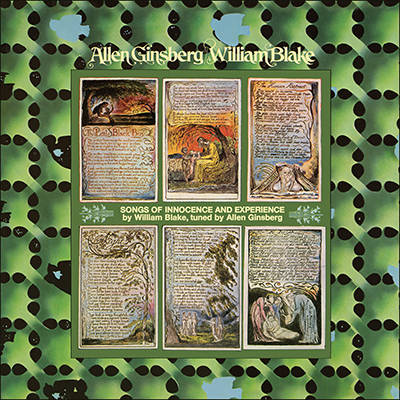

There are several reasons why this 2017 album release represents a significant moment for anyone interested in the role played by William Blake in shaping the counterculture of the sixties (and the role of that counterculture in shaping academic and popular understandings of Blake). The most basic is that the original 1970 album, Songs of Innocence and Experience [sic] by William Blake, Tuned by Allen Ginsberg, has never previously been made available as a CD or digital download. However, it is a credit to Pat Thomas, who produced this expanded reissue for Omnivore Recordings, that there are other, more important, reasons to celebrate. The double-CD Complete Songs of Innocence and Experience is not just a rerelease of the album in a new format with a few alternative takes added as filler; rather, at over twice the length, it aims for the first time to fulfill Ginsberg’s original intentions for his extensive Blake recording project, to which he devoted much of his creative energy between 1968 and 1971.With the blessing of the Ginsberg estate, the 1970 album continues to be freely available to stream from the University of Pennsylvania’s PennSound website, as it has been for the last decade or so: <http://writing.upenn.edu/pennsound/x/Ginsberg-Blake.php>.

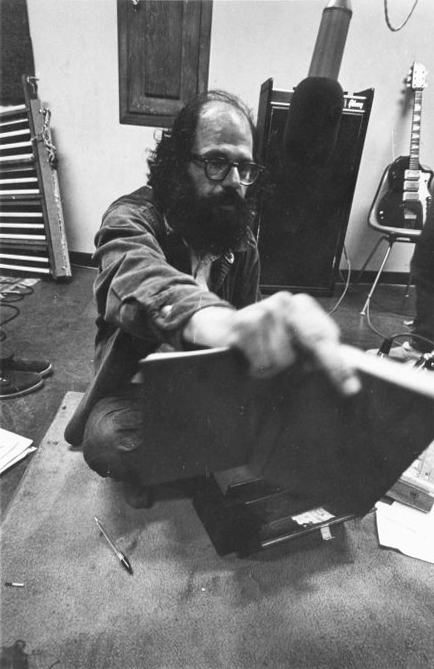

As might be expected from a package such as this, the CD booklet contains abundant background information on the recording sessions of 1969 and 1971, including details of the impressive (if eclectic) roll call of musicians whom Ginsberg persuaded to work with him. The booklet concludes by quoting the beginning of Ginsberg’s fascinating essay “To Young or Old Listeners: Setting Blake’s Songs to Music, and a Commentary on the Songs,” which formed the liner notes to the original album and was also printed in the winter 1971 issue of this journal.Allen Ginsberg, “To Young or Old Listeners,” Blake 4.3 (winter 1971): 98-103. As he reminds us there, his personal connection to several of the songs had begun two decades earlier, with his famous vision of 1948, when “in mind’s outer ear I heard Blake’s voice pronounce [Ah!] Sun Flower and The Sick Rose … and experienced an illumination of eternal Consciousness.” With suitably Blakean emphasis, he describes how “after 20 summers musings over the rhythms,” during which he lived through the “Apocalyptic history” of the Beat fifties and countercultural sixties, he had eventually “imagined this music” into existence.

