Blake’s “Holy Thursday” and

“The Martyrdom of St. Paul’s”

Clare A. Simmons (simmons.9@osu.edu) is a professor of English at the Ohio State University, Columbus, the editor of Prose Studies, and the author of Reversing the Conquest: History and Myth in Nineteenth-Century British Literature; Eyes across the Channel: French Revolutions, Party History, and British Writing 1830–1882; Popular Medievalism in Romantic-Era Britain; and papers and articles on nineteenth-century British literature and medievalism. She also edited The Clever Woman of the Family by Charlotte Mary Yonge and an essay collection, Medievalism and the Quest for the “Real” Middle Ages.

The Comic Almanack of 1838 might seem an unusual place to find a writer thinking like William Blake, but a poem for the month of June gives two views of the charity children who attended an annual service in St. Paul’s Cathedral that have some interesting similarities to those represented by Blake’s two “Holy Thursday” poems. “The Martyrdom of St. Paul’s” and its background fill out the context for Blake’s poems of innocence and experience, suggesting that he was not entirely alone in wondering whether the children involved were being exploited rather than assisted. The 1838 poem read in context helps us to see Blake’s use of the title “Holy Thursday” as a calculated choice, and thus those who suggest that at the time of writing the first poem Blake himself identified closely with his narrator’s aesthetic response to the sight may be reading overinnocently.E. D. Hirsch, for example, makes no distinction between the narrator and Blake (194-97). Most commentators, however, tend toward David V. Erdman’s description of the narrator’s “obtuse, roseate view” or Heather Glen’s account of the “benevolent observer” who receives the poet’s warning (see Erdman, Prophet against Empire 119-22, Glen 121-29). I will first outline what is known of the background to the “Holy Thursday” poems in Blake’s time, then use the poem from the Comic Almanack to understand what would have been expected of the children.

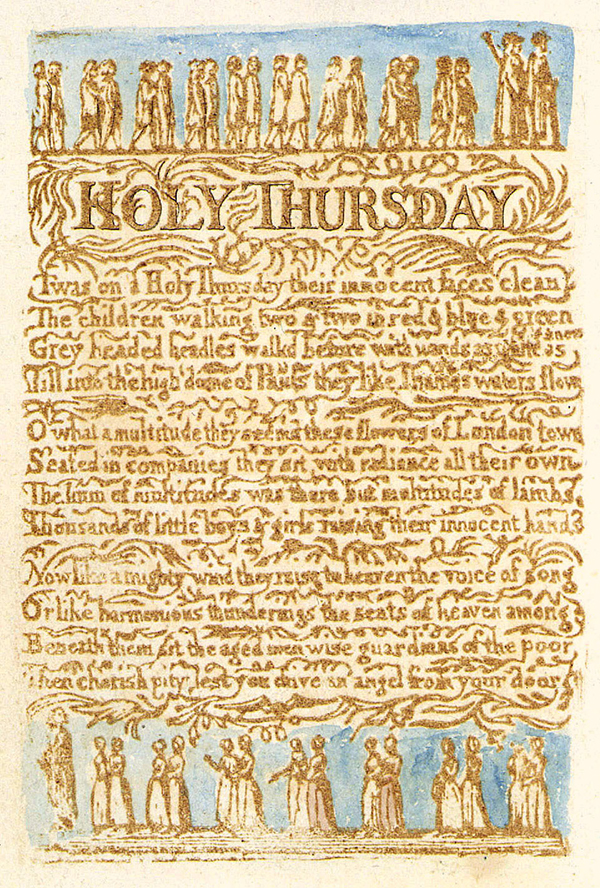

Blake’s “Holy Thursday” poems depict a ceremony in which the children of the charity schools sponsored by the London parishes participated in a church service in St. Paul’s. They are unusual among the Songs of Innocence and of Experience in drawing inspiration from an actual place and occasion. In Milton and Jerusalem Blake is very precise about locations in London and elsewhere, but even the poems from Songs that feature an actual or implied London setting—namely, “London” and “The Chimney Sweeper”—do not name identifiable places. In “Holy Thursday” from Innocence, the observer describes what he or she sees: thousands of well-washed children wearing uniforms representative of their parishes marching to St. Paul’s in pairs, and then singing movingly in the church service. They are escorted by “wise guardians of the poor,” and readers, in a phrase that reminds them of their superior social standing, are urged, “Then cherish pity, lest you drive an angel from your door.”

