| 1. William Blake, Industrious Cottager. Stipple and line engraving after George Morland, color printed. Platemark 27.3 x 30.5 cm. (all measurements are of platemarks unless otherwise specified), 1788. Collection of Robert N. Essick. |

| 1. William Blake, Industrious Cottager. Stipple and line engraving after George Morland, color printed. Platemark 27.3 x 30.5 cm. (all measurements are of platemarks unless otherwise specified), 1788. Collection of Robert N. Essick. |

| 1. William Blake, Industrious Cottager. Stipple and line engraving after George Morland, color printed. Platemark 27.3 x 30.5 cm. (all measurements are of platemarks unless otherwise specified), 1788. Collection of Robert N. Essick. |

|

|

| 2: BACKGROUND & CONTEXT |

|

Nevertheless, five of the six books listed in the prospectus as being “in illuminated printing” (E 693) were indeed printed in colored inks, usually yellow ochre, raw sienna, or green, but only in a single color in any one impression. Blake would print a few copies of each book in one printing session, often changing ink during the session for those books in print runs of more than ten copies (e.g., Songs of Innocence, The Book of Thel, and Visions of the Daughters of Albion) to diversify the copies, and had by this time printed approximately 62 copies of the six titles (Viscomi, Idea 376). Nearly all the pages making up these copies were finished in water colors. The coloring style was very simple, with just a few light washes in the images and rarely in the text areas. Blake adapted a standard practice for coloring prints, “washing” (i.e., painting in transparent water colors) sets of them with his assistant, his wife Catherine, before they were assembled as pages in books. The practice of coloring prints was a small cottage industry in England at this time (the colorist usually adding only one or two colors before passing the print to the next colorist, who adds her colors), and all the major printsellers, such as John and Josiah Boydell, Thomas Macklin, and James Sayers, offered separate prints both monochrome and colored. No one but Blake, however, offered works in “illuminated printing,” and no one but Blake was producing colored prints as illustrated text pages in books. By the fall of 1793, the illuminated books consisted of two kinds

of relief-etched prints, monochrome and colored. The popularity of color and colored prints—and the tonal intaglio

processes of stipple, aquatint, and mezzotint—reflects the period’s

interest in facsimile reproductions of paintings and drawings. Such

works conceal their “printness,” their graphic syntax by which an image

in one medium (oil painting, water color, etc.) is translated into another

medium (etching, mezzotint, etc.).

Given the coloring technique, it was impossible for any two such prints

to be identical, and because the “cheap drudges” employed by the printsellers

to “execute this delicate and difficult task” of finishing them in water

colors lacked the “practised hand, the cultivated eye, and the consummate

judgment of a master,” the resulting “performances must ever remain

unworthy [of] the attention of those who possess the smallest pretensions

to Taste.” Landseer’s criticism is harsh and biased, the view of the outsider

angry about the engraver’s lowly status as copyist—as well as about

losing his market share to tonal and color printmakers. Yet, he does

point to the inherent difficulty of color printing à la poupée.

Industrious Cottager, The alternative to printing multiple colors on one plate in a single pull through the press was to print multiple plates, all the same size, with each plate carrying one color and all the plates registered in exactly the same position on the paper. Landseer does not comment on multiple-plate color prints, probably because they were exceedingly rare. No one in England was using the technique in the 1790s, and only a few printers on the Continent were. But given that the technique was invented to produce prints that looked even more like their models than color prints produced in one pull through the press, he would have certainly disapproved. Nor would Landseer have been appeased by the separation of colors and the elimination of the need for the printer to be “an artist,” or even by impressions not having to be subjected to the hand-colorists, those “ignorant pretenders to Art . . . the cheap drudges . . . who can scarcely hold a pencil” (182). These, however, are the features that made multiple-plate printing more mechanical and thus more able to produce numerous and near-identical prints (Lilien 83). In other words, multiple plates were not only a way to ensure consistency, but also a way to eliminate the painter from the reproduction of paintings and drawings. The first color printing using multiple plates was “chiaroscuro” woodcuts in imitation of tinted drawings common in the Renaissance. Line drawings on tinted paper with highlights in white gouache (an opaque watercolor, sometimes called “body color”) were reproduced with a key or outline block and a second block cut in the broad shape of the wash with selected areas cut out so that the white of the paper would serve as the highlights (the so-called “German” type). To reproduce wash drawings in which the tints and highlights define both outline and modeling required reducing the drawing to three or four tints and cutting separate blocks for each, with highlights cut away from the blocks. The tone blocks overlapped to create intermediate tones (the “Italian” type). Chiaroscuro woodcuts were produced primarily in Italy and Germany in the 16th and 17th centuries, and eventually in France and the Netherlands. English engravers, however, did not learn the process until the early 18th century, and even then it was rarely practiced (Friedman 3). The few English engravers who produced chiaroscuro prints (e.g., Charles

Knapton, Elisha Kirkall, and Arthur Pond) used mezzotint or etched plates

as the key plate and wood blocks for tones and highlights, a mixed-method

technique that was first used by Nicolas Le Sueur in Paris for Crozat’s

Cabinet (1741), a collection of prints in imitation of old master

drawings. An earlier and even more intriguing venture in multiple-plate color

printing also failed. Jacques Christophe Le Blon (1667-1741), who was

trained as a painter and engraver, invented a way of “printing pictures”

