A Newly Discovered Copy of Blake’s

Adam and Eve Asleep

Joseph Viscomi is the James G. Kenan Distinguished Professor of English Literature at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He is the author of Blake and the Idea of the Book and co-editor, with Robert Essick and Morris Eaves, of the William Blake Archive. His current project, Printed Paintings, examines the techniques, histories, and meanings of Blake’s large monoprints.

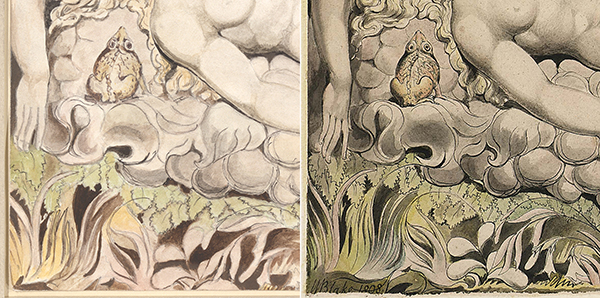

When I first saw Adam and Eve Asleep, I was excited, thinking it may be evidence that the Linnell Paradise Lost designs were not a selection of just three designs but were once part of a full set of twelve, like the Thomas and Butts sets of 1807 and 1808, and that other designs from the set were waiting to be discovered. But when I looked more closely at the drawing and coloring, that idea and the idea that this design was by Blake began to fade. The nose, chin, lips, and eyes of the angel in profile looked wrong, wrong enough for me to enlarge and enhance the high-resolution image and compare the copy to its model in the Butts series (illus. 1).

Right: Adam and Eve Asleep, Butts set (Butlin 536.5), detail of angels’ heads. Image courtesy of the William Blake Archive. © 2017 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Accession number 90.102.

See enlargement.

Right: Adam and Eve Asleep, Butts set (Butlin 536.5), detail of foliage, bottom left corner.

Image courtesy of the William Blake Archive. © 2017 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Accession number 90.102.

See enlargement.

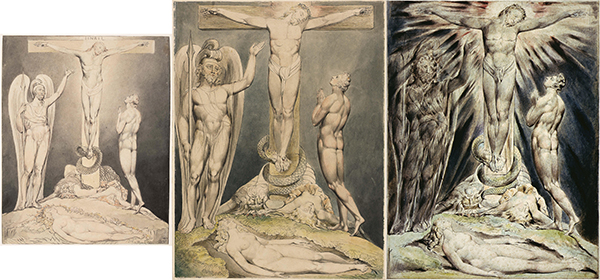

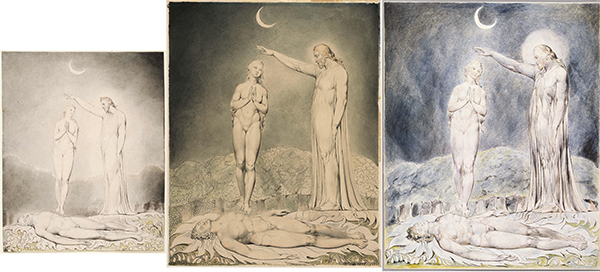

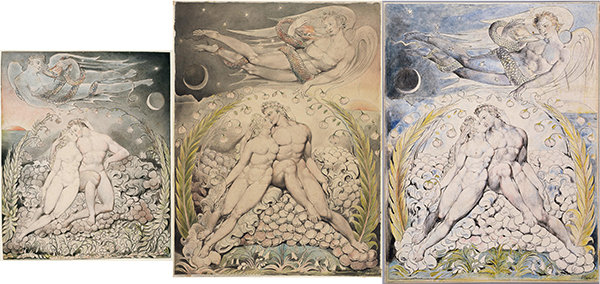

Like the three drawings in the Linnell Paradise Lost set, Adam and Eve Asleep was worked up from a tracing of the Butts version; however, it adhered slavishly to its model, whereas all three Linnell designs display numerous variants and greater freedom in drawing and coloring. For example, compare the three versions of Michael Foretells the Crucifixion (illus. 3) or The Creation of Eve (illus. 4) or Satan Watching the Endearments of Adam and Eve (illus. 5) and you see that in the Linnell versions Blake improvised, taking the kinds of liberties that an original artist takes when copying his own inventions.

Image courtesy of the William Blake Archive. © Courtesy of the Huntington Art Collections, San Marino, California. Object number 000.12.