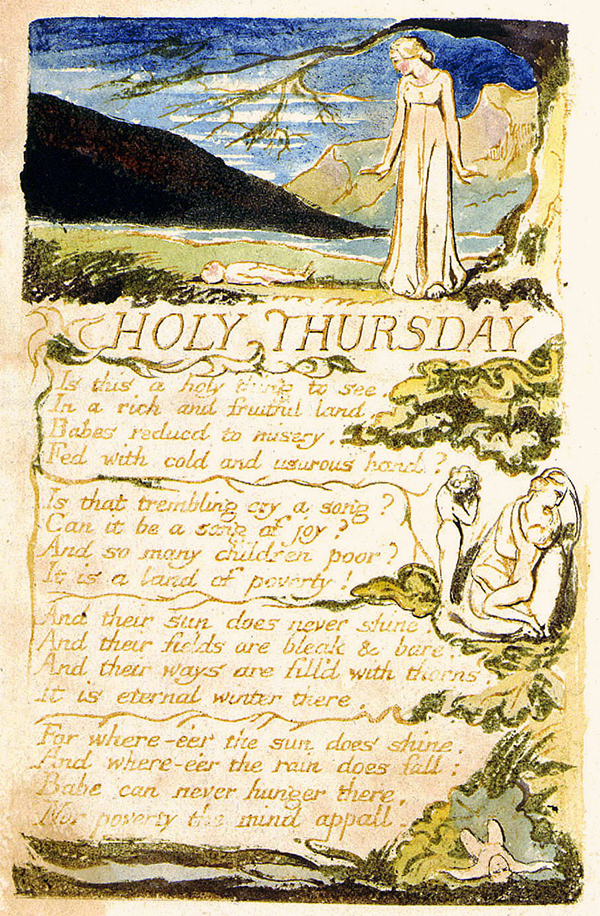

The speaker in the Experience poem is less sure of what is being observed: far from being spiritually reassured by the children’s singing, this observer detects anxiety in the form of a “trembling cry” that is quite possibly the result of coercion. This second poem does not mention the parade to St. Paul’s but apparently relies on the Innocence poem to establish the context. Whereas the speaker in Innocence observes the children marching to the cathedral and hears the performance, the speaker in Experience refers only to the assembled children, and even then questions what he or she sees. This second speaker does not conclude that the scene emphasizes national pride—if “so many children” are poor, Britain must be “a land of poverty.” If the children are to escape from “eternal winter” into a natural, nurturing world where poverty cannot “the mind appall,” the performance at St. Paul’s, which keeps them in the bonds of charity dependent on pity, is not the way to achieve it. The image shows no parade of children, but rather a harsh world in which not all children will survive.

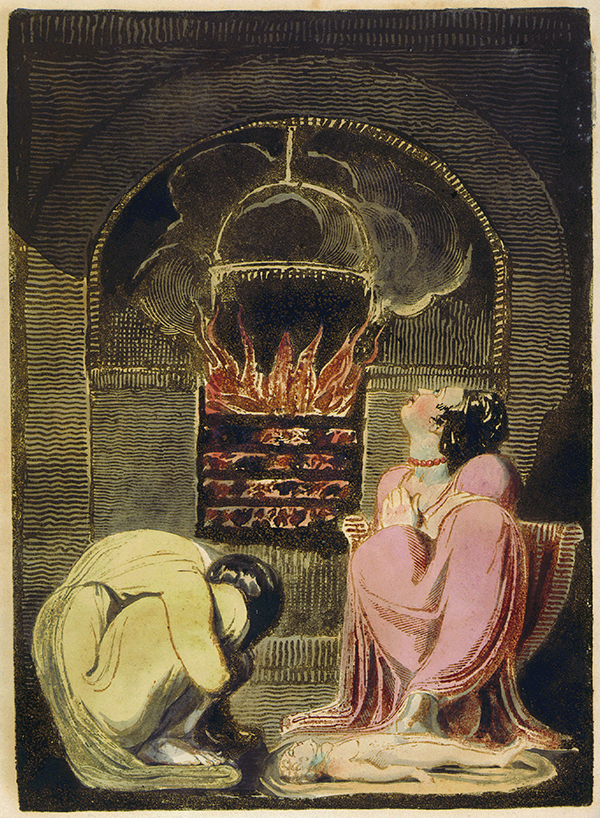

A portion of the image has a link to another of Blake’s 1794 works—and also to “The Martyrdom of St. Paul’s.” Above the Experience text a woman stands over a small child apparently dead on the ground; a similar child appears in a design from Europe that Blake’s friend George Cumberland linked to “Famine” (Erdman, Illuminated Blake 164). Commentators have associated this image of women before a pot over a roaring fire as suggestive of cannibalism brought about by the desperation of famine,See the Blake Archive illustration description for Europe copy D, object 8, at <http://www.blakearchive.org/copy/europe.d?descId=europe.d.illbk.08>. and hence as figurative of the exploitation of the poor by the rich.

The images of misery and nakedness are particularly poignant in contrast with an event associated with celebration and a distinctive form of dress. As critics have noted, the “Holy Thursday” poems are meditations on a London tradition that started soon after the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge began its patronage of charity schools in 1699.See, for example, Erdman, Prophet against Empire, Glen, and particularly the very useful article by David Fairer, “Experience Reading Innocence: Contextualizing Blake’s Holy Thursday.” The objective was to provide an Anglican education to children aged between seven and sixteen, to prepare them for useful trades (Rose 17). Each school adopted a uniform color: the boys wore jackets of this color, along with leather breeches and round caps (sometimes called thrum-caps or muffin-caps), and the girls wore long dresses of the same cloth with white aprons, broad collars, and mob-caps. Further to identify their respective schools, the boys wore a badge, usually made of pewter. The statues of a charity girl and boy at St. John of Wapping show examples of the uniform, while the inscription simultaneously reminds viewers of the importance of “voluntary contributions.”

