|

|

| 5: THE ARGUMENTS FOR AND AGAINST TWO-PULL PRINTING |

|

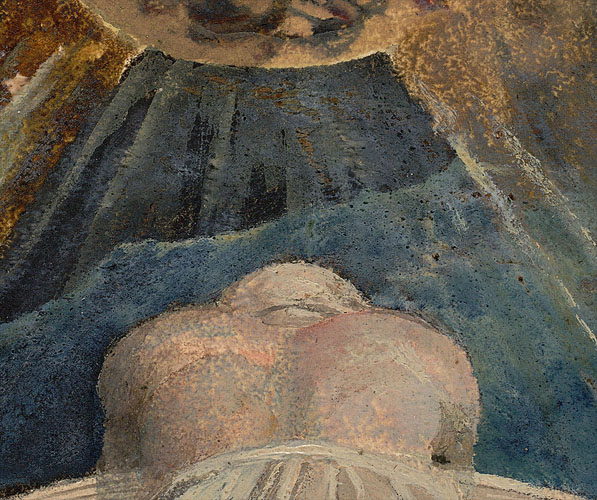

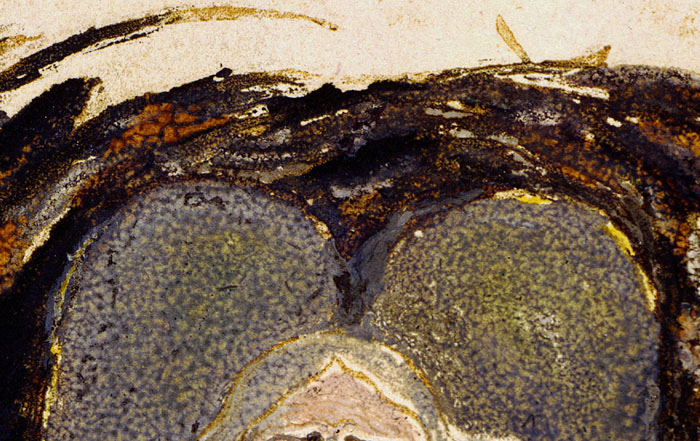

Colors applied to Phillips is right about the color over the date indicating a second stage in the production of the impression, but that second stage did not involve printing the color in a second pull. Had Blake done that, the wet colors would have mixed with the wet ink. Rather, the color was applied over the date when the impression was being finished in watercolors and pen and ink. These overlying colors have much smoother textures than the reticulated surfaces of printed colors. Further, if the colors had been printed over the date when the inked numbers were still wet, they would have mixed with the colors and become streaked or fuzzy, or even dissolved completely into the overlying colors. But, as Phillips' ultra-violet photograph of the impression (his color plate 50) reveals, the underlying numbers are clear and crisp. The colors must have been applied over the date when the ink was dry—and the ink would not have been dry if the overlying colors had been printed immediately after the first pull as part of a two-pull printing process. The evidence that the color over the date was applied as part of

