|

e can

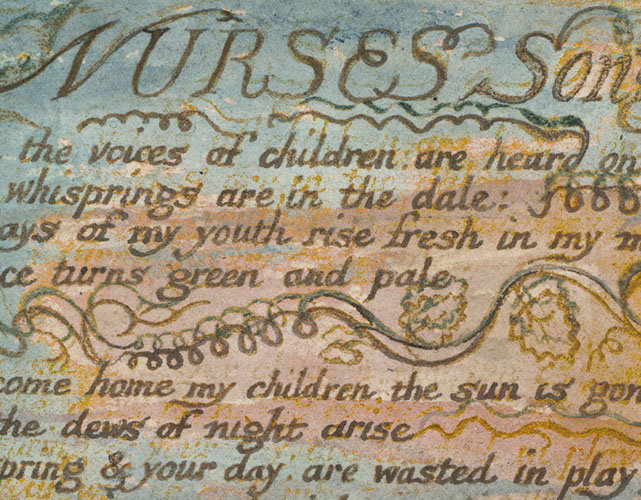

now return to the single most important piece of evidence cited by Phillips,

the “Nurses Song” (illus.

8) in the Experience section of Songs of Innocence and

of Experience copy E, where we are again confronted with the questions

of efficiency and waste. As we have seen, Blake was quite conscientious

about not wasting materials, foregoing bottom sheets, cutting his own

copper plates from larger sheets of copper, relief etching both sides

of most plates, using yellow ochre, green, and raw sienna pigments mostly

in the early years, which were the least expensive pigments in London

at the time (Viscomi, Idea 392-93n4), and trying to get more

than one impression from one inking. In fact, the lengths to which Blake

would go to avoid wasting materials can be seen in “Nurses Song” and

many of the other impressions in Songs of Innocence and of Experience

copy E. e can

now return to the single most important piece of evidence cited by Phillips,

the “Nurses Song” (illus.

8) in the Experience section of Songs of Innocence and

of Experience copy E, where we are again confronted with the questions

of efficiency and waste. As we have seen, Blake was quite conscientious

about not wasting materials, foregoing bottom sheets, cutting his own

copper plates from larger sheets of copper, relief etching both sides

of most plates, using yellow ochre, green, and raw sienna pigments mostly

in the early years, which were the least expensive pigments in London

at the time (Viscomi, Idea 392-93n4), and trying to get more

than one impression from one inking. In fact, the lengths to which Blake

would go to avoid wasting materials can be seen in “Nurses Song” and

many of the other impressions in Songs of Innocence and of Experience

copy E.

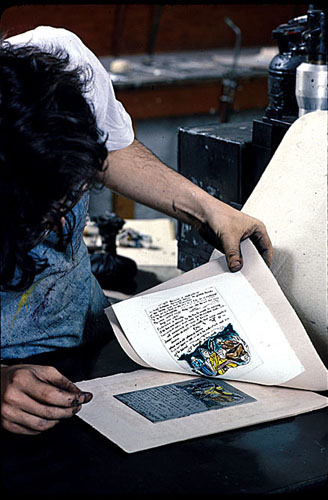

Copy E appears to have been compiled for Thomas Butts, Blake’s

chief patron for his water colors and tempera paintings, c. 1806. To

assemble the copy, Blake used impressions from various printing sessions:

1789, 1794, and c.1795 (see Viscomi, Idea 143, 145, 148-49).