Although the original goal of the charity schools may have been to help the indigent, by the later eighteenth century the majority of the attendees were not actually the poorest of the poor, but the sons and daughters of working families. The schools were expected to have local supporting subscribers and fundraising activities such as anniversary dinners, yet within a few years of the SPCK’s involvement organizers conceived the idea of a service bringing together children from all the London parishes to perform sacred music with the church choir as a collective charity event. Stanley Gardner is justified in noting that the charity schools were generally humane in their treatment of the children, but he ignores the pressures placed upon them as they rehearsed for and participated in the annual event (Gardner 30-37). As Fairer has pointed out, the schools were careful not to overeducate the children, the goal being to teach them Anglican Christianity and to prepare them for working life. Fairer quotes the Bishop of Norwich in 1755: “These poor children are born to be daily labourers, for the most part to earn their bread by the sweat of their brows” (543). For one day in the year, and occasionally more if there was a particular reason for a church celebration, the form of service was to perform for the wealthier classes in society, and at least in theory to gain donations for the schools.

According to M. G. Jones, the first “joint procession and service for 2000 children” took place at St. Andrew’s Church, Holborn, on 8 June 1704 (59-60). Jones quotes from the Innocence poem as an expression of “the pride and compassion aroused on these occasions” (60). At this time, St. Paul’s was still unfinished; the service moved there in 1782. The vast space of St. Paul’s was able to accommodate a reported 6000 children on tiered wooden seats under the dome. The plan was that all children from the London schools would take part; given that in 1799 the total number attending charity schools in the London area was just over 7000, almost all must have attended.Jones (60) lists the number of attendees in the late eighteenth century as 12,000; later accounts suggest that half of these were children and half audience. Many of the East London and Southwark charity schools were little more than a mile from St. Paul’s, although that would have been quite a challenge to walk with a group of thirty, forty, or even a hundred children of varying ages. Others were several miles away, however: the cathedral is three miles from Marylebone, four from Kensington, seven from Greenwich, and ten from Richmond. How the children reached the ceremony and the morning rehearsal preceding it is unclear. Possibly those from Greenwich and Richmond traveled by boat along the Thames, or perhaps they did not attend. Many children, nevertheless, must have had a long morning walk.

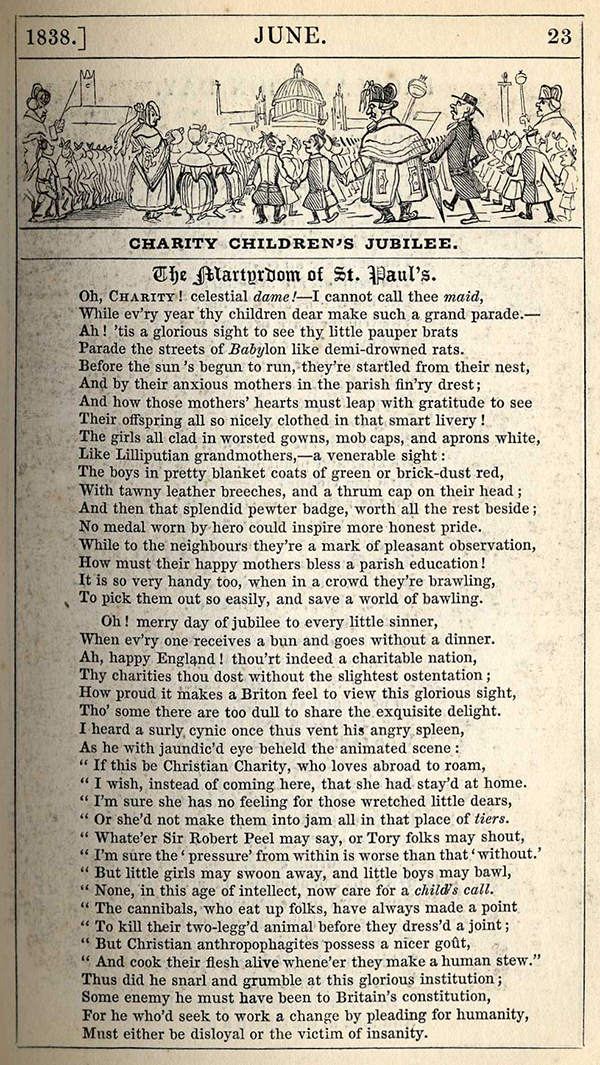

By the nineteenth century, a church service that began as a fundraiser had evolved into a concert for the wealthy so well known that the Comic Almanack marked it as a significant London event; it was to last in largely unchanged form until after the establishment of universal education in 1870. The Comic Almanack was one of many Christmas and New Year gift books printed in the 1830s. The work of Gilbert A. À Beckett, the Mayhew Brothers, William Makepeace Thackeray, and the illustrator George Cruikshank, among others, it initially purported to be an astrological almanac like Old Moore’s Almanack, but soon became more of a yearbook, with stories and features tied to the months of the year. Some gift books and annuals of this period were lavish productions, but the Comic Almanack was small and more affordable for those of modest incomes, such as tradespeople, office workers, and teachers. Like Punch in its early years, the Comic Almanack had articles and illustrations that were humorous but sometimes contained social criticism from a broadly “middle-class” perspective that assumed that its readership was neither the very rich nor the very poor. The anonymous poem “The Martyrdom of St. Paul’s” is typical in its satirical depiction of an event when the wealthy would view the poor, but those of middling incomes, who may have observed the parade but who did not have tickets to enter the building, could only watch and comment. For June 1838, the following lines appear under the titles “Charity Children’s Jubilee” and, in Gothic letters, “The Martyrdom of St. Paul’s”:

