Posthumous Blake:

The Roles of Catherine Blake, C. H. Tatham, and Frederick Tatham in Blake’s Afterlife

Joseph Viscomi is the James G. Kenan Distinguished Professor of English Literature at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He is the author of Blake and the Idea of the Book and co-editor, with Robert Essick and Morris Eaves, of the William Blake Archive. His current project, “Printed Paintings,” examines the techniques, histories, and meanings of Blake’s large monoprints.

2. 1827–28: Catherine Blake Resides in John Linnell’s Studio and Prints Blake’s Etchings and Engravings 3. 1828: Catherine Blake Leaves Linnell’s Studio under the Auspices of Frederick Tatham 4. 1828–29: Catherine Blake Resides in Mayfair at the Office and Studio of C. H. Tatham 5. 1829: Catherine Blake Prints Copies of America and Europe in Mayfair after Moving to Her Apartment 6. 1831–32: Frederick Tatham Prints Illuminated Books in the Mayfair Studio 7. 1831–32: Posthumous Songs Reexamined 8. 1832: Posthumous Printing Stops 9. 1832: Financial Troubles at 34 Alpha Road, 1 Queen Street, and 20 Lisson Grove North 10. 1833: C. H. Tatham’s Auction and Sale and Letters to Sir John Soane 11. 1829–31 Revisited: Catherine Blake’s Apartment and Her Role in Posthumous Productions 12. 1788–1827 Revisited and Prices for Works in 1827–31 13. Summary of Argument

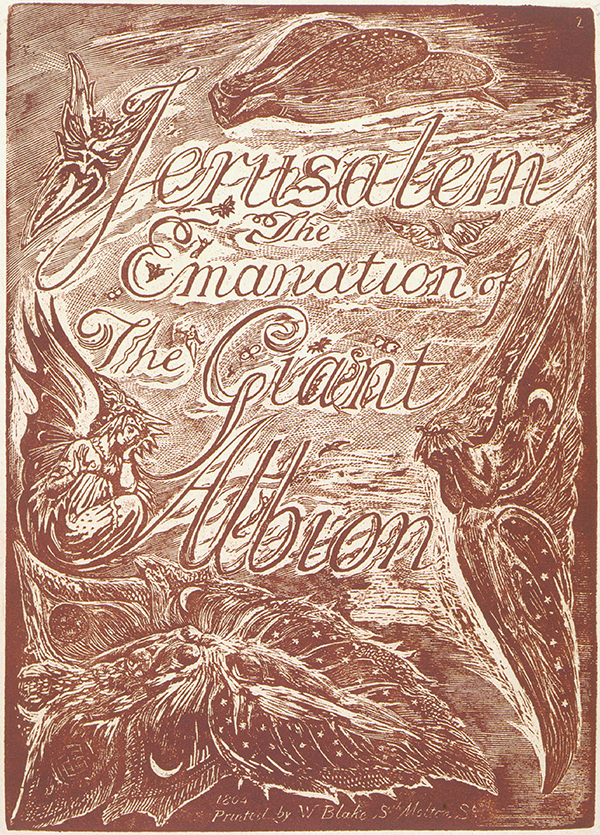

1. Blake, Posthumously Printed

My wife is like a flame of many colours of precious jewels …. (Blake, letter to William Hayley, 16 September 1800; Erdman [hereafter E] 709) His widow, an estimable woman, saw Blake frequently after his decease: he used to come and sit with her two or three hours every day. These hallowed visitations were her only comforts. … He advised with her as to the best mode of selling his engravings. (Anon., “Bits of Biography,” Monthly Magazine [March 1833]: 245)The following essay,I am pleased to dedicate this essay to my friend G. E. Bentley, Jr., the better bibliographer whose many works on Blake made this one—and so many others—possible. I am grateful to Bob Essick for reading numerous versions of each section over the past six years, for his patience, suggestions, and insights. I am also grateful to Elizabeth Shand for copyediting, Grant Glass for securing images for reproduction, and, especially, to Sarah Jones for her many queries and corrections. What errors remain are mine alone. though long, detailed, and comprising thirteen parts, focuses on just seven basic questions: Which of Blake’s illuminated works were produced after his death? Who produced them? Where and when were they produced? How were they sold? Why do so many posthumous copies of Songs of Innocence and of Experience seem incomplete? Why did posthumous production stop? Answering these questions requires examining closely and thoroughly the bibliographical evidence provided by posthumous prints as well as new biographical facts about Catherine Blake, Charles Heathcote Tatham, and his son Frederick Tatham. It also requires tracing the probable location and movement between 1827 and 1832 of the rolling press used to print Blake’s plates.

Frederick Tatham cared for the widowed Catherine and came to possess all of Blake’s effects after she died in October 1831. He did not inherit Blake’s works in a legal sense; no will written by Catherine giving the works to him is extant. He claimed in his “Life of Blake” manuscript that she had “bequeathed” to him the copperplates “as well as all of [Blake’s] Works that remained unsold at [her] Death being writings, paintings” (Bentley, Blake Records, 2nd ed. [hereafter BR(2)] 688).John Linnell, Blake’s last patron (1818–27), contested Tatham’s claims and believed Blake’s effects should have gone to Blake’s sister, Catherine. For an overview of Mrs. Blake’s death and what transpired immediately afterwards, see BR(2) 545-47, 551-56. The exact size of Tatham’s bounty is unknown, but it must have been substantial, given Blake’s claim to have “written more than Voltaire or Rousseau—Six or Seven Epic poems as long as Homer and 20 Tragedies as long as Macbeth” (BR[2] 496). In addition to Blake’s manuscripts, Catherine appears to have inherited over 350 drawings and sketches and at least eighteen copies of Poetical Sketches and Descriptive Catalogue (Bentley, Desolate Market 65-66, 81). Because, as will be demonstrated, she sold relatively few items, “Tatham came into possession of so large a stock of Designs and engraved Books, that he has, by his own confession, been selling them ‘for thirty years’ and at ‘good prices’” (Anne Gilchrist; see H. H. Gilchrist 130). Mrs. Gilchrist was grossly mistaken, however, if she thought that Tatham had been selling Blake’s illuminated books, as though Blake’s stock of them was so large that it took thirty years to deplete.Anne Gilchrist’s idea that Tatham had inherited numerous illuminated books may have come from Allan Cunningham, who stated in 1830 that Blake still had “many copies” at the end of his life (BR[2] 654).

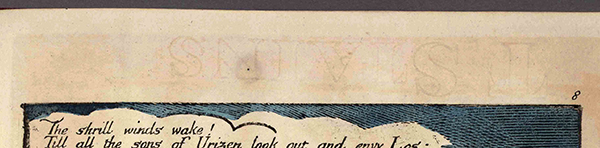

From the known provenances of Blake’s illuminated books and the patterns of production of his late copies from c. 1818 to 1827 and of the copies printed posthumously from c. 1827 through 1832, we can safely infer that Blake left very few complete copies. Catherine inherited Visions of the Daughters of Albion copy N, Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy W, the Small Book of Designs copy B, the highly finished Jerusalem copy E, over fifty loose impressions of There is No Natural Religion, a copy of All Religions are One, loose impressions of The Ghost of Abel and On Homers Poetry, three copies of For the Sexes: The Gates of Paradise and many loose impressions, and at least one copy of For Children: The Gates of Paradise.Plate numbers and copy designations for Blake’s illuminated books follow Bentley’s Blake Books. She would have necessarily inherited the nearly 100 miscellaneous proofs and discarded impressions of illuminated plates from 1789 to 1827 that Tatham sold in volumes of Blakeana (see section 10). Blake appears to have left no copies of The Book of Thel, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, America a Prophecy, Europe a Prophecy, The Book of Urizen, The Book of Ahania, The Book of Los, The Song of Los, or Milton a Poem. Surely Linnell was not exaggerating when he told George Cumberland on 18 March 1833 that not even Blake had copies of all the titles (BR[2] 554).

Catherine sold Blake’s last copies of Visions and Songs in 1829 and 1830 respectively, leaving Tatham with many loose prints but very few illuminated books. Indeed, Tatham’s stock of “engraved Books” consisted almost exclusively of posthumously printed impressions, which, in terms of the number of individual images or leaves, came to compose the bulk of his “inheritance.” As we will see, America, Europe, and Jerusalem were each printed posthumously three times; For the Sexes was printed to produce enough impressions for four copies; and Songs was printed at least ten times—possibly eleven—in three printing sessions. These works account for around 1150 extant posthumous relief etchings, etchings, and engravings. The presence of intaglio impressions and of blemishes in the shallows of relief-etched impressions demonstrates the use of a rolling press—presumably Blake’s. The sheer number of impressions represents much time and labor and raises critical questions: Who printed them and why? When and where?

Because most posthumously printed copies of illuminated books contain leaves watermarked 1831 or 1832, or both, Tatham, who took possession of the copperplates in the fall of 1831, appears responsible for printing most of them. But because Catherine was still alive during much of 1831, G. E. Bentley, Jr., suspects that she and Tatham collaborated on printing the “copperplates of America, Europe, Jerusalem, and the Songs” (Stranger 442). Angus Whitehead agrees, suspecting that she “may have printed plates of America …, of Jerusalem copies H, I, J …, and of Songs of Innocence and of Experience copies a, b, c, d, f, g1, g2, i, j, k, l, [and] o” (“Last Years” 79n35). His research into Catherine’s last residences has led him to suggest that, in the two-room apartment in which she resided for the last two years of her life, she “continued her husband’s trade, printing, coloring, and selling works up until her death” (89). In another essay, Whitehead and Mark Crosby portray her as an independent artisan who continued the “firm” of “Wm Blake” (Crosby and Whitehead 106).

Identifying which works are posthumous and who printed them affects our understanding of Blake, Catherine Blake, and Frederick Tatham. Did the widow Blake print and color illuminated plates up until her death? If so, was she, as this would imply, the primary posthumous printer? Or did she collaborate with Tatham in producing posthumous works? Or did Tatham produce the majority of posthumous prints after Catherine died?

2. 1827–28: Catherine Blake Resides in John Linnell’s Studio and Prints Blake’s Etchings and Engravings

Blake died on 12 August 1827 and was buried five days later. On 18 August, Linnell contacted James Lahee, the printer of the Job engravings, about Blake’s rolling press. According to Bentley, Linnell asked Lahee “if he wanted to buy Blake’s press” (BR[2] 467). He presumably intended to raise money for Catherine Blake. According to Whitehead, however, Linnell sought to trade the press for a smaller one (“Last Years” 77). Lahee’s letter to Linnell supports the idea of a trade: Sir In answer to your note as to Mrs Blakes press I beg to say that I am not in want of a very large press at this moment, but if it happens not to be larger than Grand Eagle, and it is a good one in other respects I have one idle which would answer Mrs B’s purpose, and which I would exchange with her for but the fact is that wooden presses are quite gone by now & it would not answer me to give much if any Cash; notwithstanding the circumstances you mention would prevent my attempting to drive a hard bargain …. (BR[2] 467) The phrases “would answer Mrs B’s purpose” and “I would exchange with her” do suggest that Catherine “appeared intent on continuing to print from a rolling press, presumably in an effort to market her husband’s works and support herself” (Whitehead 77). George Cumberland, Jr., thinking that was her intention, wrote his father c. 16 January 1828 that Mrs. Blake “intends to prin[t] with her own hands [her late husband’s works] and trust to their sal[e] for a livelihood” (BR[2] 482). Before we can ascertain how much of her intent she realized in practice and how realistic it was, we need to locate where she set up her printing press.