Center: Michael Foretells the Crucifixion, Butts set (Butlin 536.11). 50.2 x 38.1 cm. Image courtesy of the William Blake Archive. © 2017 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Accession number 90.101.

Right: Michael Foretells the Crucifixion, Linnell set (Butlin 537.3). 50.2 x 38.5 cm.

Image courtesy of the William Blake Archive. © Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. Object number PD.49-1950.

See enlargement.

Center: The Creation of Eve, Butts set (Butlin 536.8). 50.3 x 40 cm. Image courtesy of the William Blake Archive. © 2017 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Accession number 90.95.

Right: The Creation of Eve, Linnell set (Butlin 537.2). 50.4 × 40.7 cm. Image courtesy of the William Blake Archive. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Accession number 1024-3.

See enlargement.

Center: Satan Watching the Endearments of Adam and Eve, Butts set (Butlin 536.4). 50.5 x 38 cm. Image courtesy of the William Blake Archive. © 2017 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Accession number 90.96.

Right: Satan Watching the Endearments of Adam and Eve, Linnell set (Butlin 537.1). 52.8 × 39 cm. Image courtesy of the William Blake Archive. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Accession number 1025-3.

See enlargement.

Linnell’s three Paradise Lost designs are coherent in drawing and coloring styles and differ from their models in similar ways; Michael Foretells expresses the greatest “degree of Liberty,” the most dramatic departure, and Satan Watching the least, but in each we see Blake improvising quite literally in a higher key. Adam and Eve Asleep does not fit into the trio of Linnell designs, not in drawing or coloring style, the latter of which is flat and similar to its model but is a style that Blake hadn’t practiced in over a decade. Its many differences in drawing and coloring styles indicate that it was not part of Linnell’s set and that his set is complete as it is, comprising related but nonsequential illustrations presented as autonomous designs. Adding the copy to this coherent set of three designs is like inserting into a well-composed song a section whose voicings and textures disrupt the harmonious whole.

If we assume that Adam and Eve Asleep is by Blake, an example of his unevenness as a draftsman, and that it was executed for Linnell in 1822 along with Linnell’s three known designs, then we are assuming that Blake behaved uncharacteristically: he overtly improvised with three of four designs but adhered slavishly to the model in one; he colored three in a similar style and palette characteristic of the period but colored one in flat washes applied in a manner he had abandoned years earlier. Equally unsettling is his using a sheet of wove paper when the other three are on laid paper. The paper in Blake’s other watercolor designs to Milton’s works is uniform in type and stock, as it is in the illustrations to the book of Job that Blake executed for Linnell in 1821 and in the illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy that he executed for Linnell in the last two and a half years of his life. Why would Blake use different kinds of paper when executing four Paradise Lost designs for Linnell? Different surfaces and weights of paper affect the finished look of designs. Where different papers in the same project do exist, they signal different periods of execution. Butts’s set of twenty-one illustrations to the book of Job, c. 1805, has two leaves of laid paper among nineteen leaves of wove paper (550.17 and 20), but, as Butlin has argued conclusively, the different papers, along with different (early and late) coloring styles, prove that the two designs were not executed with the other nineteen. Both leaves show traces of “another hand,” possibly “Mrs. Blake’s” (catalogue entries for 550.17, 20). Arguing that the copy of Adam and Eve Asleep was added to the Linnell designs after the three designs on laid paper were executed, like the two leaves in Butts’s book of Job, might seem to explain the presence of different papers, but it makes the early style of laying in washes all the more incongruous and uncharacteristic.

Another factor that concerns me is the near absence of the kind of pen and ink outlining present in Blake’s other finished illustrations as well as late illuminated prints. This kind of outlining is exceedingly difficult to do and requires a master’s hand. Cennini was right about keeping pen and ink from art students for at least the first year of their training! Adam and Eve Asleep looks like the work of a student who knew how to trace a model and lay in flat washes (though the black shadowing in the foliage at the bottom is a bit heavy handed—see illus. 2) but was not able to finish it in the style that required more expertise. As a result, the drawing looks slightly out of focus compared to the three Linnell designs—indeed, to other finished drawings by Blake.

Taken together, the material facts of the newly discovered copy of Blake’s Adam and Eve Asleep—its lack of variants, its awkwardly drawn facial and other details, its different style of laying in washes, its absence of pen and ink outlining, its different support—lead me to believe that we are looking at a copy of a Blake drawing and not a design poorly drawn by Blake.