Oh, Charity! celestial dame!—I cannot call thee maid,

While ev’ry year thy children dear make such a grand parade.—

Ah! ’tis a glorious sight to see thy little pauper brats

Parade the streets of Babylon like demi-drowned rats.

Before the sun’s begun to run, they’re startled from their nest,

And by their anxious mothers in the parish fin’ry drest;

And how those mothers’ hearts must leap with gratitude to see

Their offspring all so nicely clothed in that smart livery!

The girls all clad in worsted gowns, mob caps, and aprons white,

Like Lilliputian grandmothers,—a venerable sight:

The boys in pretty blanket coats of green or brick-dust red,

With tawny leather breeches, and a thrum cap on their head;

And then that splendid pewter badge, worth all the rest beside;

No medal worn by hero could inspire more honest pride.

While to the neighbours they’re a mark of pleasant observation,

How must their happy mothers bless a parish education!

It is so very handy too, when in a crowd they’re brawling,

To pick them out so easily, and save a world of bawling.

Oh! merry day of jubilee to every little sinner,

When ev’ry one receives a bun and goes without a dinner.

Ah, happy England! thou’rt indeed a charitable nation,

Thy charities thou dost without the slightest ostentation;

How proud it makes a Briton feel to view this glorious sight,

Tho’ some there are too dull to share the exquisite delight.

I heard a surly cynic once thus vent his angry spleen,

As he with jaundic’d eye beheld the animated scene:

“If this be Christian Charity, who loves abroad to roam,

“I wish, instead of coming here, that she had stay’d at home.

“I’m sure she has no feeling for those wretched little dears,

“Or she’d not make them into jam all in that place of tiers.

“Whate’er Sir Robert Peel may say, or Tory folks may shout,

“I’m sure the ‘pressure’ from within is worse than that ‘without.’

“But little girls may swoon away, and little boys may bawl,

“None, in this age of intellect, now care for a child’s call.

“The cannibals, who eat up folks, have always made a point

“To kill their two-legg’d animal before they dress’d a joint;

“But Christian anthropophagites possess a nicer goût,

“And cook their flesh alive whene’er they make a human stew.”

Thus did he snarl and grumble at this glorious institution;

Some enemy he must have been to Britain’s constitution,

For he who’d seek to work a change by pleading for humanity,

Must either be disloyal or the victim of insanity.

These lines help supply context for Blake’s “Holy Thursday” poems in some significant respects. First, the poem answers the question as to who the children are. Even though the speaker calls them “pauper brats,” they are not orphans or from the workhouse, but have parents who have chosen to send them to school for a good education. For this ceremony—to which parents would not have been invited—their mothers have dressed them with considerable care and anxiety in their “parish fin’ry.” The children usually received new clothes for the occasion, although the garments were still in the antiquated style of the early eighteenth century: the speaker mentions the pewter badge, leather breeches, and “pretty blanket coats of green or brick-dust red.”

Second, by the position of this event in the June calendar, “The Martyrdom of St. Paul’s” suggests that the only reference to a distinctive day in the Christian year found in the Songs is not as straightforward as it initially appears. Blake’s first poem begins “Twas on a Holy Thursday,” but historically the Thursday in question was not particularly holy, and nobody but Blake seems to have named it in this way. The anniversary meeting of the charity children, as the event was more generally called, did not occur on either of the dates in the Anglican calendar known as Holy Thursday. Although both Thomas E. Connolly and Gardner noted this some decades ago, standard student textbooks are still confused on this point.

The first day traditionally described as Holy Thursday is alternatively known in England as Maundy Thursday, the day before Good Friday when Jesus washed the disciples’ feet and shared the Last Supper with them.The editors of the Norton Anthology of English Literature may be thinking of Maundy Thursday when they identify “Holy Thursday” as “a special day during the Easter season” (122). In the Church of England, as in the Roman Catholic Church, this was a day associated with charity toward the poor. Until the reign of James II the monarch distributed alms and washed the feet of doubtless carefully selected poor people; the British monarch continues to give out symbolic coins to elderly men and women on this day.For example, the Illustrated London Almanack for 1855 identifies Maundy Thursday as “the day on which the Royal bounty is distributed by the Queen’s Almoners, in the Chapel at Whitehall, to poor men and women, two for every year her Majesty has attained” (61). The tradition associates Maundy Thursday with charity, but not with the month of June (the placement of “The Martyrdom of St. Paul’s” in the Comic Almanack), since Maundy Thursday falls in March or April.

