|

t has

long been thought, by the present authors among others, that Blake painted

his plates using the standard à la poupée technique, adapted

for his purposes. Compared to any alternatives, the method is direct,

cost effective, and united with the art of painting (Essick, Printmaker

125-35; Friedman 16; Viscomi, Idea 119-28). Phillips does not

believe this, but, citing Le Blon and Jackson as precedents, argues

that Blake adapted the more complicated manner of printing and registering

multiple plates by printing his own plates twice, once for the text

in ink and again for the illustration in colors (95). It may seem that

questions about printing technique in general and color printing in

particular are of no real importance, but, as we argue below, using

one or the other method significantly affects our ideas about Blake’s

works and their conceptual implications. Phillips recognizes what is

at stake, for he claims that by not recognizing the two-pull method

we are grossly underestimating the “time and skill” Blake invested in

color printing and misunderstanding his “intentions as a graphic artist”

and his intended audience (95). On these issues Phillips says little

beyond some general observations on Blake’s intended audience in his

“Conclusion” (111-13). Nor does he develop further the effect of his

theory on our understanding of Blake as artist, printmaker, theorist

or poet. Surprisingly, Phillips does not argue (let alone prove) that

Blake’s visual effects in color printing were not possible with

single-pull printing. In short, he does not directly consider (much

less answer) the crucial question: Why divide the printing process into

text (first pull) and illustration (second pull) to reunite them on

paper if it was technically and aesthetically unnecessary to do so? t has

long been thought, by the present authors among others, that Blake painted

his plates using the standard à la poupée technique, adapted

for his purposes. Compared to any alternatives, the method is direct,

cost effective, and united with the art of painting (Essick, Printmaker

125-35; Friedman 16; Viscomi, Idea 119-28). Phillips does not

believe this, but, citing Le Blon and Jackson as precedents, argues

that Blake adapted the more complicated manner of printing and registering

multiple plates by printing his own plates twice, once for the text

in ink and again for the illustration in colors (95). It may seem that

questions about printing technique in general and color printing in

particular are of no real importance, but, as we argue below, using

one or the other method significantly affects our ideas about Blake’s

works and their conceptual implications. Phillips recognizes what is

at stake, for he claims that by not recognizing the two-pull method

we are grossly underestimating the “time and skill” Blake invested in

color printing and misunderstanding his “intentions as a graphic artist”

and his intended audience (95). On these issues Phillips says little

beyond some general observations on Blake’s intended audience in his

“Conclusion” (111-13). Nor does he develop further the effect of his

theory on our understanding of Blake as artist, printmaker, theorist

or poet. Surprisingly, Phillips does not argue (let alone prove) that

Blake’s visual effects in color printing were not possible with

single-pull printing. In short, he does not directly consider (much

less answer) the crucial question: Why divide the printing process into

text (first pull) and illustration (second pull) to reunite them on

paper if it was technically and aesthetically unnecessary to do so?

According to Phillips, Blake produced his color prints by inking the

plate’s text areas, registering the paper to plate, printing and removing

the paper, wiping the ink off the plate, adding colors, registering

the paper exactly to the colored plate, printing and removing the twice-printed

paper from the bed of the rolling press, and (presumably after drying)

finishing it in water colors (95, 101, 107). To produce another print

from the same copperplate, Blake would then begin the process anew by

wiping the plate of its colors, inking the text areas, registering,

printing, wiping the ink, adding colors, registering, and finally printing.