While the roots of the Blake recording project were personal and visionary, the more immediate inspiration was political. This explains the anomalous presence of “The Grey Monk” within an album devoted to Blake’s Songs; recognizing the appropriateness of the poem’s theme to the political situation of the late sixties (“But vain the Sword & vain the Bow / They never can work Wars overthrow”), Ginsberg had sung this poem during the tumultuous event that he epigrammatically refers to in his Blake essay as “Democratic Convention 1968 Tear Gas Chicago.” As the tension in Chicago began to build up to the climactic police riot, he sat cross-legged on an outdoor stage, accompanying himself on his Indian harmonium as he sang “The Grey Monk” and Hindu mantras. This was his first musical performance of Blake’s poetry, and it directly inspired him to begin setting the Songs themselves to music. The songs released on the 1970 album represented the first fruits of this labor, and these, along with two previously unreleased tracks from the same session, make up the first CD of The Complete Songs. But as he had promised in “To Young or Old Listeners,” Ginsberg continued to “tune” Blake’s songs over the next few years, and organized a second series of recording sessions in the summer of 1971, accompanied by a new group of musicians, which notably included the avant-garde cellist Arthur Russell.The guitarist Jon Sholle was the only accompanying musician to play on both the 1969 and 1971 sessions. These 1971 sessions unfortunately never led to the envisaged second Blake LP, even though, as Barry Miles notes in the CD booklet, “Allen had learned a lot from the 1969 recordings … had performed the songs live onstage for two years and also learned better microphone technique.” Eleven Blake songs from these later sessions are now included on the second disc, so that the expanded album, though not quite truly “complete,” finally contains an impressive total of thirty-one of the Songs, plus “Let the Brothels of Paris be opened” and two versions of “The Grey Monk” (one featuring appropriately martial drums and one a newly discovered, stripped-back version as Ginsberg had originally performed it in Chicago).

It may seem conceptually inconsistent to some listeners that after “The Voice of the Ancient Bard,” the second disc concludes with over twenty minutes of Buddhist and Hindu mantras, which Ginsberg and the musicians had also recorded during the 1971 sessions. Before considering the artistic and interpretative merits of The Complete Songs, I want to address this aspect of the album by suggesting that in the context of the Ginsberg-Blake connection—itself a central strand of Blake’s broader sixties reception—these additions are far from incongruous. Among Ginsberg scholars, it has sometimes been suggested that Buddhism competed with Blake for Ginsberg’s attention, with his 1963 poem “The Change” typically interpreted as marking the beginning of that shift in allegiance; my own research suggests, however, that while Ginsberg’s deepening commitment to Buddhism in the sixties and seventies helped him to overcome a problematic fixation with the 1948 Blake vision, it also coincided with (and even influenced) his growing intellectual involvement with Blake’s poetry, including a strong engagement with contemporary and historical Blake scholarship.See Luke Walker, “Allen Ginsberg’s Blakean Albion,” Comparative American Studies 11.3 (2013): 227-42.

As Ginsberg admits at the beginning of “To Young or Old Listeners,” his familiarity with Blake at the time of his vision, and for some time thereafter, had been at best “fragmentary.” But the resumed Blake recording sessions of the early seventies coincided not only with his decision to take formal vows of refuge in Tibetan Buddhism, but also with an acceleration of his reading as he prepared to teach a series of literature classes on Blake. Fascinating insights into the range and depth of Ginsberg’s engagement with Blake in this period can be found in several of his distinctive to-do list poems. Thus, in “What I’d Like to Do” (1973), he urges himself to “study prophetic Books interpret Blake unify Vision”; he hopes this will provide the “Inspiration” necessary to “compose English Apocalypse … Tibetan mantra Blues” and also to extend further the Blake recording project: “Compose last choirs of Innocence & Experience, set music to tongues of Rossetti Mss. orchestrate Jerusalem’s quatrains.”Allen Ginsberg, Collected Poems, 1947–1997 (New York: HarperCollins, 2006) 610. After the 1971 sessions, a handful of Blake’s Songs still remained to be “tuned,” but no further Blake recording sessions took place. Ginsberg did, however, continue to perform his Blake settings live, and also initiated various subsequent (non-Blakean) musical projects, including collaborations with Bob Dylan and the Clash. Similar concerns, as well as evidence of his reading of secondary literature on Blake, can be found in his 1978 poem “All the Things I’ve Got to Do.” Here, among a great variety of unfinished projects and chores—poetic, political, spiritual, and domestic—Ginsberg reminds himself to read “David Erdman’s Symmetries of the Song of Los / a paper on my bookshelf a year” and to “xerox my Blake music sheets.”Allen Ginsberg, Wait Till I’m Dead: Poems Uncollected, ed. Bill Morgan (London: Penguin, 2016) 134-35. It may have been sitting on his “bookshelf a year,” but Erdman’s essay had only been published the year before (in Studies in Romanticism), so Ginsberg was actually remarkably up to date with his Blake scholarship.

