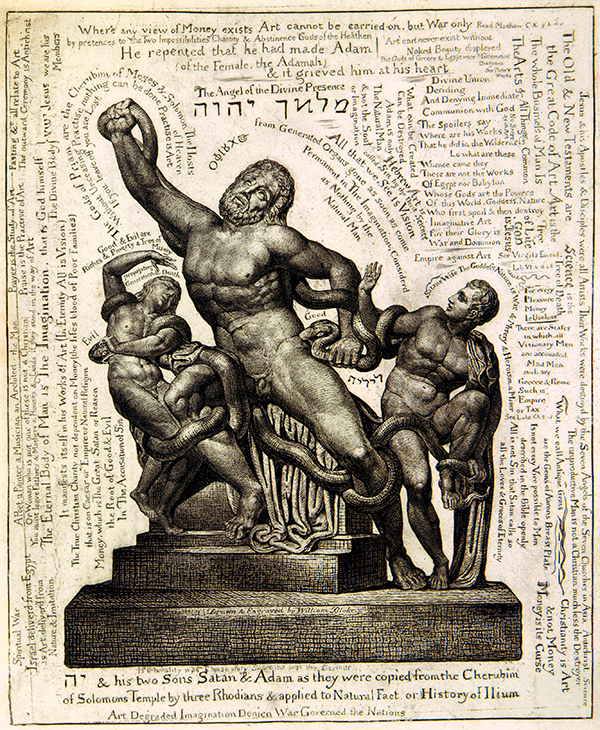

The Notebook, Laocoön, and Blake’s Beauties of Inflection

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.47761/biq.328Abstract

Though included among the articles of his “genius” from the start (see Dorfman 3-4), William Blake’s Notebook has received little scholarly treatment beyond the instrumental. It has functioned, for thematic readers, as another store of revealing epigrams; for editors, as a manuscript source for the Public Address and The Everlasting Gospel; for biographers, as a heartwarming keepsake from an intimate companion. In such cases the Notebook is used to subsidize some offshore critical enterprise at the expense of its own discursive and material integrity. To be sure, a handful of important Blakeans—Keynes, Jugaku, Bentley, Erdman—have outstripped instrumentality and, in a short series of facsimile editions and bibliographic studies, tended to the Notebook per se. With transcription and description, collation and chronology, these efforts march toward a fuller and more faithful representation of the Notebook as a literary- and art-historical artifact. But by design they stop short of the explanatory work of poetics—that is, the disclosure of “the conditions of meaning” and the other “means by which literary works create their effects” (Culler, Structuralist Poetics vii, xiv). It remains to be asked how the Notebook operates when subject to a thorough formal reading, and how, if at all, that operation might affect our understanding of Blake more generally.