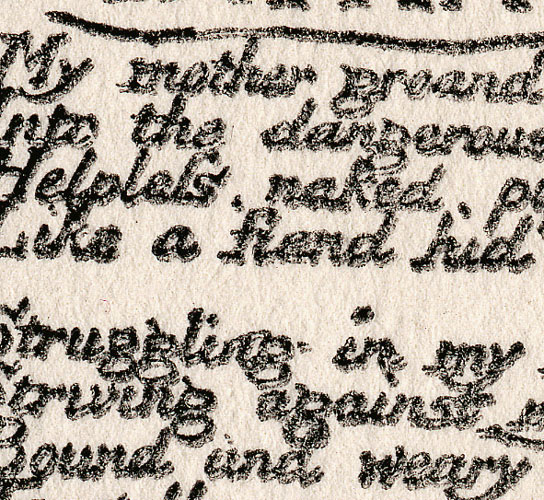

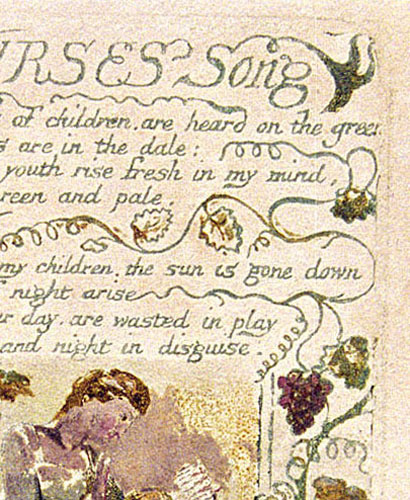

Phillips claims that a significant part of his evidence for this labor-intensive

method in which text is printed first and illustration second lies in

the “Nurses Song” from Songs of Experience in Songs of Innocence

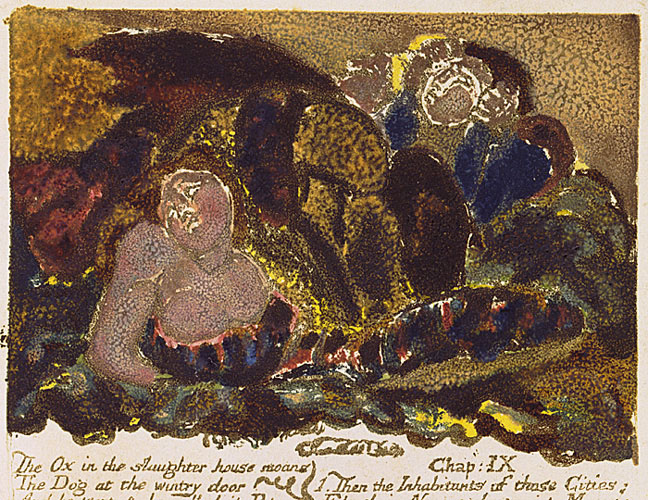

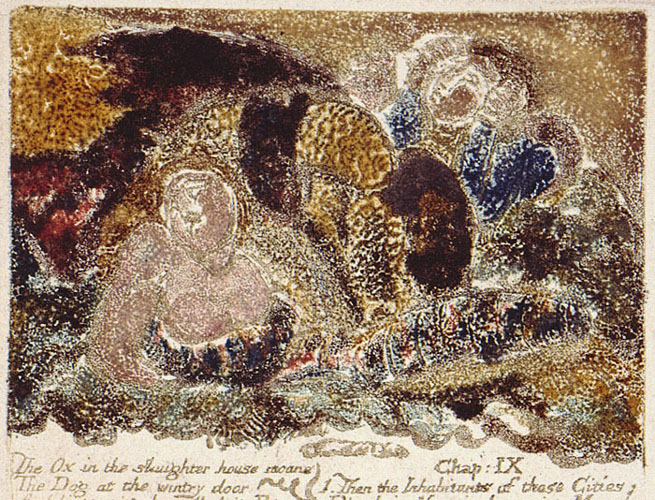

and of Experience copy E (illus. 8). One can plainly see that this impression was indeed printed

twice, as Essick and Viscomi separately recognized, but which they,

according to Phillips, incorrectly identified as an individual aberration

rather than as one of the most significant clues in revealing Blake’s

color printing practice (Essick, Printmaker 127; Phillips 103;

Viscomi, Idea 119). Phillips implies that this “Nurses Song”

deviates from other color prints only in that, unlike them, it is misregistered,

whereas all the other extant color prints were perfectly registered.

(illus. 8). One can plainly see that this impression was indeed printed

twice, as Essick and Viscomi separately recognized, but which they,

according to Phillips, incorrectly identified as an individual aberration

rather than as one of the most significant clues in revealing Blake’s

color printing practice (Essick, Printmaker 127; Phillips 103;

Viscomi, Idea 119). Phillips implies that this “Nurses Song”

deviates from other color prints only in that, unlike them, it is misregistered,

whereas all the other extant color prints were perfectly registered.

Phillips cites Le Blon as an example of multiple-plate printing to

make the point that registering a plate onto a prior impression was

possible (95-96). He states that for the three primary colors to be

recombined into the original colors meant that “the precision of the

registration had to be absolute” (96). From this statement, one might

infer that Le Blon’s color prints show no signs of the second or third

plate—that is, reveal no signs of their mode of production—but that

one plate was registered on top of an impression from the other so precisely

that all telltale tracks were covered. That, however, never happens.