Almost all of the impressions in copy E were printed in the same print

run as those forming  Songs

of Innocence and of Experience copies B, C, and D. A handful of

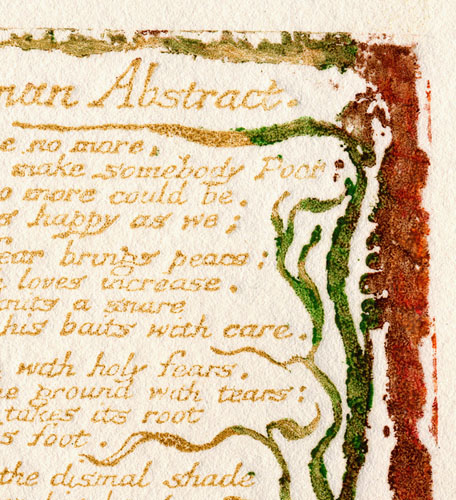

impressions in copy E were printed well, including “The Fly,”

“The Human Abstract,” and “Holy Thursday” (Experience),

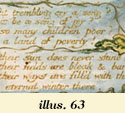

with texts dark and legible (illus. 63), but most appear to have been

so poorly printed that Blake did not use them in copies B, C, and D.

In spite of the poor quality of many of these unused impressions, Blake

did not discard them. In 1806, instead of setting up shop to print just

one copy for Butts, he gathered together these previously rejected Songs

of Innocence and of Experience copies B, C, and D. A handful of

impressions in copy E were printed well, including “The Fly,”

“The Human Abstract,” and “Holy Thursday” (Experience),

with texts dark and legible (illus. 63), but most appear to have been

so poorly printed that Blake did not use them in copies B, C, and D.

In spite of the poor quality of many of these unused impressions, Blake

did not discard them. In 1806, instead of setting up shop to print just

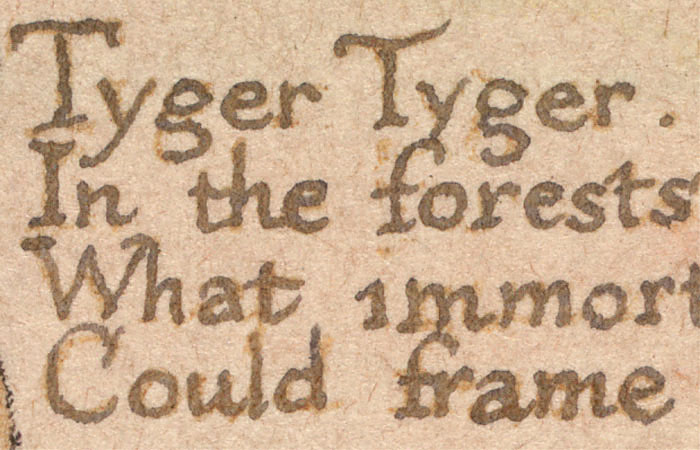

one copy for Butts, he gathered together these previously rejected impressions. Most of the texts, such as “The Tyger,” required

extensive rewriting with pen and ink because they were so lightly printed,

the result of being the second—or possibly even the third—pull

without re-inking (illus. 64). They are poor, in other words, precisely

because Blake tried to get too many impressions from one inking in a

thin, lightly colored ink. Indeed, if he had re-inked the plate each

time after the plate had been completely wiped of ink, as Phillips’

two-pull theory requires, then the impressions would not have been this

poor. They would all have been as dark as “Holy Thursday”

(Experience), which required no reworking (illus. 63). In effect,

Blake salvaged a set of mostly poorly printed impressions through considerable

handwork and recoloring and transformed it into one of his most intriguing

and technically complex copies of Songs of Innocence and of Experience.

impressions. Most of the texts, such as “The Tyger,” required

extensive rewriting with pen and ink because they were so lightly printed,

the result of being the second—or possibly even the third—pull

without re-inking (illus. 64). They are poor, in other words, precisely

because Blake tried to get too many impressions from one inking in a

thin, lightly colored ink. Indeed, if he had re-inked the plate each

time after the plate had been completely wiped of ink, as Phillips’

two-pull theory requires, then the impressions would not have been this

poor. They would all have been as dark as “Holy Thursday”

(Experience), which required no reworking (illus. 63). In effect,

Blake salvaged a set of mostly poorly printed impressions through considerable

handwork and recoloring and transformed it into one of his most intriguing

and technically complex copies of Songs of Innocence and of Experience.