Lahee informed Linnell that “wooden presses are quite gone by now.” After sending an assistant to evaluate Blake’s press, he declined Linnell’s offer. On 30 August 1827, Linnell moved the old press, not a trade-in, from the Blakes’ residence at 3 Fountain Court, the Strand, to his studio at 6 Cirencester Place, Fitzroy Square (BR[2] 468). Catherine followed two weeks later, on 11 September (BR[2] 471), presumably with her belongings and all of Blake’s books, manuscripts, copperplates, large color prints and their matrices, portfolios of sketches and drawings, temperas and watercolors, frames, canvases, and stretchers, the large painting Blake was working on at the end of his life, and printing and painting supplies, materials, and tools. The move no doubt involved “a great deal of Luggage,” as Blake termed their worldly possessions when, in 1800, they moved from Lambeth to a cottage in Felpham to be near his then-patron William Hayley. But this time, given that Blake had sold his print collection to Colnaghi in 1821, Catherine’s move—in addition to the rolling press—probably involved fewer than the “Sixteen heavy boxes & portfolios full of prints” that she and Blake took to Felpham (E 710, BR[2] 99). At Linnell’s studio, she was to be granted a nominal income as housekeeper (BR[2] 538-39). These arrangements were, according to Alexander Gilchrist, “in part fulfilment of the old friendly scheme” (1: 365).The historical record regarding Catherine’s finances at the time of Blake’s death is confusing. She appears to have needed to borrow £5 from Linnell to help with the burial costs, though having just received from William Young Ottley through Linnell £5.5s. for Jerusalem copy F (Viscomi, Blake and the Idea of the Book [hereafter BIB] 357). She is reputed to have received a gift of £100 from the king’s sister Princess Sophia, which she returned, claiming others were more in need than she. Yet in mid-August 1827, encouraged by John Constable, Linnell had taken up her cause with the Royal Academy, which proved unsuccessful (BR[2] 460-63). Returning Princess Sophia’s gift seems unlikely if it had actually been given—or an extraordinary and inexplicable rejection. The source of the story about the princess was Seymour Kirkup, who was in Italy at the time; that Linnell does not mention the gift makes its existence doubtful. Catherine did withdraw an application for assistance from the Artists’ General Benevolent Institution in early 1830, but appears to have done so because by then she felt financially secure (see section 5).

Linnell had been actively trying to help William and Catherine Blake financially since June 1818, when he hired Blake to assist him in engraving the portrait of James Upton, pastor of the Baptist Church, Church Street. In addition to being a portrait and landscape painter (preferring the latter but needing the former to support his growing family), Linnell was an accomplished, albeit self-taught, graphic artist. He exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy’s annual exhibitions and was recorded in its catalogues as “painter and engraver” (Graves, Royal Academy 5: 64). By the time he met Blake in 1818, he had already etched or engraved twenty-one portraits and landscapes after his own designs.Linnell’s first engraving, in 1813, was after his portrait of John Martin, pastor of the Baptist Church, Keppel Street, Bloomsbury, which he had joined in 1812. This is where he met Charles Heathcote Tatham, father of Frederick (Story 1: 73). The engraving of Martin, according to Alfred Story, sold “upwards of seven hundred copies” (1: 71). Linnell collected old master prints and had examples of Dürer, Holbein, Raimondi, and Bonasone. Blake’s examining “ancient” engravings with Linnell eventually led to his adopting some of Linnell’s burnishing techniques (see Essick, Printmaker 223) and to the pure engravings of the Job illustrations (see Viscomi, Blake and His Followers 10-11). Linnell was thirty-five years younger than Blake and not in a position to provide charity, but apparently he quickly realized Blake’s precarious financial situation and soon took on the role of agent and, eventually, patron. Over the next several years, he found Blake customers for his illuminated books and designs, bought copies of the illuminated books (including Songs, Marriage, America, and Europe) and designs (including those for Milton’s Paradise Regained), and commissioned works (including designs from Paradise Lost, a second copy of the Job watercolors and the engravings after them, and 102 Dante watercolor illustrations and seven engravings after them). By 1826, he was concerned for Blake’s physical wellbeing.

That summer, Linnell had begun urging the Blakes to move closer to him, first near his cottage in Hampstead and then, when that failed, to Cirencester Place (A. Gilchrist 1: 350-55). On 7 February 1827, he wrote in his journal, “to Mr Blake. to speak to him @ living at C. P” (BR[2] 455), which was at Fitzroy Square, the neighborhood of Blake’s brother James and former patron Thomas Butts.Butts lived at 17 Grafton Street, Fitzroy Square, between 1808 and 1845 (Viscomi, “Green House” 10-11). As Bentley notes, “The reference does not make clear whether the Blakes were to move into Linnell’s studio, into independent lodgings, or into the building where Blake’s brother James lived” (BR[2] 455n). Exactly where probably did not matter to Blake, because moving required changes and that alone elicited terror and terrible anxiety. He wrote to Linnell a few days later, “I have Thought & Thought of the Removal. & cannot get my Mind out of a State of terrible fear at such a step. the more I think the more I feel terror at what I wishd at first & thought it a thing of benefit & Good hope” (E 782). Instead, the Blakes spent Blake’s last year in their two-room apartment at Fountain Court, where they had lived since 1821.

The Cirencester Place residence appears to have been used as Linnell’s studio. Catherine’s housekeeping would have been less demanding here than at the family’s Hampstead residence, where Linnell and his wife were raising five children between the ages of one and nine—a brood that would eventually become nine by 1835.William, James, John, Elizabeth, and Hannah, ages one, four, six, seven, and nine (Crouan xxii-xxiii). Whitehead also notes that there is no evidence that Catherine took care of Linnell’s children (“Last Years” 77n15). A working rolling press in the studio would certainly have been to Linnell’s advantage—as would a tenant who was a skilled printer. Catherine knew how to print both intaglio plates, like Blake’s etchings and engravings, and relief-etched plates, like those making up illuminated books. According to Blake, in 1803 she had “undertaken to Print the whole number of the Plates” for Hayley’s The Life, and Posthumous Writings, of William Cowper, which she did “to admiration & being under my own eye the prints are as fine as the French prints & please every one” (E 726-27). The print-run for the first edition was 500 copies, indicating that Catherine pulled 2000 impressions of four engravings, which earned her “Twenty Guineas” (E 727)—2.5 pence per impression.Hayley recognized the labor involved, noting that Blake “and his good industrious Wife together take all the Impressions from the various Engravings in their own domestic Press” (BR[2] 151). That, however, is not quite accurate. Blake executed six plates in Hayley’s three-volume Cowper and designed one of them, the second plate in volume 2. Catherine printed the four plates in volumes 1 and 2 of the first edition. According to Crosby and Whitehead, she may have printed the second edition as well. The “plates in the first edition are poorly inked and wiped compared with the second edition,” which they read as “suggesting that Catherine improved her techniques with practice” (99) rather than as the work of another printer, which, as Robert N. Essick notes, “may indeed be the case” (Commercial Book Illustrations 86). Crosby and Whitehead also suggest that Catherine may have printed other commercial engravings after 1800 (99). Printing intaglio plates well took skill and experience in both inking the plate and wiping the ink from the plate, first with muslin rags and then with the palm of the hand covered with whiting. Printing intaglio plates without an assistant, as Catherine appears to have done, is especially daunting, because in addition to inking plates, the printer has to cut sheets into leaves and dampen them for printing, to deliver leaves to plates using paper or metal tongs to keep from touching the leaves with inky fingers, to register leaves to plates correctly, to pull plates through the press with the right pressure, and to arrange impressions to dry without offsetting one onto another. Blake told Hayley that Catherine printed the relief-etched broadside Little Tom the Sailor, “a few in colours and some in black which I hope will be no less favour’d tho’ they are rough like rough sailors. We mean to begin printing again to-morrow” (26 November 1800, E 714). Even with an assistant, this was no easy task, because the work comprised four plates: head- and tailpieces etched in white line, long text plate etched in relief, and a narrow, wide colophon (3.5 x 12 cm.) etched in relief. These needed to be inked, aligned on the press bed, and printed on a sheet of paper to reconstruct the composition.Because illuminated plates were not uniform in size, a uniform bottom sheet for the series marking the alignment of plate to paper could not be used. Consequently, paper had to be registered to the plate by eye to create proper and pleasing margins. The quality of plate registration in the early copies of illuminated books is uneven, with plates tilted left and right, off center, or falling or rising on the page with too much top or bottom margin (the Blakes apparently gave themselves a very wide margin of error). These visual effects are obscured when the leaves are presented in mats or cropped to the image. They are also obscured in reproductions, even in the Blake Archive, because designs are cropped for economic and aesthetic reasons: showing entire leaves requires more paper or creates larger files and reduces the size of the printed image (see Viscomi, “Digital Facsimiles”).

While Catherine was staying in Linnell’s studio, Linnell was probably still etching—or proofing—eight heads for John Varley’s Treatise on Zodiacal Physiognomy and/or six facsimile copies of old line engravings after figures in the Sistine Chapel, both published in 1828. She may have helped Linnell proof or print some of his plates, and/or he may have helped her print some of Blake’s intaglio plates, including impressions of the Dante engravings and “Canterbury Pilgrims” that he recorded in his general accounting book for 5 September 1827 (BR[2] 790).The 5 September entry is after the press arrived but before Catherine was in residence. The impressions may have been printed to test the set-up of the press. Seven entries in Linnell’s general accounting book between September 1827 and March 1828 are “To Mrs Blake.” These range from £1 to £5, which could account for her assisting him at the press (BR[2] 791). The latter impressions may have included the three she sold on 8 January 1828 to Henry Crabb Robinson and Barron Field (BR[2] 480, 705-06).

