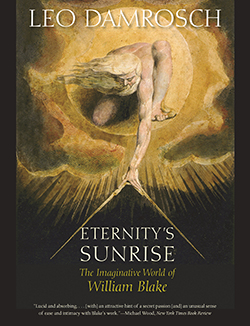

If you are a regular reader of Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, there is a good chance that you have friends who are somewhat mystified by your interest in William Blake. Leo Damrosch’s Eternity’s Sunrise: The Imaginative World of William Blake is a good way to explain that interest. As Damrosch puts it, “This book draws constantly on their [Blake specialists’] insights but is intended for everyone who is attracted to Blake and would like to know more about his art and ideas” (2). His “goal is to help nonspecialists appreciate Blake’s profoundly original vision and to open ‘the doors of perception’ to the symbols in which he conveyed it” (3). Eternity’s Sunrise is almost a coffee-table book, generously illustrated with forty color plates and fifty-six black-and-white images. There are also a brief chronology and a small black-and-white map of Blake’s London. Damrosch says that his book “has a strongly biographical focus, but it is not a systematic biography” (3); of the fifteen relatively brief chapters, the first eleven follow the progress of Blake’s life and career in a way that introduces the nonspecialist to Blake’s methods and themes, the following three address Blake’s attitudes toward gender and religion, and the final chapter returns to biographical chronology and the end of Blake’s life. Damrosch’s style leads the relatively uninitiated reader gently through Blake’s sometimes baffling world, but those working in Blake studies might wish for something more challenging.

The nonspecialist will find much to like in Eternity’s Sunrise. The book’s opening chapter presents introductory material on Blake’s early life and training, his apprenticeship, the difference between engraving and etching, Blake’s marriage to Catherine Boucher, and his discovery of relief etching (inspired by his dead brother Robert). In the second chapter’s helpful discussion of “How Should We Understand Blake’s Symbols?” Damrosch demonstrates Blake’s use of symbolism by showing how he adds his own symbols to his illustrations of the work of other writers, including Thomas Gray’s Eton College ode, Shakespeare’s “pity” speech from Macbeth, and the “sunshine holiday” episode in Milton’s L’Allegro. When Damrosch turns to Blake’s own poetry, his approach is both less systematic and more narrowly focused. Chapters 3 and 4 look at Innocence (mostly in the Songs of Innocence) and Experience (mostly in the Songs of Experience), but without much sense of the breadth of those books or of how they interact in the combined Songs. Chapter 5 looks at “Revolution” in the image “Albion Rose,” The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, and America, with a brief glance at Europe. Chapter 6, “Atoms and Visionary Insight,” describes Blake’s response to the Enlightenment, focusing on “Mock On Mock On” and Blake’s color print of Newton. Chapter 7, “‘The Gate Is Open,’” finds Blake already in Felpham (1800–03) and focuses on the work produced or at least begun during that period. In chapter 8 Damrosch considers “Understanding Blake’s Myth” before proceeding to discussions of the Zoas (chapter 9, “The Zoas and Ourselves”), Milton (chapter 10, “The Prophetic Call”), and Jerusalem (chapter 11, “Breakthrough to Apocalypse”).

Chapter 12, “‘The Torments of Love and Jealousy,’” backtracks twenty-seven years to Visions of the Daughters of Albion of 1793, and Damrosch recounts the well-known stories about the Blakes—Thomas Butts catching them reading Paradise Lost naked and Blake’s ill-tempered insistence that Catherine apologize to Robert—as a context for the sexual trauma of Oothoon. However, there is no discussion of either the slave trade, which the poem openly criticizes, or John Locke, whose Essay concerning Human Understanding informs much of Oothoon’s critique of sexual and moral standards. In chapter 13, “The Female Will,” Damrosch switches from Visions to For Children: The Gates of Paradise and “To Tirzah” (from Experience) and traces the stages in Blake’s attitude toward women and sexuality from Oothoon’s vision of sexual liberation to Vala’s cult of virginity, concluding that “even if [Blake’s] fears and obsessions [about sexuality] did damage the integrity of his imaginative work, he could never have created [that work] without them” (224). After some brief remarks on All Religions Are One, chapter 14, “Wrestling with God,” finally addresses Urizen, relating it to “The Ancient of Days” picture; Damrosch says much about what Urizen represents, but almost nothing about what actually happens in the poem. Chapter 15, “The Traveler in the Evening,” returns to chronology and considers Blake’s late poverty, his growing ambivalence about his audience (suggested by the gouges in Jerusalem plate 3), and the “Ancients,” the circle of young artists who befriended Blake late in his life.