Color prints produced with two or more plates or blocks—despite

the plates being exactly the same size—always show signs of their

production, usually to the naked eye but always

under magnification or computer enhancement. We have yet

to find a multi-plate (and hence multi-printed) color print that

does not show evidence of at least slight misregistration at

some point along its margins, usually at or near the corners. Such evidence

generally appears in two forms: either as multiple platemarks and/or

as a displacement of one color just outside another. For example, the

top right corner of Le Blon’s Van Dyck Self Portrait (illus.

9) reveals one plate extending past the other. This effect is even clearer

in the bottom right corner of Le Blon’s Narcissus (c. 1720s)

(illus. 10).

We see the same effect in all twenty of the prints in D’Agoty’s Myologie,

including plate 3 (illus. 11), which were thought by contemporaries

to be superior to Le Blon’s, and in all 53 of his smaller three-color

mezzotints for Observations sur l’histoire naturelle, sur la

physique et sur la peinture (1752-55), such as the Tortuise

(illus. 12). Even the excellent two-color stipples of Louis Bonnet, such

as Head of a Young Girl Turned toward the Left (1774) (illus. 13),

reveal in their corners two platemarks, one slightly displaced

from the other (illus. 14).

The signs of production are also visible in the very best impressions of

the mixed-method and pure chiaroscuro prints, including Kirkall’s Holy

Family and Jackson’s Descent from the Cross, where  the

tonal blocks extend slightly past the key blocks (illus. 15-16). Even

Jackson’s Venetian series—thought to be “without doubt the high point

of chiaroscuro printing” (Friedman 6)—reveal their mode of production,

as the corner of Holy Family and Four Saints, after Veronese (1739),

demonstrates (illus. 17). In all of these illustrations, it is fairly

easy to see the misregistrations. the

tonal blocks extend slightly past the key blocks (illus. 15-16). Even

Jackson’s Venetian series—thought to be “without doubt the high point

of chiaroscuro printing” (Friedman 6)—reveal their mode of production,

as the corner of Holy Family and Four Saints, after Veronese (1739),

demonstrates (illus. 17). In all of these illustrations, it is fairly

easy to see the misregistrations.

Such subtle misregistrations are not signs of poor printing. They

are to be expected, as printing manuals today acknowledge, regardless

of the registration mechanism used, because damp printing paper stretches

and shrinks in the course of printing the first and subsequent plates

(Hayter 58, Romano and Ross 121, Dawson 100). Reviewing the various

techniques used in his Atelier 17 for registering and printing multiple

plates, Hayter, one of the greatest technicians of twentieth-century

printmaking, states that “it is worthy of note that none of these methods

is absolutely precise” and “examination of the edges of colour prints

made by this system [i.e., multiple plates] will nearly always show

some errors of registration between the different colours . . . ” (58).

Slight misalignments, however, will not disrupt the visual logic and

impact of the design; our eyes tend to make adjustments or “read” a

slight fuzziness in an image as a pleasingly painterly style. The visual

effect of multiple-plate color prints, in other words, was not dependent

on absolute precision but on colors being overlaid one on top of the

other. But the same eyes cannot be fooled when focused on the margins.

“Absolute” (Phillips 96) accuracy in registration was impossible.

“Nurses Song” in the Experience section of the combined Songs

of Innocence and of Experience copy E (illus.

8) clearly reveals its double printing. The next place to look for

evidence of Blake printing his plates twice—on the grounds that modes

of production can never completely conceal themselves, at least not

to magnification and computers—is his other color prints, more than

650 of them. Given how poorly printed “Nurses Song” is, one would reasonably

expect to find other examples of misalignment, albeit less overt. Yet

not one of Blake’s other color prints reveals any sign of misregistration

of the plate onto the impression previously printed in ink. Any suggestion

that none exists because poorly printed impressions were thrown away

ought to give one pause. Such a practice is refuted by “Nurses Song”

and many of the other poorly printed impressions in Songs of Innocence

and of Experience copy E and other illuminated books. It seems clear

that Blake rarely threw away anything he printed that might be salvageable.

