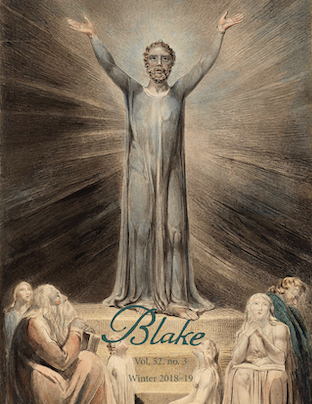

William Blake and the Age of Aquarius, Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University, September 2017–March 2018; Stephen F. Eisenman, ed., William Blake and the Age of Aquarius

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.47761/biq.231Abstract

“Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive, / But to be young was very heaven!” Thus Wordsworth looked back at the heady days of Paris in 1789 from the vantage point of 1805. Such nostalgia, of course, is a hallmark of Romanticism. Nor is it a simple recollection, but a multilayered process of memory: in this case, Wordsworth looks back at a time of looking forward, much as Blake writes in 1793 a “prophecy” of America in 1776. Then there is the memory of memory, as in Wordsworth’s “Tintern Abbey,” where the speaker remembers how a remembered scene has sustained him in the intervening five years. In the 1799 Prelude, he turns back to his earliest memories—“Was it for this?”—in an attempt to resolve his writer’s block. Looking backward in order to move forward is a quintessentially Romantic exercise, one complicated further by the uncertainty of imagining what “might will have been,” as Emily Rohrbach has shown (2).

Such was the case when I visited William Blake and the Age of Aquarius at the Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art at Northwestern University, curated by Stephen F. Eisenman. The exhibition explored how and why Blake became a role model for artistic revolutionaries in postwar America, building up to the countercultural upheaval of the 1960s. But this was not a straightforward study of one-way influence in which Blake served as background. In the catalogue, Lisa G. Corrin, director of the Block Museum, expresses “hope that seeing Blake against the backdrop of the ‘Age of Aquarius’ will enable us to reconnect to the radicalism of this iconic figure and to find in his multidimensional contributions meaning for our own tumultuous times” (vii). As Eisenman adds, “the products of both periods are potentially valuable resources for social movements still to come” (6). In a Romantic act of meta-recall, this exhibition recalls the recollection of Blake. Back in 1995, Morris Eaves referred to Blake’s perennial status as “the sign of something new about to happen” (414). That “something new” begins, as ever, with a Romantic glance backward.