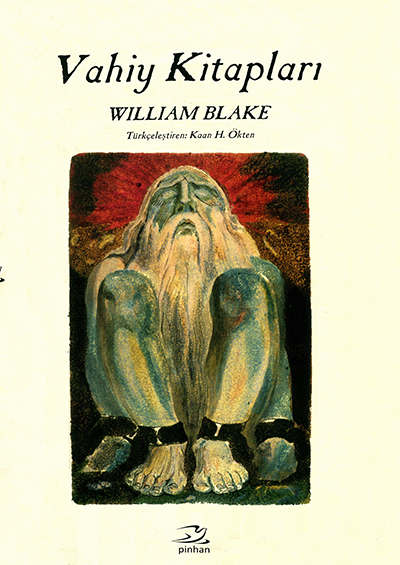

Unfortunately William Blake is not widely known in Turkey. This obscurity is partly because of his difficult symbolism. Even people adept at English find Blake challenging and incomprehensible; some relinquish the endeavor after giving it a try, but most never take it up. Even academics in Turkish literary departments tend to stay clear of Blake (with the exception of the Songs, this is true in many places, not just in Turkey); the general public is even less exposed to him. Under these circumstances, this new translation by Kaan H. Ökten (professor at Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, İstanbul) is particularly valuable, and an important stepping stone for the introduction of Blake in Turkey.

The compilation includes eight of the early illuminated prophetic works, ordered chronologically (except for The First Book of Urizen, which disrupts the chronology, as Ökten places it together with its complementary works): The Book of Thel (1789), Visions of the Daughters of Albion (1793), America a Prophecy (1793), Europe a Prophecy (1794), The Song of Los (1795), The First Book of Urizen (1794), The Book of Ahania (1795), and The Book of Los (1795).

In a concise introduction, Ökten portrays Blake as an artist and an engraver, describes the prophetic works, and sketches the significance they hold for greater understanding of Blake’s central concerns. He then explains his method of translation, in which he tries to make use of the vast expressive range of the Turkish language while keeping the epic cadence of Blake’s diction as much as possible. He finishes with a personal note about the purpose of his translation: he aims to reach those who are as interested in the Blakean perception of the universe as he is.

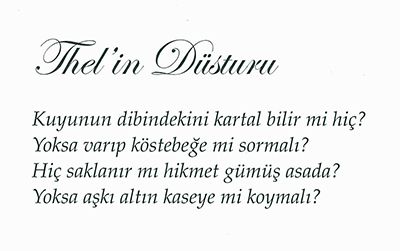

Although there have been other translations of Blake (especially of Songs and The Marriage of Heaven and Hell) by prominent figures in Turkish academia, Ökten notes that his is the first that provides facsimiles of the plates and employs his novel approach to translation. Previous translations, while trying to retain as much of the original meaning as possible, seemed bland, with a lack of Blakean sublimity. The translations of the Songs could not retain the rhythm peculiar to them because of complications caused mainly by the differences in structure and poetic conventions between the two languages. Moreover, all previous translations I have seen were text focused, without the relief-etched designs, thereby stripping the plates of their unity. Ökten’s compilation, however, is a wonderful rendition that captures Blake’s original work and passes it to the Turkish public through a mythic language that still has a certain Blakean touch. It is difficult to maintain such mythical and visionary poetic diction as Blake’s—Ökten masterfully manages to do so. The archaic words he uses in translation give the poems an air of mysticism, and he captures as well something like the rhythmic language so peculiar to Blake. Here is his version of “Thel’s Motto,” together with a phonetic rendering:

joksʌ vʌrəp kœstebeɤe: mi sormʌlə

hɪtʃ sʌklʌnər mə hɪkmet gümüʃ a:sa:dʌ

joksʌ ʌʃkə ʌltən kʌseje mi kojmʌlə/

The summaries he supplies before each work give an overall understanding of Blakean mythology even to those who have never been acquainted with it. In addition, the brief Blake glossary he presents at the end of the introduction (simplified selections from S. Foster Damon’s A Blake Dictionary) is a great help for the reader who gets lost in the intricate symbolism. Reading Blake’s poetry without the illustrations is like walking through a valley of flowers with your eyes closed; you get only a portion of the eternity he lays before you. Ökten’s compilation and translation are nearly optimal in this respect, as the left-hand pages contain the plates, and the right-hand pages the Turkish translations.