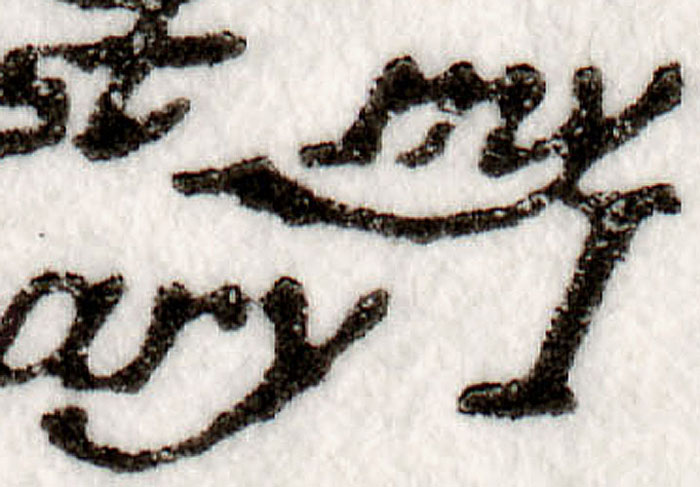

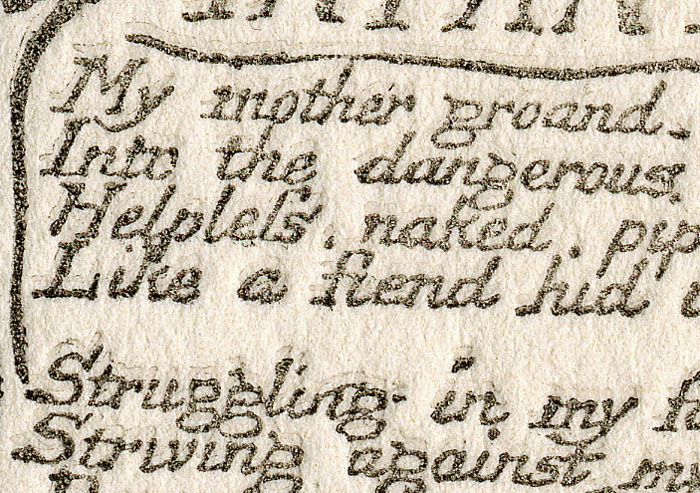

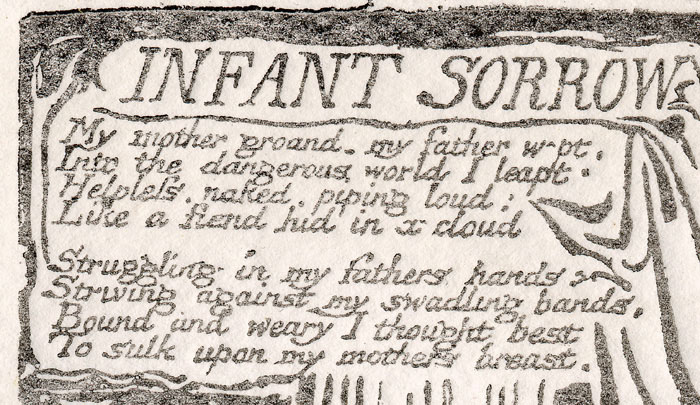

He had little concern with the finer points of precision printing.  If “Nurses Song” was acceptable (as its inclusion in a complete

copy of the

If “Nurses Song” was acceptable (as its inclusion in a complete

copy of the  Songs

of Innocence and of Experience sold to his major patron indicates),

then any print less obviously misaligned would be too, including hairline

misalignments not easily seen with the naked eye but visible under magnification.

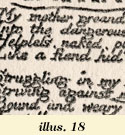

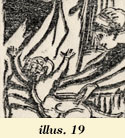

One would expect to see quite a few impressions looking like illustrations

18 and 19, where the text and designs, having been printed twice, are

slightly out of register. It takes only a hairline misalignment

of the second plate on top of an impression from the first—or Songs

of Innocence and of Experience sold to his major patron indicates),

then any print less obviously misaligned would be too, including hairline

misalignments not easily seen with the naked eye but visible under magnification.