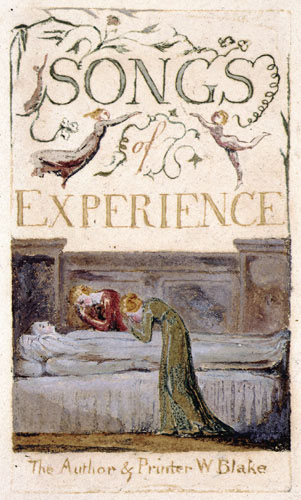

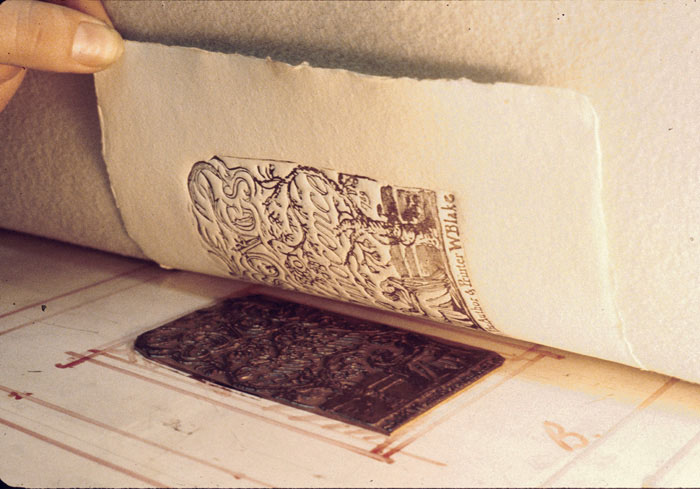

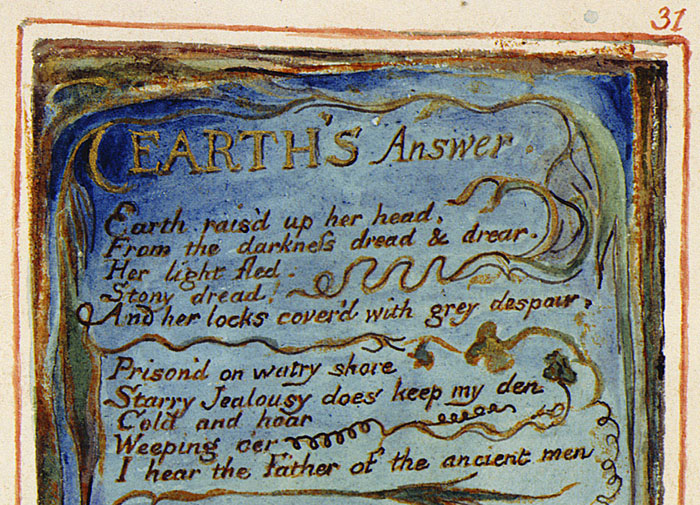

the finishing, Phillips’ second piece of positive evidence is his claim that there is a single tiny hole in the paper of the title page, “Introduction,” “Earth’s Answer,” and “London” from the Experience section of Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy T1. These four impressions are now in the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. He states (98) that “in all four copies [meaning “prints"] there is a pinhole in the upper left corner just outside of the plate image (plates 49 & 66 [his reproductions of title plate and “London”]).” According to Phillips, “this reveals that Blake used the traditional method of registration for printing a single sheet from more than one plate, but that he adapted the technique so that he could print twice from the same plate” (98). This claim, and the hypothesis that it indicates two-pull printing, is based on the use of pinholes in multiple-plate color printing (illus. 10, 13), in which the same-size plates were given pinholes, drilled into the copperplates, in the same positions in each plate. Printing from the first plate indents the holes into the paper; the printer pricks the holes with pins and aligns the paper to these holes when printing from the other plates. (Alternatively, the printer may use such a sheet of paper as a key to prepare a stack of damp paper with corresponding holes just before printing.) Registering paper to plates using this method requires at least two pinholes (Hayter 57), usually top and bottom, though four, one in each corner, appears to have been the norm in the eighteenth century. Because the sheet of paper blocks sight of the plate, this type of registration is done by touch, i.e., a pin through the paper engages the corresponding hole in the plate; the other pins feel for their holes, and when the paper is in position, the paper can be dropped into place (Hayter 58). The holes Phillips claims he found were one per plate, each near the top left corner of the plate. When we first learned about Phillips’ claims about pinholes, we were

immediately dubious for reasons we will discuss below. When we viewed

the Songs of Experience title page from copy T1,

displayed in a shallow glass-covered case at the Tate Britain exhibition

(number 117c in the catalogue), we could not, from just a few inches

from the print, perceive any pinhole. What There is no physical evidence that Blake ever experimented with the pinhole method of registration. If the marks at the top left corners of the Ottawa plates were made purposefully (as seems likely, given their presence on so many plates), they could not have had anything to do with registration since they could not have been visible when the paper was placed, face down, onto the copperplates. These marks were very probably made by someone other than Blake after the impressions left his hands. Indeed, they were probably made after the Ottawa plates were detached, as a separate and autonomous group (Bentley, Books 421), from the other T1 and T2 impressions, none of which shows any of the ink dots at issue. If Phillips could not re-visit Ottawa to confirm the presence of

pinholes, Theoretical superstructures rarely collapse even when their material

bases evaporate. It is certainly possible that someone somewhere someday

will find an impression of one of Blake’s illuminated books with

a tiny hole in the paper. We wish to dissuade researchers of a future

age from leaping to the conclusion that such a hole has something to

do with registering plate to paper during printing. The reasons for

rejecting even the possibility that Blake used single-pinhole registration

extend well beyond the mere absence of physical evidence of actual holes. Phillips does not explain why his supposed pinholes are outside the

