Reading Jerusalem: The Horizon of Expectations

Sheila Spector (sheilaspector@verizon.net) is an independent scholar who has devoted her career to exploring the intersection between romanticism and Judaica in general, and Blake and Kabbalism in particular. In preparation for her work on Blake, she compiled Jewish Mysticism: An Annotated Bibliography on the Kabbalah in English (Garland). She then published “Glorious incomprehensible”: The Development of Blake’s Kabbalistic Language and “Wonders Divine”: The Development of Blake’s Kabbalistic Myth (both Bucknell UP). Currently, she is working on a book-length study of Blake’s evolution from an exoteric to an esoteric thinker and artist (to be published by Routledge).

Introduction

I. Purpose

II. Point of View

III. Myth

Setting

Characterization

Plot

IV. Theme

Conclusion

Despite Blake’s belief that Jerusalem fulfilled its purpose, its readers have found it puzzling, if not incomprehensible.In a letter to George Cumberland (12 April 1827), Blake says he considers Jerusalem to be “Finishd” (E 784). (All Blake citations are to the Erdman edition, abbreviated E; unless indicated otherwise, all Blake quotations are from Jerusalem.) In “Jerusalem and Blake’s Final Works,” Essick initiates twenty-first-century criticism with the observation, “To plunge into Jerusalem is to confront a profoundly unsettling experience” (251). More recently, the focus has shifted from Blake’s intention to reader’s response. In the most extensive studies, Yoder’s The Narrative Structure of William Blake’s Poem Jerusalem approaches the poem “as a combination of narrative and drama” (15), while Sklar’s Blake’s Jerusalem as Visionary Theatre interprets it as “visionary theatre” (3). Both provide good surveys of the earlier critical context (Yoder 4-21, Sklar 8-15). It should be noted that while Essick, Yoder, Sklar, and I frequently arrive at the same conclusions, our assumptions and procedures differ. This disparity between his intention and their response reflects a hermeneutical dysfunction: attempts to reconcile the conventional horizon of expectations with the prophecy have proved unsuccessful. Although the tendency has been to blame Blake for not conforming to his audience’s preconceptions, the opposite is the case: their horizon of expectations is predicated on two generally unexamined, inappropriate premises. First, despite Blake’s assertion that he created his own system, readers have consistently approached Jerusalem as though it were predicated on the conventional Western exoteric myth, which is polarized around the duality of good and evil. The second assumption is that the myth remains consistent throughout Blake’s corpus, a supposition that has led to a kind of anachronism in which interpretations of earlier works have been imposed on texts written sometimes decades later, or, conversely, in which later works have been used to back-read earlier texts. These two assumptions constitute the primary obstacles to understanding Jerusalem.

As a corrective, this paper seeks to generate an alternative horizon of expectations, predicated on an esoteric, as opposed to exoteric, approach.For purposes of clarity, I oversimplify “esoteric” to signify that which is limited to a privileged inner circle, and “exoteric” that which is designed for public consumption. For a historical overview, see Hanegraaff, “Esotericism.” von Stuckrad discusses the intellectual implications in “Conceptualizing the Study of Esoteric Discourse,” the third chapter of Locations of Knowledge in Medieval and Early Modern Europe (43-64). Finally, I follow Frye’s lead in Anatomy of Criticism (133) and merge classical and Christian archetypes into an amalgamated Western myth, which I describe with the phrase “exoteric Christian.” This is not an arbitrary choice; as I demonstrate in my companion volumes “Glorious incomprehensible”: The Development of Blake’s Kabbalistic Language and “Wonders Divine”: The Development of Blake’s Kabbalistic Myth, Blake gradually incorporated aspects of the kabbalistic attitude toward language and elements of the kabbalistic myth into his composite art, culminating in Jerusalem.The historical, cultural, and textual justifications for most of my assertions can be found in these two books. Rather than repeat myself, I include parenthetical references to indicate where more information is located, using the abbreviations GI for “Glorious incomprehensible” and WD for “Wonders Divine.” In those studies, I explored what Blake had done; here, I consider how and why he did it. Based on and designed only for Jerusalem, the following horizon of expectations is meant to provide the foundation for more coherent readings of Blake’s final prophecy.

Reduced to the basics, narrative revolves around four elements: 1) purpose; 2) point of view; 3) myth; and 4) theme. Governing all choices is purpose. Unlike conventional literature, which is said either to imitate an action or to express an emotion, the esoteric text is intended to elevate consciousness so that readers can experience vision for themselves. This alternative purpose yields an entirely new approach to point of view. As the source of the narrative, point of view is usually interpreted in terms of a consolidated ego whose knowledge, bias, and psychological state all determine how the story is told. The esoteric narrator, in contrast, situates himself as a mediating secretary, attempting to annihilate the selfhood so that he can translate the divine vision into comprehensible language, as structured by the culture’s dominating myth. In the West, exoteric Christianity provides the basis for interpreting the setting, characters, and plot sequence. Through the esoteric myth, Blake replaces the corporeal world of time and space with the fourfold kabbalistic cosmos. Characters, no longer lining up along the moral axis of good and evil, aggregate around the three main figures: Jerusalem, the eponymous heroine; Los, the macrocosm; and Albion, the microcosm. Finally, the plot conforms to the cycle of exile and return. Together, these formal elements produce an allegory articulating Jerusalem’s theme, the prisca theologia: belief that there existed a pure form of Christianity historically suppressed by the organized church. Obviously heretical, the theme helps explain why Blake felt the need for an esoteric—that is, private—as opposed to an exoteric—public—horizon of expectations.

The purpose of Jerusalem is transformative (GI 27-33, 151-63). Basic communication, though necessary, is self-limiting, implying that anything beyond its bounds is irrelevant, if not nonexistent. The fundamental flaw in empirical logic is its failure to acknowledge that the supposedly objective mode of thought is essentially subjective: “If Perceptive Organs vary: Objects of Perception seem to vary: / If the Perceptive Organs close: their Objects seem to close also” (30 [34].55-56, E 177). Basically, as Los points out, it is impossible for the physical senses to perceive anything not amenable to the physical senses. This does not mean that nothing else can exist, only that empiricism is incapable of processing anything beyond its circumscribed capabilities.

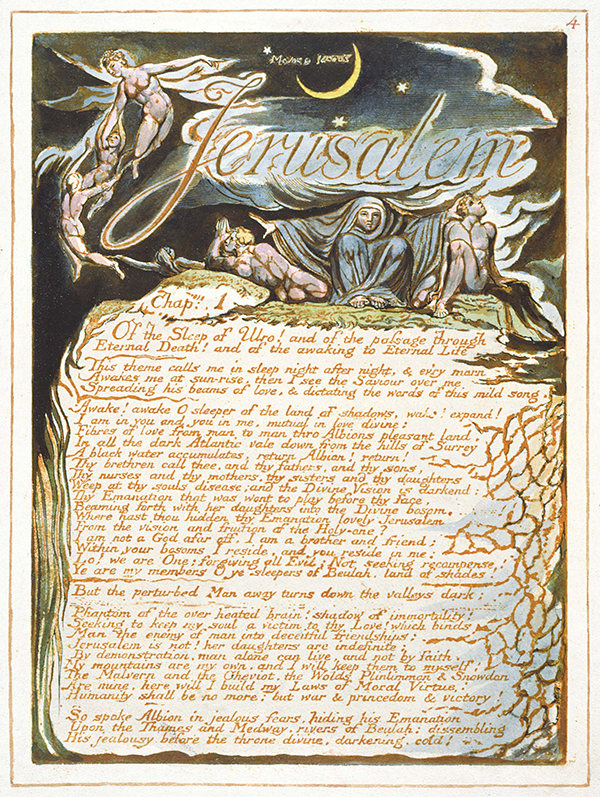

Jerusalem encourages the development of what Blake had earlier called the “Poetic Genius,” the innate gnostic extrarational faculty that apprehends spiritual realms beyond the range of empiricism.Though apparently unaware of scholarship on the subject, Sklar, in describing the “visionary theatre” (3), and Yoder, in explaining the “rhetoric of discontinuity” (The Narrative Structure 97), both approximate the transformative mode of thought. On plate 4, Albion initiates the crisis when, choosing demonstration over faith, he denies the possibility of alternative modes of knowing. The ensuing prophecy depicts how to transgress those newly imposed boundaries, by recognizing and developing the gnostic faculty, identified as “a Gate of precious stones and gold / Seen only by Emanations, by vegetations viewless” (34 [38].55-56, E 181). While it still exists—“There is a Grain of Sand in Lambeth that Satan cannot find”—that faculty has been diminished, if not obscured, by organized religion: “But should the Watch Fiends find it, they would call it Sin / And lay its Heavens & their inhabitants in blood of punishment” (37 [41].15, 19-20, E 183). Although condemned, the gnostic faculty, as Los realizes at the climax of chapter 4, endows man with the ability to apprehend higher spiritual realms: “When in Eternity Man converses with Man they enter / Into each others Bosom (which are Universes of delight)” (88.3-4, E 246). Finally, at the end of the prophecy, everyone “conversed together in Visionary forms dramatic” (98.28, E 257).Coming from an exoteric direction, Easson derives basically the same conclusion, that Blake “sacrificed those vegetable traits we call beauty for another order of beauty altogether” (327).

In order to fulfill his purpose of enabling his audience to emulate Los’s example, Blake developed a radical form of defamiliarization. More than simply presenting the ordinary in an extraordinary manner, he shatters the expected relationships among the various formal and thematic elements of narrative by substituting esoteric for exoteric archetypes. Preventing the audience from automatically processing the content, Blake encourages them, instead, to reflect on the mode of presentation, so that they can then reconnect with their own innate gnostic faculties. In this way, he accomplishes his “great task! / To open the Eternal Worlds, to open the immortal Eyes / Of Man inwards into the Worlds of Thought: into Eternity” (5.17-19, E 147).