The other day often designated Holy Thursday in the Anglican calendar is the Thursday of Ascension Day, the fortieth day of Easter, and many commentators have followed Erdman in identifying Blake’s poem with Ascension Day.Erdman explains the charity-school event as taking place “every Holy Thursday (Ascension Day)” (Prophet against Empire 121); see also the Longman Anthology of British Literature (184). Duncan Wu’s Romanticism, An Anthology identifies the date as “the first Thursday in May from 1782 onwards” (192); according to Connolly’s data, 1782 was the only year in the later eighteenth century on which the service was held on the first Thursday in May (Connolly 184-85), and Ascension Day was the following Thursday. Ascension Day typically falls in May, however; it was a holy-day—that is, a holiday in the form of a day off work—for the Inns of Court, since Trinity Term began after it.Vox Stellarum, also known as Old Moore’s Almanack, published continuously since the 1700s, sometimes marks this day as Ascension Day, sometimes as Holy Thursday, and sometimes both. On Ascension Day, charity children in at least some London parishes were involved in “beating the boundaries” marking their parishes, and sometimes received a celebratory meal. William Hone’s Every-Day Book records that it is “a common custom of established usage, for the minister of each parish, with the parochial officers and other inhabitants of the parish, followed by the boys of the parish school, headed by their master, to go in procession to the different parish boundaries; which boundaries the boys strike with peeled willow wands that they bear in their hands, and this is called ‘beating the bounds’” (1: col. 652). Given the necessity of the children being in their own parishes on Ascension Day, the St. Paul’s gathering must have been held on a different Thursday.

Thursday was the usual day at St. Paul’s for special events, such as the service for the Sons of the Clergy, probably because it was well removed from Sunday, the cathedral’s busiest day of the week. The research of Fairer and others suggests that in the later eighteenth century additional parades of charity-school children were sometimes organized to celebrate days of national thanksgiving; these too were generally on Thursdays. The Thursday for the anniversary meeting was, as the Comic Almanack suggests, usually a week or more after Ascension Day, in June. Even in Blake’s time the anniversary meeting was usually celebrated on a Thursday early in June, and newspaper reports describe the event as an “annual meeting,” and sometimes as a “jubilee” or “festival,” but never as a Holy Thursday service. 1789, the year of the Songs of Innocence, was an exception, since the annual meeting was held on Thursday, 28 May, a week after Ascension Day; very possibly, the earlier date was because some scaffolding had been left in place from the day of thanksgiving on Thursday, 23 April, for the king’s recovery from illness, when the charity children had also participated (correspondents to the Times frequently complained of the inconvenience of the scaffolding erected to accommodate the children). The date of the first Thursday in June is also mentioned in Peter George Patmore’s Mirror of the Months, where the occasion is given the name of walking day; Patmore’s account gained wide circulation, since Hone reprinted it in his Every-Day Book (2: 784). Every description of the charity children mentions their clothing, and Patmore is no exception, reminding his readers that in London during the first days in June, anyone crossing the street will encounter “whole regiments of little boys in leather breeches, and little girls in white aprons, going to church to practise their annual anthem singing” (Patmore 143-44). The narrator is affected by the spectacle, noting that those who have seen and heard “the sounds of thanksgiving and adoration which they utter there [at St. Paul’s], have seen and heard what is perhaps better calculated than any thing human ever was to convey to the imagination a faint notion of what we expect to witness hereafter, when the Hosts of Heaven shall utter, with one voice, hymns of adoration before the footstool of the Most High.” The charity children may have made it difficult to cross the street, but en masse they reminded the writer of angels, just as Blake’s first speaker suggests.

By the 1830s, then, the anniversary meeting of the charity children was almost invariably scheduled for the first Thursday in June. The illustration in the Comic Almanack shows the children accompanied by wand-bearing beadles and still wearing the traditional outfits—even more out of date than they had been at the time of the “Holy Thursday” poems—and the pewter badges of the individual schools that marked them as recipients of charity. In formation, they paraded to St. Paul’s—unless their parish was further away, in which case they might have taken the horse-drawn omnibus. Under normal circumstances, charity children might have had difficulty obtaining admission to St. Paul’s, which then as now required a fee,The Times records in January 1838 a debate as to whether St. Paul’s should remain open free of charge to the general public on Sunday afternoons. In 1844, Punch pointed out that the usual admission charge of twopence was more than for many carnival sideshows (Punch 6: 84). but on this occasion they arrived in the morning in preparation for the afternoon service. They sang the Old 100th Psalm and also participated in other English church music, including Handel’s “Zadok the Priest” and the “Hallelujah Chorus,” with the St. Paul’s choir. A senior dignitary of the church gave the sermon.