One would expect to see quite a few impressions looking like illustrations

18 and 19, where the text and designs, having been printed twice, are

slightly out of register. It takes only a hairline misalignment

of the second plate on top of an impression from the first—or  on

top on

top  of

a prior impression from the same plate—to produce this out-of-focus

effect. This is especially true with relief etchings like Blake’s, because

the images are essentially in outline rather than tonal areas, which

makes printing them twice analogous to double printing the key block

in a chiaroscuro woodcut or mixed-method chiaroscuro. Even impressions

that appear dead on, such as illustration 20, reveal, when of

a prior impression from the same plate—to produce this out-of-focus

effect. This is especially true with relief etchings like Blake’s, because

the images are essentially in outline rather than tonal areas, which

makes printing them twice analogous to double printing the key block

in a chiaroscuro woodcut or mixed-method chiaroscuro. Even impressions

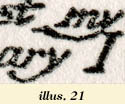

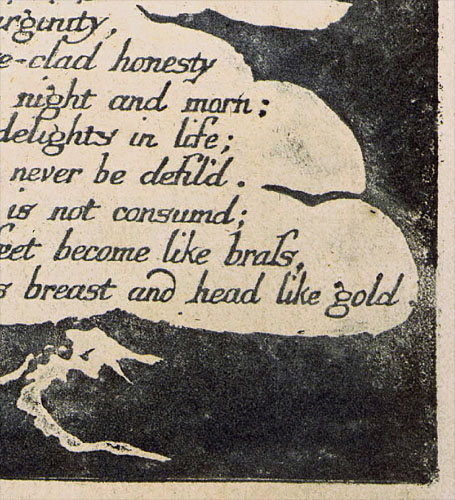

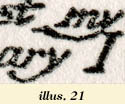

that appear dead on, such as illustration 20, reveal, when  magnified,

the soft edges along the letters that evince a second printing (illus.

21). In impressions printed magnified,

the soft edges along the letters that evince a second printing (illus.

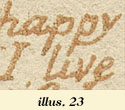

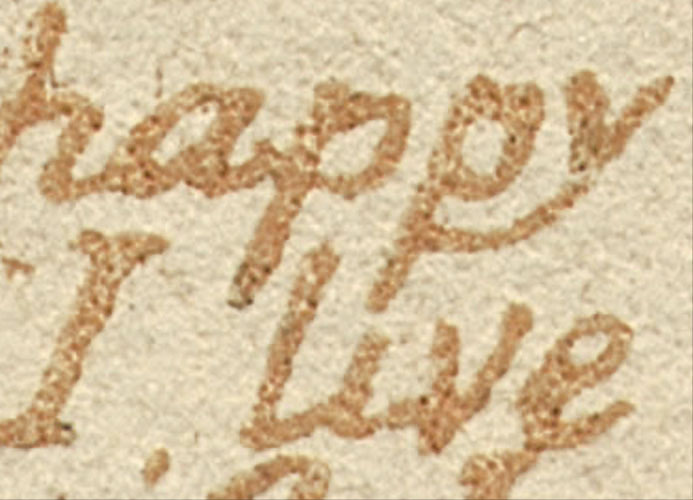

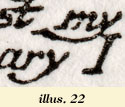

21). In impressions printed  once,

letters and other relief lines do not have any such ghosting (illus.

22), an absence characteristic of Blake’s color prints, as is demonstrated

by details of “The Fly” and “Holy Thursday” (Experience) from

Songs of Innocence and of Experience copies G and E (illus. 23,

63)

respectively. once,

letters and other relief lines do not have any such ghosting (illus.

22), an absence characteristic of Blake’s color prints, as is demonstrated

by details of “The Fly” and “Holy Thursday” (Experience) from

Songs of Innocence and of Experience copies G and E (illus. 23,

63)

respectively.

Phillips is correct to assume that Blake would have had to wipe the

plate completely clean of ink before adding colors (95, 101), and then

wipe the color off the plate before adding ink to pull a second impression.

This is necessary to help disguise even the slightest errors in registration,

for, as we have seen, if even minute traces of ink remain on the plate

during its second printing and the registration is anything less than

absolutely exact, then it will produce a slightly fuzzy impression.

The same is true for the colors: if they are left on the plate, then

they will be printed twice in the subsequent impression, once with the

ink and once when colors are replenished. The slightest misregistration

will show up. Masking techniques  like

these, however, work only to a point; the subtlest of misalignment may

fall below the threshold of vision, but it can be detected with magnification

and computer enhancement because relief lines or areas, even when devoid

of ink or colors, still slightly emboss the paper around their edges.