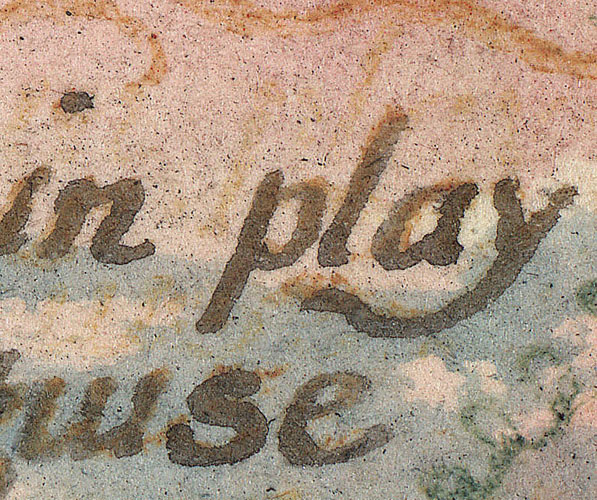

Though initially reluctant to include the poor impressions in the

copies of the Songs of Innocence and of Experience he compiled

and sold in the 1790s, Blake did not throw them out. He even kept “Nurses

Song,” despite the seriously flawed double printing. The very fact that

he kept “Nurses Song” strongly implies that he would have kept less

poorly registered impressions as well, which argues against the notion

that there are no other poorly registered color prints extant because

Blake’s technical standards were so high that he threw them away. Rather,

there are no poorly registered color prints other than “Nurses Song”

because only “Nurses Song” was printed twice, and, as we will see, only

in “Nurses Song” did Blake attempt a shortcut for repairing a poor impression:

reprinting the text rather than rewriting it by hand on the impression.

Phillips believes that Blake, for his color prints, printed in ink

for the first pull and in colors for the second pull through the press

(98-99). Thus, he concludes (or at least assumes) that “Nurses Song” was produced