Whereas other European cities had holy-days most often associated with saints, this was one of the few major parades in London. Following the service on Thursday, 4 June 1829, the Times noted it approvingly as “an exhibition exclusively English” (5 June 1829, p. 4). Word of this peculiar festival seems to have placed it on the itinerary of overseas visitors to London, since reports often mention “foreign” attendees who paid premiums for good seats and who sometimes remarked that they were deeply moved by the spectacle; these include Joseph Haydn and the czar of Russia (Jones 61; Fairer 537). Princess Victoria and her mother attended in 1836 (Allen and McClure 149). On Saturday, 3 June 1837, the Times reported the events of the previous Thursday, 1 June: On Thursday the charity children belonging to the several schools within the bills of mortalityThe area covered by the London mortality reports, by the late 1700s encompassing the cities of London and Westminster, east London, and the nearest parts of Surrey and Middlesex. visited the Cathedral church of St. Paul, attended by their rectors, beadles, masters, mistresses, and other parish functionaries, for the purpose of hearing the annual sermon which was preached by the Lord Bishop of Chichester, in the presence of the Marquis Camden, the Lord Mayor, aldermen, sheriffs, and several of the nobility and gentry. Many of the children belonging to distant parishes arrived in omnibuses, and, notwithstanding the weather in the early part of the morning was rather unfavourable, the numerous assemblage present far exceeded those of last year. Among those that occupied the scarlet seats were many foreign ladies and gentlemen, who seemed to take a lively interest in the pleasant scene presented to their view. Divine service concluded about half-past 2, after which the children proceeded to their separate schools, and were supplied with a good dinner of old English fare, plum-pudding and roast-beef. (6) This article claims that the children finally received a holiday lunch of a similar menu to Christmas, but if they had arrived early in the morning, by the time that they walked back to their parishes after 2.30 p.m., they must have been desperately hungry. Moreover, if the Comic Almanack is correct in describing their clothing as made of blanket material—worsted wool—many years they would also have been very hot.

Blake’s speakers implicitly have obtained entry to St. Paul’s and have heard the children singing. By the Victorian period, tickets were hard to obtain and advertisements in the Times announced them for sale weeks in advance. Detailed descriptions of the event, like those in the court circular in the Times, enabled middle-income readers to know what the rich were doing. For example, on Friday, 7 June 1839, the newspaper provided an account of the anniversary meeting that had taken place the previous day: The meeting was perhaps more numerous than on any former occasion. At an early hour the various groups of children and the numerous visitors began to arrive, and before 12 o’clock every seat in the Cathedral was occupied. There were nearly 6,000 children from the various charity schools, and not many less than 6,000 or 8,000 visitors, including the Lord Mayor and the civic authorities, several of the bishops, the clergy of the Cathedral, and a great number of dignitaries and other ecclesiastical persons. On the outside of the Cathedral a great mob was collected to view the procession of the children; and in the inside, the whole extent of the nave of the building, from the great western doorway to the choir, was one mass of human beings, arranged on seats one above the other to a considerable elevation from the pavement of the edifice: there appeared to us to be about 17 or 18 tiers of seats. Having made a clear distinction between the “dignitaries” inside the cathedral and the “mob” outside, the reporter goes on: The whole effect was grand and animating, and, as connected with national feelings, and the established religion of the realm, imposing and cheering. The service commenced with the singing of the 100th Psalm, “All people that on earth do dwell.” The grandeur of the effect produced by the union of so many thousand voices must be almost inconceivable to those who have not heard it. The immense mass of sound, if such a term may be allowed, was sublime. (6) The service netted a charitable offering of £646.4s., around two shillings a child without accounting for expenses. Two shillings would, of course, buy much more than a tenth of a pound would today, but would not have been enough to fund teachers even if the class size was large. Many charity schools were therefore even more dependent on other fundraisers, such as annual dinners, to support their programs.

On Friday, 5 June 1846, the Times reported on the anniversary meeting from the previous day; this year, the precise number of children was recorded—not 6000 as claimed in other years, but 2053 boys and 2017 girls.The large number of children in attendance seems to have become legendary. In Thackeray’s “Snobs of England” series—later to become The Book of Snobs—in Punch in 1846 a mention is made of “ten thousand red-cheeked charity-children in Saint Paul’s” (Punch 10: 115). Two possibilities arise for the drop in head count. The first is that the numbers in previous years had been overreported. The second is that by 1846, the old charity schools were in competition with the new ragged schools established by the charitable ladies and gentlemen of London to educate the poorest of the London street children.Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning, for instance, contributed Two Poems to be sold for the ragged schools fund in 1854: “A Plea for the Ragged Schools of London” and “The Twins (Give and It shall be given unto you).” Since only 300 copies were printed at sixpence each, even if all were sold at 100% profit the gross would have been only £7.10s., so presumably the ragged schools movement also had difficulties with effective fundraising. Perhaps some children who might have otherwise attended the charity schools chose to attend the new schools, without the embarrassing badges and caps and need to memorize “Zadok the Priest.” The 1846 article concedes that the continued antiquated dress of the children is controversial, but adds that the sight would at once have dissipated from the mind of the most obstinate that common prejudice which exists against the shape of charity children’s habiliments. However old-fashioned and odd they may appear separately, when grouped in masses they are positively handsome. The quaint, snow-white caps, tied up with riband, and holding inside of them so many healthy faces and sparkling eyes, were, of course, the principal attraction—then came the equally snow-white collar and apron, the smart-coloured frock, and the yellow, white, red, or black gloves to contrast. Each school had its own colours and its own effects of dress, and the impression was not produced by the girls alone, for the boys, with their substantial clothing and shining metal buttons, had their share in it also. (6) Moving on to the musical aspects of the service, the article records of the singing of the Old 100th, “Certainly the effect of their 4,000 voices was most startling. … There is something indescribably touching in the music of so many young vocalists, and the thrilling effect of it was heightened by the simple and beautiful tune which they sung.”