For example, the plate borders in “Nurses Song” in Songs of Innocence

and of Experience copy F were wiped of ink but still embossed the

paper (illus. 24). Such embossment is especially noticeable even without

magnification in impressions color printed from both the relief plateaus

and etched valleys of plates, such like

these, however, work only to a point; the subtlest of misalignment may

fall below the threshold of vision, but it can be detected with magnification

and computer enhancement because relief lines or areas, even when devoid

of ink or colors, still slightly emboss the paper around their edges.

For example, the plate borders in “Nurses Song” in Songs of Innocence

and of Experience copy F were wiped of ink but still embossed the

paper (illus. 24). Such embossment is especially noticeable even without

magnification in impressions color printed from both the relief plateaus

and etched valleys of plates, such  as

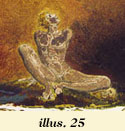

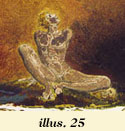

those in Songs of Innocence and of Experience copies F, G, H,

and T1, The Book of Urizen as

those in Songs of Innocence and of Experience copies F, G, H,

and T1, The Book of Urizen

copies

A, C, D, E, F, and J, Visions of the Daughters of Albion copy

F, and The Marriage of Heaven and Hell copy F, as is clearly

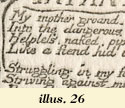

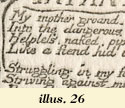

evident in its plate 21 (illus. 25). If Blake printed his plates twice

with pressure sufficient to print colors from the shallows, then the

second printing, despite its carrying no ink, will reveal itself as

a set of embossed lines around the printed lines (illus. 26). No embossments

or haloes of this kind are found in Blake’s color prints. copies

A, C, D, E, F, and J, Visions of the Daughters of Albion copy

F, and The Marriage of Heaven and Hell copy F, as is clearly

evident in its plate 21 (illus. 25). If Blake printed his plates twice

with pressure sufficient to print colors from the shallows, then the

second printing, despite its carrying no ink, will reveal itself as

a set of embossed lines around the printed lines (illus. 26). No embossments

or haloes of this kind are found in Blake’s color prints.

Even wiping the plate of ink and colors between pulls cannot erase

the signs of a second printing. Moreover, wiping oily ink  usually

leaves signs, as is evinced by usually

leaves signs, as is evinced by  the

traces of ink on and along plate borders that Blake wiped of ink (illus.

27a-27b). There are hundreds of examples of such traces because Blake

wiped the borders of nearly all illuminated prints produced by 1794

(see, for example, illus. 51,

53). In addition,

wiping ink and colors for every pull is extremely wasteful in practice.

Inking and printing pressure normal for relief can yield up to five

useable prints from one inking in a dark color. Illustration 28 the

traces of ink on and along plate borders that Blake wiped of ink (illus.

27a-27b). There are hundreds of examples of such traces because Blake

wiped the borders of nearly all illuminated prints produced by 1794

(see, for example, illus. 51,

53). In addition,

wiping ink and colors for every pull is extremely wasteful in practice.

Inking and printing pressure normal for relief can yield up to five

useable prints from one inking in a dark color. Illustration 28 ,

for example, is the third impression printed from one inking of a facsimile

plate. Indeed, in the Tate Britain exhibition, the second pulls printed

from facsimile plates were all more Blake-like than the first pulls,

which were too dark. With lighter inks, like the yellow ochre used in

Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy E, one can produce

at least two acceptable impressions (illus.

71, 72,

73). The pigments,

oil, and glues used to make inks and colors cost money, and so do rags

used to wipe the plates clean. These unnecessary expenses and the time

required to clean oily ink and glue-based colors from the copperplates

between each impression make this method of color printing expensive

and labor-intensive for no aesthetic gain, for it creates prints without

any visual differences (other than the telltale signs of double printing)

from those produced with single pulls at far less effort and cost. ,

for example, is the third impression printed from one inking of a facsimile

plate. Indeed, in the Tate Britain exhibition, the second pulls printed

from facsimile plates were all more Blake-like than the first pulls,

which were too dark. With lighter inks, like the yellow ochre used in

Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy E, one can produce

at least two acceptable impressions (illus.