With her press (and Linnell’s studio) set up for intaglio printing, Catherine seems likely to have also printed copies of For the Sexes: The Gates of Paradise, Blake’s emblem book comprising twenty-one small etchings. Blake had first executed the work in 1793 as For Children: The Gates of Paradise, which he advertised in his prospectus of 1793 as “a small book of Engravings” (E 693). For Children has eighteen plates in two states; five copies are extant (A-E; Bentley, Blake Books [hereafter BB] 186). Around 1818, Blake brought all but plate 11 to a third state and added three text plates (19, 20, and 21), transforming the work into For the Sexes. He appears to have printed For the Sexes copies A and B together, on paper approximately 16 x 11 cm., watermarked J Whatman / 1818, possibly a ninth of a foolscap sheet (42.5 x 34.5 cm.).Copy A is untraced, but its recorded leaf size matches the leaf size of copy B (BB 194), three of whose leaves are watermarked J Whatman / 1818. Linnell acquired both copies, probably directly from Blake, though when and how are not known.Linnell’s general accounting book for the period has an entry “For prints” on 10 December 1820, for £1 (BR[2] 780), which has no accompanying receipt and may account for the sale. Blake apparently put For the Sexes away until at least 1825, the date of the J Whatman paper in copies C and D—whose plates 1-10 and 13-18 are in their fourth states, with plates 11, 19, and 21 in their second states, plate 12 in its third state, and plate 20 in its first state. The 22.8 x 14.3 cm. leaves are most likely quarter sheets of printing demy (56 x 45.6 cm.). He returned to the plates one more time, bringing all of them to a new state. Copy E appears to have been the first copy printed with the plates in their final states, presumably c. 1826–27.Plate 12 is in four states; plates 11, 19, and 21 are in three states; plate 20 is in two states; the rest are in five states. For a detailed description of all five states of plate 7 (“Fire”), see Essick, “Marketplace, 2016,” illus. 2. The unmarked leaves are 26.2 x 18.8 cm., possibly quarters of crown sheets (approximately 51 x 38 cm.).

Bentley suspects that copies F, G, H, I, J/N, K, and L were all printed posthumously by either Catherine or Tatham because they are incomplete, larger than copies A-E, and many of them “can be traced to Tatham” (BB 196-97).Recently rediscovered copy N (Blake Books Supplement [hereafter BBS] 79) clearly completes copy J, hereafter referred to as copy J/N. Materially, though, these seven copies form two different groups. The seventy-one impressions forming copies F, G, H, and I were printed on leaves approximately 34 x 24 cm.—apparently quarters of super royal paper (68 x 48 cm.)—watermarked J Whatman / 1826. Copies G and I are missing plate 19 (“The Keys of the Gates”) and copy F is missing plates 19 and 20. Copy H is missing plate 19 and eight other plates, which, on one hand, suggests that the twelve impressions in what we call copy H may be duplicate impressions from the printing session responsible for the three near-complete copies. On the other hand, the leaves of copy H were stabbed, as were those forming copies F, I, J/N, and D, which suggests that copy H was once complete. If so, then its printing session produced around eighty impressions, four per plate minus plate 19, enough to form copies F, G, H, and I, with copy H now missing eight other plates. The impressions making up copies J/N, K, and L appear also to have been printed per plate, not per copy. The plates were printed cleanly on unmarked leaves approximately 37 x 26 cm., quarters of imperial sheets (74 x 54 cm.). The two groups’ different sizes and types of paper strongly suggest different printing sessions; the absence of plate 19 in copies F, G, H, and I and its presence in copies J/N, K, and L suggest two different printers.Copy L’s plates 2, 19, and 20 were added to For Children copy D by Tatham.

At first glance, Catherine appears responsible for copies F, G, H, and I and Tatham for copies J/N, K, and L. But this division is highly unlikely because of what the two groups share. As noted, copies F, H, and I from the first group and copy J/N from the second group were stabbed. This mode of binding was used for illuminated books and possibly undertaken by Catherine; it was certainly known to her as Blake’s assistant in the printing and compiling of illuminated books (BIB 102-05). Stabbing signals her hand in the production of copies F, G, H, and I and excludes Tatham’s from them and from copies J/N, K, and L because none of the illuminated books that he is certain to have printed was stabbed (see section 6).In Blake and the Idea of the Book I missed the significance of these bibliographical facts and recorded the posthumous impressions of For the Sexes as the work of Catherine and/or Tatham (367). I believe now that Blake produced the assortment of proofs and impressions making up copies J/N, K, and L, that Catherine produced copies F, G, H, and I, possibly with the assistance of Linnell, and that Tatham did not print any of Blake’s intaglio plates. The grey and black washes in copy F impressions also support the idea that Catherine was responsible for printing and compiling copy F and, presumably, its sister copies, G, H, and I. Similar washes are in “Joseph of Arimathea” 2F, an impression printed on paper watermarked 1828 (Essick, Separate Plates 5).This impression was “very probably acquired by George Richmond (from Mrs. Blake or Frederick Tatham?)” (Essick, Separate Plates 5). America copy N and Europe copy I, which she appears certainly to have printed (see section 5), were also touched up in black and grey washes throughout. Washes, like stabholes, are absent in the illuminated books that Tatham printed. Washes are also absent in For the Sexes copies A-E, the known lifetime copies that Blake printed, as well as in copies J/N, K, and L, which aligns the production of this second group of copies with Blake. The unmarked leaves of copies J/N, K, and L are similar in texture to the unmarked leaves of copy E, raising the possibility that Blake printed copies E, J/N, K, and L in the same printing session, proofing and printing enough impressions of his plates in their final states to form three or four copies.All fourteen leaves in copy K are approximately 37 x 26 cm.; six of the ten leaves in copy J are also this size. The impressions in For the Sexes copies E, L, and N were trimmed (BB 194-95, BBS 78). The idea that copies J/N, K, and L were printed by Blake is also supported by the order in which the two groups were produced, which can be determined by two scratches on plate 2. Neither is present in copies A through D, one of them is present in E, J/N, K, L, G, H, and I, and both of them are present in copy F, indicating that the group to which copy F belongs—F, G, H, and I—was printed after copies E, J/N, K, and L.The shared scratch is across the “s” in “Paradise”; the unique scratch is across the “P” in “Paradise,” which apparently occurred when the plate was printed for copy F. Plate 2 has other scratches, most noticeably three at the top left corner under the “F” in “For” of the title; these scratches first appear in copy E and remain in all subsequent copies. Blake apparently did not find the accidental scratches at the top of plate 2—or the scratches in other plates—troublesome.

Bentley is right to trace many copies of For the Sexes to Tatham. Indeed, the number of copies that Tatham inherited also supports the idea that Blake, not Tatham, printed copies J/N, K, and L. He inherited For Children copy D and For the Sexes copies C, D, E, and F, and probably copies G and H (BB 201-03).According to a 1929 Sotheby’s sales catalogue, copy I was “believed” to have been given to Joseph Dinham (BB 203), who was one of six people at Catherine’s funeral (BR[2] 547). He was a sculptor and protégé of the sculptor Sir Francis Chantrey, who knew Blake and had acquired a copy of the Job engravings in 1826. Dinham may have learned of Blake through Chantrey and acquired copy I directly from Catherine, whom family tradition had assumed to be Blake. As we will see, America copy N and Europe copy I were also printed by Catherine but thought by late owners to have come directly from Blake. He gave copy F as a gift “to Mr. Bird on his attendance at the Funeral Oct 23r.d. 1831—being the day on which the widow of the author was Buried in Bunhill Fields Church Yard” (BB 202). He sold copies C and D c. 1833 to Samuel and Thomas Boddington, respectively. He sold For Children copy D with plates 2, 19, and 20 from For the Sexes copy L to Frederick Locker (BB 192); he also sold Locker For the Sexes copy E (BB 202). Tatham’s possession of four or more copies in late 1831 probably would have removed his incentive to print more copies during this time—between 1831 and 1833. Moreover, the illuminated books he did print are all on J Whatman paper dated 1831 and 1832, and the press needed to print them was no longer accessible after 1832 (see section 9). The dates of exchanges—copy F followed by copies C, D, and E—also rule out Tatham as having extracted plate 19 from Catherine’s copies (F, G, H, and I) because he did not extract plate 19 from the other copies he obtained from her. Plate 19 is probably missing from copies F-I for the reason proposed by Bentley: “Pl. 19 was engraved on the verso of pl. 20 and was thus easy to overlook” (BB 196).Bentley deduces that plates 19 and 20 share one piece of copper from their shared plate sizes. Blake’s relief-etched plates provide many precedents: the plates for Experience, Europe, and Urizen, for example, are on the versos of the plates for Innocence, America, and Marriage, respectively. Etching on both sides of an intaglio plate, however, was extremely unorthodox. Printers would assume the verso of an etching, engraving, or stipple was blank, because a design on the verso could be easily scratched while the plate was on the work bench or brazier, where the recto was inked. Scratches would show up in the verso’s printed design as thin black lines across white paper. Blake could relief-etch both sides of plates because such scratches across the relief line system were filled in by ink and/or hidden in finishing. Plate 19, in other words, was not printed. This mistake in production makes it probable that copies F–I were printed apart from copies J/N, K, and L, that the two groups were produced by different printers, and that one of the printers knew the work better than the other.

In addition to the copies mentioned above, Tatham also sold loose impressions from copies J/N and L as part of volumes of prints and proofs that he put together for sale (BB 131, 203, BBS 79). For Tatham to have sold lifetime copies and impressions means that Blake printed most—if not all—of his late copies of For the Sexes on speculation, not commission. Catherine appears to have done the same, adding four copies to the copies and pile of impressions that she had inherited, presumably hoping to build up her stock of this title in preparation for selling. She appears not to have realized that objective: the monies from the sales of the copies that she and Blake printed went to Tatham. That cold economic reality casts doubt on the assumption that Catherine had succeeded in supporting herself by printing Blake’s works. As we will see in section 12, the market she needed for Blake’s work to provide a viable income did not yet exist; the prices that his illuminated books were fetching were not sufficient to make her or anyone financially independent—including Tatham, who sold Blake’s works for thirty or more years to supplement his main income, which came from portraits in pastels and watercolors.

One copy of For the Sexes that did not pass through Tatham’s hands was copy K. Linnell owned it and almost assuredly acquired it either from Blake or Catherine Blake, because by early 1831 Linnell was on litigious rather than speaking terms with Tatham, who accused Linnell of owing Catherine money for the Dante designs and later claimed them as his own (BR[2] 537ff., H. H. Gilchrist 130). Linnell’s owning copy K is interesting because he already owned copies A and B. As noted, plates 1-18 in copies A and B were in their second and third states, c. 1818, with plates 19-21 in their first states. The copy K impressions were in their final states, c. 1826–27, which included visual effects created by burnishing that Blake learned from Linnell (Essick, Printmaker 223). Perhaps Blake made a gift of the loose impressions to show his patron the latest versions of these designs, or Catherine gave them in thanks for his hospitality. However Linnell obtained them, they are from a larger assortment of prints and proofs that have been mistakenly identified as posthumous. Removing this late assortment of prints—copies K, J/N, and L—increases the number of lifetime proofs and impressions of For the Sexes and leaves only copies F, G, H, and I as posthumously printed. This latter group was printed by Catherine, presumably at the Cirencester Place studio, when she and Linnell were printing and proofing various intaglio plates.

3. 1828: Catherine Blake Leaves Linnell’s Studio under the Auspices of Frederick Tatham

When Catherine Blake left Linnell’s, she appears to have printed intaglio works but not yet any of the relief-etched illuminated books. At the very least, Cumberland Jr.’s comment about her intending to print her husband’s works—by which he appears to have meant the relief etchings, but perhaps also Blake’s book of emblems—suggests that she hadn’t done so as of mid-January 1828. She apparently moved to Tatham’s with all of her and Blake’s belongings, including the press. Although the press’s presence at Tatham’s is not documented textually, it is evinced materially, as we will see, in the form of copies of America and Europe that can be traced back to Catherine during the period she was under his care. The exact lengths of her residencies with Linnell and Tatham are not clear, however, nor is the location of the latter residency, because Alexander Gilchrist is mistaken about when she left Linnell’s and silent on the location of Tatham’s “chambers.”