Interpretation hinges on point of view, the consciousness through which a narrative is filtered. In the kabbalistic system, there is a hierarchy of four modes of interpretation—literal, allegorical, moral, and mystical: [Literal], the “simple” interpretation of the Scriptures, approaching it by all the ways available to elementary reasoning; [allegorical], “allusion” to the many meanings hidden in every phrase, every letter, sign and point of the Torah; [moral], the “homiletic exposition” of doctrinal truths, including all possible interpretations of the Torah; [mystical], “mystery,” initiation into … the divine wisdom concealed in the Scriptures and called, insofar as it is a teaching, … the esoteric “wisdom of the tradition.” (Schaya 18) The four levels of exegesis are manifested, in Jerusalem, by four distinct voices. The most basic, the biographical Blake, corresponds to the literal presentation of the vision. Next, the analytical voice of the prose plates provides the explanation for “every letter, sign and point” of the text. Third, the recipient of the vision (the italicized Blake) conveys the moral implication of his vision (GI 156-59). Finally, what might be called the “visualizer” coordinates between the visual and verbal to convey the esoteric “wisdom” of Jerusalem.

The poem as a whole is grounded by references to the biographical Blake, who “write[s] in South Molton Street, what I both see and hear” (34 [38].42, E 180). Like a videographer, Blake introduces references to European and Middle-Eastern geography, recent history, current events, and personal experiences in order to correlate the spiritual vision with human experience in the corporeal world.As Clark notes, “Jerusalem should be read not as the culmination of a self-enclosed mythic system, aloof from and disdainful of contemporary history, but … as a text specifically of the 1820s” (“Jerusalem as Imperial Prophecy” 181). In this way, he also exemplifies the individual who develops his gnostic faculty to apprehend higher spiritual matters. As the recipient of supernatural dictation, he encourages himself at the end of chapter 2: “Shudder not, but Write, & the hand of God will assist you! / Therefore I write” (47.17-18, E 196).

On the second level, the speaker of the prose plates explains how he has “produced a variety in every line, both of cadences & number of syllables. Every word and every letter is studied and put into its fit place” (pl. 3, E 146).See my “Kabbalistic Reading of Jerusalem’s Prose Plates.” Specifically, as prefaces, the four prose plates trace the history of religion, culminating in Blake’s version of true Christianity, the prisca theologia. The first, “To the Public,” introduces both the poem as a whole and chapter 1 in particular, placing Jerusalem within a nonsectarian Christian context: “I also hope the Reader will be with me, wholly One in Jesus our Lord, who is the God [of Fire] and Lord [of Love] to whom the Ancients look’d and saw his day afar off, with trembling & amazement” (pl. 3, E 145). Next, he appeals “To the Jews,” whom he approaches philo-Semitically, like pre-Christians who share the same values: “If Humility is Christianity; you O Jews are the true Christians” (pl. 27, E 174).Lincoln associates “To the Jews” with “the disingenuous ecumenical gestures of the evangelical mission to the Jews” (159). Third, “To the Deists” condemns natural religion for denying the visionary faculty: “But your Greek Philosophy (which is a remnant of Druidism) teaches that Man is Righteous in his Vegetated Spectre: an Opinion of fatal & accursed consequence to Man” (pl. 52, E 200). Finally, “To the Christians” advocates the true version of Christianity: “I know of no other Christianity and of no other Gospel than the liberty both of body & mind to exercise the Divine Arts of Imagination” (pl. 77, E 231).

The third level of exegesis is provided by the italicized Blake. Unlike the conventional creative consciousness, which either imitates an action or expresses an emotion, the narrator Blake assumes the role of secretary (GI 156-57):

This theme calls me in sleep night after night, & ev’ry morn

Awakes me at sun-rise, then I see the Saviour over me

Spreading his beams of love, & dictating the words of this mild song. (4.3-5, E 146)

He fulfills that function by subordinating his own ego. In praying to “Annihilate the Selfhood in me” (5.22, E 147), Blake seeks to make himself a transparent recipient of the divine vision: “So spake the Vision of Albion & in him so spake in my hearing / The Universal Father” (97.5-6, E 256).

Finally, the mystical level is provided by the visualizer, the implicit level of consciousness that coordinates the verbal and visual components into coherent image acts, the bimodal counterpart to the conventional speech act.The term image act was coined by Liza Bakewell, who argues that “images, rather than re-present reality and therefore be largely descriptive, are more accurately categorized as actions. … Furthermore, a theory of speech, together with a theory of images, must also compose a significant part of a theory of human communication: communication as action” (22). Although Bakewell does not refer to Blake, her conclusion gestures toward his composite art: “Therefore, a proper theory of speech acts should incorporate images, in the same way that a proper theory of image acts should incorporate language. These two systems of communication, as different as they are in practice, as separate and apart they often seem, are, in fact, in cahoots” (30). Unlike the conventional relationship between a verbal text and its visual illustration, in Jerusalem the mediums are complementary in the sense that each fulfills its own function, the term visualizer referring to the level of consciousness that determines which to use and how to organize their interrelationship. From this perspective, each plate can be viewed as a discrete image act, while in its totality the succession of 100 plates reflects the choices made by the visualizer as the means of conveying “the divine wisdom concealed in” Blake’s vision.

Myth provides the structuring principle for intentionality, determining the kind of relationship the mind establishes with externality (WD 19, 177n1). Thus, myth controls thought, validating and prioritizing ideas in terms of how well they conform to preexisting archetypes. In the West, the exoteric Christian myth provides the basis for most of the fundamental elements of fiction, including setting, characterization, and plot. By the time Blake worked on Jerusalem he had substituted the Christianized form of Kabbalism for the exoteric myth, to liberate himself from the preexisting system that threatened to enslave him.Adams intuits the influence of Western esotericism, inferring “some prior ur-myth,” though concluding, erroneously, “that myth never existed as such” (628).

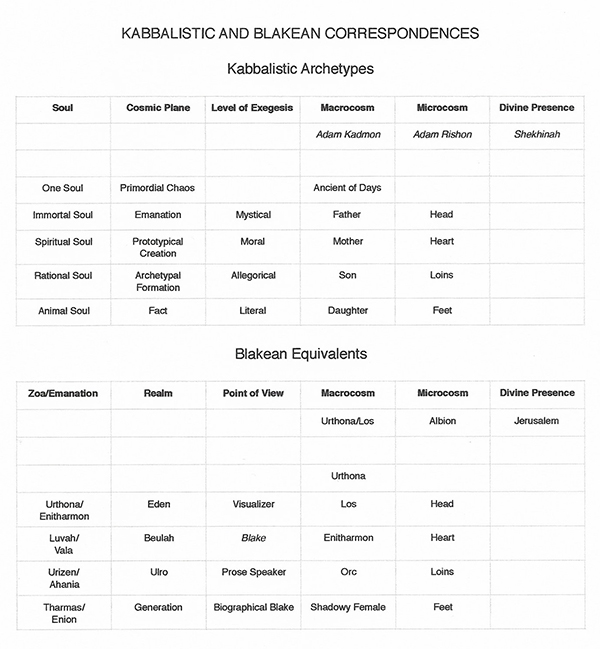

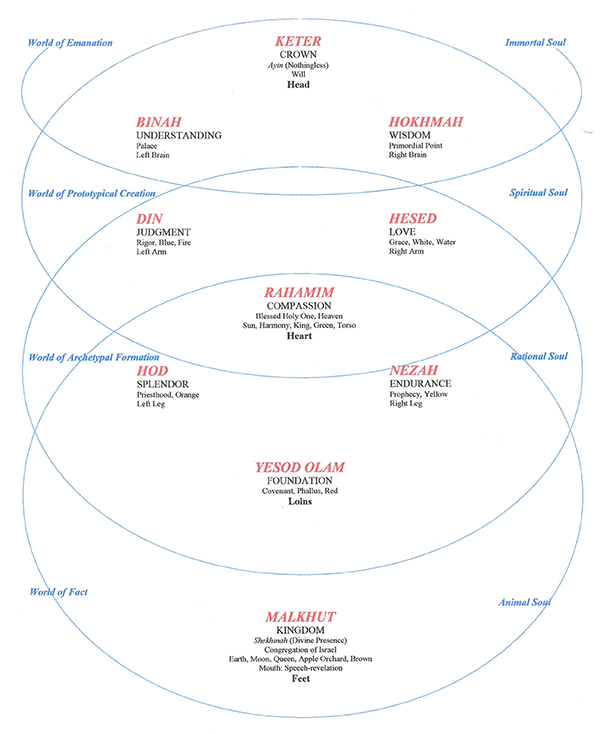

Kabbalists view our world as one of a series of cycles of existence that originated in and will revert to a primordial chaos. Temporally, Jerusalem depicts a seven-thousand-year cycle that works itself out in the first six thousand—“And all that has existed in the space of six thousand years: / Permanent, & not lost” (13.59-60, E 157)—then reverts to the state of chaos in the last thousand, in preparation for the next cycle. Spacially, the cosmos consists of four planes, governed by four souls (see illus. 1; WD 19): 1) the highest, the World of Emanation, corresponding to the godhead’s original idea to create and governed by the Immortal Soul; 2) the World of Prototypical Creation, where the idea is actualized on the spiritual plane by the Spiritual Soul; 3) the World of Archetypal Formation, where the idea is given form by the Rational Soul; and 4) the World of Fact, where the form is implemented by the Animal Soul.

All four planes were originally intended to be purely spiritual; however, the primordial error resulted in a cosmic crisis. Although the highest world remained unaffected, it became isolated from the others, which collectively became known as the World of Separation. Each of these was lowered a degree, and the last, our World of Fact, became corporeal. Now the goal is to reconnect all four.