edge of the plate (the “traditional method” called for the

holes to be in the metal itself), and suggests that Blake used a single

pin as an axis to “somehow” Besides the lack of practical utility if only one pin is used, it

is difficult to explain a circumstance in which only a single impression,

produced in a print run that included multiple impressions from each

plate, shows a pinhole. Blake printed x number of impressions from one

plate before moving to another plate in the same work. If pinholes were

made for the purpose of printing the plate twice upon the paper, then

the other impressions pulled from each plate in the same press run would

also have pinholes. Otherwise, we would be forced to assume that Blake

printed one impression with a pinhole, the others without, then moved

to a second plate using the pinhole method of registration for one impression,

but not for the others, and so on, moving back and forth between using

and not using pinholes. This would be an exceedingly inefficient printing

method. The assumption that any pinholes were made by Blake, let alone

for registration, stands on very shaky ground. Future discoverers of

tiny holes in Blake’s relief-etched prints, color printed or not,

must consider such holes in the context of the press-run in which the

impressions were created and in light of their subsequent histories

of ownership, sale, and rebinding. Phillips, in his discussion of the supposed pinholes in the Ottawa

prints, acknowledges the fact that there are no pinholes in any other

color-printed impressions. This absence inevitably forces him to conclude

that Blake abandoned the procedure, quickly moving on to find different

ways to register the plates. A printer can place on the bed of the press a sheet of paper cut