According to Gilchrist, Catherine remained at Linnell’s for some nine months; quitting in the summer of 1828, to take charge of Mr. Tatham’s chambers. Finally, she removed into humble lodgings at No. 17, Upper Charlotte Street, Fitzroy Square, in which she continued till her death; still under the wing, as it were, of this last-named friend. The occasional sale to such as had a regard for Blake’s memory, or were recommended by staunch friends like Mr. Richmond, Nollekens Smith and others, of single drawings, of the Jerusalem, of the Songs of Innocence and Experience, secured for her moderate wants a decent, if stinted and precarious competence. (1: 365) Catherine sold Songs copy W in March 1830 for £10.10s. to John Jebb, Bishop of Limerick (BB 423). Jerusalem copy E, elaborately colored and valued by Blake at “Twenty Guineas” (E 784), certainly one of Catherine’s most valuable single artifacts, was sold by Tatham (BB 259-60). But this oversight is less troublesome than the many confusions and ambiguities in this oft-quoted passage.

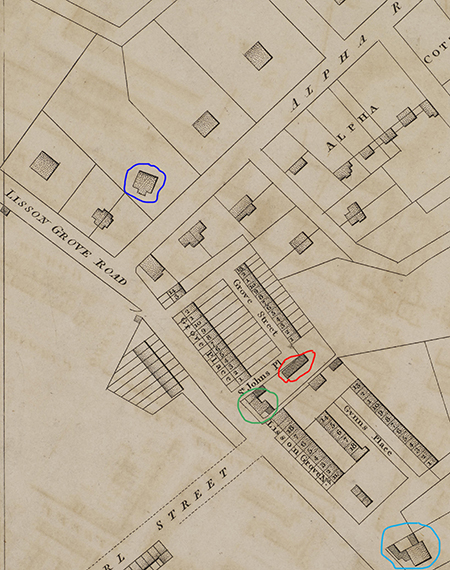

Whitehead dates Catherine’s departure from Linnell’s studio as “c. March 1828” (“Last Years” 80), noting that Linnell’s poor health because of overwork may have figured into her decision to move to Tatham’s (80n42). An entry in Linnell’s accounting book for April 1828 reads, “To Mrs Blake (furniture sold) [£]1 10” (BR[2] 791). With either a March or an early April departure, she appears to have stayed with Linnell less than seven months, not nine. And rather than staying with Tatham for two years, as is generally thought, she appears to have resided with him for only one year, arriving by April 1828 and leaving by early April 1829. Tatham implies a one-year residency with these parameters in a letter of 11 April 1829,Bentley dates the letter as 11 April (BR[2] 755) and as 1 April (BR[2] 495). In Blake Records Supplement [hereafter BRS], he dates it 11 April 1829 (90n178). In private conversations, he confirmed the date as 11 April 1829. in which he states that Catherine had already moved to her own apartment. Writing to an unknown patron who had inquired about Blake’s books (see section 5), he apologized for his delayed response, explaining that as a “consequence of Mrs. Blake’s removal from Fountain Court to No. 17. Upper Charlotte St Fitzroy Square, a wrong address was put on the letter at Fountain Court and it was only received by her the day before yesterday” (BR[2] 495).Tatham does not mention Catherine’s yearlong stay with him (or the almost seven months she stayed with Linnell), implying, intentionally or not, that she had been living independently since the death of her husband. Her first forwarding address from Fountain Court was Linnell’s studio at 6 Cirencester Place, but Linnell is unlikely to have forwarded the 1829 letter to Tatham, as Bentley suggests (BR[2] 495n), because Catherine had left Linnell’s studio in spring 1828. The letter was presumably forwarded from Fountain Court to one of the Tathams’ residences, either 1 Queen Street, Mayfair, or 34 Alpha Road.

Bentley correctly records that Catherine left Tatham’s residence in spring 1829, but he also dates her stay with Tatham as 1828–30—that is to say, as being concurrent with her lodgings at 17 Upper Charlotte Street (BR[2] 754-55). He notes that Catherine’s address is in doubt, because in Tatham’s letter of 18 October 1831 and in the documents for her burial of 20 October 1831 the address is recorded as “Upper Charlton Street” (BR[2] 754n). Whitehead’s impressive detective work has confirmed that Catherine moved directly from Tatham’s to 17 Upper Charlton Street, where she stayed from April 1829 until her death on 18 October 1831.For a summary of the confusion over Catherine’s last address, see Whitehead, “Last Years” 86-87. This was a two-room apartment (Whitehead, “Last Years” 89) in the Fitzroy Square neighborhood, where Cirencester Place was located and where Catherine presumably had friends. She did not maintain concurrent residencies but, as we will see, probably had access to Tatham’s residence during this period. Whitehead also discovered that in early 1829 Catherine had inherited £20, along with some furniture, from her brother-in-law Henry Banes, which enabled her to move and to begin living independently.Banes, who died in January 1829, was the husband of Catherine’s sister and the Blakes’ landlord at 3 Fountain Court. See Whitehead, “The Will of Henry Banes.”

According to Bentley, Catherine “moved in with the Tathams in Lisson Grove to look after them” (BR[2] 755). But recently discovered information reveals that Frederick Tatham and Louisa Keen Viney, of Essex, were married 25 April 1831—by which time Catherine had been in her own place at 17 Upper Charlton a full two years.The marriage register can be accessed at the Tatham Family History website, under Frederick Tatham <http://www.saxonlodge.net/showmedia.php?mediaID=109&medialinkID=155>. This resource came online in the past decade and continues to grow. She never “look[ed] after” Tatham and his wife; the idea that she had done so and took an apartment of her own only after Tatham married appears to have originated with Tatham himself. In his “Life of Blake” manuscript, written c. 1832, he states: After the death of her husband she resided for some time with the Author of this[,] whose domestic arrangements were entirely undertaken by her; until such changes took place that rendered it impossible for her strength to continue in this voluntary office of sincere affection & regard. She then returned to the lodging in which she had lived previously to this act of maternal loveliness—in which she continued until she was decayed by fretting & devoured with the silent Worm of grief …. (BR[2] 690) Bentley’s understanding of the phrase “domestic arrangements” to mean marriage appears to have been widespread. According to Henry Curtis, the historian of the Tatham family, “It would appear, from the facts recorded by Gilchrist, therefore, that Mrs. Blake removed from Fredk. Tatham’s chambers on his marriage, and to lodgings almost certainly near at hand.”Quoted in the entry for Frederick Tatham at the Tatham Family History site <http://www.saxonlodge.net/getperson.php?personID=I0840&tree=Tatham>. Curtis’s typescript, “Notes for a Pedigree of the Tathams of Co. Durham, England,” is the basis of much of the genealogy in the site, as well as the current ODNB entries for Tatham, C. H. Tatham, and Richmond (C. H. Tatham’s son-in-law). Curtis presumably read Tatham’s “Life of Blake” as first reproduced in A. G. B. Russell’s The Letters of William Blake (1906).

Tatham’s explanation for Catherine’s departure is ambiguous. She took care of his domestic arrangements, he says, “until such changes took place that rendered it impossible for her strength to continue in this voluntary office,” adding that she “returned to the lodging in which she had lived previously to this act of maternal loveliness—in which she continued until she was decayed by fretting & devoured with the silent Worm of grief” (emphasis added). As noted, Catherine did not have an apartment concurrent with her residency with Tatham—and she did not return to Linnell’s studio. Tatham presumably meant that she returned to her previous Fitzroy Square neighborhood. The “changes” that “took place” were most likely in Catherine’s physical condition in 1830 and 1831. The phrase “in which she continued” appears to modify the “act of maternal” kindness in the form of housekeeping, implying that she remained “still under the wing” of Tatham, as Gilchrist states. But Tatham is clear that Catherine’s declining strength ended her caregiving, which means that she continued to live (and to decline physically) in her own lodgings for the last two years of her life. By mid-1830, as we will see, Tatham appears to have moved to 20 Lisson Grove North. The distance between her Fitzroy Square residence and 20 Lisson Grove North was three miles round-trip, which seems unlikely to have been routinely undertaken by the increasingly frail Catherine.Bentley implies that she may have walked from her lodgings to Grosvenor Place with Lord Egremont’s painting under her arm in August 1829 (BR[2] 498). This distance was about three and a half miles round-trip. If she did walk it over, that does not mean she was in equally spry shape in 1830 or 1831.

4. 1828–29: Catherine Blake Resides in Mayfair at the Office and Studio of C. H. Tatham

Catherine Blake moved to Linnell’s studio on 11 September 1827; her printing press preceded her by about two weeks. By March or early April 1828, she had moved out, presumably with all her belongings, including the press. At the time, Frederick Tatham, twenty-two years old, was still living with his parents, Harriet and Charles Heathcote Tatham, at 34 Alpha Road, Lisson Grove, a relatively new development in Marylebone, west of Regent’s Park. The Alpha Road residence also housed seven of Frederick’s younger brothers and sisters: Robert, Edmund, Georgiana, Maria, Augusta, Harriet, and Julia, all between the ages of three and sixteen.C. H. Tatham’s first child, Charles Howard, born 11 December 1802, died seventeen days later; Lydia, the fourth child, born 27 February 1807, died 22 March 1808. The last seven of his twelve children, starting with Julia, born 24 May 1811, and stopping with Robert Bristow, born 30 May 1824, were born at Alpha Road, suggesting that it had become his main residence by 1811 (Tatham Family History site). Frederick’s unmarried twenty-four-year-old sister Caroline (b. 1803) was possibly still in residence. Their brother Arthur (b. 1808), the future clergyman, was away at Magdalene College, Cambridge, from 1827 to 1831.Arthur Tatham (1808–74) was for more than forty years rector of Broadoak and Boconnoc in Cornwall and, from 1860, prebendary of Exeter Cathedral. This large house belonged to his father, an important neoclassical designer of ornaments, furniture, and silverware, as well as a successful architect.C. H. Tatham was “very involved with the family firm of Tatham Bailey & Sanders” (Galinou 478). His brother Thomas (1762–1818) was apprenticed to John Linnell, the great eighteenth-century cabinetmaker and a distant relative of the Tathams. His brother John was a solicitor, who “dealt with the legal side of Tatham’s transactions” (Galinou 478).