71, 72,

73). The pigments,

oil, and glues used to make inks and colors cost money, and so do rags

used to wipe the plates clean. These unnecessary expenses and the time

required to clean oily ink and glue-based colors from the copperplates

between each impression make this method of color printing expensive

and labor-intensive for no aesthetic gain, for it creates prints without

any visual differences (other than the telltale signs of double printing)

from those produced with single pulls at far less effort and cost.

But one need not argue the point hypothetically about labor, time,

money, and materials, or even about the astonishing absence of fuzzy

impressions, ghost texts, and embossed haloes unavoidable in two-pull

printing. To this negative evidence that argues against the two-pull

hypothesis we can add a wealth of positive evidence that  Blake

did not wipe his plates of ink or color between pulls but continued

to replenish the ink and colors. Printmakers are led by the physical

properties of their materials to replenish ink instead of wiping and

starting over again Blake

did not wipe his plates of ink or color between pulls but continued

to replenish the ink and colors. Printmakers are led by the physical

properties of their materials to replenish ink instead of wiping and

starting over again  because

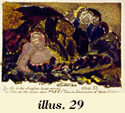

ink transfers best once the plate is worked up. The repetition of inking

accidentals and colors in sequentially pulled prints, such as the two

proof impressions of The Book of Urizen plate 25, color printed

but not finished in watercolors because

ink transfers best once the plate is worked up. The repetition of inking

accidentals and colors in sequentially pulled prints, such as the two

proof impressions of The Book of Urizen plate 25, color printed

but not finished in watercolors  (illus.

29-30), or the finished impressions of plate 24 in copies F and C (illus.

31-32), demonstrates that Blake printed more than one impression from

an inked plate and added ink and colors to a pre-existing base. (illus.

29-30), or the finished impressions of plate 24 in copies F and C (illus.

31-32), demonstrates that Blake printed more than one impression from

an inked plate and added ink and colors to a pre-existing base.

To

assume otherwise is to assume that repetition of colors and their placement

was due to Blake trying to replicate the previous impression—i.e., reproducing

a model—but, given the differences introduced, doing a very poor job

of it. Clearly, it is more reasonable to conclude that the repetition

of accidentals is due to Blake not wiping the plate clean between

impressions than to conclude that he minutely copied irrelevant and

even visually disruptive droplets and smudges of ink or color, using

the prior impression as his model. The To

assume otherwise is to assume that repetition of colors and their placement

was due to Blake trying to replicate the previous impression—i.e., reproducing

a model—but, given the differences introduced, doing a very poor job

of it. Clearly, it is more reasonable to conclude that the repetition

of accidentals is due to Blake not wiping the plate clean between

impressions than to conclude that he minutely copied irrelevant and

even visually disruptive droplets and smudges of ink or color, using

the prior impression as his model. The  repetition

of colors, and in some cases their diminishing intensity because Blake

did not add more color for a second impression, lead to the same conclusion.

Even the impression of “Nurses Song” that was printed twice,

the very grounds for the two-pull hypothesis and for thinking that text

and illustration were printed separately, shows two top plate borders

in yellow ochre ink (illus. 33), which means that ink was printed with

the colors and not wiped between pulls. repetition

of colors, and in some cases their diminishing intensity because Blake

did not add more color for a second impression, lead to the same conclusion.

Even the impression of “Nurses Song” that was printed twice,

the very grounds for the two-pull hypothesis and for thinking that text

and illustration were printed separately, shows two top plate borders

in yellow ochre ink (illus. 33), which means that ink was printed with

the colors and not wiped between pulls.

While one would expect to see fuzzy impressions and other signs of

misregistration in two-pull printing, what one would not expect to see

are perfectly clean fine white lines bordering the relief areas of prints

color printed from both levels. For example, in illustrations 25,

29, 30,

31, 32,

the fine white lines between the colors printed from the shallows and

the ink printed from the relief surfaces are created by printing pressure

that was insufficient to force the paper onto  the

escarpments between the etched valleys and the relief plateaus of the

copperplate. Thus, the paper could not pick up any ink or color from

those bordering escarpments. We see precisely the same effect in monochrome,

ink-only prints, which no one doubts were printed in one pull, such

as Europe copy H plates 1 and 4 (illus. 34a, 35). In these impressions,

the inking dabber accidentally inked the

escarpments between the etched valleys and the relief plateaus of the

copperplate. Thus, the paper could not pick up any ink or color from

those bordering escarpments. We see precisely the same effect in monochrome,

ink-only prints, which no one doubts were printed in one pull, such

as Europe copy H plates 1 and 4 (illus. 34a, 35). In these impressions,

the inking dabber accidentally inked  the

shallows along with the relief areas, and both were printed simultaneously.