Damrosch’s approach yields some very good summary statements about Blake’s work: his “imagination was fundamentally visual and … by learning to ‘read’ the images that accompany his words, we can gain access to the heart of his vision” (39); “For Blake personification was no mere rhetorical device; it expressed his belief that nature is fundamentally human” (41); “America: A Prophecy is prophetic in the sense already explained, a commentary on the meaning of events, not a prediction of the future” (104). He cautions that “Blake’s symbols are dynamic, not iconic. We learn what they mean by observing what they do” (114). On Blake’s attitude toward nature, which differs greatly from Wordsworth’s, Damrosch notes that Blake “had no use whatever for the sentimental ideal of Mother Nature” (213), but that “a case can be made that when Blake seems to criticize nature, his real target is often mistaken human constructions of nature” (232). He also recognizes something that perhaps many readers see but notice not: “After the Songs of Innocence, Jesus all but disappeared from Blake’s poems for nearly a decade” (255). I, for one, would certainly like to hear more about what Damrosch makes of this last fact.

Blake’s attitude toward religion is apt to give the nonspecialist the most trouble, and Damrosch does not shy away from that aspect of Blake’s work, nor from the relationship Blake saw between religion and gender. He notes that “Blake despised the theological doctrine that Mary was a virgin, and liked to suggest that if Joseph didn’t get her pregnant, somebody else must have” (56). He recognizes that “Blake was just as fierce a critic of institutional religion as Hume” (48), that “Blake rejected the concept of original sin” (70), and that “institutional religion, Blake thought, had a wicked commitment to promoting sexual repression” (73). Even so, he adds, “It needs always to be emphasized that Blake’s attack is not just on doctrine as abstract theology, but on doctrine as a mechanism for ratifying injustice” (245). Much of Blake’s attack on religious doctrine is related specifically to issues of sexuality and gender roles, and Damrosch is correct to be cautious about Blake’s approach to these issues late in his career. Particularly in the late major prophecies, Damrosch says, “Blake is preoccupied with an alleged domination of the female principle over the male” (218), and “Collectively, Vala and Tirzah represent a force that Blake insists on calling the Female Will” (221). That phrase “insists on calling” voices the frustration many readers feel about Blake’s handling of female characters, and Damrosch correctly notes that “Blake is not really a prophet of unconflicted sexuality, and his vision is closer to the tragic one that Freud expresses: ‘Something in the nature of the sexual instinct itself is unfavourable to the achievement of absolute gratification’” (211).

He also weighs in on the question of Blake’s mental health, saying at the outset, “It is important to recognize that Blake was a troubled spirit, subject to deep psychic stresses, with what we would now call paranoid and schizoid tendencies that were sometimes overwhelming” (2), and reiterating later, “It is hard to doubt that deep psychic disturbances do indeed lie at the heart of [Blake’s] work” (133). Most of Damrosch’s remarks come in the discussion of Blake’s three-year stint under the patronage of William Hayley in Felpham, a time of particular emotional turmoil for Blake, but he notes that “even before going to Felpham, Blake was afflicted with what was then called melancholy, and would now be called clinical depression” (133). In Felpham, “whether or not there was an element of bipolar disorder, Blake also experienced phenomena that would now be called schizoid” (134). Of the apocalyptic scenes of the books that arose from the Felpham period, Damrosch notes as “worth pondering” remarks by Ronald Britton “that a dread of psychic fragmentation and of the void is characteristic of borderline personalities” and “that Blake’s apocalyptic breakthrough can be seen as compensatory fantasy: ‘He unashamedly propounds as the route to salvation what in psychoanalysis has been called infantile megalomania’” (187-88). There is ample room for disagreement about Blake’s mental health, but whatever one thinks about it, Damrosch is certainly correct that Blake’s “myth also contains profound insights into the divided self, a condition that many people experience to some extent and that Blake experienced to a terrifying degree” (224).