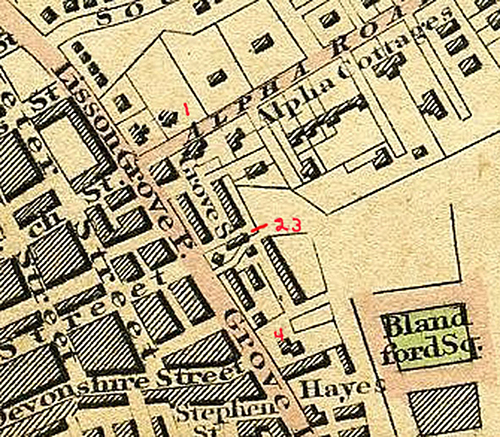

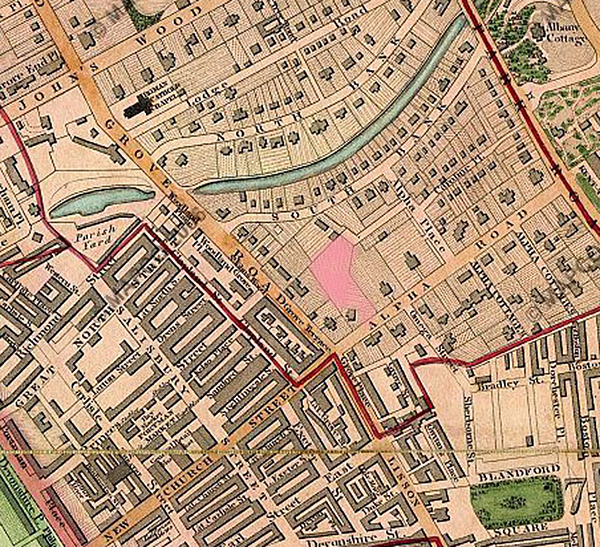

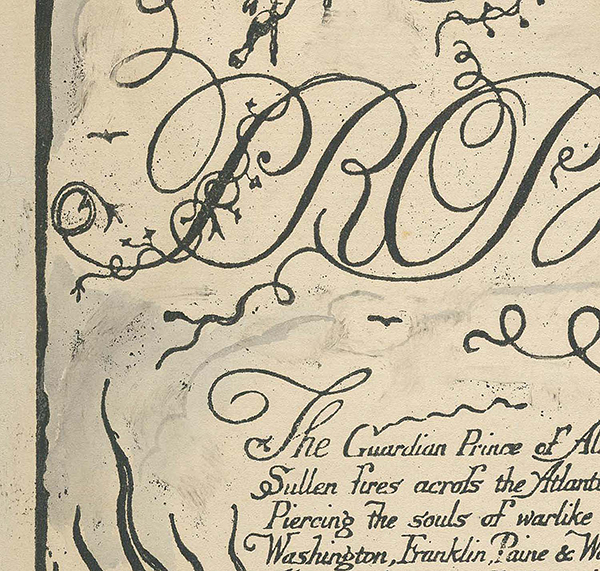

In Cottages and Villas: The Birth of the Garden Suburb, Mireille Galinou explains how Alpha Road was developed from the Eyre estate. C. H. Tatham bought the lease of a house on 2 May 1808 from Alexander Birnie, the leaseholder; the architect and builder was probably Thomas Martin (449, 478).Galinou discusses Tatham’s influence “in the early days of the St. John’s Wood estate” in chapters 3 and 8. Birnie was his neighbor, at 35 Alpha Road. Galinou reproduces an illustration of Tatham’s house (fig. 56, p. 118), which reveals that it was two floors with an attic and commanded a “vast expanse of ground” (158). It was not a small dwelling. The Tate’s description of Linnell’s watercolor Tatham’s Garden, Alpha Road, at Evening (illus. 1) gives an accurate idea of the size and grandeur of the “cottage,” though it supposes that Tatham, not Martin, was the architect: The scene is in the garden or grounds of Linnell’s friend Charles Heathcote Tatham’s house, 34 Alpha Cottages, Alpha Road, Marylebone, London. Alpha Road ran between Park Road and Lisson Grove, to the west of Regent’s Park. Houses on either side of it, designated Alpha Cottages, began to be built c. 1808 (the first year in which they were rated), in what had formerly been open fields. Charles Heathcote Tatham (1772–1842), at this period a flourishing architect with a practise in Queen Street, Mayfair, designed and built 34 Alpha Cottages for himself; but his house was no cottage in the ordinary sense. Marylebone Parish Rate Books (Marylebone Library, Archives Department) show that it had the highest rateable value in Alpha Road (£120 p.a.; most of the other houses were rated below £50); street plans show 34 Alpha Cottages as a sizable detached house, set at an oblique angle to the road in large grounds.“See R. Horwood, Plan of the Cities of London and Westminster, 3rd ed., 1813; Peter Potter, Map of the Parish of St. Marylebone, 2nd ed., c.1824. It should be noted that some renumbering of Alpha Cottages took place between 1812 and 1826, in the course of the development of the road, and possibly because one or more of its semi-detached houses came under single ownership; rate books at the beginning of that period number Tatham’s house first as 36, then as 35 and finally as 34. The street was styled Alpha Cottages until 1826, when it became known as Alpha Road” (The Tate Gallery 1984–86: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions Including Supplement to Catalogue of Acquisitions 1982–84 [London, 1988] 74-75, quoted at <http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/linnell-tathams-garden-alpha-road-at-evening-t04139>). The house was already renumbered 35 Alpha Road by 1824 (see Boyle’s Directory for 1824), and the location was already then known as Alpha Road.

© London Metropolitan Archives, City of London. SC/PM/LC/01/04/123.

C. H. Tatham also had a house at 1 Queen Street, Curzon Square, in Mayfair.Tatham Sr. was recorded in the Royal Blue Book for 1825 as “Charles Heathcote Tatham Esq., 1 Queen St., Mayfair, and 35 Alpha Road, Regents Park.” In Clayton’s Court Guide to the Environs of London, 1830, Frederick Tatham appears as “F. Tatham Esq., Alpha Road, Paddington.” Because all of Tatham’s correspondence with the Eyre estate went to this address until 1831, Galinou believes the house at “Alpha Road was a second residence (his main address being in Mayfair)” (478).Galinou notes that C. H. Tatham “may have relied on hackney coaches (the taxis of the day) or his own two feet for travelling back and forth, as he does not appear to have added stables and a coach house to the Alpha Road property” (251). However, the Alpha Road residence had a coach house and stables by 1828, and probably earlier (Marylebone Rate Books [hereafter MRB] 1828, reel 55). The house in Mayfair was rated at £66, however—about half that of the other houses on the street and half that of his “cottage.” It appears never to have been a family residence, since none of Tatham’s children was born there. His first child, Charles Howard, was born at Park Street, Mayfair, as was Frederick, his third child, in July 1805. This was the address C. H. Tatham recorded in the 1802 Royal Academy exhibition catalogue. His fourth child, Lydia, was born at York Place, Marylebone, as was his fifth, Arthur, in September 1808. He used the York Place address for the 1807 Royal Academy exhibition. He appears to have moved from York Place to Alpha Road by 1811. By 1809, while living at York Place, he began to use the 1 Queen Street house as his office and studio; he is listed there in the Royal Academy exhibitors’ catalogues from 1809 until 1831 (Graves, Royal Academy 7: 324-25).The Park Street and York Place residences appear to have been family residences as well. No births are recorded at the Queen Street address, suggesting it was used exclusively as his work space from 1809 onward. Frederick Tatham listed the same address for the Royal Academy exhibition in 1825 (Graves, Royal Academy 7: 325), for the British Institution exhibitions in 1828 and 1829 (Graves, British Institution 528), and for the Royal Society of British Artists in 1829 (Whitehead, “Last Years” 83). He used 20 Lisson Grove for the Royal Academy shows from 1830 to 1832.

Whitehead has reasonably proposed that Catherine lodged in rooms above the Mayfair office, rather than at Alpha Road, with Frederick Tatham spending weekends with his family and most weekdays in the studio in Mayfair, presumably one of the rooms upstairs, and thus a relatively limited amount of time with her (“Last Years” 82-83). Though smaller than neighboring houses, the Mayfair office was certainly large enough for a tenant and her belongings, which included a press and many copperplates. Tatham Sr. had known Catherine since at least 1799, when he acquired Blake’s America copy B (BB 100).On the verso of the frontispiece, Tatham inscribed: “From the author / to C H Tatham Octr. 7 /1799.” The signature matches those in letters C. H. Tatham wrote to Sir John Soane, which are in the Soane Museum. Blake owned copies of Tatham’s Three Designs for the National Monument (1802) and Etchings, Representing the Best Examples of Ancient Ornamental Architecture (1799[–1800]), neoclassical line drawings that Tatham had etched himself and that had become an important and influential sourcebook for architects and designers (BB 697).C. H. Tatham “spent two years working on the 102 plates showing the best examples from [Henry] Holland’s collection, and published in 1799 Etchings of ancient ornamental architecture drawn from the originals in Rome and other parts of Italy during the years 1795 and 1796. Of the 210 subscribers, almost a third were architects and craftsmen.” A second edition, containing more than 100 plates, appeared in 1803, and a German translation was published at Weimar in 1805. A third edition was published in London in 1810, and often reprinted. In 1806 Tatham published the companion Etchings Representing Fragments of Antique Grecian and Roman Architectural Ornament; in 1826 the two works were issued together (ODNB). On 15 March 1827, Blake wrote Linnell to tell him that he “saw Mr Tatham Senr yesterday he sat with me above an hour & lookd over the Dante he expressd himself very much pleasd with the designs as well as the Engravings” (E 782-83). The visit, which appears to have taken place at Fountain Court, is further testimony of C. H. Tatham’s regard for Blake. After Blake’s death, he appears to have been one of the “staunch friends like Mr. Richmond, Nollekens Smith and others” that Alexander Gilchrist claims wanted to help Mrs. Blake (1: 365).

C. H. Tatham, only fifty-six years old in 1828, would presumably have welcomed the opportunity to provide living and studio space to the widow of an old friend. And like his friend Linnell, he knew how to use and value a rolling press. He had been trained in drawing—and presumably etching—by the engraver John Landseer, and had been collecting prints since late 1796, after he returned from Rome and inherited “a valuable collection of prints.”A transcription of C. H. Tatham’s unpublished autobiography, written in 1826, is online at the Tatham Family History site. He was an active designer, still exhibiting at the Royal Academy (fifty-three designs between 1797 and 1836).C. H. Tatham did not exhibit in 1832, 1833, or 1834, for good reasons (see sections 9 and 10), but he returned in 1835 and again in 1836. At his Alpha Road home, he hosted many gatherings of artists; indeed, it had become “a focus of artistic activity” (ODNB). Blake met the sixteen-year-old Richmond at the Alpha Road home (A. Gilchrist 1: 297). Other visitors included Samuel Palmer, Edward Calvert, Benjamin Haydon, and possibly Welby Sherman, a member of the Ancients.Haydon boarded at the house of Tatham’s friend John Charles Felix Rossi at 21 Lisson Grove North, an adjacent neighborhood that Frederick Tatham would move to c. 1830. By 1817, Rossi’s prosperity had declined, and he rented rooms in his house to Haydon, who remained a tenant until 1822. Haydon executed a pastel portrait of C. H. Tatham in 1823 (said to be “remarkably similar to a painting ascribed to Linnell”) <http://www.saxonlodge.net/showmedia.php?mediaID=279&medialinkID=375>. Several of these, including Calvert and Sherman, were influenced by Blake to try their hands at engraving and wood engraving; in 1827, Richmond had engraved “The Shepherd” and “The Fatal Bellman.”