to exactly the same size as the sheet to be printed. Marks or lines

are then drawn on this “bottom sheet,” as it is generally

called, as guides to the placement (and later replacement) of the plate

on the bottom sheet. The sheet to be printed is then registered to the

four sides of the bottom sheet, thereby replicating the registration

of plate to bottom sheet. This procedure is repeated before each pull

through the press; registration is assured as long as the plate is placed

in its proper position on the bottom sheet and all sheets to be printed

are the same size as the bottom sheet. The use of a bottom sheet is

indicated by correct registration, with evenly aligned margins between

the edges of the printed image and the edges of the paper. In the case

of series work—that is, printing a set of impressions from the same

plate (and all printing is to some degree series printing)—bottom-sheet

registration is indicated by the same sheet size and the same margins

among all members of the set. This is what we see in the facsimiles

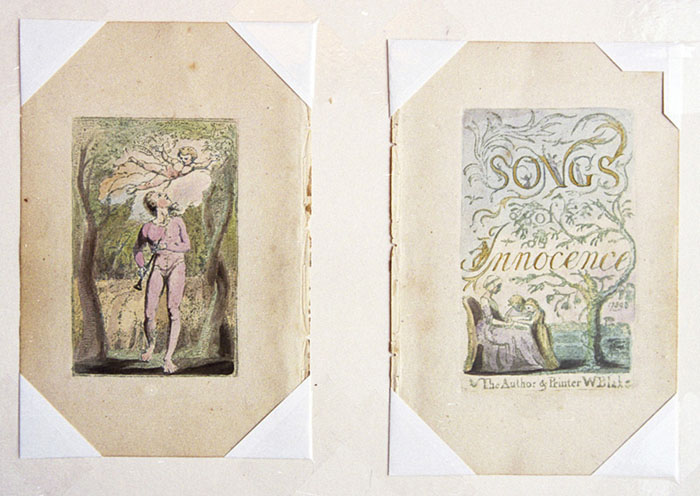

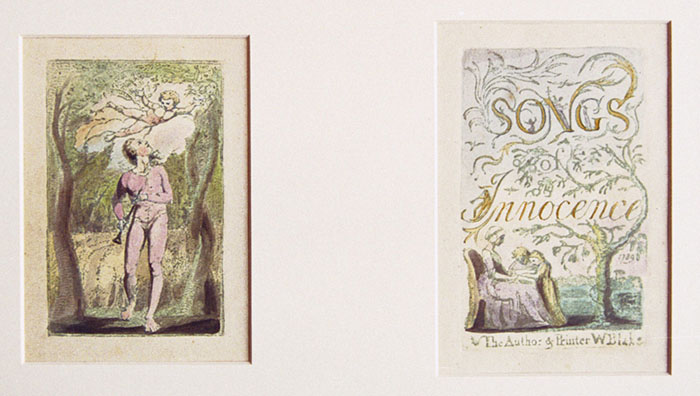

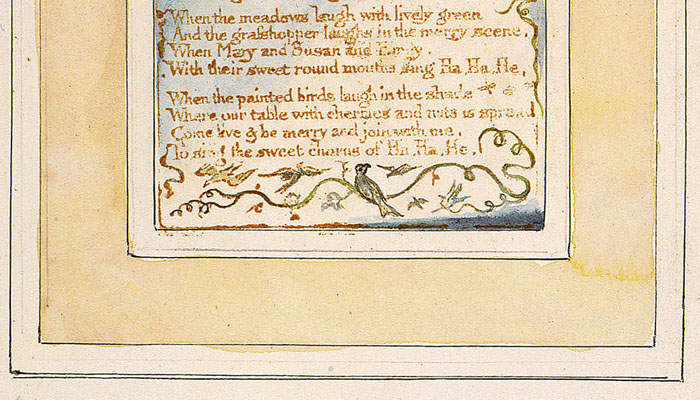

of sixteen plates from Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy

B printed by the Manchester Etching Workshop in 1983. Seventy-five impressions

But we never see any of these telltale characteristics of

bottom-sheet registration in Blake’s illuminated books. We find instead

images that are misaligned to the paper, with top Catherine and William Blake did not obsess over exact registration.

Indeed, in a deleted passage in his “Public Address,” Blake wrote that

“Spots & Blemishes” in works of art “are beauties & not faults”

(E 576). Nevertheless, the poor quality of Blake’s registration of plate

to paper no doubt comes as a surprise to most students of Blake. Publishers

of reproductions of the illuminated books generally straighten the plates

and usually trim to the image, because it is the image and not the artifact

that is being Phillips claims that Blake used bottom-sheet registration for all

his illuminated prints and not just the color prints (21). He acknowledges

that some images are misregistered, but finds most of these in “early

copies” and suggests that they evince the “constant attention” (21)

required to register plates to bottom sheets. The problems with these

observations are that the proportion of misaligned impressions can be

more than 50% of the prints in many copies of Blake’s illuminated books,

and that misaligned impressions appear in the vast majority of illuminated

books Blake printed, both early (as the 1789 and 1794 impressions above

demonstrate) and late. If Blake used bottom sheets to align his plates to his sheets of paper, then he was improbably sloppy either in making or following them. And if he knew that he was going to use bottom sheets, and going to adhere strictly to aesthetic and commercial conventions regarding image alignment, then why did he cut his sheets of copper to yield plates that were all different sizes and shapes? The plates of Songs of Innocence and of Experience, for example, vary from 11.0 x 6.3 cm. to 12.3 x 7.6 cm., and very few are perfect rectangles (i.e., with the same width at top, middle, and bottom, and same height at both sides). Engravers took great care to square their plates so the embossed platemark would be aesthetically pleasing, and publishers wanted uniform sized plates for their books for similar reasons. Fifteen of the plates Blake engraved for John Gabriel Stedman's Narrative, for example, vary only 4 mm. in width and height, which in turn made it easy for a printer to use a common bottom sheet for the print run. The fact that Blake’s copperplates are rarely perfect rectangles makes registration inherently difficult; even with careful registration, the uneven sides of the plates cannot be aligned with the edges of a rectangular sheet on all four sides. Nor can the plates be perfectly aligned to straight guide lines let alone to a shared bottom sheet. For instance, if all the different size plates were aligned to the same guide lines, then all the pages in the book would share at least one (top or bottom) identical margin at the expense of the other margins being overtly of different dimensions, but that is certainly not what we see in the illuminated books. Instead of fitting a series of plates to a uniform bottom sheet, Blake would have had to fit sheets per plate—that is, prepare custom-made bottom sheets. Such sheets would have been crucial in two-pull printing, because that actually involves four registrations (see below), which requires very precise guidelines and strict adherence to them. Given all of these easily observed characteristics of the illuminated books, Phillips’ proposals about bottom-sheet registration ask us to believe that Blake had difficulty with a kind of registration that did not require exact alignment, the purpose being to position properly the plate on its sheet of paper (illus. 49), but could execute the enormously more difficult registration required of two-pull printing over 650 times with only one mistake. A closer look at the use of bottom sheets is in order. The plate

