “paved work,” which occurs three times in Milton’s climactic scene (38.6, E 138; 39.24, E 140; 40.18, E 141). What is this “paved work”? Behind the vision of Satan stands a biblical vision of the lawgiver God of Exodus. Exodus 24.10 states that the Israelites “saw the God of Israel: and there was under his feet as it were a paved work of a sapphire stone, and as it were the body of heaven in his clearness.”God promises the “tables of stone, and a law, and commandments which I have written” to Moses just two verses later (Exodus 24.12). The image of Satan “Coming in a Cloud with Trumpets & with Fiery Flame” (39.23, E 140) points us to neighboring passages such as Exodus 19.16-20. Blake (like many interpreters) takes the clear blue “paved work” as the sky itself. Milton “descend[s]” on this paved work, and it offers a passage between heaven and earth in the same manner as Jacob’s ladder:

Milton collecting all his fibres into impregnable strengthHere the “Paved work” corresponds to the night sky, and the “precious stones” are the stars, something we have seen before in the letter to Mrs. Flaxman, where the “precious stones” glitter on the “flights” of steps.In book 1 of Milton, Satan turns the translucent “paved terraces” of his interior into the blackness of space as he shuts out the divine vision:

Descended down a Paved work of all kinds of precious stones

Out from the eastern sky; descending down into my Cottage

Garden: clothed in black, severe & silent he descended. (38.5-8, E 138)

Thus Satan rag’d amidst the Assembly! and his bosom grew

Opake against the Divine Vision: the paved terraces of

His bosom inwards shone with fires, but the stones becoming opake!

Hid him from sight, in an extreme blackness and darkness,

And there a World of deeper Ulro was open’d, in the midst

Of the Assembly. In Satans bosom a vast unfathomable Abyss. (9.30-35, E 103) The stars are also depicted in Blake’s painting of Jacob’s ladder surrounding the lower flights of the stairs, and in two of the major Milton images (pls. 29 and 33) we see stars about to enter the feet of Blake and his brother Robert, who stand next to what looks like—as Erdman points out—“the lower steps of Jacob’s ladder in Blake’s watercolor.”“We see that the stones of Satan’s paved terraces that had grown opaque have in an instant recovered their original glory as a luminous hewn-stone ladder of returning and going forth. They may properly remind us of the lower steps of Jacob’s ladder in Blake’s watercolor” (Erdman, “The Steps” 82).

Satan too stands on this “bright Paved-work / Of precious stones,” again in darkness:

Loud Satan thunderd, loud & dark upon mild Felphams ShoreThe paved work of Exodus also appears as the sky of day, as we see in its final iteration when Rahab-Babylon appears as the sun in the east:

Coming in a Cloud with Trumpets & with Fiery Flame

An awful Form eastward from midst of a bright Paved-work

Of precious stones by Cherubim surrounded: so permitted

(Lest he should fall apart in his Eternal Death) to imitate

The Eternal Great Humanity Divine surrounded by

His Cherubim & Seraphim in ever happy Eternity

Beneath sat Chaos: Sin on his right hand Death on his left

And Ancient Night spread over all the heavn his Mantle of Laws. (39.22-30, E 140)

Rahab Babylon appeardIn Milton then, the “paved work” corresponds to the skies of both day and night, and this too is consistent with Blake’s watercolor of Jacob’s ladder, in the lower half of which it is night and stars shine, while in the upper half the sun blazes its glorious rays.The similarity of the “paved work” to the ladder of Blake’s picture does not extend to its taking a spiral form, yet Milton is nonetheless full of spiral images. Los (himself the sun) has taken Blake from Lambeth to Felpham in a “whirlwind” (36.21, E 137); the flight of the lark is a spiral ascent; the “Ears in close volutions / Shot spiring out in the deep darkness” (3.17-18, E 97); and infinity is described as a “vortex” that is expressly linked to the sun, moon, and stars:

Eastward upon the Paved work across Europe & Asia

Glorious as the midday Sun in Satans bosom glowing. (40.17-19, E 141)

The nature of infinity is this: That every thing has its

Own Vortex; and when once a traveller thro Eternity.

Has passd that Vortex, he percieves it roll backward behind

His path, into a globe itself infolding; like a sun:

Or like a moon, or like a universe of starry majesty. (15.21-25, E 109)

The same luminescent passage to the heavens springs up from Blake’s garden in the climax to Milton, as the Starry Seven take on “Forms / Human” and stand “in a mighty Column of Fire” reaching from Felpham to the sky (39.8-9, E 140).The “Column of Fire” is yet another human-formed connection between heaven and earth, and also evokes the “pillar of fire” found in Exodus 13.21-22 and elsewhere. As they do so, they integrate with Milton, and thereby become “One Man Jesus the Saviour” (42.11, E 143). This column of shining human forms is strongly reminiscent of the “Heavenly Men beaming bright” who likewise appear as “One Man” who enfolds Blake in his “bosom sun bright” and makes himself known to Blake, as I suggested earlier, as Jesus. Yet what is so extraordinary about Blake’s redeployment of the Felpham vision in Milton is that he not only uses it in his vision of Jesus, but also in his vision of Satan:

The Spectre of Satan stood upon the roaring sea & beheldAs in “To my Friend Butts,” Blake sees an anthropomorphic vision over the sea at Felpham and enters into its bosom. The view from that bosom likewise opens onto sands and mountains, but they are “burning” and “terrible,” and rather than “Felpham sweet,” Blake sees “ruind palaces & cities.” This is no longer the mountain of the Lord as imagined by IsaiahSee note 33, above. and “To my Friend Butts,” but the mountain of the God of Exodus, the Hell of Paradise Lost, and the dwelling place of Babylon where Jerusalem is bound in chains. The beings of light are now “Angels & Emanations” with “blackend visages,” and the journey into the sun is not a journey into God, but into Rahab Babylon, who appears “Glorious as the midday Sun in Satans bosom glowing.”

Milton within his sleeping Humanity! trembling & shuddring

He stood upon the waves a Twenty-seven-fold mighty Demon

Gorgeous & beautiful: loud roll his thunders against Milton

Loud Satan thunderd, loud & dark upon mild Felpham shore

Not daring to touch one fibre he howld round upon the Sea.

I also stood in Satans bosom & beheld its desolations!

A ruind Man: a ruind building of God not made with hands;

Its plains of burning sand, its mountains of marble terrible:

Its pits & declivities flowing with molten ore & fountains

Of pitch & nitre: its ruind palaces & cities & mighty works;

Its furnaces of affliction in which his Angels & Emanations

Labour with blackend visages among its stupendous ruins

Arches & pyramids & porches colonades & domes:

In which dwells Mystery Babylon, here is her secret place

From hence she comes forth on the Churches in delight

Here is her Cup filld with its poisons, in these horrid vales

And here her scarlet Veil woven in pestilence & war:

Here is Jerusalem bound in chains, in the Dens of Babylon. (38.9-27, E 139)

Why do this? It seems extraordinary that rather than keeping the divine vision of “To my Friend Butts” in his heart, safe from contamination, Blake redeploys it as a vision of Satan that is so appalling, so sublime, that the reiteration is not even immediately obvious. One possibility is that he felt he had been deluded by Felpham and wished to revoke his vision,There are lines in Milton that would support this idea. The poem provides a sustained critique of “Natural Religion,” and it may be that Blake felt that he had been deceived by nature at Felpham, committing to its delights in a way that subsequently betrayed him (he was initially delighted by it, but Catherine became ill and things fell apart):

My Vegetated portion was hurried from Lambeths shades

He set me down in Felphams Vale & prepard a beautiful

Cottage for me that in three years I might write all these Visions

To display Natures cruel holiness: the deceits of Natural Religion[.] (36.22-25, E 137) but the redeployment seems to me entirely consistent with Blake’s wider work. As he never tires of showing, meaning cannot be legislated or restricted by narratives. Blake’s “infernal” readings of Paradise Lost and the book of Job in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell and of the early chapters of Genesis in The Book of Urizen offer striking examples of this. Throughout his work, he draws our attention to the fact that art provides us not with meanings, but with narrative—or imaginative—structures (such as those of Paradise Lost and the Bible) wherein meaning may be sought, contested, found, or relinquished. This applies even to his own work, such that the Felpham “Vision of Light” can be renarrated as an instance of “Single vision & Newtons sleep,” disclosing, among other things, the apocalyptic horror of an England that has come to regard reason as the only true understanding, and materialism as its core (and only) reality.

Blake develops this hermeneutic through his concept of fourfold vision, whereby the difference between being a haunted failure living in a dead universe and becoming an individual who has “traveld thro Perils & Darkness not unlike a Champion” to conquer and to “Go on Conquering … among the Stars of God & in the Abysses of the Accuser” is not about living in different worlds, but about seeing the same world at a more fully human level.The move from the former to the latter is enacted autobiographically in “With happiness stretchd across the hills,” the poem from the second letter to Butts of 22 November 1802, which narrates Blake’s recovery from depression to fourfold vision (E 720-22). The quotations in the text are from another letter to Butts of the same day (E 720). He suggests that our lives, our experiences, just as much as our art, are narrative structures, and that the content of those structures is not fixed. Salvation from the satanic nightmare, Blake suggests, involves ascending Jacob’s ladder, being raised to the divine-human level of vision through the incorporation and integration of the different aspects of our humanity, both individual and corporate. Hence the redemption of Milton—who has become dehumanized through his estrangement from his emanation—depends on his being restored to the fullness of his personhood. This is a familiar theme in Blake’s works, in which Albion’s redemption depends on the reintegration of his four Zoas and their emanations.