Catherine stayed in Mayfair for about a year, from April 1828 until late March or early April 1829. This is apparently where Frederick Tatham drew her portrait, which is dated “Septr. 1828” (illus. 5).

In effect, Frederick Tatham arranged for Catherine’s lodging rather than providing it. The person responsible for providing it was C. H. Tatham, who paid the rates where she appears to have resided. Frederick Tatham seems to have intentionally concealed the details of these arrangements, presumably because he wanted to appear as her only gracious benefactor; in his “Life of Blake,” he also conceals Linnell’s generosity in helping Catherine immediately after Blake’s death (BR[2] 495n). He has not been alone in omitting C. H. Tatham’s role in Blake’s biography. The 1896 DNB entry for Richmond records his meeting Blake at Linnell’s house, despite Gilchrist’s account. Richmond’s son, however, verified Gilchrist’s claim: “The home of Mr Tatham the architect, was a centre for the visits of remarkable men, and prominent among them was William Blake at the period when he was living at 3, Fountain Court. My father met him for the first time at Mr Tatham’s House in Alpha Road, St John’s Wood” (Stirling 24).Linnell introduced Richmond to C. H. Tatham as a potential drawing teacher for Tatham’s daughter Julia (whom Richmond married in January 1831). Linnell introduced Palmer to C. H. Tatham as well as to Frederick, who, like Richmond and Palmer, was then training to be a painter (in addition to being a sculptor). Nevertheless, the 2004 ODNB does not mention the place of their meeting. Tatham Sr.’s hand in helping Frederick Tatham help Catherine Blake appears to have gone unrecognized in modern Blake studies, except by Whitehead.

5. 1829: Catherine Blake Prints Copies of America and Europe in Mayfair after Moving to Her Apartment

Catherine Blake moved from Curzon Square to Fitzroy Square in early spring 1829, around the time she printed America copies N and Q and Europe copies I and L. These were probably the first posthumously printed relief-etched illuminated books, with one pair possibly commissioned and the other printed on speculation. They appear to have been printed after she moved to her apartment in Fitzroy Square. She presumably retained access to the studio and brought Blake’s other works—the drawings, manuscripts, paintings, sketches, and books—with her to the new apartment, where she set herself up as Blake’s agent and made “the occasional sale” (A. Gilchrist 1: 365). Crosby and Whitehead suspect that she also set up her press in her apartment and that she “had enough room here to print as well as colour and sell her husband’s works” (104; see also Whitehead, “Last Years” 89 and n137). The technical, material, and circumstantial evidence examined below suggests, however, that the press remained in Tatham’s Mayfair studio until the end of 1832 and that Catherine did not print any copies of Jerusalem or Songs. She did print two copies of America and two copies of Europe at Mayfair in spring 1829, which Tatham helped her sell, as is revealed by his letter of 11 April 1829. As noted, Tatham was responding to an inquiry that arrived shortly after Catherine left. The unknown person Tatham addresses had read in John Thomas Smith’s Nollekens that Catherine was alive, needed to sell copies of Blake’s books, and was doing so “at the original price of publication” (BR[2] 494-95, 626). Tatham replies: In behalf of the widow of the late William Blake, I have to inform you that her circumstances render her glad to embrace your Kind offer for the purchase of some of the works of her departed husband. … This elevated widow is now seeking a support during the remainder of her exemplary course, through the medium of the enlightened and the generous with no other hope than that she will ultimately be joined to that partner once more …. I can only add, that, should you, Sir, be inclined to possess, for the embellishment of your own collection, and the benefit of the widow, any of the enumerated works, they shall be carefully sent to you upon your remitting the payment, and I will take proper care that your Kindness shall be rewarded with the best impressions …. (BR[2] 495-96, emphasis added)

Tatham’s letter is known only as transcribed by Thomas Hartley Cromek in his “Recollections of Conversations with Mr. John Pye, London 1863–4” (BR[2] 871n37). Bentley suggests the engraver Pye may have been the recipient (BRS 90n178), but he also states that the recipient “may have been James Ferguson or the Earl of Egremont” (BR[2] 496). Both bought Blake works from Catherine around this time. Lord Egremont bought Blake’s painting of Spenser’s The Fairie Queene (Butlin #811), delivered that August; Ferguson bought illuminated books, presumably what Tatham meant by “impressions.” The letter was presumably the kind Tatham sent to Ferguson (and may have been the one he did send) and to other potential patrons. The phrase “enumerated works” implies an accompanying list; Tatham’s letter to Ferguson, which alluded to seven large color prints, included a “List of Works” (BR[2] 497, A. Gilchrist 2: 262).

According to Gilchrist, Ferguson (1791–1871) was “an artist … from Tynemouth” who wrote and “took copies of three or four of the Engraved Books” (1: 366). According to Bentley, Ferguson was in Tynemouth between 1824 and 1830, with a stay in London in 1827, though where in London and exactly when he does not say (“Peripatetic” 19). “In a List of Works by Blake, offered for sale by his widow, to Mr. Ferguson … occurs the following item:—A work called Outhoun. 12 Plates, 6 inches more or less. Price, £2 2s. 0d.” (A. Gilchrist 2: 262). The “List of Works,” like Ferguson’s letter, is not extant, nor is a work called Outhoun. Blake did, however, create a character named Oothoon, the main character of his Visions of the Daughters of Albion, apparently listed by Tatham from memory.Visions has eleven plates, though in his letter to Dawson Turner Blake advertised it as “folio” with “8” designs for £3.3s. (E 771). In his 1827 letter to Cumberland, Blake priced it at £5.5s. (E 784). Ferguson’s copy of Visions was in A. G. Dew-Smith’s collection that sold at Sotheby’s in 1878 (Viscomi, “Two Fake Blakes” 60). Dew-Smith of Cambridge or his agent may have acquired the work at the 1871 sale of the effects of Ferguson. Ferguson’s copy of Visions appears certainly to have been one of the three beautiful copies (N, O, and P) printed c. 1818, the last copies of Visions that Blake printed. The process of elimination indicates Ferguson acquired copy N because copies O and P had been sold by this time.Visions copy P, Thel copy N, and Marriage copy G were printed and finished in the same style and bound together; they were likely commissioned by an unknown collector and possibly initiated the c. 1818 printings of illuminated books (see BIB chapter 33). Visions copies O and N were printed on speculation, the former acquired by Crabb Robinson for £1.1s. (BB 477), presumably between 10 December 1825, when he met Blake (BR[2] 419), and August 1827, when Blake died.

Ferguson’s other “Engraved Books” almost certainly included America copy N and Europe copy I, both posthumously printed.America was initially designed as a monochrome work, with white-line hatching creating textures and tones; so, too, was its sister work, Europe, but the latter was finished in 1794, after Blake had begun printing his books in colors. Europe copy H is the only lifetime monochrome copy. Their owner, Sir George Grey (1799–1882), inscribed on the front flyleaf of America copy N:

I purchased this book at the sale of the

effects of a deceased artist, (I now forget his

name), who had obtained it direct from

Blake. The paper bears the paper mark

of 1812. This copy therefore although

purporting to be printed in 1793 and

1794—was probably printed after 1812, when

he was living in South Molton Street.Grey’s inscription is transcribed from a digital image of the flyleaf, as shown in the Auckland Libraries online digital gallery. There are three distinct passages on the flyleaf, and it is clear that Grey and subsequent owners and curators thought these copies of America and Europe were lifetime copies.

Although Grey clearly thought his copies were lifetime impressions, they came from Catherine, presumably through Ferguson, who died in Middleton-in-Teesdale (in the general vicinity of Grey, of Falloden, Northumberland) in 1871 (Bentley, “Peripatetic” 13). The sale to Ferguson of three “Engraved Books”—Visions, America, and Europe—was likely facilitated by Tatham, acting “in behalf” of Blake’s widow and rewarding patrons “with the best impressions.”

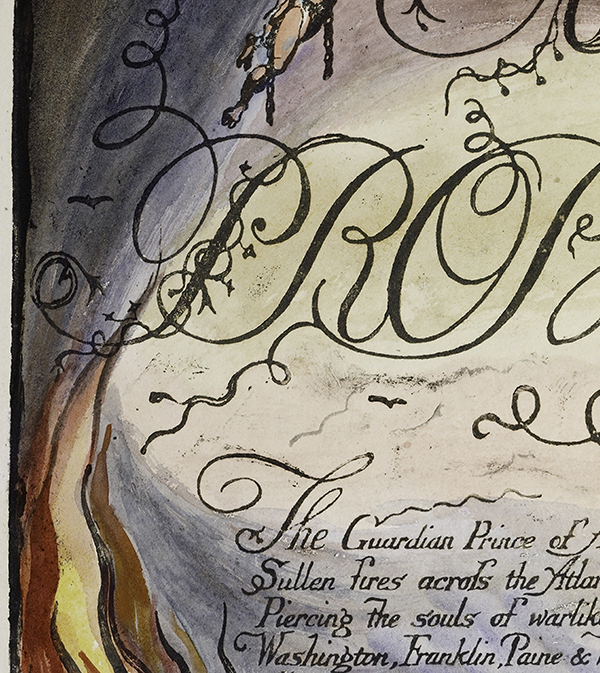

America copy N and Europe copy I were printed as a matching pair on the same size and type of laid paper in the same printing session and were similarly stabbed through three holes. They were produced with America copy Q and Europe copy L, which were also printed as a pair, though on wove paper (see below). For Catherine to print copies of America and Europe as matching pairs implies that one or both titles were no longer in stock. Both pairs were printed in black ink with full borders on quarto-size leaves: 32.6 x 23.6 cm. for America copy N and Europe copy I and 29.5 x 22.1 cm. for America copy Q and Europe copy L. Blake advertised America as folio in the 1793 prospectus and both America and Europe as folio in his 1818 letter to Dawson Turner (E 771), and all lifetime copies were printed with leaves that size—approximately 37 x 27 cm., which are quarters of imperial sheets. However, the last copies of America and Europe that Blake printed, copies O and K respectively, for Linnell in 1821, were 30 x 24 cm., closer in size to those printed by Catherine.