Many of the things Damrosch does to accommodate the uninitiated reader may be annoying to the specialist. For example, while his first eleven chapters lead the reader through the general contours of Blake’s life and development, in chapters 7-11 we arrive at discussions of Felpham and the great final prophecies having had little comment on Europe, none whatever on Visions, The Song of Los, The Book of Ahania, or The Book of Los, and only passing mention of The [First] Book of Urizen. The more important of these books are discussed in the concluding chapters that are more thematic than chronological in nature. I’m not sure what is gained by this arrangement, and one might argue that it obscures key elements in the development of Blake’s work, while also tending to make his thought appear less dynamic over his lifetime. Damrosch also “corrects” Blake’s spelling and punctuation, a decision that some might argue removes a key component of the strangeness that makes Blake Blake. Stylistically, perhaps in an attempt to make the book more accessible, Damrosch has a tendency not to name critics in the text proper, so that if the reader wants to know, for example, who is the “modern expert on prints” who comments on the inverse relationship between the complexity of “the technique of a print” and the creativity of the engraver (32), one must turn to the endnotes, only to find “Ivins, How Prints Look, 158” (282). Since this is the second reference to Ivins’s book, and there is no central bibliography, nor is Ivins included in the index, the reader must then backtrack through the notes to find the publishing information. There is little discussion of the difference between illustration and illumination, or of the fact that many images in Blake’s texts seem entirely unrelated to what the words are saying. The closest Damrosch gets to those issues is to note, concerning “The Blossom,” “It may seem surprising that neither bird [sparrow or robin] actually appears in the picture, but it is characteristic of Blake to emphasize symbolic significance, not literal imagery” (58).

It is perhaps inevitable that Damrosch’s broad statements for the nonspecialist create a tendency to simplify explanations, gloss over real critical sticking points, and discuss characters as static entities. For example, concerning the Songs of Innocence, he writes, “Since the poems express multiple facets of Innocence, there is no correct order in which to read them” (57), but this statement ignores the complex history of the book’s production, its many different orderings, and the issues of “contexture” raised by critics like Neil Fraistat, not to mention Blake’s own delineation of “The Order in which the Songs of Innocence & of Experience ought to be paged & placed” in his letter to Butts of around 1818 (Erdman 772). Similarly, Damrosch reiterates the standard line on the major prophecies without acknowledging critical alternatives: “Blake’s long prophecies used to be called epics, but that makes no sense. An epic is a narrative based on strict chronology. … Blake has no interest in conventional continuity, and in his poems multiple versions of the ‘same’ events occur over and over again” (143). In remarking on the final image of Jerusalem, he suggests that “the divided selves of Los are reunited at last, and fully cooperative. But how this has come to pass is never shown or explained” (192), effectively ignoring the awakening of Albion in the closing plates of the poem. Concerning Visions he flattens the characters till they are hardly characters at all: “Since these are not novelistic characters but symbolic ones, it makes sense to think of them as conflicting aspects of human consciousness” (203). If you know little about Blake, these issues will pass relatively unnoticed, but if you are familiar with Blake’s work and Blake criticism, you may experience some frustration.

In his discussion of Milton, Damrosch says, “Since it is Blake in Felpham who has summoned Milton back to earth, a crucial event in the poem is their direct encounter. It is described, however, in imagery of surpassing weirdness” (167). Damrosch’s goal in Eternity’s Sunrise is to help make Blake’s “surpassing weirdness” accessible to the reader who has little or no formal background in Blake’s work. Writers like Blake, Joyce, or Faulkner can be intimidating and difficult to approach, but a little gentle guidance can go a long way to ease that first contact. For someone wondering what all the hubbub is about concerning Blake, Damrosch’s book may be just the thing.