The souls were divided in a corresponding manner, the lower three being separated from the Immortal Soul. In the now-corporeal World of Fact, the Animal Soul is tasked with providing for physical subsistence. The Rational Soul is to organize the rules by which survival can be perpetuated. On the third level, the Spiritual Soul is to analyze the process by which the rules are organized so that the three of them can reunite with the Immortal Soul and all can merge with the undifferentiated reality of the One Soul. The impediment to the process is caused by the Rational Soul, which, misperceiving itself as the height of all things, prevents, rather than facilitates, reunification. Only when reason accepts its role as passive mediator, whose function is to facilitate apprehension of higher spiritual matters, can restoration occur. Blake explores the conflict among the souls in The Four Zoas; in Jerusalem, however, they are treated collectively (see Zoas in the section on Characterization).

The setting for Jerusalem, “the Sleep of Ulro” (4.1, E 146), is the cycle initiated when Albion “turns down the valleys dark” (4.22), thereby causing the cosmic crisis: “the ancient porches of Albion are / Darken’d! they are drawn thro’ unbounded space, scatter’d upon / The Void in incoherent despair!” (5.1-3, E 147). The cycle ends when “The Breath Divine went forth over the morning hills Albion rose” (95.5, E 255). In the interim, the three lower planes remain isolated from the highest, Blake’s Eden, whose point “is walled up, till time of renovation” (12.52, E 156). Beulah, Blake’s World of Prototypical Creation, contains the actualization of the idea on the spiritual plane, as the Saviour says: “Ye are my members O ye sleepers of Beulah, land of shades!” (4.21, E 146). The third plane is “this dark Ulro & voidness” (23.38, E 169), the site where the archetypes are distorted; they are then implemented in Blake’s Generation, the arena in which regeneration can occur: “the all tremendous unfathomable Non Ens / Of Death was seen in regenerations terrific or complacent” (98.33-34, E 258). Not the penalty of Adam, corporeality is the site where—once the archetypal forms have been corrected—mortality can be transformed into immortality: “of the passage through / Eternal Death! and of the awaking to Eternal Life” (4.1-2, E 146).

Supplementing the kabbalistic myth, Los re-forms the archetypes in Golgonooza. While “Around Golgonooza lies the land of death eternal” (13.30, E 157), within the city is “A wondrous golden Building immense with ornaments sublime” (59.24, E 209). The archetype for regeneration is the Mundane Shell: “In all the Twenty-seven Heavens, numberd from Adam to Luther; / From the blue Mundane Shell, reaching to the Vegetative Earth” (13.32-33, E 157).On the significance of twenty-seven, as well as other numerological patterns, see my “Numerological Analysis of Jerusalem.” At the end of chapter 3, the form is complete:

And above Albions Land was seen the Heavenly Canaan

As the Substance is to the Shadow: and above Albions Twelve Sons

Were seen Jerusalems Sons: and all the Twelve Tribes spreading

Over Albion. As the Soul is to the Body, so Jerusalems Sons,

Are to the Sons of Albion: and Jerusalem is Albions Emanation. (71.1-5, E 224)

Finally, in chapter 4, the archetype is actualized and unity is restored: “Driving outward the Body of Death in an Eternal Death & Resurrection / Awaking it to Life among the Flowers of Beulah rejoicing in Unity” (98.20-21, E 257).

Conventionally, characters line up moralistically, as symbolic representatives of Christ and Satan. In Jerusalem, Blake denigrates this mode of thought as nothing more than “the manner of the Sons of Albion”:

in their strength

They take the Two Contraries which are calld Qualities, with which

Every Substance is clothed, they name them Good & Evil

From them they make an Abstract, which is a Negation

Not only of the Substance from which it is derived

A murderer of its own Body: but also a murderer

Of every Divine Member. (10.7-13, E 152-53)

Blake replaces this duality with an internal conflict between what the figure was intended to be and what it now appears to be: “Names anciently rememberd, but now contemn’d as fictions!” (5.38, E 148). This paradigm revolves around three main figures: Jerusalem, the eponymous heroine; Los, the macrocosm; and Albion, the microcosm. The others are either their components or manifestations on various cosmic planes. This section explains the basic archetypal identities of the figures; the significance of their interactions is indicated in the section on plot. (Bold print indicates names with their own entry.)

Jerusalem

Jerusalem is Blake’s version of the Shekhinah, the kabbalistic divine presence (WD 110, 140-41, 145). She has no active role in the myth, having gone into exile at the initial fault, to be redeemed at the end of the cycle. However, she serves as the touchstone for the action. Her initial existence indicates that there was originally to have been an immanent relationship between the creator and his creation, and her subsequent exile identifies the loss of that relationship. Albion’s rejection of the Saviour is merged with his repudiation of Jerusalem: “Jerusalem is not! her daughters are indefinite: / By demonstration, man alone can live, and not by faith” (4.27-28, E 147). The prophecy begins with Albion’s denial of Jerusalem and ends with his call for her return: “Awake! Awake Jerusalem! O lovely Emanation of Albion / Awake and overspread all Nations as in Ancient Time” (97.1-2, E 256).

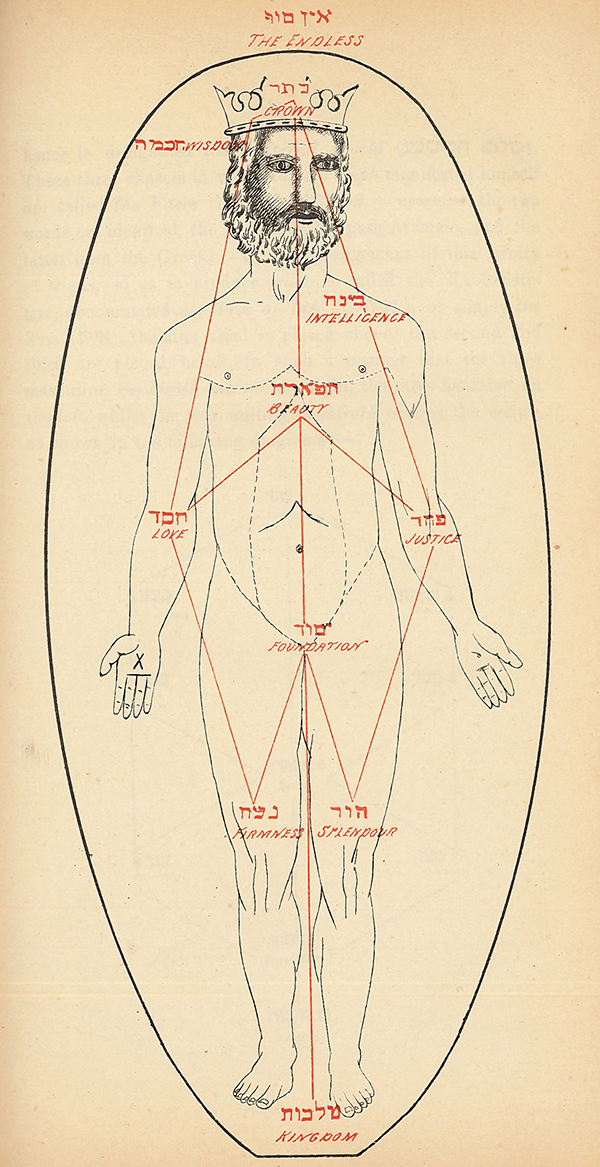

Kabbalistically, the exile of the Shekhinah is symbolized by her relationship with Adam Kadmon (primordial man), identified by Christians as the Saviour. In a radical mythic reversal, each time Adam Rishon (created man) couples with his wife, he is said to help facilitate the reunification of Adam Kadmon and the Shekhinah. Thus, the microcosm actively assists in the restoration of the macrocosm. In Jerusalem, Blake projects the reunification of the Shekhinah/Jerusalem and Adam Kadmon/Los through their ungenerated sons—Rintrah, Palamabron, Theotormon, and Bromion. Intellectualizing the myth, he does not have Adam Rishon/Albion sexually facilitate the reunification of Jerusalem and Los, but, instead, teaches him to differentiate between the shadow, Vala, and the essential reality of Jerusalem: “Vala is but thy Shadow, O thou loveliest among women! / A shadow animated by thy tears O mournful Jerusalem!” (11.24-25, E 154).

Los

Described as a manifestation of the Saviour, Los conforms to the kabbalistic Adam Kadmon, as opposed to the exoteric version of Christ (GI 159-63, WD 141-42). In the kabbalistic myth, Adam Kadmon—primordial man, the first completed entity—was intended to serve as the passive model for Adam Rishon—created or first man—to emulate. After the initial fault, Adam Kadmon was forced to assume an active role in cosmic restoration; to that end, he was fragmented into a series of physiognomies, corresponding to the souls and planes. From top to bottom, these are the Ancient of Days, the Father, the Mother, the Son, and the Daughter. The “Son,” as the active manifestation of Adam Kadmon, was the most important; not surprisingly, he was associated by Christian kabbalists with their Saviour. Mythically, the ultimate goal is the reunification of Adam Kadmon and the Shekhinah, his female counterpart.

As Adam Kadmon, Los “enterd the Door of Death for Albions sake Inspired” (1.9, E 144) and labors at his furnace to complete the archetypes of restoration. In earlier iterations of the myth, Blake had experimented with the physiognomies, associating Los with the Father, Enitharmon the Mother, Orc the “Son,” and the Shadowy Female the Daughter. However, by the time he worked on Jerusalem, he had abandoned those specific associations in favor of Los as “the Vehicular Form of strong Urthona” (53.1, E 202)—that is, the active manifestation of the Immortal Soul. At the end, Albion learns from Jesus that Los has fulfilled the true Christological function: “I see thee in the likeness & similitude of Los my Friend” (96.22, E 256).