in two printings, with the text in yellow ochre printed first,

Thus, he concludes (or at least assumes) that “Nurses Song” was produced

in two printings, with the text in yellow ochre printed first,  and

the tendrils in green pigment second. This is, indeed, how it looks

to the naked eye. The darker, denser color appears to lie on top of

the lighter, thinner yellow ochre wherever one color crosses over the

other. But this is an illusion. and

the tendrils in green pigment second. This is, indeed, how it looks

to the naked eye. The darker, denser color appears to lie on top of

the lighter, thinner yellow ochre wherever one color crosses over the

other. But this is an illusion.  With

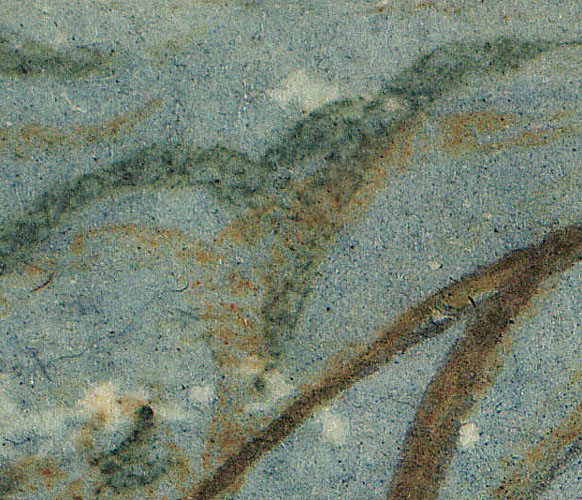

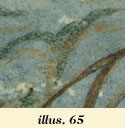

a magnifying glass, one can see flecks of the yellow ochre ink lying

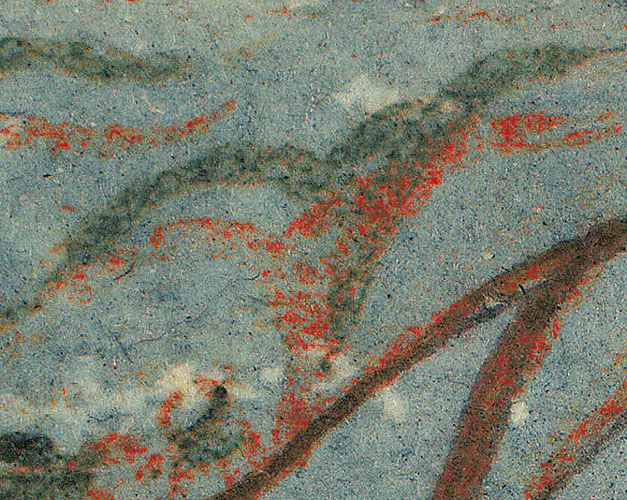

on top of the green pigment (illus. 65). By changing the yellow to red

on a computer, this effect of the lighter color lying on top of the

darker color is more easily seen (illus. 66). The illusion itself is

easy to replicate. In illustration 67, showing a plate printed by the

authors, the green appears on top of the yellow, but the green was actually

printed first and the yellow over it. With

a magnifying glass, one can see flecks of the yellow ochre ink lying

on top of the green pigment (illus. 65). By changing the yellow to red

on a computer, this effect of the lighter color lying on top of the

darker color is more easily seen (illus. 66). The illusion itself is

easy to replicate. In illustration 67, showing a plate printed by the

authors, the green appears on top of the yellow, but the green was actually

printed first and the yellow over it.

Yellow ink on top of green color means that the inked text was printed

after the color printing in green—the reverse of the sequence

that Phillips proposes for all two-pull color printing. On even closer

examination, one can see why Blake printed the text after he had printed

the colors. He was actually reprinting the text. He had printed

the plate à la poupée, with ink and colors together, in the style

of the other color-printed plates in Songs of Innocence and of Experience

copy E. The colors printed well but the text was exceptionally faint

and illegible, the  result

of his not re-inking the plate after the previous impression and trying

to get one too many impressions from one inking. result

of his not re-inking the plate after the previous impression and trying

to get one too many impressions from one inking. But the text was there on the paper, and traces of it

But the text was there on the paper, and traces of it  can

be seen under magnification (illus. 68). This first text becomes very

apparent when the traces of yellow ochre pigments are overly saturated

electronically using Adobe Photoshop software (illus. 69). What was

hardly noticeable to the naked eye becomes easily can

be seen under magnification (illus. 68). This first text becomes very

apparent when the traces of yellow ochre pigments are overly saturated

electronically using Adobe Photoshop software (illus. 69). What was

hardly noticeable to the naked eye becomes easily visible by magnification and computer enhancement (illus. 70). Because

the color-printed illustration looked acceptable but the text was almost

invisible, Blake attempted to re-ink the text and print or stamp it

into place, thereby saving himself from having to trace over the faint

or illegible letters in pen and ink. But the registration was poor;

the newly printed text is displaced below its first, exceedingly weak,

printing. The experiment had failed; the second printing was also too

lightly printed and Blake was forced to go over the second printing

of the text in pen and ink. He did not try the two-pull technique on

any of the other plates in Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy

E or probably ever again. At the very least, there is no extant evidence

that he tried this flawed technique of two-pull printing beyond this

single example. Many of the texts in books subsequently printed, such

as Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy AA and its sister

copy, the often-reproduced copy Z, were very light and in need

of repair (illus.