The fine white lines between relief and recessed areas were created

either by the dabber not depositing any ink on the escarpments or by

the paper not creasing at an angle sharp enough to pick up any ink from

those escarpments, in spite of relatively heavy printing pressure. The

effect in plate 1 of Europe copy H (illus. 34a) become clearly

evident when compared with an impression of the same plate which lacks

the accidental deposits of ink in the etched shallows (illus. 34b). the

shallows along with the relief areas, and both were printed simultaneously.

The fine white lines between relief and recessed areas were created

either by the dabber not depositing any ink on the escarpments or by

the paper not creasing at an angle sharp enough to pick up any ink from

those escarpments, in spite of relatively heavy printing pressure. The

effect in plate 1 of Europe copy H (illus. 34a) become clearly

evident when compared with an impression of the same plate which lacks

the accidental deposits of ink in the etched shallows (illus. 34b).

The white line in the branches of plate 1 of The Book of Urizen

copy D is most telling (illus. 36) ;

here we can actually see Blake painting the plate, applying his

green color on the inked relief lines and the green spilling

over and touching the shallows on both sides of the line, creating

white spaces between color and branches. If plates with colors from

the shallows were printed twice, then the white line would be uniformly

intersected with color. These white lines could not be perfectly aligned,

even if registration of the plate was absolutely perfect, because the

dampened paper, as Hayter and others have pointed out, would have minutely

changed its shape while being passed through the press, even if printed

with light pressure. This makes perfect registration of the white-line

escarpments of the second pull impossible—and detection under magnification

or computer enhancement possible. ;

here we can actually see Blake painting the plate, applying his

green color on the inked relief lines and the green spilling

over and touching the shallows on both sides of the line, creating

white spaces between color and branches. If plates with colors from

the shallows were printed twice, then the white line would be uniformly

intersected with color. These white lines could not be perfectly aligned,

even if registration of the plate was absolutely perfect, because the

dampened paper, as Hayter and others have pointed out, would have minutely

changed its shape while being passed through the press, even if printed

with light pressure. This makes perfect registration of the white-line

escarpments of the second pull impossible—and detection under magnification

or computer enhancement possible.

Accidental flaws in one-pull printing can be mistaken as evidence of two-pull printing. That such accidentals appear in Blake’s monochrome

impressions, unquestionably printed only

of two-pull printing. That such accidentals appear in Blake’s monochrome

impressions, unquestionably printed only once, should be sufficient warning against misinterpreting their mode

of production. For example, the droplets of color in the margins of

plate 24 in The Book of Urizen copies C and F (illus. 37-38),

which may lead one to suspect the edge of a second plate, is an effect

also present in monochrome impressions, such as America copy

H plate 10 and Europe copy H plate 1 (illus. 39-40) that were

assuredly printed just once. One-pull prints can even exhibit the slight

fuzziness, so typical of multi-plate and multi-pull printing, at the

margins between printed and unprinted surfaces because of slippage between

paper and plate

once, should be sufficient warning against misinterpreting their mode

of production. For example, the droplets of color in the margins of

plate 24 in The Book of Urizen copies C and F (illus. 37-38),

which may lead one to suspect the edge of a second plate, is an effect

also present in monochrome impressions, such as America copy

H plate 10 and Europe copy H plate 1 (illus. 39-40) that were

assuredly printed just once. One-pull prints can even exhibit the slight

fuzziness, so typical of multi-plate and multi-pull printing, at the

margins between printed and unprinted surfaces because of slippage between

paper and plate when run through

when run through  the

press. Color printing, particularly when done from the shallows as well

as the relief areas, multiplies the chances for accidental deposits

of ink and colors that do not contribute to the printed image, calligraphic

or pictorial. Thus it should be no surprise that Blake’s color prints

show, on average, more accidental effects than monochrome impressions. the

press. Color printing, particularly when done from the shallows as well

as the relief areas, multiplies the chances for accidental deposits

of ink and colors that do not contribute to the printed image, calligraphic

or pictorial. Thus it should be no surprise that Blake’s color prints

show, on average, more accidental effects than monochrome impressions.

|