Albion

Comparable to the biblical Adam—his name signifying the individual, the race, and the land—Albion conforms to the kabbalistic Adam Rishon, first or created man (GI 159, WD 142-45, 150). Before the initial fault, Adam is said to have been of enormous stature, extending through the four cosmic planes and containing within himself all of the souls. At the initial fault, his stature was reduced and the souls were separated from him. Some were unaffected and rose back to their source; others were contaminated and need to be purified. To that end, they undergo a series of revolutions (see Reuben), and when all are purified, the cosmos will be restored. Within this context, the biblical Adam’s disobedience is subordinated to the level of a secondary cause. Had he not eaten the forbidden fruit, the cosmos would have immediately reverted to its originally intended form; because he did, the entire cycle must be traversed.

As Adam Rishon, Albion’s initial fault is to reject the Saviour and deny the existence of Jerusalem, immanence. To compensate, he must experience the entire cycle of existence so he can differentiate between physical death and spiritual annihilation—“O that Death & Annihilation were the same!” (23.40, E 169)—and understand the true meaning of grace: self-sacrifice for the sake of others.

The other figures in the prophecy aggregate around these three. An alphabetical list of the major players follows, with brief indications of who they are and how they relate to the central conflict.

Ahania

See Emanation.

Bath

Bath is religion, a concept that, depending on the power structure, can be used either positively or negatively: “Bath who is Legions: he is the Seventh, the physician and / The poisoner: the best and worst in Heaven and Hell” (37 [41].1-2, E 183). In chapter 2, before the institutionalization of religion, Bath’s positive spiritual associations are emphasized: “Bath, mild Physician of Eternity, mysterious power / Whose springs are unsearchable & knowledg infinite” (41 [46].1-2, E 188). In chapter 3, the city is co-opted by exoteric Christianity: “They vote the death of Luvah, & they naild him to Albions Tree in Bath” (65.8, E 216). Finally, by the end of the chapter, Bath has degenerated into an instrument of natural religion: “Bath stood upon the Severn with Merlin & Bladud & Arthur / The Cup of Rahab in his hand” (75.2-3, E 230).

Bromion

See Ungenerated sons of Los and Jerusalem.

Dinah

As “the youthful form of Erin,” Dinah appears at the end of chapter 3 to foreshadow the rebirth of the female will (GI 153, WD 141, 156): “I see a Feminine Form arise from the Four terrible Zoas / Beautiful but terrible struggling to take a form of beauty” (74.52-54, E 230). Underscoring her mythic function, her name is the feminine form of Din, Hebrew for the rigorous form of judgment governing the left side of the Sefirotic Tree (see Emanation, and below under Plot).

Emanation

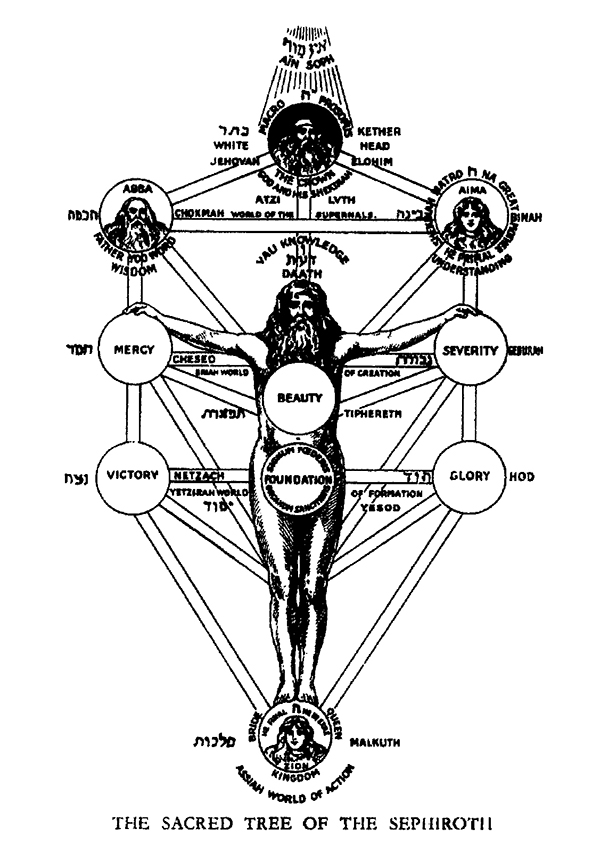

Blake’s concept of emanation is tangentially related to the kabbalistic myth, where creation is effected through a process in which the godhead is said to have emanated from himself a series of SefirotSefirah (sing.), Sefirot (pl.). To avoid confusion with Blake’s entirely different use of the term emanation, I refer to the kabbalistic emanations with their Hebrew designation.—hypostases, commonly referred to as emanations—that perform the work of creation. The Sefirot assumed a number of different configurations, the most significant being that of the Sefirotic Tree (see illus. 2-5). Horizontally, the tree corresponds to the four cosmic planes; vertically, the three columns represent the hermaphroditic split: a right side of pity, a left side of rigor, and the mediating Central Column. At the primordial fault, the sides were said to have separated, leaving each to tend toward the extreme of its nature. Now, the goal of the cosmic cycle is for the Central Column to restore balance between male and female, pity and rigor.

Iconographically, the Sefirotic Tree has been used to symbolize virtually all aspects of creation, including the macro- and microcosm, the cosmic planes, the souls, names of God, colors, planets, and body parts, to name a few (see illus. 4). While Blake does not explicitly refer to the Sefirotic Tree, beginning with the Butts tempera series he began organizing his visual art in terms of the three-columned structure.Bindman, though not knowing its source, notes the tendency: “Even so there are signs also in the Butts tempera series of distinctive compositional modes, less easily explained in terms of such outside influences. There is a tendency towards centralization in some of the paintings, which is achieved by placing the central figure firmly on the main vertical axis. … In some cases Blake goes further and relates figures on opposite sides of the picture to each other” (128). Verbally, Blake frequently uses the human correspondences of the Central Column—head, heart, loins, and feet—to signify the state of the individual. He introduces the concept on plate 14:

Los beheld his Sons, and he beheld his Daughters:

Every one a translucent Wonder: a Universe within,

Increasing inwards, into length and breadth, and heighth:

Starry & glorious: and they every one in their bright loins:

Have a beautiful golden gate which opens into the vegetative world:

And every one a gate of rubies & all sorts of precious stones

In their translucent hearts, which opens into the vegetative world:

And every one a gate of iron dreadful and wonderful,

In their translucent heads, which opens into the vegetative world.

(14.16-24, E 158; emphasis mine)

In this instance, the feet are omitted because the children are as yet ungenerated in “the vegetative world,” the World of Fact.

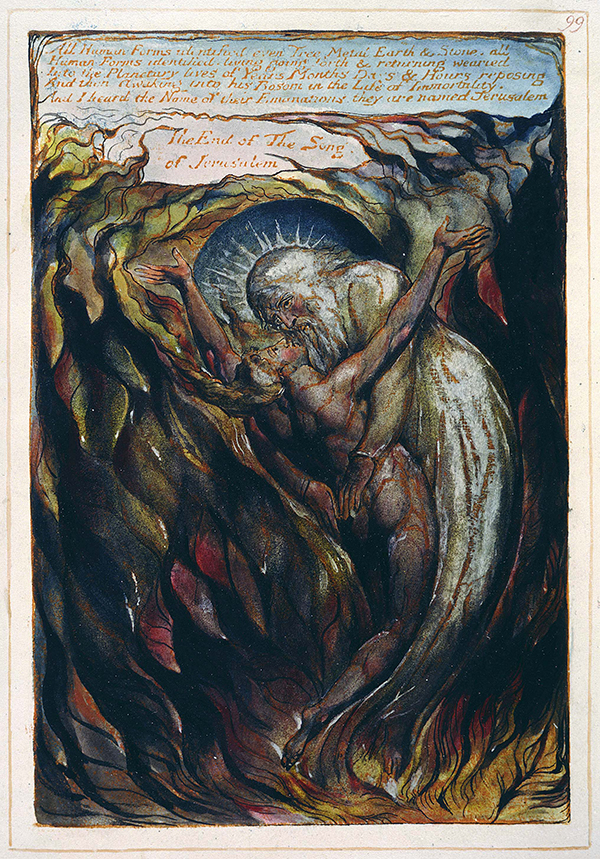

Extensions of the concept of the hermaphroditic split, Blake’s emanations are female counterparts to specific Zoas, Blake’s name for the souls (see illus. 1). Enitharmon is the emanation of Urthona, Vala of Luvah, Ahania of Urizen, and Enion of Tharmas. Only Enitharmon and Vala play significant roles in Jerusalem. Finally, as Los explains, in order for restoration to occur, “Sexes must vanish & cease / To be” (92.13-14, E 252); emanations and Zoas must merge into the Central Column, as depicted on plate 99 (see illus. 14).

The following illustrations are included to indicate the plenitude of the Sefirotic Tree as an archetypal symbol.

Enion

See Emanation.

Enitharmon

The role of Enitharmon as an emanation is complicated by her male counterpart, Los, identified as “the Vehicular Form of strong Urthona” (53.1, E 202), making him the active manifestation of Adam Kadmon. In earlier works, Blake had experimented with the kabbalistic physiognomies, making Los the Father and Enitharmon the mother (see above under Los). Although by Jerusalem he had abandoned that concept, he still retained the relationship between Los and Enitharmon, identifying her as “a vegetated mortal Wife of Los” (14.13, E 158), who labors at her loom to effect restoration. However, given the relationship between Los and Urthona, she is also the emanation of the Immortal Soul, one of “two Immortal forms” who “alone are escaped” (43 [29].28-29, E 191). They are identified as

the Emanation of Los & his

Spectre: for whereever the Emanation goes, the Spectre

Attends her as her Guard, & Los’s Emanation is named

Enitharmon, & his Spectre is named Urthona. (44 [30].1-4, E 193)

The spectre Urthona is the oxymoronic manifestation of immortality in the corporeal cosmos (see below under Spectre); in this context, Enitharmon is his female counterpart.