(Le Blon 6) using three mezzotint plates, each printed in one of the

primary colors (red, yellow, blue, with occasionally a fourth plate

in black) and registered on the paper to reproduce all the compound

colors of the original drawing or painting. His first color prints were

produced c. 1704; in about 1720, he came to England where mezzotints,

which are ideally suited for reproducing the tonal gradations characteristic

of oil paintings, were far In the dedication to Coloritto (1725), Le Blon’s book on color theory, which explains the theory behind color printing but not the practice, he states that he “fell upon [his] Invention of Printing Objects in their natural Colours” while attempting to understand the theory of color, and that the invention assisted him in that understanding “till [he] arriv’d at the Skill of reducing the Harmony of Colouring in painting to Mechanical Practice, and under infallible Rules” (iv). Le Blon’s invention anticipates modern color separation, but he did not have the aid of cameras and optical filters to analyze the colors of a painting into the primary colors. This he did by eye and trial and error till he achieved the correct proportions of each color. He likened his theories about the mixture of “Material Colours” to Isaac Newton’s theories in the Optics on light, or “Impalpable Colours” (Le Blon iv). Although Le Blon’s three-color mezzotint process was not used in England after he returned to Paris, it was well known. Robert Dossie, in the Handmaid to the Arts (1758), described the technique and noted that it would remain “neglected . . . unless revived by the patronage of some great person or society, who may conveniently bear that expence, which artists . . . cannot prudently engage in” (2:185-86). The method was, however, continued in Paris by a few of Le Blon’s pupils. The best of them, Jacques Fabian Gautier D’Agoty, produced work that “shows a marked superiority to Le Blon’s,” particularly evident in his prints for Myologie complette of 1746 (Friedman 10). Printing multiple colors from one plate was the standard practice for producing color prints during Blake’s lifetime for good reason: it produced results closer to actual paintings than hand-colored black and white prints, and it cost less than any of the multiple-plate techniques. To summarize the two basic processes: in à la poupée printing, the plate is painted anew for each impression, which is then finished in water colors; in multiple-plate printing, each plate is inked in only one color, and the plates are registered to overlap in the impression to reproduce the secondary and tertiary colors and tones. The former requires a painter’s touch and mind; while the latter, dedicated to producing identical impressions, requires the eyes and hands of a printer skilled at registration. |

| 0:

SUGGESTIONS FOR READERS FOR OPTIMAL VIEWING 1: INTRODUCTION 2: BACKGROUND & CONTEXT 3: BLAKE'S COLOR PRINTING METHODS 4: THE TWO-PULL THEORY 5: THE ARGUMENTS FOR AND AGAINST TWO-PULL PRINTING 6: WHY "NURSES SONG" WAS PRINTED TWICE 7: OCCAM'S RAZOR 8: POSTSCRIPT: SOME IMPLICATIONS 9: NOTES 10: LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 11: WORKS CITED |

|

3. Elisha Kirkall, The Holy Family.

Mezzotint and chiaroscuro, 29.5 x 40.0 cm., 1724. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

|

|

| 4. John Baptist Jackson, Descent from the Cross, after Rembrandt. Chiaroscuro woodcut, 35.5 x 27.8 cm., 1738. Yale Center for British Art, University Art Gallery Collection, Gift of Ralph Kirkpatrick. |

|

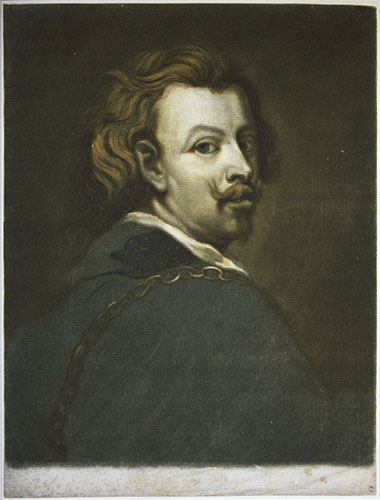

| 5. Jacques Christophe Le Blon, Van Dyck Self Portrait. Three-color mezzotint, 61.2 x 36.0 cm., c. 1720s. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. |

| 3. Elisha Kirkall, The Holy Family. Mezzotint and chiaroscuro, 29.5 x 40.0 cm., 1724. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. |

| 4. John Baptist Jackson, Descent from the Cross, after Rembrandt. Chiaroscuro woodcut, 35.5 x 27.8 cm., 1738. Yale Center for British Art, University Art Gallery Collection, Gift of Ralph Kirkpatrick. |

| 5. Jacques Christophe Le Blon, Van Dyck Self Portrait. Three-color mezzotint, 61.2 x 36.0 cm., c. 1720s. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. |

| 2. William Blake, Industrious Cottager. Stipple and line engraving after George Morland, color printed. Platemark 27.3 x 30.5 cm., 1788. Collection of Robert N. Essick. Detail showing the blending and overlapping of colors. |