60). Blake did not try to reprint the texts but wrote over them

in pen and ink on the paper.

visible by magnification and computer enhancement (illus. 70). Because

the color-printed illustration looked acceptable but the text was almost

invisible, Blake attempted to re-ink the text and print or stamp it

into place, thereby saving himself from having to trace over the faint

or illegible letters in pen and ink. But the registration was poor;

the newly printed text is displaced below its first, exceedingly weak,

printing. The experiment had failed; the second printing was also too

lightly printed and Blake was forced to go over the second printing

of the text in pen and ink. He did not try the two-pull technique on

any of the other plates in Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy

E or probably ever again. At the very least, there is no extant evidence

that he tried this flawed technique of two-pull printing beyond this

single example. Many of the texts in books subsequently printed, such

as Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy AA and its sister

copy, the often-reproduced copy Z, were very light and in need

of repair (illus.

60). Blake did not try to reprint the texts but wrote over them

in pen and ink on the paper.

A close examination of “Nurses Song” and the other impressions in Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy E reveals

that Blake inked the text area of the plates locally,

impressions in Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy E reveals

that Blake inked the text area of the plates locally,  presumably

with small inking dabbers, adding at least a few colors with each pull,

but adding ink only every other or third pull, which accounts for the

inconsistent saturation of ink and the consistently solid color pigments

among the impressions. These procedures and their results are easy presumably

with small inking dabbers, adding at least a few colors with each pull,

but adding ink only every other or third pull, which accounts for the

inconsistent saturation of ink and the consistently solid color pigments

among the impressions. These procedures and their results are easy  to

replicate. Illustration 71 is a facsimile plate color printed à la

poupée in yellow ochre ink and in green, brown, and red pigments.

The text was inked locally with a small roller and the colors applied

with stump brushes. The plate was printed without re-inking and recoloring

to produce illustration 72, which is noticeably lighter in ink and colors

but acceptable. Illustration 73 is a third impression from the same

plate with colors added but without re-inking. The illustration is strong

but the text is too light to be legible. This is the condition “Nurses

Song” was in before Blake tried to fix it by stamping a re-inked text

into place. to

replicate. Illustration 71 is a facsimile plate color printed à la

poupée in yellow ochre ink and in green, brown, and red pigments.

The text was inked locally with a small roller and the colors applied

with stump brushes. The plate was printed without re-inking and recoloring

to produce illustration 72, which is noticeably lighter in ink and colors

but acceptable. Illustration 73 is a third impression from the same

plate with colors added but without re-inking. The illustration is strong

but the text is too light to be legible. This is the condition “Nurses

Song” was in before Blake tried to fix it by stamping a re-inked text

into place.

Blake printed in the à la poupée manner, literally painting

on his plates. Indeed, printing relief etchings à la poupée was

easier than printing intaglio plates in the same technique because the

ink

and colors did not have to be wiped off the surface of the plates. Nevertheless,

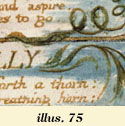

the ink and colors do blend where they meet, as can be seen in the detail

of The Song of Los copy E plate 6 (illus. 74) and “The Lilly”

from Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy E ink

and colors did not have to be wiped off the surface of the plates. Nevertheless,

the ink and colors do blend where they meet, as can be seen in the detail

of The Song of Los copy E plate 6 (illus. 74) and “The Lilly”

from Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy E  (illus.

75). They are “unavoidably . . . blurred and confounded” (Landseer 182)—albeit

skillfully and to good effect—as in all à la poupée prints (illus.

2, 75). If Blake had printed the plates twice, one would expect

to see both overlapping of colors onto ink and gaps between colors and

ink, rather then the subtle mixing of the two, because with the ink

wiped from the plate, Blake would not have known exactly where to apply

the colors. There is no clear division on a plate between text and illustration;

tendrils, for example, run through both areas. Applying colors on a

clean plate, in other words, would have been guesswork, even if the

impression (pinned by the roller back at the press?) was consulted. (illus.

75). They are “unavoidably . . . blurred and confounded” (Landseer 182)—albeit

skillfully and to good effect—as in all à la poupée prints (illus.