Erin

Expanding Erin’s signification beyond the traditional name of Ireland, Blake includes the Hebrew cognate aron, which could mean either “ark” or “tomb,” to create a symbol for the regenerated cosmos (GI 153, WD 141): “And the Spaces of Erin reach’d from the starry heighth, to the starry depth” (11.12, E 154).On the political implications of Erin, see Essick, “Erin, Ireland, and the Emanation in Blake’s Jerusalem.”

Luvah

Luvah represents the Spiritual Soul (GI 131, WD 107), being “cast into the Furnaces of affliction and sealed” (7.30, E 150). As Albion laments, “The footsteps of the Lamb of God were there: but now no more / No more shall I behold him, he is closd in Luvahs Sepulcher” (24.50-51, E 170). In chapter 3, Luvah is depicted in terms of the exoteric Christ, whose crucifixion is voted on (65.8, E 216). Allegorically, the exoteric church scapegoated spirituality for the sake of its own hegemony (see Theme, below). See also Zoas.

Palamabron

See Ungenerated sons of Los and Jerusalem.

Rahab

A Blakean construct, Rahab, whose name is based partly on the Hebrew root for breadth, signifies space in the corporeal cosmos (GI 134-36, 182n11). As daughters of Vala, whose association with Urizen consolidated a material form of religion, Rahab and Tirzah together constitute its coordinates, “weaving the deaths of the Mighty into a Tabernacle” (67.33, E 220).

Reuben

Reuben symbolizes the reincarnated soul: “Reuben slept in the Cave of Adam, and Los folded his Tongue / Between Lips of mire & clay, then sent him forth over Jordan” (32 [36].5-6, E 178) (GI 151-53, WD 149-50).

Rintrah

See Ungenerated sons of Los and Jerusalem.

Satan

In characterizing Satan, Blake exploits the Hebrew etymology of the name, “the adversary.” In exoteric Christianity, where obedience is postulated as the greatest good, its antithesis is defined as disobedience. By analogy, when the greatest good is redefined as self-annihilation, its antithesis—the consolidation of the selfhood—becomes the referent signified by the name Satan: “the Great Selfhood / Satan: Worshipd as God by the Mighty Ones of the Earth” (29 [33].17-18, E 175). As an antithetical value, Satan has no independent existence except within the framework of a binary opposition: he is a “Body of Doubt that Seems but Is Not” (93.20, E 253).

Sefirotic Tree

See Emanation.

Shadow

An adaptation of the kabbalistic ẓel, “shadow” is the projection of an inner identity (WD 110, 145):

When all their Crimes, their Punishments their Accusations of Sin:

All their Jealousies Revenges. Murders. hidings of Cruelty in Deceit

Appear only in the Outward Spheres of Visionary Space and Time. (92.15-17, E 252)

When consolidated, the inner identity becomes a spectre.

Spectre

The spectre is a Blakean adaptation of the kabbalistic ẓelem, “the principle of individuality with which every single human being is endowed, the spiritual configuration or essence that is unique to him and to him alone” (Scholem 158). In the kabbalistic myth, “the [Animal, Rational, and Spiritual Souls] were each assigned a ẓelem of their own which made it possible for them to function in the human body. Without the ẓelem the soul would burn the body up with its fierce radiance” (159). In Jerusalem, the spectres are consolidated manifestations of individual figures (WD 110, 145): “An Abstract objecting power, that Negatives every thing / This is the Spectre of Man” (10.14-15, E 153). The most important is Los’s spectre. Once consolidated, he articulates the doubts Los has about his entire enterprise, though at the end, after “Los alterd his Spectre & every Ratio of his Reason” (91.50, E 252), restoration occurs. See also Urthona.

Tharmas

Introduced as “the Vegetated Tongue even the Devouring Tongue” (14.4, E 158), Tharmas represents the Animal Soul, physical existence in the corporeal cosmos (GI 136-37, WD 108, 111): “Luvah slew Tharmas the Angel of the Tongue & Albion brought him / To Justice in his own City of Paris, denying the Resurrection” (63.5-6, E 214). See also Zoas.

Theotormon

See Ungenerated sons of Los and Jerusalem.

Tirzah

Her name deriving from the seventh commandment, lo tirzaḥ (“Thou shalt not kill”), Tirzah signifies the mortality of time: “Tirzah sits weeping to hear the shrieks of the dying: her Knife / Of flint is in her hand” (67.24-25, E 220) (GI 134-36). Together, Tirzah and her sister Rahab constitute time and space, coordinates of the corporeal cosmos, the world of Generation that will be transformed into regeneration: “Other Daughters Weave on the Cushion & Pillow, Network fine / That Rahab & Tirzah may exist & live & breathe & love” (59.42-43, E 209).

Ungenerated sons of Los and Jerusalem

A Blakean innovation, the collective use of Bromion, Theotormon, Palamabron, and Rintrah in Los is analogous to the four Zoas in Albion (WD 158). In the kabbalistic myth, the reunification of Adam Kadmon and the Shekhinah signifies cosmic restoration; in Jerusalem, the sons remain mostly ungenerated, their labor signifying the process through which restoration will be achieved: “these Four remain to guard the Four Walls of Jerusalem” (72.13, E 226).

Urizen

Urizen represents the Rational Soul, the intellectual faculty intended to organize the rules by which the Animal Soul survives (GI 131, 157).For a detailed analysis of the name Urizen, see my “The Reasons for ‘Urizen.’” In earlier works, Blake focused on the Rational Soul’s responsibility for causing the initial fault; in Jerusalem, though, Urizen actually does what he is supposed to do, “delivering Form out of confusion” (58.22, E 207). See also Zoas.

Urthona

Three mythemes converge in the figure of Urthona. The first two are kabbalistic—the Immortal Soul (GI 132) and Adam Kadmon/Los. As Los comforts himself: “I know I am Urthona keeper of the Gates of Heaven, / And that I can at will expatiate in the Gardens of bliss” (82.81-82, E 241). Finally, as the active manifestation of Urthona, Los represents the true Christological function: “the Divine Appearance was the likeness & similitude of Los” (96.7, E 255). See also Zoas.

Vala

Vala’s identity is a combination of two distinct archetypes: the emanation of Luvah and the shadow of Jerusalem (GI 138-39, 153, 183n16-17, WD 145-46). As the former, Vala is the rigorous manifestation of spirituality. At the initial conflagration, she feeds Luvah into the furnace, eliminating the merciful right side and leaving the judgmental form of religion, as manifested through two of her daughters, Rahab and Tirzah. As the shadow of Jerusalem, immanence, she is by implication transcendence. As Jerusalem reminds Vala: “The Lamb of God reciev’d me in his arms he smil’d upon us: / He made me his Bride & Wife: he gave thee to Albion” (20.39-40, E 165-66). Vala should be to Albion as Jerusalem is to the Lamb. However, the shadow has consolidated into the emanation who fed Luvah into the furnace, rejecting her intended function.

Zoas

Collectively, the four Zoas represent the four souls: Urthona, Luvah, Urizen, and Tharmas (GI 138). In the macrocosm, they govern the four cosmic planes, Eden, Beulah, Ulro, and Generation respectively. In the microcosm, they constitute the intellectual faculties whose interactions reflect Albion’s state of mind: “the Four Zoa’s who are the Four Eternal Senses of Man” (32 [36].31, E 178). Collectively, their state is used as a touchstone for evaluating Albion’s progress: in chapter 2, “the Four Zoa’s clouded rage” (32 [36].25, E 178); in chapter 3, “The Four Zoa’s rush around on all sides in dire ruin” (58.47, E 208); and immediately before Albion rises in chapter 4, “The Four Zoa’s in all their faded majesty burst out in fury / And fire” (88.55-56, E 247).

In the West, plot, organized around the conflict between good and evil, usually conforms to a linear six-part structure: exposition, conflict, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution. In contrast, the Christian kabbalistic myth, replicating the cycle of exile and return, expands the three-part Jewish prototype into four: Primordial Institution, State of Destitution, Modern Constitution, and Supreme Restitution (WD 40-46). The first phase depicts creation through a process of emanation in which the godhead produced a series of ten hypostases (for different representations, see illus. 2-5). These divine lights were placed in vessels made of dross, intended to restrain their natural effulgence. The initial fault occurred when, during the emanative process, the fifth divine light, Din (judgment), overestimating its potency, drew the other lights into its own vessel, which, proving too weak, shattered. The result was the State of Destitution. While some of the lights, remaining unaffected, were able to return to the World of Emanation, others were contaminated by the shards and drawn down to the lower worlds, with the lowest becoming corporeal. In the Modern Constitution, it is necessary to separate out the shards of dross so that the lights can return to their original locations. The process is to be accomplished through the efforts of both the macro- and microcosm. On the macrocosmic level, Adam Kadmon fragments into a series of physiognomies, the most significant being the “Son,” whose function is to perform the actual separation. On the microcosmic level, Adam Rishon is to purify the soul. Because the task cannot be completed in a single lifetime, each soul must undergo a series of revolutions. Supreme Restitution will occur when all of the shards have been separated and all of the souls purified. At that point, the cosmos will return to the primordial state, in preparation for the next cycle of existence. Christians identify Adam Kadmon as Christ, associating the final phase with the Saviour’s ultimate defeat of Satan.This is the structure found in van Helmont, Sketch of Christian Kabbalism.

