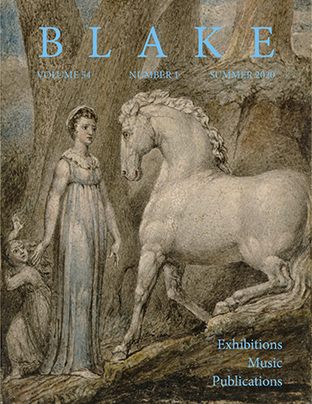

Blake and Exhibitions, 2019

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.47761/biq.262Abstract

2019 was an extraordinary year for Blake. The retrospective at Tate Britain reassessed his work in the context of the choices that shaped the making of an artist’s career in Romantic-period London; elsewhere, individual works were reinterpreted within thematic exhibitions. The Judgment of Paris, illustrating Homer’s Iliad, was displayed as part of Troy: Myth and Reality. A selection of Blake’s illustrations represented the tension between fact and fantasy in an exhibition accompanying the 2019 biennial conference of the British Association for Romantic Studies in Nottingham. In Extreme Nature!, Behemoth and Leviathan from Illustrations of the Book of Job came across as an attempt to imagine all-powerful biblical beasts, captured within the frame of a book illustration, as examples of restrained, domesticated, and vanquished pride. The National Maritime Museum used Blake’s miniature emblem captioned “I want! I want!,” featuring a tiny figure propping up a long ladder across the sky to bridge the distance between earth and moon, to introduce the imagining of moon travel among mythical and scientific specimens brought together to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the moon landing. Blake’s watercolor Christ Refusing the Banquet Offered by Satan from John Milton’s Paradise Regained exemplified the dynamic of temptation and abstinence in a religious relationship with food in Feast and Fast: The Art of Food in Europe, 1500–1800, while earlier series illustrating Paradise Lost and On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity were on view at Tate Britain as examples of the patronage of the Rev. Joseph Thomas. Versions of The Good and Evil Angels were on display in three exhibitions. The pen and watercolor from 1793–94 was central in shaping the demonic power and active energy of the elements in Fire: Flashes to Ashes in British Art, 1692–2019 from June to September, while in October it went home to The Higgins, where its child-snatching element was inflected in a new context in Dreams and Nightmares. Meanwhile, Tate Britain’s impression of the color print of 1795 appeared on the wall of an outdoor basketball court as part of the animation of a series of iconic works in Sam Gainsborough’s trailer for the Blake retrospective. Inside the gallery, it was hung among the twelve large color prints—whose only known contemporary collector was Thomas Butts—showing how they might work as a series translating the experience of Renaissance cycles within a bourgeois interior.