Before offering an analysis of the recordings themselves, I want to draw attention to Morris Eaves’s insightful and open-minded review of the original album, which appeared in the same 1971 issue of this journal that contained Ginsberg’s own essay. Eaves notes that Ginsberg and especially his life-partner, Peter Orlovsky, who contributed vocals to some of the songs, possess “outrageous voices”; indeed, “Ginsberg and company demand of the listener a child’s indifference to conventional musical values.” Despite this (or even because of it), Eaves is ultimately hugely sympathetic to the album, concluding that “Ginsberg’s compositions are the best of any yet written for Blake,” although he fears that “few will think so.”Morris Eaves, rev. of Allen Ginsberg, Songs of Innocence and Experience by William Blake, Tuned by Allen Ginsberg, Blake 4.3 (winter 1971): 90-97.

As Eaves suggests, much of the power of this music comes from its heartfelt sense of purpose and the deep love of Blake that it reveals. However, now that we can finally also hear the richer, subtler, and more harmonious 1971 recordings on the second disc of The Complete Songs, it is obvious that Ginsberg gained the ability to create much more polished music, without sacrificing any of the Blakean innocence of the 1969 sessions. As such, these later recordings throw into relief the faults as well as the successes of the original album. In the context of this much-expanded and improved body of work, it no longer seems necessary to defend several rather painful tracks on the original, such as “The Chimney Sweeper” and “Holy Thursday” (Innocence), even if Ginsberg himself insisted that the jarring sound of the latter was deliberate: “Spaced out Orlovsky singing against Don Cherry on Flute and trumpet Zapped the tune up to ecstatic joy instead of a tender lamblike chorus.”Ginsberg, “To Young or Old Listeners” 101. (A few of Orlovsky’s vocal contributions, such as on “Night,” are more harmonious, but it is hard not to conclude that the 1971 sessions are improved by his absence.)

The opening track of the second disc, “A Cradle Song,” immediately reveals a wholly different sound and technique, as Ginsberg’s newly open, tuneful singing voice emerges, accompanied by the cello and flute. Similarly, on tracks such as “Spring” and “Infant Joy,” he creates a beautifully balanced state of joyous innocence. Although Eaves is surely correct to argue that the original album aims to immerse the listener in a state of Blakean innocence that transcends intellectual criticism, it is here on these simplest of Blake’s lyrics that the interpretative potential of this technique is fully realized, with a sound and a subtlety that are quite different from the early sessions. Meanwhile, on 1971 recordings like “The Divine Image,” Ginsberg adopts the same simple technique that he had earlier used on “The Sick Rose” and “The Human Abstract,” chanting solo against the insistent drone of his Indian harmonium. While these represent some of the best songs on the original album, “The Divine Image” shows that this Indian sound can also work very well with a more open singing voice.

Overall, the additional tracks on The Complete Songs add enormously to the enjoyment of Ginsberg’s Blake album, as well as emphasizing the way in which he employed a wide variety of techniques and influences in his settings of Blake, both during the original 1969 sessions and later. Referring to Ginsberg’s hope “that musical articulation of Blake’s poetry will be heard by the Pop Rock Music Mass Media Electronic Illumination Democratic Ear” and his linking of Blake (and himself) to Bob Dylan and other well-known musicians of the period, Eaves suggests that “Ginsberg’s own music resembles none of the musicians he names so much as it does the Incredible String Band.”Eaves 92. This is indeed an apt comparison, and it comes as little surprise to read in Joe Boyd’s recent memoir that this psychedelic folk group were themselves strongly influenced by Blake’s poetry.Joe Boyd, White Bicycles: Making Music in the 1960s (London: Serpent’s Tail, 2007) 121-23. However, a range of other influences and similarities can indeed be heard in Ginsberg’s music; together, these illuminate and contribute to Blake’s sixties identity. Thus, as Eaves points out, on “The Blossom” Ginsberg and the musicians create an impressively natural and unforced approximation of the music of Blake’s own period (or perhaps earlier). Elsewhere, on both discs of the expanded album, Ginsberg makes deliberate use of various atonal or microtonal settings that extend beyond the use of his Indian harmonium and are sometimes reminiscent of the avant-garde music of the Velvet Underground. I am thinking particularly of the unusual sound texture achieved on “The Little Black Boy,” which Eaves hesitatingly describes as “sort of oriental.”