Blake adapts the Christian kabbalistic archetype to structure his four-part story, each chapter depicting a particular phase of Jerusalem’s exile and return: chapter 1, the Primordial Institution, is devoted to the initial crisis; chapter 2, the State of Destitution, to the aftermath of that crisis; chapter 3, the Modern Constitution, to the compensation for the crisis; and chapter 4, Supreme Restitution, to cosmic restoration.For earlier attempts to explain the four-part structure of Jerusalem, see WD 189n30. More recently, Sklar has argued that the “characters’ overlapping stories create a tale of Albion’s fall and Jerusalem’s banishment (in Chapter One), a series of rescue attempts (in Chapter Two), a chaotic crescendo of violence and war (in Chapter Three), and finally, humanity’s great awakening in Jerusalem, a woman-city embodying forgiveness and liberty (in Chapter Four)” (145). In contrast, Yoder “offer[s] an outline of the poem … to identify the major narrative episodes and to suggest the lines of narrative continuity that unify them” (The Narrative Structure 56-57). Within each chapter, the non-linear structure is neither synchronic nor diachronic, in the causal sense.In “The Problems of Synchrony,” the first chapter of The Narrative Structure, Yoder surveys the critical controversy over whether Jerusalem is synchronic or diachronic (23-54). Rather, analogous to the relationship between Blake’s painting The Last Judgment and his Notebook description of “A Vision of the Last Judgment,” each chapter depicts a panoramic vision of a particular state, comprising a series of vignettes that constitute the vision.This process can be seen most clearly in chapter 2, where Blake shifted around the order of several vignettes. While there is no discernible causal effect, the changed order does alter the reader’s perception of the chapter. For a detailed analysis of the two sequences, see Yoder, “What Happens When.” Within that context, the plot is sequential in the sense that the four chapters depict the stages that must be experienced. As a discrete phase, each chapter is introduced emblematically by a partial-plate design, complemented by a verbal passage. At the conclusion of each, a full-plate design encapsulates the progress to that point.

Albion initiates the cycle by denying Jerusalem’s existence. The chapter opens on plate 4, with a bimodal image act in which the top third visualizes the ensuing conflict between the divine presence and her shadow (illus. 6). At the bottom of the design, Vala perverts the function of the Central Column, separating two figures. To the side, Jerusalem leads some souls through the cycle of reincarnation. The motto at the top says “Jesus only.” This is the lesson to be learned: Albion’s choice of demonstration over faith is equivalent to the exile of the Shekhinah.

From that point on, the entire cosmos is affected. On the macrocosmic level, Adam Kadmon/Los, who is fragmented into his spectre and emanation, begins to organize the spaces of Erin into the World of Separation so that he will be able to form the archetypes of restoration at his furnaces, located in Golgonooza, where he will counteract the damage done in Ulro. On the microcosmic level, Adam Rishon/Albion, having chosen demonstration over faith, can no longer apprehend the Shekhinah/Jerusalem, and erroneously embraces Vala, her shadow. The chapter ends with a prayer: “Descend O Lamb of God & take away the imputation of Sin / By the Creation of States & the deliverance of Individuals” (25.12-13, E 170). In the last five lines of the chapter, Blake calls for a complete revision of thought, in which the concept of sin is revealed to be but a component of the larger cycle of existence. By removing sin from the causal framework of action and reaction, he implies a kind of cyclical determinism, making sin but a state to be passed through.

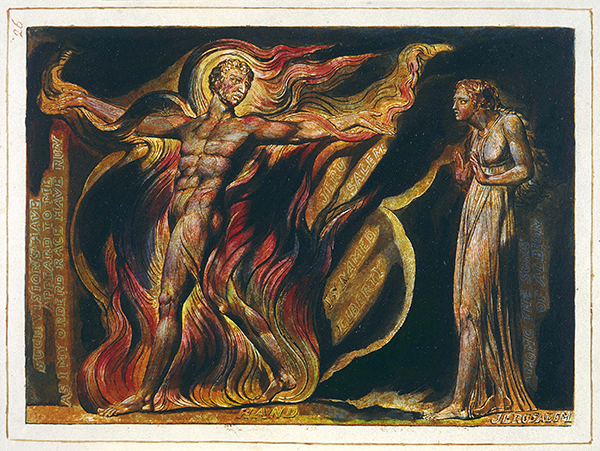

Encapsulating the plot of chapter 1, the full-page design on plate 26 (illus. 7) depicts the exile of the Shekhinah, a visual counterpart of the design on plate 4. Although the initial crisis occurred during the creation process, Adam’s sin is said to have extended the cycle. In the picture, the focal point is Hand, Albion’s eldest son, metonymically mortal man. He is engulfed in the iconography of the exoteric myth—surrounded by hell fires and with a serpent woven around his arms, which are stretched out in cruciform. Though looking back at Jerusalem, he walks away from her, thus replicating Albion’s original error of rejecting faith. He also remains oblivious to the verbal messages. Between him and Jerusalem is the notation that “JERUSALEM IS NAMED LIBERTY.” Also, looking back, he misses the motto inscribed along the left margin of the plate: “SUCH VISIONS HAVE / APPEARD TO ME / AS I MY ORDERD RACE HAVE RUN.” Visually alluding to Daniel 5, the message indicates that all is part of the succession of states—“ORDERD RACE”—to be traversed.

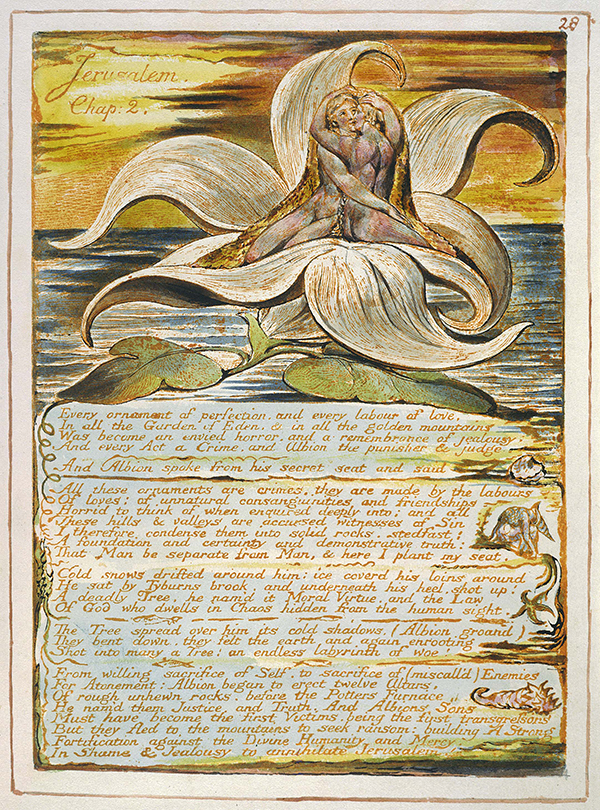

In chapter 2, corresponding to the State of Destitution, the World of Separation is consolidated simultaneously on both the macro- and microcosmic levels. Blake’s theme, the postlapsarian state of the cosmos, is depicted on plate 28 (illus. 8) by the Edenic couple embracing, followed by the verbalized perversion of that state:

Every ornament of perfection, and every labour of love,

In all the Garden of Eden, & in all the golden mountains

Was become an envied horror, and a remembrance of jealousy:

And every Act a Crime, and Albion the punisher & judge. (28.1-4, E 174)

On the microcosmic level, Adam Rishon/Albion, now in the corporeal world of time and space, becomes subject to empirical reasoning, defined as “the Great Selfhood / Satan: Worshipd as God by the Mighty Ones of the Earth” (29 [33].17-18, E 175). Albion is traduced by the superficial glamour of Vala, the shadow: “the Divine Vision / Is as nothing before thee” (29 [33].33-34, E 175). Having lost his faith, he calls for ransom: “Will none accompany me in my death? or be a Ransom for me” (35 [39].19, E 181). The result of Albion’s choice is despair: “Hope is banish’d from me” (47.18, E 196).

As the low point of the cycle, this is also the turning point of the action. On the next plate, the Saviour “Reciev’d him, in the arms of tender mercy” (48.2, E 196) and gives him the Bible (48.8-11, E 196).The list of books corresponds to those Swedenborg believed to have been divinely inspired (see Paley’s edition of Jerusalem, 207). Immediately after that, “From this sweet Place Maternal Love awoke Jerusalem” (48.18). The chapter ends with the commencement of Albion’s return, the Daughters of Beulah calling for the Lamb to “take away the remembrance of Sin” (50.30, E 200).

Plate 51 (illus. 9) balances the introduction on plate 28, where Blake depicted a prelapsarian couple embracing. Here, he visualizes Albion’s state of despair in terms of the hermaphroditic split. In the design, a male crouches with his head between his knees, as the off-center Central Column. To one side is the female emanation, sitting in defeat, and to the other is the male selfhood, in flames and enchained.Paley’s edition of Jerusalem contains discussion of an early proof that identifies the three figures as Vala, Hyle, and Skofeld (211). The elimination of the names expands the focus from the microcosm to the macrocosm. While Albion may not yet realize it, the audience has been given a visual indication that this is but a state to be passed through, and that reunification will occur.