On 6 June 1851, the Times noted that “a large number of foreigners” had attended the service the day before, including the French composer Hector Berlioz. The children had performed the psalms to “thrilling effect,” but had less success with works such as the “Hallelujah Chorus” (8). Following the meeting on 7 June 1855, the Times feared that this might be the final year, owing to a lack of financial support (8 June 1855, p. 11). Similar comments were made in 1856: “If, from nearly 15,000 persons, only a few hundred pounds can be obtained, the amount is barely sufficient to cover the outlay attendant on the preparations. It would indeed be humiliating if in a city so wealthy and populous as this such a celebration as the annual assembly of the charity schools should be allowed to die for lack of encouragement” (Times 6 June 1856, p. 5). At least by this time, the SPCK seems to have been subsidizing the arrangements. The last years of the meeting included some disruptions in the schedule because of repair work on St. Paul’s; in 1860, the children performed only at the Crystal Palace, but for a few years following they sang both at the annual meeting at St. Paul’s in early June and in the Crystal Palace concert series in August, going down to Sydenham by train. The latter may have seemed more like a true holy-day to the children; overall, the annual meetings of the charity children must have caused a great deal of discomfort and anxiety for very little financial or educational gain to the scholars themselves. In 1868 the SPCK discontinued a subsidy of £50 toward costs, and this lack of support, plus concerns about fire regulations, led to the end of the anniversary assemblies in 1877, by which time national schools had assumed much of the function of the charity schools (Allen and McClure 150).

The title of the poem in the Comic Almanack, “The Martyrdom of St. Paul’s,” shows the author’s opinion of the spectacle. I do not know who wrote this poem, which as far as I can tell was never republished in its entirety except in later reprints of the Comic Almanack. One possibility is Gilbert Abbott À Beckett, an adept verse writer who had published the burlesque The Revolt of the Workhouse in 1834. In the poem, it is clear that the martyrdom is not of St. Paul, but a martyrdom taking place at St. Paul’s, where the charity children are martyrs to the public gaze. It is improbable, although not impossible, that the author knew about Blake’s Songs; the marquee name on the Comic Almanack was the illustrator George Cruikshank, who is likely to have known at least of Blake as an engraver.Copies of Songs were very rare until 1839, when a letterpress edition was published by Pickering without illustrations. “The Martyrdom of St. Paul’s” must have been composed no later than 1837 to ready the Comic Almanack to sell as a Christmas 1837 and New Year 1838 gift. “Holy Thursday” from Innocence was printed in its entirety in Benjamin Heath Malkin’s A Father’s Memoirs of His Child (London, 1806) as an example of “the feelings of a benevolent mind.”

An interesting similarity is that both “Holy Thursday” from Innocence and “The Martyrdom of St. Paul’s” are written in fairly loose long couplets that embody the long parade of children walking in pairs; Glen remarks of the Blake poem that they are walking “in the rhythm of the verse, marching hobbledehoy through the streets of London” (121). The choice of the long lines, relatively rare for both Blake and the Comic Almanack, seems deliberate, since the lines could be rearranged as traditional but not entirely regular four-line ballad stanzas. For example:

Oh, Charity! celestial dame!—

I cannot call thee maid,

While ev’ry year thy children dear

Make such a grand parade.—

And

Twas on a Holy Thursday

Their innocent faces clean

The children walking two & two

In red & blue & green.An Illustrated London News article of 1866 mentions the same colors as Blake: the girls had “dresses of scarlet, some of blue, some of green or more sombre tints” (48: 590). The accompanying illustration (585) reveals that the beadles had updated uniforms, the eighteenth-century tricorn hats having been replaced by top hats, but that the girls were still dressed in mob-caps and aprons.

On Blake’s plate, the long lines help reinforce the visual and mental image of the children.

Moreover, like Blake’s poems when read as a pair, “The Martyrdom of St. Paul’s” represents two different views of the scene. Both speakers, like Blake’s, address the scene from a position of social superiority—these are not their children, but the children of the working poor. The first speaker invokes a personified Charity as a “celestial dame,” rather like “Mercy Pity Peace and Love” in Blake’s “The Divine Image.” Blake might have appreciated the reference to materialistic London as a modern Babylon, although part of the purpose here is to pun on “baby.” Heartlessly describing the children as “little pauper brats” and “like demi-drowned rats,” this speaker takes pleasure in seeing the old-fashioned garments that the children are compelled to wear “like Lilliputian grandmothers.” If the wearers of antiquated mob-caps and “thrum cap[s]” are subject to “pleasant observation”—presumably bullying and teasing—by their neighbors, this speaker really does not care, since the scene can be justified as both picturesque and a source of national pride.Although in Oliver Twist the charity boy Noah Claypole is an unpleasant character, the narration reveals that he has been ridiculed by “shop-boys” in the neighborhood, who label him with “the ignominious epithets of ‘leathers’, ‘charity’, and the like” (78). He or she is even flippant about the fact that the children will miss their “dinner” (that is, school lunch) and just receive a “bun.” Even though this speaker would disagree with the view of the speaker in “Holy Thursday” from Experience, the two are at least in agreement that the children are “fed with cold and usurous hand.”