Perhaps most importantly, the claimed link to Dylan should not be dismissed, although as always with the Blake-Dylan-Beat connection, the dynamics of these “relationships of ownership” (to borrow a phrase from Dylan’s Blakean song “Gates of Eden”) are more complicated than they at first appear. Part of Ginsberg’s impetus for setting the Songs to music had been to encourage Dylan’s interest in Blake, and Dylan later included footage of Ginsberg singing “Nurse’s Song” (Innocence) in his epic experimental film Renaldo and Clara (1978).See Luke Walker, “Tangled Up in Blake: The Triangular Relationship among Dylan, Blake, and the Beats,” Rock and Romanticism: Blake, Wordsworth, and Rock from Dylan to U2, ed. James Rovira (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2018) 1-18. Meanwhile, the elements of Dylan’s oeuvre that seem to chime most directly with Ginsberg’s Blake are those associated with his late-sixties recordings. Ginsberg’s settings of “The Garden of Love” on the first disc and “Holy Thursday” (Experience) on the second include country elements that are somewhat reminiscent of Dylan’s John Wesley Harding (1967) and Nashville Skyline (1969); however, a sound and more especially a sensibility are found throughout Ginsberg’s Blake recordings that particularly bring to mind Dylan’s 1967 Basement Tapes sessions with the Band (released in 2014 as The Bootleg Series, Vol. 11). As Greil Marcus masterfully demonstrates in his book on the Basement Tapes, the power of these Dylan sessions comes from the way they link the late-sixties moment to specific periods and places in American history, and ultimately to a substratum of myth and archetype.Greil Marcus, Invisible Republic: Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1997), later revised as The Old, Weird America: The World of Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes (2011). I want to suggest firstly that this weaving of place, myth, and history can be aligned to Blake’s own mythopoeic method, and secondly that through his Blake recordings, Ginsberg similarly weaves Blake into the “Apocalyptic history” of the sixties.

This is a mythic version of the present that Ginsberg views through Blakean eyes; throughout “To Young or Old Listeners,” he displays a particular interest in Gnosticism, which in Blakean fashion he links to the historical particularities of the present day. Thus, his lengthy notes on “To Tirzah” (one of the best songs of the original album) begin by describing Blake’s text as a “late wisdom, Gnostic-Kabalistic-Buddhist transcendental put-down of the entire phenomenal sensory universe as a mental Illusion,” but go on to relate Gnostic myth (and the history of the early Christian church) to the politics of the late sixties: “The Roman State coopted religion at Council of Nicea & … established the Satanic State, presidently headed by Richard Nixon, Jehovah in disguise forgetting to whom he is beholden … only a flash of Sophia’s Consciousness.”

Ginsberg’s intention, when “tuning” the Songs, to evoke the Blakean connections between hermetic tradition and the apocalyptic politics of the 1790s and 1960s also forms the main topic of an interview for Partisan Review, conducted as he was preparing to record the 1971 sessions.Allen Ginsberg, Spontaneous Mind: Selected Interviews, 1958–1996, ed. David Carter (New York: HarperCollins, 2001) 259-72. His first Blake settings had sprung “from the ashes of the body of American democracy in Chicago,” while his recent setting of “The School Boy” had been inspired by the news of the massacre of protesting students at Kent State in May 1970. Ginsberg describes meditating until “Blake’s gnostic transcendental psychedelic inner glow comes on,” bringing with it an awareness “that the poems have a particular reference, a little hermetic sometimes, to any time-space continuum, to any political event.” Blake’s “The School Boy,” Ginsberg now realized, “appeals to certain emotional softnesses and tendernesses and innocencies which are completely repressed in the revolutionary-counterrevolutionary battle.” For him, as for Blake, the personal, the political, and the spiritual are inseparable, and these comments on “The School Boy” are immediately followed by an explication of the ancestral connections between different religious traditions that he sees as embodied in Blake: “He’s an eighteenth-century vehicle for Western gnostic tradition that historically you can trace back to the same roots, same cities, same geography, same mushrooms, that gave rise to the Aryan, Zoroastrian, Manichaean pre-Hindu yogas.” This, Ginsberg explains, is why it is not at all incongruous to describe Blake as his “guru.”

Finally, therefore, Ginsberg’s album is valuable as more than simply a historical artifact of the sixties’ countercultural Blake; Eaves’s brave conclusion—“Ginsberg’s music and Blake’s Songs possess corresponding powers”—has stood the test of time. I am confident that, with the revelatory addition of the second disc of songs from the 1971 sessions, The Complete Songs of Innocence and Experience will enable many more listeners to agree.