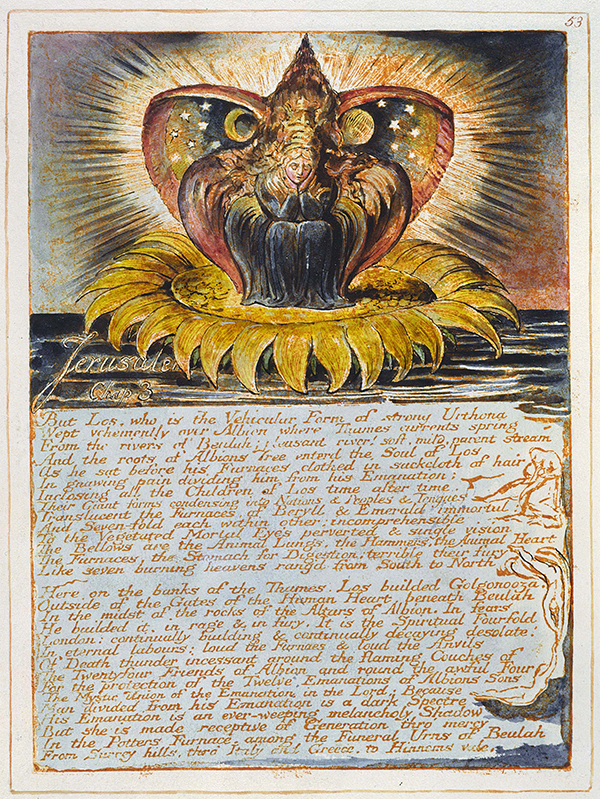

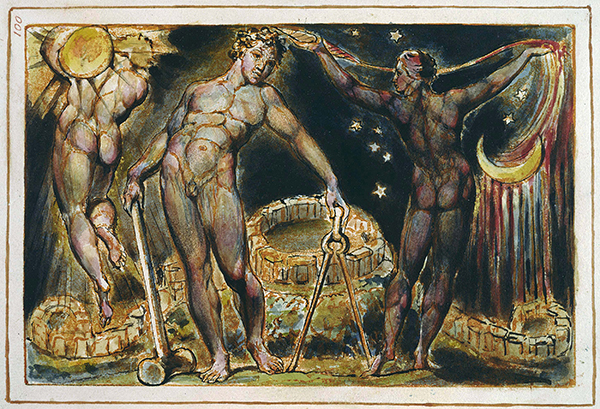

Corresponding to the Modern Constitution, in which the shards of negation are separated from the lights of purity, chapter 3 reveals the error underlying Albion’s choice of reason over faith; simultaneously, Los completes the Mundane Shell, the means by which that error will be compensated for. The theme is introduced on plate 53 (illus. 10), where the picture of Vala, surrounded by gaudy icons of organized religion, is balanced by the verbal introduction of Los as “the Vehicular Form of strong Urthona” (53.1, E 202), the manifestation of the Immortal Soul in the World of Separation. He is Adam Kadmon, the Saviour, though at this point his function is “incomprehensible / To the Vegetated Mortal Eye’s perverted & single vision” (53.10-11, E 202). Sharply differentiated from the exoteric version of Christ, who will be scapegoated on plate 65, Los builds Golgonooza, the archetype of restoration, “the Spiritual Fourfold / London” (53.18-19, E 203).

The chapter depicts human history in the corporeal cosmos, when “Albion fled beneath the Plow / Till he came to the Rock of Ages. & he took his Seat upon the Rock” (57.15-16, E 207). While Albion sits, Los constructs “The Habitation of the Spectres of the Dead & the Place / Of Redemption & of awaking again into Eternity” (59.8-9, E 208). Within that context, the exoteric myth of the crucifixion is presented in the middle of the chapter as one component of the larger divine plan: “In ignorance to view a small portion & think that All” (65.27, E 216). Luvah’s crucifixion exposes Vala as the shadow, the dark reflection of true spirituality, “weaving the deaths of the Mighty into a Tabernacle / For Rahab & Tirzah; till the Great Polypus of Generation covered the Earth” (67.33-34, E 220). Counteracting the shapeless polypus, Los forms the archetypal Mundane Shell in preparation for the consolidation of true Christianity.

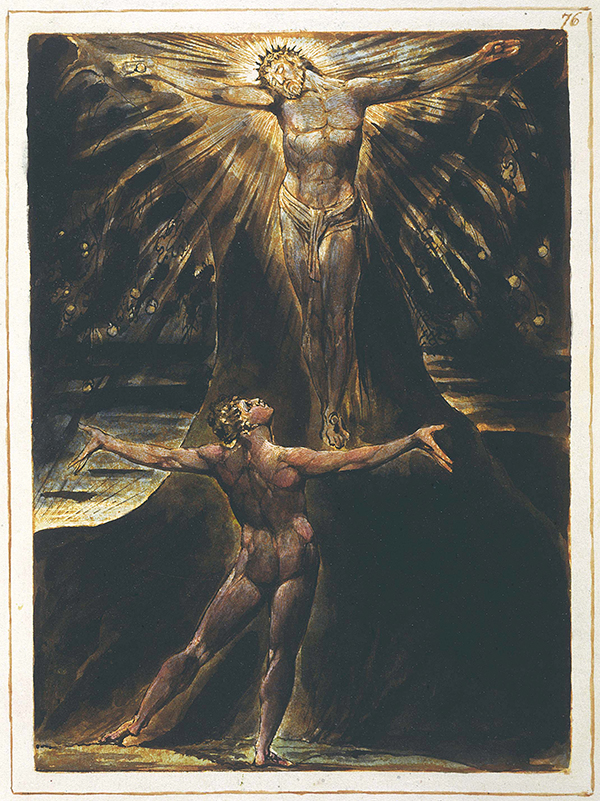

Balancing the introductory image of Vala’s religion, a full-plate depiction of true Christianity concludes the chapter: a picture of the crucified Saviour at the top, facing forward, with light emanating from his head (illus. 11). Opposite him is the human reflection, standing at the bottom, his back to the viewer, looking up at Christ. This is Adam Kadmon mirroring for Adam Rishon the true goal of separating the shards.

In contrast to the agon that concludes exoteric narrative, the esoteric resolves when the shards of negation have been removed so that the lights of purity can rise. In the final chapter, Vala’s falsehood, which threatens to obliterate Jerusalem’s truth, is exposed so that restoration, foreshadowed by the image on plate 76, can occur. The theme is introduced on plate 78 (illus. 12), with Albion sitting on the rock of ages, his bird’s head possibly a symbol of regeneration.For possible interpretations of the bird’s head, see Paley’s edition of Jerusalem, 261. The text below the design explains how Albion’s intellect will be restored: Los, as Adam Kadmon, will separate the shards, much as “the Potter breaks the potsherds” (78.5, E 233).

In the first half of the chapter, the error is consolidated so that, in the second, it can be put off. The chapter opens with a description of Jerusalem in ruins, followed by her lament over the unintended consequences of Vala’s usurpation, that right/male and left/female have not only separated from each other, but each has moved toward its own extreme: “outside appears / Thy Masculine from thy Feminine hardening against the heavens / To devour the Human!” (79.70-72, E 236). Gwendolen, representing the extreme left side, fears the loss of female power and lies: “Forgetting that Falshood is prophetic” (82.20, E 239), she claims to have “heard Enitharmon say to Los: Let the Daughters of Albion / Be scatterd abroad and let the name of Albion be forgotten” (82.22-23). She then forms the infant Hyle (whose Greek etymology means “matter”) into a material counterpart of the Lamb, intended to perpetuate her hegemony. However, as the embodiment of her lie, he grows into the anti-Christ, the consolidation of the error: “A Vegetated Christ & a Virgin Eve, are the Hermaphroditic / Blasphemy” (90.34-35, E 250). At the climax of the poem, Los puts off the error:

Thus Los alterd his Spectre & every Ratio of his Reason

He alterd time after time, with dire pain & many tears

Till he had completely divided him into a separate space. (91.50-52, E 252)

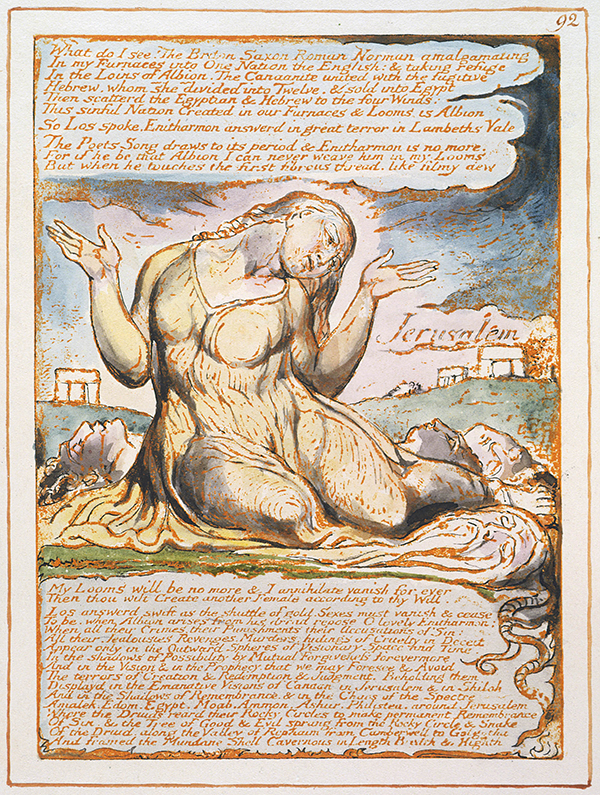

Significantly, he does not eliminate his adversary in the exoteric sense, but alters his spectre, whom he then relegates “into a separate space.” Once Los’s task of separating the shards is complete, Jerusalem can return on plate 92 (illus. 13) and Albion can rise, recognize Jesus “in the likeness & similitude of Los [his] Friend” (96.22, E 256), annihilate his selfhood, and restore the cosmos.

As this brief summary suggests, the four chapters collectively constitute a panorama of the four states of existence. Within each chapter, the action consists of a series of simultaneously coexisting bimodal image acts, each of which is designed to illuminate some aspect of that state. According to Blake, “These are States Permanently Fixed by the Divine Power” (32 [36].38, E 178). Therefore, they cannot be explained in terms of material causality; rather, “Iniquity must be imputed only / To the State [souls] are enterd into that they may be deliverd” (49.65-66, E 199). In other words, the plot traces “the passage through / Eternal Death! and … the awaking to Eternal Life” (4.1-2, E 146).