2, 75). If Blake had printed the plates twice, one would expect

to see both overlapping of colors onto ink and gaps between colors and

ink, rather then the subtle mixing of the two, because with the ink

wiped from the plate, Blake would not have known exactly where to apply

the colors. There is no clear division on a plate between text and illustration;

tendrils, for example, run through both areas. Applying colors on a

clean plate, in other words, would have been guesswork, even if the

impression (pinned by the roller back at the press?) was consulted.

As Landseer recognized, these “blurred and confounded” colors, the

“incidental smearings and errors of the printer in colours,” can “be

rectified by the author of the original picture . . . or some person

of equal, and of similar powers, and capable of entering into his views”

(182-83). Blake certainly was that rare individual, a printer who was also a painter, who thought in terms

of the whole process—from blotting and blurring to organizing the “chaotic

confusion” (Landseer 182) with firm bounding lines. He had to, since

color printing, especially from both levels of the plate, could obliterate

form, as is demonstrated by the unfinished impressions of The Book

of Urizen plates 1 and 5 in the Yale Center for British Art, the

sequentially printed proofs of plate 25 in the Fitzwilliam Museum and

Beinecke Library (illus. 29,

30), and the

facsimile of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell plate 10 (illus.

76). It was a two-step process not unlike J. M. W. Turner’s on

Varnishing Day in the Royal Academy, when he would transform a roughly

painted canvas into a finished work of art in a few hours, or Alexander

Cozen’s “New Method,” in which the initial form was indeterminate

blots and blurs subsequently given meaning through line. Blake must

have been thinking in terms of the whole process—printing the entire

image in ink and colors and finishing in water colors and pen and ink.

Why would he try to divide and sanitize the process by printing the

two parts separately?

individual, a printer who was also a painter, who thought in terms

of the whole process—from blotting and blurring to organizing the “chaotic

confusion” (Landseer 182) with firm bounding lines. He had to, since

color printing, especially from both levels of the plate, could obliterate

form, as is demonstrated by the unfinished impressions of The Book

of Urizen plates 1 and 5 in the Yale Center for British Art, the

sequentially printed proofs of plate 25 in the Fitzwilliam Museum and

Beinecke Library (illus. 29,

30), and the

facsimile of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell plate 10 (illus.

76). It was a two-step process not unlike J. M. W. Turner’s on

Varnishing Day in the Royal Academy, when he would transform a roughly

painted canvas into a finished work of art in a few hours, or Alexander

Cozen’s “New Method,” in which the initial form was indeterminate

blots and blurs subsequently given meaning through line. Blake must

have been thinking in terms of the whole process—printing the entire

image in ink and colors and finishing in water colors and pen and ink.

Why would he try to divide and sanitize the process by printing the

two parts separately?

Blake did not fear chaos, inconsistency, or the absence of identical

impressions, and he had no need to mechanize his production. Mechanization

(e.g., an image divided into parts, uniform plates with pinholes for

registering paper, or marked up bottom sheets for plates) makes sense

when producing wallpaper (J. B. Jackson) or large print runs (Le Blon

believed he could produce 3000 impressions [Lilien 122]), or when fidelity

to the model and uniformity among impressions were the objectives. But

it does not make sense for small runs like Blake’s or for a painter-printmaker

free of models and given to improvisation. And for Blake to mechanize

his process—or even think in those terms—he would have had to begin

with copperplates that were uniform in size. That Blake thought in terms

of color printing even at the etching stage is indicated by the plates

of The Book of Urizen, which were etched less deeply than those

in Songs of Innocence and of Experience, The Marriage of Heaven

and Hell, and The Book of Thel, apparently to facilitate

printing colors from the shallows. In 1794, with his so-called “Urizen”

books, Blake had the opportunity to cut identically sized plates. He

did not take it. He used the versos of the Marriage plates for

Urizen, and in the following year for The Song of Los,

The Book of Los, and The Book of Ahania used a variety

of plate sizes.

|