The paper and ink of America copies N and Q and Europe copies I and L are unlike the paper and ink used in the sixteen copies of four illuminated books printed on paper watermarked J Whatman / 1831 and J Whatman / 1832. Moreover, the copies with these J Whatman watermarks were all printed differently from the two pairs of America and Europe. The different materials and modes of printing point to different printers. First, consider the paper Catherine used. All eighteen leaves of America copy N and all seventeen leaves of Europe copy I are marked either R & T or ruse & turners / 1812 (BB 89, 142). The eighteen leaves of America copy Q and sixteen of the seventeen leaves of Europe copy L are marked either T Stains or T Stains / 1813 (BB 89, 142). Because printing papers did not come this size (Turner 209ff.), the leaves for both pairs of copies had to have been cut from larger sheets. For all but one of the leaves to be watermarked is unique among the illuminated books. Normally, an illuminated book has at most twenty-five percent of its leaves marked because Blake routinely produced his leaves by quartering large sheets. For example, America copy O and Europe copy K have thirty-six quarto-size leaves (trimmed to 30.3 x 24.0 cm.) of J Whatman / 1818, 1819, 1820 paper, but just ten watermarks, indicating that Blake probably quartered ten sheets of royal paper (approximately 63.5 x 50.8 cm.) to produce forty leaves. The ten copies of six illuminated books that Blake printed c. 1818 reveal the same pattern of paper preparation. The leaves in these copies, about twenty-five percent marked ruse & turners / 1815, appear to have been quarter sheets, with some quarters halved to produce the leaves for Songs copies T and U.The sheet size was possibly medium, approximately 58.4 x 45.7 cm. The leaves for Visions copies N, O, and P, Milton copy D, Marriage copy G, Urizen copy G, and Thel copies N and O were approximately 28 x 23 cm. untrimmed. That leaf size halved (or the sheet cut into eighths) produced leaves of 22 x 14 cm. for Songs copies T and U.

Catherine appears to have continued this practice when she prepared the leaves for For the Sexes copies F, G, H, and I, quartering eighteen or so super royal sheets of J Whatman / 1826. Blake had used J Whatman papers almost exclusively for books produced around and after 1818, which strongly suggests that these sheets were part of Blake’s stock, possibly acquired to print new copies of For the Sexes. The ruse & turners / 1812 and T Stains / 1813 papers were most likely not part of that stock. Blake never printed on T Stains papers, and the ruse & turners papers were laid, whereas Blake printed on wove paper (including the ruse & turners / 1815 paper used c. 1818)—and he emphasized that he did so in the 1793 prospectus.Blake wrote in his prospectus, “The Illuminated Books are Printed in Colours, and on the most beautiful wove paper that could be procured” (E 693). Before this, however, he printed Marriage copy L (plates 25-27, “A Song of Liberty”) on laid paper (with a C BALL watermark). This, the only illuminated book printed by Blake on laid paper, was etched in relief and printed c. 1790 in dark brown ink on a single sheet folded to make a pamphlet of two leaves, each leaf 21.2 x 17.3 cm., with plate 25 in the first of two states (see Viscomi, “Evolution,” 296 and n22). Nearly all the leaves are watermarked, indicating that the leaves of both stacks were almost certainly quarters cut from larger sheets. Catherine is very unlikely to have purchased from a stationer just the sections of the sheets with the visible watermark, or, for that matter, 1812 and 1813 paper c. 1829. Someone, perhaps C. H. Tatham, Frederick Tatham, or Linnell, may have given her remnants of sheets from his studio.The R & T and ruse & turners / 1812 papers are from different moulds and were possibly quarters of royal sheets (63.5 x 50.8 cm.); the T Stains and T Stains / 1813 papers are probably from the same mould, possibly medium sheets (58.4 x 45.7 cm.), with the date cut from the former. Both papers are thinner than the J Whatman Blake used more often. The marked quarters may have been set aside for aesthetic reasons because the marks were visible in wash and watercolor drawings—even without back lighting.

While the stacks of T Stains / 1813 and ruse & turners / 1812 papers were unlikely to have belonged to Blake, the leaves were prepared and printed in a manner that connects them to Blake and Mrs. Blake and differentiates them from impressions on the J Whatman / 1831 and 1832 papers. The 1812 and 1813 papers, like all of Blake’s papers, were printed damp. Consequently, lifetime impressions, which shrank upon drying, are slightly smaller than the impressions on J Whatman / 1831 and 1832 papers, which reveal no shrinkage in the image, making it clear that leaves were printed dry. The America and Europe impressions on T Stains / 1813 and ruse & turners / 1812 papers are the size of lifetime impressions and are consistently 2 to 4 or 5 mm. smaller than those printed in the copies of America and Europe on J Whatman / 1832 papers.Dampened papers, wove and laid, shrink about two to four percent. For example, the Experience title plate in Songs copies A, T, and AA is 12.5 x 7.2 cm. (left x top). In posthumous copies a and l, which were printed on heavy and thinner J Whatman paper respectively, it is 12.7 x 7.4 cm. (left x top). Larger images reveal the difference between plates printed on damp and dry paper more readily. For example, impressions of America plate 1 in copies F, H, and O range between 23.3 to 23.4 x 16.9 cm. (left x bottom); in America copy P, printed on J Whatman / 1832 paper, plate 1 is 23.9 x 17.3 cm. Europe plate 1 in proofs and in copies K and L ranges from 23.5 to 23.6 x 16.9 cm. (right x top); in Europe copy M, printed on J Whatman / 1832 paper, plate 1 is 23.9 x 17.2 cm. Jerusalem plate 45 in copy A is 22.55 x 16.25 cm. (right x top); in copy H, printed on J Whatman / 1831, it is 22.9 x 16.5 cm.

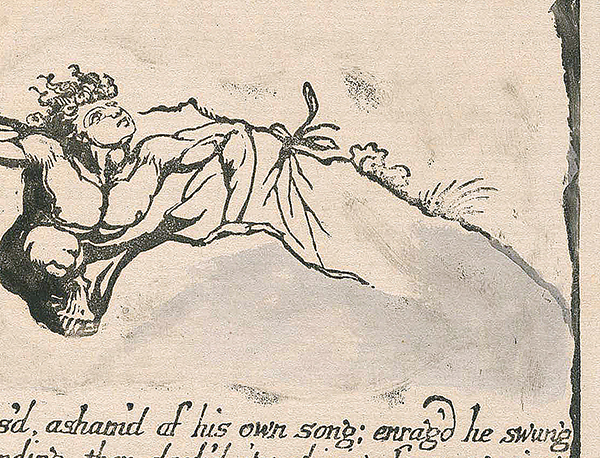

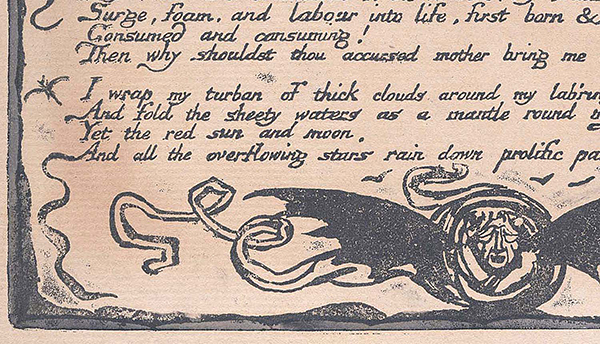

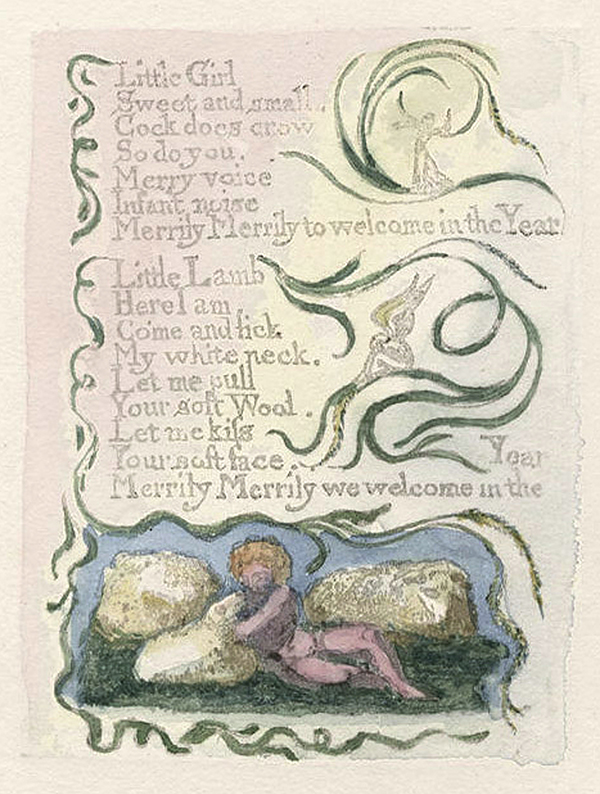

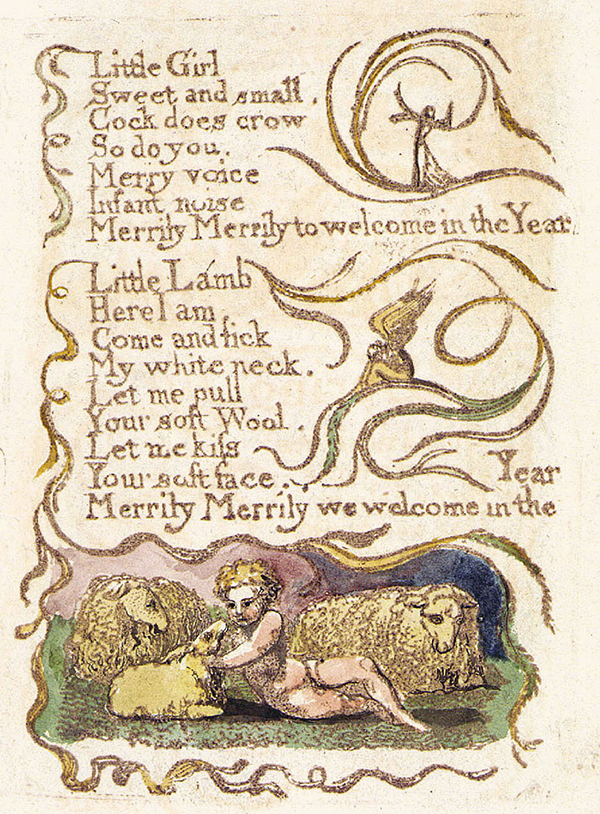

Catherine knew how Blake printed his books because she assisted him in printing them. Like Blake, she dampened the leaves for her copies of America and Europe. She also appears to have printed the plates in an intaglio ink. This is the kind of ink Blake used in illuminated printing, the sign of which is a more reticulated and less smooth or flat surface than is produced by relief ink (BIB 98-100). Reticulation, usually most noticeable in flat relief areas, can be obscured by washes. In monochrome works, such as Jerusalem copies A and F, America copies B and E, and Europe copy H, Blake brushed over the printed ink in black water-based washes, deepening the black outlines and plate borders and smoothing out splotchy areas. Catherine strengthened the plate borders in America copy N (illus. 8) and Europe copy I (illus. 9) in grey and black washes.