in illustration 62 It seems highly improbable that there would be no other poorly registered impressions in color-printed illuminated books, other than the print of “Nurses song” previously discussed. As noted, Phillips’ theory asks us to believe that Blake was amazingly skilled in registering each plate twice, to yield over 650 perfectly aligned impressions, something Le Blon, Jackson, and other commercial printers set up for multiple plate work could not do—and to reconcile this with the clearly observable fact that Blake was carelessly inexact in the registration of plate to paper. The two-pull hypothesis generates these kinds of inherent contradictions when considered in light of Blake’s characteristic practices as printer and artist, and, as we will see, when seen in the light of Blake’s theories of art. Because the plates of an illuminated book are not uniform in size,

and because the sheets of paper they are printed on are not exactly

the same size, Blake could not have used the same bottom registration

sheet for all plates in the same book. Could Blake have used a different,

custom-made bottom sheet for each plate, or sheets with guide lines

to accommodate various sizes of plates? No, for the reasons given above:

their presence would be revealed in better alignment of plate to paper

than we find in Blake’s work, and this more exacting alignment would

be replicated in all other impressions pulled from the plate in the

same press run. Even if we abandon the idea that Blake printed multiple

impressions from each plate and assume for the sake of argument that

he printed only one impression before moving on to another plate, we

would still expect sheets that were aligned to bottom sheets to have

images registered more precisely to the printed sheet than we can observe

throughout the illuminated books. We would also have to explain the

waste of a great deal of paper to create many bottom sheets. And we

would be forced to embrace the now-discredited theory that Blake produced

his books per-copy rather than per-plate, one at a time rather than

in small groups, and embrace also all the economic and practical inefficiencies

that entails. While in principle registering paper and plate to a bottom

sheet appears to work well for the production of one impression, the

procedure becomes hopelessly complicated in practice when any one plate

is printed more than once, when it is part of a series, and when numerous

impressions are pulled from it. The technique breaks down by its own

clumsiness and inefficiencies that produce no aesthetic gain. If ignoring the evidence that Blake printed per-plate rather than per-book is not reasonable, then is it reasonable to suggest that Blake used a bottom sheet exclusively for color printing? Putting aside the thorny issue of Blake abandoning his direct mode of printing for a highly mechanical one for two or three years, the answer is still no. The same features noted above—impressions poorly registered to sheet edges and no shared margins within a book or among impressions from the same plate/bottom sheet—are true of color prints. The presence of diverse margins among pages in the same book, as

well as in impressions from the same plate in the same printing session,

reveals that Blake did not waste paper for bottom sheets but instead

“eyeballed” the paper to the plate, which is still a common practice

today. Phillips speculates that Blake could have used the roller of the press to pin the sheet of paper down, holding it in place, while the plate was removed, worked on, and returned to its place, which could have been indicated either on a bottom sheet or by two metal weights forming a corner where the plate was placed. According to Hayter, who used this method in his Atelier 17, the “position of the plate was marked with great precision on the bed of the press” and a “longer than usual . . . sheet of paper” was required. Nevertheless, like other registration methods, this one was not absolutely precise, because “after only one pass through the press, the paper has become stretched in length, and even when dry will never return exactly to the length it once had; then again, owing to the slight displacement of the blankets as the roller passes over the thickness of the plate, the register cannot in theory be guaranteed to less than one-half of this thickness” (58). Blake would have encountered other problems with this method. The

circumference of the upper wooden roller of the eighteenth-century press

that was displayed at the Blake exhibition at Tate Britain as an example

of the kind he most likely used is 71.4 cm. Holding the sheet in place with a metal weight and indicating the plate’s position by two weights forming a corner is equally inexact, particularly for small sheets of paper and small plates. This technique is more suitable for large plates, the size of America or larger, where a 1 mm. misregistration is less noticeable since it is a smaller percentage of the whole. With a small plate, even a slight misregistration is noticeable. |

| 0: SUGGESTIONS

FOR READERS FOR OPTIMAL VIEWING 1: INTRODUCTION 2: BACKGROUND & CONTEXT 3: BLAKE'S COLOR PRINTING METHODS 4: THE TWO-PULL THEORY 5: THE ARGUMENTS FOR AND AGAINST TWO-PULL PRINTING 6: WHY "NURSES SONG" WAS PRINTED TWICE 7: OCCAM'S RAZOR 8: POSTSCRIPT: SOME IMPLICATIONS 9: NOTES 10: LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 11: WORKS CITED |