The second speaker, represented as overheard by the first, is less inspired with warm feelings about English charity. The first speaker interprets his grumbling about the “glorious institution” as unpatriotic: the “surly cynic” is “disloyal” and perhaps an “enemy” to “Britain’s constitution.” Yet, like the speaker in Blake’s Experience poem, this second speaker pays some attention to how the children might feel. Whereas the first has laughed at the children, the second invites the reader to laugh at the attitudes expressed in the first speaker’s description. In the kind of pun that the Comic Almanack writers cannot resist, even on occasions when they are being socially critical, the children are described as in “that place of tiers” (tears). Having already created a vaguely cannibalistic wordplay on jam into/into jam, the second speaker extends an image of the dinnerless children being cooked alive. Tiers of thousands of children in St. Paul’s might well have been very warm in June, causing little girls to “swoon away”: this adds an extra irony to the observation by the speaker in “Holy Thursday” from Experience that the bleakness of the treatment of the poor makes their lives an “eternal winter.” The image of cooking “their flesh alive” suggests that the children are expendable commodities; an event intended to raise money for them makes them a spectacle for the rich. The similarity in thought to the plates from Europe and Experience featuring the dead children is disturbing. Even though its tone appears to be humorous, “The Martyrdom of St. Paul’s” echoes the discomfort, if not outrage, of the Experience question, “Is this a holy thing to see[?]”

“Holy Thursday” from Experience raises the question, “Is that trembling cry a song?” Similarly, in the “Martyrdom of St. Paul’s” verses, the children are heard only collectively, not as individuals, even though this is a festival supposed to give them a voice: “None, in this age of intellect, now care for a child’s call.” The italics suggest a pun, possibly referring to the superstition that to be born partially or entirely with a caul, or amniotic membrane, was a sign of good fortune. Here it adds to the irony, since the speaker of these lines remains unsure that the children were born lucky. Blake would surely have agreed with these images of the exploitation of the poor that gave the rich the chance to be seen in public exercising pity for little financial outlay.

The wordplay in “The Martyrdom of St. Paul’s” is (call/caul excepted) obvious; that in Blake’s “Holy Thursday” poems is more subtle, to the extent that it seems to have escaped many commentators. In Blake’s poems, “Holy Thursday” is not functioning as a date in the Christian calendar, but does have multiple other meanings. First, it serves as an ironic reminder that an annual event held on a Thursday merely for the convenience of St. Paul’s and its patrons is now a substitute for true holiness and humility toward the poor that Christ showed by example on the Thursday before his death. Second, something that might appear to be the children’s holy-day (holiday) from school in the tradition of Ascension Day and the saints’ days of old has become what must have seemed to many of them a nervewracking, uncomfortable, and even humiliating public display. And finally, it gives Anglican London a loose equivalent of a “holy” religious spectacle, like saints’ days in Roman Catholic cities, in London’s most architecturally cosmopolitan building, St. Paul’s.

Works Cited

À Beckett, Gilbert Abbott, George Cruikshank, et al. Comic Almanack for 1838. London: Charles Tilt, [1837].

Allen, W. O. B., and Edmund McClure. Two Hundred Years: The History of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1698–1898. London: SPCK, 1898.

Connolly, Thomas E. “The Real ‘Holy Thursday’ of William Blake.” Blake Studies 6.2 (1975): 179-87.

Damrosch, David, et al., eds. The Longman Anthology of British Literature. Vol. 2A. 5th ed. Boston: Pearson, 2012.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. 1838. Ed. Peter Fairclough. London: Penguin, 1988.

Erdman, David V. Blake, Prophet against Empire. 1954. 3rd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977.

———. The Illuminated Blake. 1974. New York: Dover Books, 1992.

Fairer, David. “Experience Reading Innocence: Contextualizing Blake’s Holy Thursday.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 35.4 (summer 2002): 535-62.

Gardner, Stanley. Blake’s “Innocence” and “Experience” Retraced. 1986. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013.

Glen, Heather. Vision and Disenchantment: Blake’s “Songs” and Wordsworth’s “Lyrical Ballads.” Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

Greenblatt, Stephen, et al., eds. The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Vol. D. 9th ed. New York: Norton, 2012.

Hirsch, E. D. Innocence and Experience: An Introduction to Blake. 1964. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975.

Hone, William, ed. The Every-Day Book. 2 vols. London: William Tegg, 1826–27.

Jones, M. G. The Charity School Movement: A Study of Eighteenth Century Puritanism in Action. 1938. Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1964.

Malkin, Benjamin Heath. A Father’s Memoirs of His Child. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, 1806.

Patmore, P. G. Mirror of the Months. London: G. B. Whittaker, 1826.

Rose, Craig. “London’s Charity Schools, 1690–1730.” History Today 40.3 (March 1990): 17-23.

Wu, Duncan, ed. Romanticism, An Anthology. 4th ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.