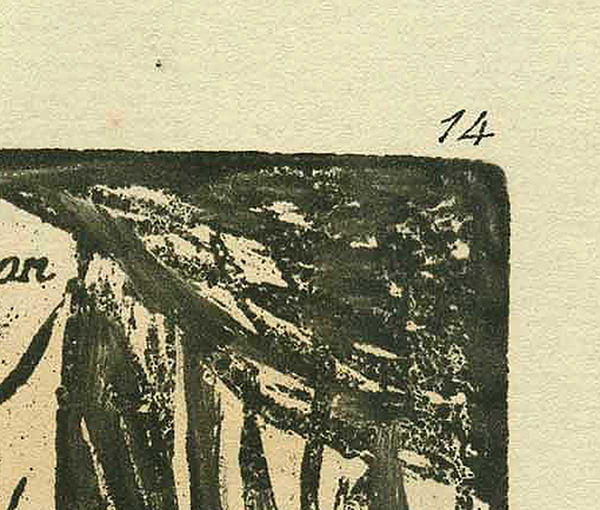

The numbers in black ink at the top right corner of the plates, where Blake usually placed his numbers, also appear to have been her work in all four copies. The number “14” on Europe copy I (illus. 12) is similar enough to the “14” in copy L (illus. 13), the posthumously colored copy, to strongly suggest one hand responsible for both.Bentley notes that the plate numbers in Europe copies I and L “have little authority” (BB 144n9). He also records, however, that their binding order is the same as Linnell’s Europe copy K (BB 146). As noted, Catherine may have had Linnell’s America copy O and Europe copy K—the last copies of these books that Blake printed—in mind when she printed her copies. The plate order in copy I, though, has a variant. The order of copy K is 1-5, 10, 9, 6-8, 11-18; it is the same in copy L (which is missing plate 3); in copy I (also missing plate 3), plate 5 follows 9. If the plate numbers in copies I and L are by Catherine, then copy I’s unique plate order was her doing. Europe copy M, printed by Tatham, follows the plate order of copies D, E, F, and G.

© Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. PD.127-1950(14).

Although Catherine printed America copy N and Europe copy I on laid paper and America copy Q and Europe copy L on wove paper, she appears to have printed the four copies in the same session. Printing books in different sizes in the same printing session is to print per copy rather than per plate. From 1789 through 1795, Blake printed per plate, which yields many impressions that are then compiled into copies (BIB 153-57). He began to print per copy after 1800, when he returned to printing a few copies of Innocence and Experience (BIB 377-78), often one copy by commission and another for stock. By printing leaves from different piles, he was able to create copies of the same book in different sizes during the same session. Blake appears to have used this method to print Songs copies W and Y at the same time on quarto and octavo leaves respectively.Calvert owned Songs copy Y, presumably ordering it directly from Blake; Catherine owned Songs copy W, presumably printed on speculation. That Visions copies N and O also sold long after they had been printed with copy P indicates that they were produced on speculation. The mode in which America copies N and Q and Europe copies I and L were produced suggests Catherine’s hand because it resembles what she and her husband had done previously. That they were printed in black intaglio ink on dampened paper and touched up in grey and black washes differentiates them from Jerusalem copies H, I, and J, America copy P, Europe copy M, Songs copies a, b, c, d, e, f/j, g, h, i, and p, and loose impressions, and Innocence copy T—that is, from all the books printed on J Whatman / 1831 and 1832 papers. These were printed in sepia, a hue never used by Blake, or black. These inks transferred more solidly because they were designed for relief rather than intaglio printing; they were not touched up with added washes; and they were printed on dry paper.

Catherine seems to have produced her copies of America and Europe to fill an order by Ferguson, probably in spring 1829, but no later than 1 August 1829, when her fortunes changed dramatically and removed the need for her to print copies of illuminated books (see below). At any rate, America copy N and Europe copy I were sold together, presumably with Visions copy N and apparently to Ferguson. The sister copies—America copy Q and Europe copy L—were probably printed on speculation. They appear to be the copies Palmer claimed belonged to Robert Peel (BB 105), whose brother-in-law, the Rev. Cockburn, lived in Frederick Tatham’s Lisson Grove neighborhood (though, as we will see in section 9, not as Tatham’s neighbor, pace Whitehead, “Last Years” 82n64).Rev. Cockburn married Elizabeth Peel, daughter of Sir Robert Peel and sister to Robert Peel, the future prime minister. According to The Records of the Cockburn Family, she “brought him some forty or fifty thousand pounds” (Cockburn and Cockburn 67). According to Galinou, Cockburn’s house, known as Lisson Lodge, was not listed among the Eyre developments, so it is probable that it was outside the Eyre estate (private correspondence). Tatham apparently made the sale, but whether he did so for himself or for Catherine is not known.

On 1 August 1829, Catherine delivered Blake’s large watercolor of Spenser’s The Faerie Queene to Lord Egremont (BR[2] 498), whose wife had much earlier commissioned The Vision of the Last Judgment and Satan Calling Up His Legions (Butlin #642, 662). Lord Egremont’s payment of £84 was probably enough “to have kept Catherine out of want for the rest of her life” (BR[2] 499). This was a goodly sum, considering that “Blake’s yearly income does not seem to have gone much above £100, and sometimes it was probably not much more than £50” (BR[2] 812). This gift, combined with the £20 she received in early 1829 from her brother-in-law Henry Banes (along with some furniture) and, as we will see, the monies she made from sales by the end of 1829, improved Catherine’s financial situation enough that she withdrew her application for assistance from the Artists’ General Benevolent Institution, 5 January 1830 (BR[2] 501-02). With “the widow of the late William Blake” now having some financial security, the incentive to print more monochrome copies of the books—which could earn at most only a pound or two (see section 12)—apparently disappeared. The first period of posthumous printing appears to have ended in spring 1829, but no later than midsummer 1829, by which time Catherine produced four copies of For the Sexes (F-I), two copies of America (N and Q), two copies of Europe (I and L), a few impressions of “Canterbury Pilgrims” and the Dante engravings, and at least single impressions (though possibly more) from “Joseph of Arimathea,” “The Interpreter’s Parlour,” and the Rev. Hawker portrait.

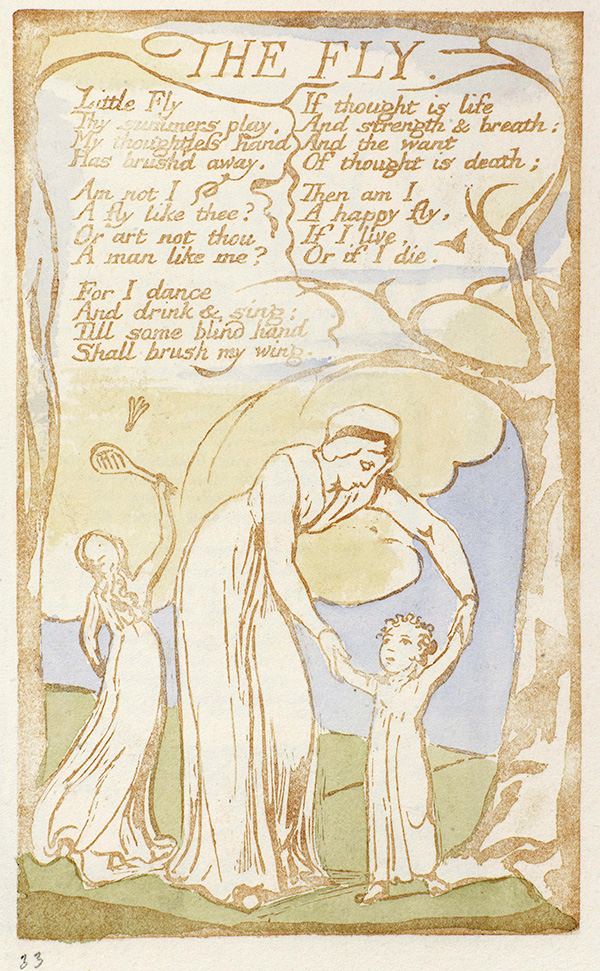

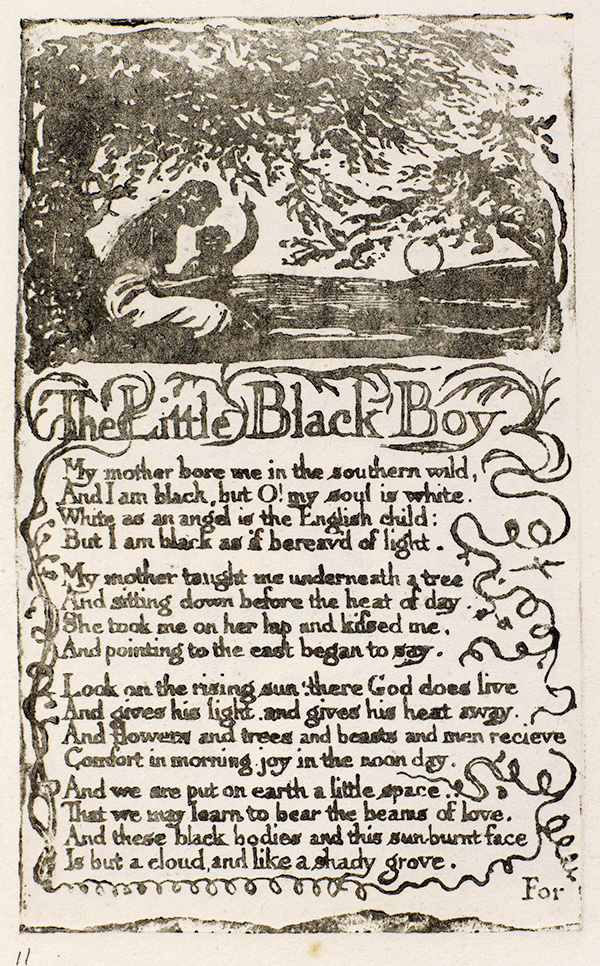

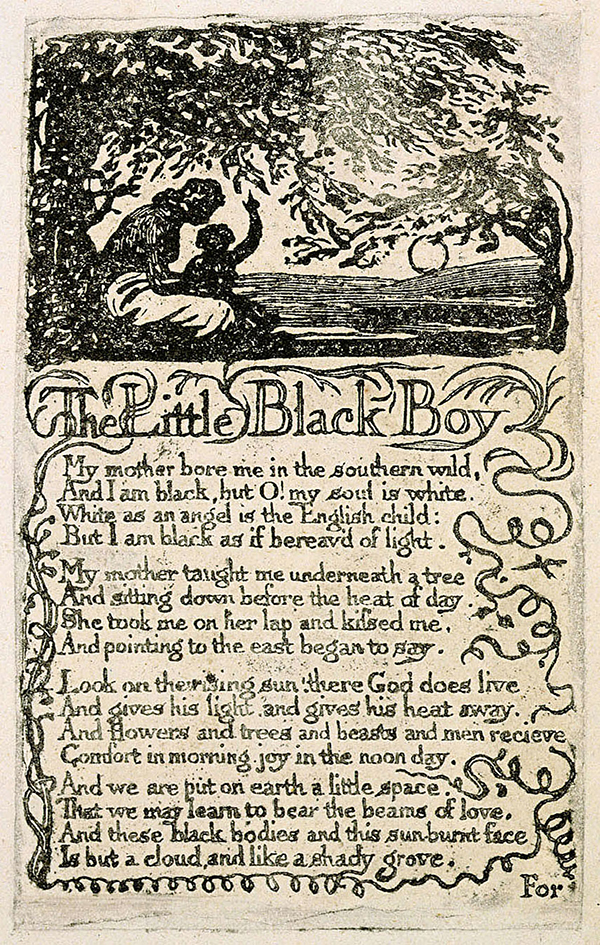

6. 1831–32: Frederick Tatham Prints Illuminated Books in the Mayfair Studio