Jerusalem is an allegory whose vehicle, the esoteric kabbalistic myth, conveys the theme of the prisca theologia. Generally, prisca theologia refers to the traditional belief in an originally pure form of religion.GI 41, WD 30, 33. On the prisca theologia, see Hanegraaff, “Tradition.” Because my focus is strictly on Jerusalem, I ignore aspects of the prisca theologia not directly relevant to this paper. For the relationship of the prisca theologia to the seventeenth-century origins of freethinking, see Champion, especially chapter 5, “Prisca theologia” (133-69). In the Renaissance, the concept was Christianized to signify what adherents identified as the true form of Christianity, said to have existed in the first few centuries of the common era—between Paul and Constantine, in Blake’s twenty-seven heavens—before the organized church erased traces of its existence. What made the prisca theologia both distinct and threatening was its assertion that there exists an extrarational gnostic faculty that endows people with the ability to apprehend the spiritual realm directly, without the need for any institutional intercession. Blake apparently alludes to the prisca theologia in Milton when he refers to “an old Prophecy in Eden recorded” (20 [22].57, E 115; 23 [25].35, E 119). Then, in Jerusalem, he develops that reference, using the exile of the Shekhinah to symbolize the usurpation of true Christianity.While I agree with the first part of Kroeber’s assertion in “Delivering Jerusalem” that “the purpose of Jerusalem is to attack this foundation of institutionalized religion,” I reject the second, “which Blake represents as Druidism” (366). Blake seems as opposed to the institutionalization of Christianity as he is to any other system whose effect is to deny liberty.

Key to the allegory is the combination of Vala’s two identities: the emanation of Luvah and the shadow of Jerusalem. As an emanation, she signifies generally the left, rigorous column of the Sefirotic Tree, and as Luvah’s in particular, she embodies the judgmental component of spirituality. When, at the initial conflict, she feeds Luvah into the furnace, she eliminates the right side, mercy. The result, as seen in chapter 2, is a rationalized form of religion in which “Vala, builded by the Reasoning power in Man” (39 [44].40, E 187), forms “a pretence of Religion to destroy Religion” (38 [43].36, E 185). This is followed, in chapter 3, by the politicization of religion: “Are not Religion & Politics the Same Thing?” (57.10, E 207). In this chapter, Vala consolidates the institution by crucifying spirituality—“They vote the death of Luvah” (65.8, E 216)—to create a realm of spiritual death: “And all the Arts of Life. they changd into the Arts of Death in Albion” (65.16). The result is the oxymoronic corporealization of spirituality, when “The Twelve Daughters in Rahab & Tirzah have circumscribd the Brain / Beneath & pierced it thro the midst with a golden pin” (67.41-42, E 220). In other words, exoteric Christianity survives by lobotomizing its adherents. Finally, she degenerates into the antithesis of spirituality, intending “to destroy the Lamb & usurp the Throne of God” (78.19, E 234). Her entire system is constructed around her delusion (lie?) that “Luvah orderd me in night / To murder Albion the King of Men” (80.17-18, E 236).

The second component of Vala’s identity is the shadow. If Vala, in distorting her intended function, degenerates into a destructive, militaristic form of organized religion, then Jerusalem must be the prisca theologia, the true form of Christianity. In the beginning, Albion chooses Vala over Jerusalem, and the poem traces the disastrous consequences of that choice. At the end, when Los restores the cosmos, “Jerusalem took the Cup which foamd in Vala’s hand” (88.56, E 247). By removing the communion cup from Vala’s possession, Jerusalem restores the prisca theologia. Fittingly, this is the last reference to Vala in the prophecy, and the beginning of Jerusalem’s restoration.

Technically, readers of Jerusalem have engaged not in analysis, but in dissection, the process of breaking something down into its component parts. This can be seen most obviously in A Blake Dictionary: The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake, where Damon painstakingly describes virtually every component of the corpus. More recently, Sklar has applied the same process: “I begin by separating and dissecting Jerusalem’s components; then I discuss how they interrelate, both sequentially and holistically,” that is, “without time constraints” (4, 251). Missing has been the other constituent of analysis, the principle of structure, the organizing rationale for how the various components interrelate in terms of a unified whole.This distinction between dissection and formal analysis is clarified in Brooks and Warren: “An analysis cannot take place except in accordance with the principle of the structure of the thing being analyzed.” That principle explains “the relation among the parts” (95). Hermeneutically, this is the function of the horizon of expectations, upon which the reading process hinges. Minus a principle of structure, a text, at worst, is unintelligible, as Karen Swann describes her students’ response to Jerusalem: “The whole chapter was just mud to them” (398). Her own reception is more complex: As I returned to the text again and in subsequent years of teaching, I would often have the experience of coming across a passage that I had once seized upon as the lynchpin to a reading of the whole work but which now felt dead to the point where I couldn’t even reconstruct what I had seen in it. (And, conversely, passages I barely remembered from previous readings would leap into prominence.) (399) Swann’s protean response traces her own growth as a reader; her personal horizon of expectations was altered by exposure to other texts in the interim, between encounters with Jerusalem. As Los says, in a line quoted earlier, “If Perceptive Organs vary: Objects of Perception seem to vary.”

Swann’s example illustrates the basic assumption with which I began: there has existed no viable horizon of expectations for Jerusalem. For this reason, my intention is not to present a unique, much less definitive, interpretation. Rather, I have returned to the fundamental premises upon which the reading process is predicated, in order to configure a more consistent and appropriate horizon of expectations. I believe that the kabbalistic myth provides a viable principle of structure, and that the esoteric approach will enable future readers to generate more fruitful, provocative interpretations of Jerusalem, the book that Blake considered “Finishd.”

Works Cited

Adams, Hazard. “Jerusalem’s Didactic and Mimetic-Narrative Experiment.” Studies in Romanticism 32.4 (winter 1993): 627-54.

Bakewell, Liza. “Image Acts.” American Anthropologist 100.1 (March 1998): 22-32.

Bindman, David. Blake as an Artist. Oxford: Phaidon; New York: Dutton, 1977.

Blake, William. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. Ed. David V. Erdman. Newly rev. ed. New York: Anchor-Random House, 1988.

———. Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion. Ed. Morton D. Paley. Blake’s Illuminated Books, vol. 1. General ed. David Bindman. Princeton: William Blake Trust/Princeton UP, 1991.

Brooks, Cleanth, and Robert Penn Warren. Modern Rhetoric. Shorter 3rd ed. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972.

Champion, J. A. I. The Pillars of Priestcraft Shaken: The Church of England and Its Enemies, 1660–1730. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1992.

Clark, Steve. “Jerusalem as Imperial Prophecy.” Clark and Worrall 167-85.

Clark, Steve, and David Worrall, eds. Blake, Nation and Empire. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

Curran, Stuart, and Joseph Anthony Wittreich, Jr., eds. Blake’s Sublime Allegory: Essays on The Four Zoas, Milton, and Jerusalem. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1973.

Damon, S. Foster. A Blake Dictionary: The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake. Index by Morris Eaves. Boulder: Shambhala, 1979.

Easson, Roger R. “William Blake and His Reader in Jerusalem.” Curran and Wittreich 309-27.

Essick, Robert N. “Erin, Ireland, and the Emanation in Blake’s Jerusalem.” Clark and Worrall 201-13.

———. “Jerusalem and Blake’s Final Works.” The Cambridge Companion to William Blake. Ed. Morris Eaves. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. 251-71.

Frye, Northrop. Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1957.

Hanegraaff, Wouter J., ed. Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism. 2 vols. Leiden: Brill, 2005.

———. “Esotericism.” Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism 1: 336-40.

———. “Tradition.” Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism 2: 1125-35.

Kroeber, Karl. “Delivering Jerusalem.” Curran and Wittreich 347-67.

Lincoln, Andrew. “Restoring the Nation to Christianity: Blake and the Aftermyth of Revolution.” Clark and Worrall 153-66.

Schaya, Leo. The Universal Meaning of the Kabbalah. Trans. Nancy Pearson. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1971; Secaucus, NJ: University Books, 1972; Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1973.

Scholem, Gershom. Kabbalah. New York: Quadrangle, 1974.

Sklar, Susanne M. Blake’s Jerusalem as Visionary Theatre: Entering the Divine Body. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2011.

Spector, Sheila A. “Blake as an Eighteenth-Century Hebraist.” Blake and His Bibles. Ed. David V. Erdman. West Cornwall, CT: Locust Hill P, 1990. 179-229.

———. “Glorious incomprehensible”: The Development of Blake’s Kabbalistic Language. Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell UP, 2001.

———. Jewish Mysticism: An Annotated Bibliography on the Kabbalah in English. New York: Garland, 1984.

———. “A Kabbalistic Reading of Jerusalem’s Prose Plates.” Women Reading William Blake: “Opposition is true Friendship.” Ed. Helen P. Bruder. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. 219-27.

———. “Kabbalistic Sources—Blake’s and His Critics’.” Blake 17.3 (winter 1983–84): 84-101.

———. “A Numerological Analysis of Jerusalem.” Prophetic Character: Essays on William Blake in Honor of John E. Grant. Ed. Alexander S. Gourlay. West Cornwall, CT: Locust Hill P, 2002. 327-49.

———. “The Reasons for ‘Urizen.’” Blake 21.4 (spring 1988): 147-49.

———. “Wonders Divine”: The Development of Blake’s Kabbalistic Myth. Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell UP, 2001.

Swann, Karen. “Teaching Jerusalem.” European Romantic Review 25.3 (June 2014): 397-402.

van Helmont, Francis Mercury. Sketch of Christian Kabbalism. Trans. and ed. Sheila A. Spector. Leiden: Brill, 2012.

von Stuckrad, Kocku. Locations of Knowledge in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Leiden: Brill, 2010.

Yoder, R. Paul. The Narrative Structure of William Blake’s Poem Jerusalem: A Revisionist Interpretation. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen P, 2010.

———. “What Happens When: Narrative and the Changing Sequence of Plates in Blake’s Jerusalem, Chapter 2.” Studies in Romanticism 41.2 (summer 2002): 259-78.